“We had scarcely taken a dozen steps before we were greeted with a shower of round shot and shell from the enemy’s artillery. A round shot struck the ground fairly in front of me, covering me with sand, bounding to the right and killing the third man in the company to my right. It was followed by a shell, that gave us another shower of sand, and flew between the legs of Corporal Keefer, the man on my left, tearing his pantaloons, striking his file coverer, Billington, on the knee, and glancing and striking a man named Gensemer on Billington’s left, and bringing them to the ground, but fortunately failing to explode.”

— Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin, describing the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina in 1862

Formative Years

Born in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania in 1841, Samuel Hunter Billington was a son of Pennsylvania natives Maria (Gobin) Billington (circa 1817-1890; alternate spelling: “Mariah”) and Thomas A. Billington (circa 1818-1856), who was elected to serve as sheriff of Northumberland County during the mid-1840s. According to a letter from “Many of Shamokin” who submitted a letter to the editors of The Sunbury Gazette, for publication in an April 1845 edition of their newspaper, Thomas A. Billington was ” a very suitable man for the office of Sheriff.”

Mr. B is both farmer and mechanic; he is an honest, upright, plain, straight-forward man of excellent moral character and business habits, — active and industrious, and withal a sound and unflinching democrat of the Jeffersonian school.

His nomination and election would ensure, to our county, an able and efficient officer, and one who would do justice to all with whom he might have business. From these considerations we strongly urge his claims on the democracy of old Northumberland county, as a man well worthy of their united suffrages.

In 1850, Samuel Billington resided in the Borough of Sunbury in Northumberland County with his parents and sister, Louisa J. Billington (1850-1863), who was just one month old when a federal census enumerator arrived on the Billington family’s doorstep in mid-August of that year. Sadly, their happy lives would be changed forever when their family’s patriarch, Thomas A. Billington, fell ill with consumption (tuberculosis) and died in Sunbury less than six years later, on 10 March 1856. He was still in his late thirties or early forties at the time of his passing.

Still living in Sunbury at the time of the 1860 federal census, Samuel Billington continued to reside there with his mother and sister, Louisa, who was attending her local public school. Known to family and friends as “Hunter,” Samuel helped to support his family on the wages of a laborer, but they were not destitute. According to that year’s census enumerator, his mother owned real estate and personal property that was valued at one thousand and one hundred dollars (the equivalent of roughly forty-three thousand U.S. dollars in 2025).

That decade would prove to be an even more transformative one, however, as a secession crisis swept the United States of America into a full-blown civil war.

American Civil War

A member of his local militia unit, the Sunbury Guards, during the early 1860s, Samuel Billington was already a soldier-in-training at the dawn of the American Civil War. Even so, he was initially sidelined during the opening months of the war, forced to watch as seventy-eight of his fellow Sunbury Guardsmen and other friends and neighbors headed off to “end the rebellion” by the southern states that had seceded from the nation. But when those same Sunbury Guardsmen returned during that fateful summer of 1861 (upon expiration of their initial three-month terms of service) and decided to re-enlist for additional tours of duty, he was deemed ready to serve by his militia unit and was permitted to enroll alongside his more seasoned brethren.

Following his enrollment at the court house in Sunbury on 17 September 1861, nineteen-year-old Samuel H. Billington readied himself for transport south and was taken by train to Washington, D.C. He then made his way to where he would be stationed — at Camp Griffin near Langley, Virginia with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. On 31 October of that same year, he was officially mustered as a private with that regiment’s C Company, which was largely composed of members of his militia unit, the “Sunbury Guards.”

Military records at the time described Private Billington as a railroader who was six feet, five inches tall with black hair, gray eyes and a florid complexion.

In his letter of 13 October, Henry Wharton, a field musician with the 47th Pennsylvania’s C Company, described their duties, as well as their new home:

The location of our camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets….

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort, (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually….

In his letter of 17 November, Henry Wharton revealed still more details about life at Camp Griffin:

This morning our brigade was out for inspection; arms, accoutrements [sic], clothing, knapsacks, etc, all were out through a thorough examination, and if I must say it myself, our company stood best, A No. 1, for cleanliness. We have a new commander to our Brigade, Brigadier General Brannen [sic], of the U.S. Army, and if looks are any criterion, I think he is a strict disciplinarian and one who will be as able to get his men out of danger as he is willing to lead them to battle….

The boys have plenty of work to do, such as piquet [sic] duty, standing guard, wood-chopping, police duty and day drill; but then they have the most substantial food; our rations consist of fresh beef (three times a week) pickled pork, pickled beef, smoked pork, fresh bread, daily, which is baked by our own bakers, the Quartermaster having procured portable ovens for that purpose, potatoes, split peas, beans, occasionally molasses and plenty of good coffee, so you see Uncle Sam supplies us plentifully….

A few nights ago our Company was out on piquet [sic]; it was a terrible night, raining very hard the whole night, and what made it worse, the boys had to stand well to their work and dare not leave to look for shelter. Some of them consider they are well paid for their exposure, as they captured two ancient muskets belonging to Secessia. One of them is of English manufacture, and the other has the Virginia militia mark on it. They are both in a dilapidated condition, but the boys hold them in high estimation as they are trophies from the enemy, and besides they were taken from the house of Mrs. Stewart, sister to the rebel Jackson who assassinated the lamented Ellsworth at Alexandria. The honorable lady, Mrs. Stewart, is now a prisoner at Washington and her house is the headquarters of the command of the piquets [sic]….

Since the success of the secret expedition, we have all kinds of rumors in camp. One is that our Brigade will be sent to the relief of Gen. Sherman, in South Carolina. The boys all desire it and the news in the ‘Press’ is correct, that a large force is to be sent there, I think their wish will be gratified….

On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review that was overseen by Colonel Tilghman Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

As a reward — and in preparation for bigger things to come, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan obtained brand new Springfield rifles for every member of the 47th Pennsylvania.

Sketch of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ winter quarters at Camp Griffin, near Langley, Virginia, by Second Lieutenant William H. Wyker, Company E, December 1861 (public domain).

In December 1861, the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Quartermaster James Van Dyke, who had been enjoying an approved furlough at home in Sunbury, Pennsylvania, procured “various articles of comfort, for the inner as well as the outer man,” according to the 21 December 1861 edition of the The Sunbury American. Upon his return to camp, many of the 47th Pennsylvanians of German heritage were pleasantly surprised to learn that their city’s former sheriff had thoughtfully brought a sizable supply of sauerkraut with him. The German equivalent of “comfort food,” this favored treat warmed stomachs and lifted more than a few spirits that first cold winter away from loved ones.

Also that same winter, “the ladies of Sunbury” donated multiple blankets and clothing items to Union Army regiments to make the holidays a bit more pleasant for the boys in blue from Sunbury. Among those sending care packages were Private Samuel Billington’s mother, Maria Billington, who donated “a blanket, a pair of socks, and a pair of mittens,” and Mrs. Hugh Bellas, Lizzie Haas and Louisa Youngman, who each donated one blanket.

1862

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were transported to Florida aboard the steamship Oriental in January 1862 (public domain).

In response to orders from senior Union Army leaders to head for Maryland, Private Samuel Billington and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers departed from Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862. Marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church, they were then transported by rail to Alexandria, Virginia, where they boarded the steamship City of Richmond. Transported via the Potomac River to the Washington Arsenal, they were reequipped before they were marched off for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington, D.C.

The next afternoon, they hopped aboard cars on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland. Arriving around 10 p.m., they were assigned quarters in barracks at the United States Naval Academy. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship Oriental.

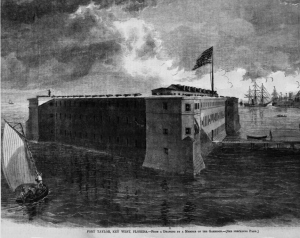

Ferried to the Oriental by smaller steamers during the afternoon of 27 January 1862, the enlisted members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry commenced boarding the big steamship, followed by their officers. Then, per the directive of Brigadier-General Brannan, the Oriental steamed away for the Deep South at 4 p.m. and headed for Florida which, despite its secession from the Union, remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Key West and the Dry Tortugas.

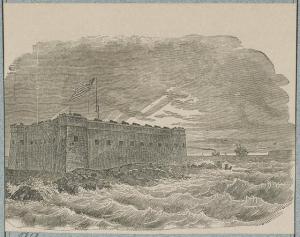

Woodcut depicting the harsh climate at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida during the American Civil War (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Private Billington and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers subsequently arrived in Key West, Florida In early February 1862, where they were assigned to garrison Fort Taylor. During the weekend of Friday, 14 February, the regiment introduced itself to Key West residents as it paraded through the streets of the city. That Sunday, a number of the men from the regiment mingled with local residents at area church services.

Drilling daily in heavy artillery tactics and other military strategies, they felled trees, built new roads and helped to strengthen the facility’s fortifications. But there were lighter moments as well.

According to a letter penned by Henry Wharton on 27 February 1862, the regiment commemorated the birthday of former U.S. President George Washington with a parade, a special ceremony involving the reading of Washington’s farewell address to the nation (first delivered in 1796), the firing of cannon at the fort, and a sack race and other games on 22 February. The festivities resumed two days later when the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Band hosted an officers’ ball at which “all parties enjoyed themselves, for three o’clock of the morning sounded on their ears before any motion was made to move homewards.” This was then followed by a concert by the Regimental Band on Wednesday evening, 26 February.

As the 47th Pennsylvanians soldiered on, many were realizing that they were operating in an environment that was far more challenging than what they had experienced to date — and in an area where the water quality was frequently poor. That meant that disease would now be their constant companion — an unseen foe that would continue to claim the lives of multiple members of the regiment during this phase of duty — if they weren’t careful.

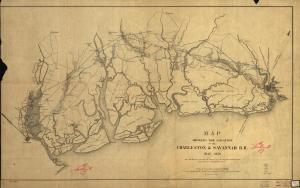

This 1856 map of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad shows the island of Hilton Head, South Carolina in relation to the towns of Beaufort and Pocotaligo (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Next ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina from mid-June through July, the 47th Pennsylvanians camped near Fort Walker before relocating to the Beaufort District, Department of the South, roughly thirty-five miles away. Frequently assigned to hazardous picket detail north of their main camp, which put them at increased risk from enemy sniper fire, the members of the 47th Pennsylvania became known for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing,” and “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan,” according to historian Samuel P. Bates.

Detachments from the regiment were also assigned to the Expedition to Fenwick Island (9 July) and the Demonstration against Pocotaligo (10 July), while men from Companies B and H “crossed the Coosaw River at the Port Royal Ferry and drove off the Rebel pickets before returning ‘home’ without a loss,” according to Schmidt. The actions were the Union’s response to the burning by Confederate troops of the ferry house at Port Royal.

Saint John’s Bluff and the Capture of a Confederate Steamer

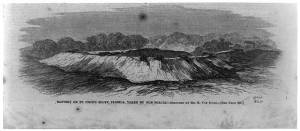

Earthworks surrounding the Confederate battery atop Saint John’s Bluff along the Saint John’s River in Florida (J. H. Schell, 1862, public domain).

During a return expedition to Florida beginning 30 September, members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined with members of the 1st Connecticut Battery, 7th Connecticut Infantry, and part of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry in assaulting Confederate forces at their heavily protected camp at Saint John’s Bluff, overlooking the Saint John’s River area. Trekking and skirmishing through roughly twenty-five miles of dense swampland and forests after disembarking from ships at Mayport Mills on 1 October, they subsequently captured artillery and ammunition stores (on 3 October) that had been abandoned by Confederate forces during a bombardment of the bluff by Union gunboats.

According to Henry Wharton, “On the day following our occupation of these works the guns were dismounted and removed on board the steamer Neptune, together with the shot and shell, and removed to Hilton Head. The powder was all used in destroying the batteries.”

Meanwhile that same weekend (Friday and Saturday, 3-4 October 1862), Brigadier-General Brannan, who was quartered on board the Ben Deford as the Union expedition’s commanding officer, was busy penning reports to his superiors while also planning the next move of his expeditionary force. That Saturday, Brannan chose several officers to direct their subordinates to prepare rations and ammunition for a new foray that would take them roughly twenty miles upriver to Jacksonville. (A sophisticated hub of cultural and commercial activities with a racially diverse population of more than two thousand residents, the city had repeatedly changed hands between the Union and Confederacy until its occupation by Union forces on 12 March 1862.) Among the Union soldiers selected for this mission were 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers from Company C, Company E and Company K.

Boarding the Union gunboat Darlington (formerly a Confederate steamer), they moved upriver, along the Saint John’s, with protection from the Union gunboat Hale, ultimately traveling a distance of two hundred miles. Charged with locating and capturing Confederate ships that had been engaged in furnishing troops, ammunition and other supplies to Confederate Army units scattered throughout the region, including the batteries at Saint John’s Bluff and Yellow Bluff, they played a key role in capturing the Governor Milton, a Confederate steamer that was docked near Hawkinsville.

Integration of the Regiment

The 47th Pennsylvania also made history during the month of October 1862 as it became an integrated regiment, adding to its muster rolls several Black men who had escaped chattel enslavement from plantations near Beaufort, South Carolina. Among the formerly enslaved men who enlisted at this time were Bristor Gethers, Abraham Jassum and Edward Jassum.

Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina

Highlighted version of the U.S. Army map of the Coosawhatchie-Pocotaligo Expedition, 22 October 1862 (public domain).

From 21-23 October 1862, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers joined with other Union troops in engaging heavily protected Confederate forces in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina, including at the Frampton Plantation and the Pocotaligo Bridge, a key piece of railroad infrastructure that senior Union military leaders felt should be eliminated.

Harried by snipers while en route to destroy the bridge, they also met resistance from Confederate artillerymen who opened fire as they entered an open cotton field.

Those headed toward higher ground at the Frampton Plantation fared no better as they encountered rifle and cannon fire from the surrounding forests. But the Union soldiers would not give in. Grappling with Rebel troops wherever they found them, they pursued them for four miles as the Confederate Army retreated to the bridge. Once there, the 47th Pennsylvania relieved the 7th Connecticut.

The engagement proved to be a costly one for the 47th Pennsylvania, however, with multiple members of the regiment killed instantly or so grievously wounded that they died the next day or within weeks of the battle. Among those killed in action was Captain Charles Mickley of Company G; one of the mortally wounded was K Company Captain George Junker.

The U.S. Army’s General Hospital on Hilton Head Island in South Carolina, shown here circa 1861-1865, was built facing the ocean and Port Royal Bay at the mouth of the Broad River (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain; click to enlarge).

One of the “less seriously” wounded was Private Samuel H. Billington, whose right knee had been fractured by an artillery shell — an injury severe enough that it would be documented in a federal government census nearly thirty years later. Transported back to South Carolina by one of the Union Army troop carriers, he received medical care from Union Army surgeons at the Union Army’s general hospital on Hilton Head Island.

In a letter penned to friends back home in Sunbury on 27 October 1862, C Company Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin provided detailes about the Battle of Pocotaligo and about members of his company who had been killed or wounded, including Private Samuel Billington:

For the first time since our terrible engagement on the main land, I find time to write you an account of the affair…. On Tuesday morning [21 October 1862] our regiment received orders for six hundred men to embark on a Transport, with two days’ rations, at 1 o’clock P.M. I selected sixty men, and embarked. Our destination was unknown, although it was the general opinion that it was the Charleston and Savannah Railroad bridges. We steamed down the river, and were all advised by. Gen. Brannan, who was on the boot with our regiment, to get as much sleep as possible. I sought my berth, and when I awoke next morning, found we were in the Broad River, opposite Mackay’s Point. A detachment of the 4th New Hampshire, sent on shore to capture the enemy’s pickets, having failed, we were ordered to disembark immediately. Eight Companies of our regiment, (the other two being on another Transport) were gotten [illegible word], and at once took up the line of march. After about three miles, we came in sight of the pickets, when we halted until joined by the 55th Pennsylvania, 6th Connecticut, and one section of the 1st U.S. Artillery. We were again ordered forward — a few of the enemy’s cavalry slowly retiring before us, until we reached a place known as Caston, where two pieces of artillery, supported by cavalry, were discovered in position in the road. — They fired two shells at us, which went wide. While our artillery ran to the front and unlimbered, our regiment was ordered forward at double quick. The enemy however left after receiving one round from our artillery, which killed one of their men. We followed them closely for about two miles, when we found their battery of six pieces, posted in a strong position at the edge of a wood, supported by infantry and cavalry.

They opened upon us immediately, which was replied to by our artillery, posted in the road. This road ran through a sweet potato field, covered with vines and brush. Our regiment was thrown in mass and deployed on my company [Company C, the flag-bearer unit], which brought my right in the road. We were ordered to charge, and with a yell the men went in. We had scarcely taken a dozen steps before we were greeted with a shower of round shot and shell from the enemy’s artillery. A round shot struck the ground fairly in front of me, covering me with sand, bounding to the right and killing the third man in the company to my right. It was followed by a shell, that gave us another shower of sand, and flew between the legs of Corporal Keefer, the man on my left, tearing his pantaloons, striking his file coverer, Billington, on the knee, and glancing and striking a man named Gensemer on Billington’s left, and bringing them to the ground, but fortunately failing to explode. Almost at the same instant Jeremiah Haas and Jno. Bartlow were struck, the former in the face and breast by a piece of shell, the latter through the leg by a cannister shot. The shower we received here was terrific. Nothing daunted, on they rushed for the battery, but it was almost impossible to get through the weeds and vines. When within a hundred yards the enemy limbered up, and retreated through the woods. We followed as rapidly as possible, but we had scarcely entered the woods, when we were again greeted with a terrific storm of shell, grape and cannister from a new position, on the other side of the woods.

Ordering my men to keep to the right of the road, we pushed forward through a wood almost impenetrable. We were at times obliged to crawl on our hands and knees. — In the meantime the enemy’s infantry opened upon us, and assisted in raking the woods. Sergeant Haupt [Peter Haupt] here received his wound. When at length we pushed through, we found ourselves separated from the enemy by an impassable swamp, about one hundred yards in width. The only means of getting over was by a narrow causeway of about twelve feet in width. Seeing this, our regiment fell back to the edge of the woods, lay down and engaged the enemy’s infantry opposite us. In the meantime two howitzers from the Wabash, [which] had been placed in position in the rear of the woods, commenced shelling the enemy, whose artillery was on the right of the road on the opposite side of the swamp. The latter replied, the shells of both parties passing over us. Our situation here was extremely critical. Exposed to the cross-fire of the contending artillery and the infantry in the front, with the limbs and tops of trees falling on and around us, it was indeed a position I never want to be placed in again. — Here, Peter Wolf, while endeavoring in company with Sergeant Brosious, Corp S. Y. Haupt and Isaac Kembel, to pick off some artillerymen, received two balls and fell dead. I had him carried five miles and buried by the side of the road. Corporal S. Y. Haupt, had the stock of his rifle shattered by a rifle ball, that embedded itself.

In about twenty minutes the fire became too hot for them, and they again “skedaddled” just as Gen. Terry’s Brigade, 75th Pennsylvania in advance, were ordered up to relieve us. They followed them up rapidly until they arrived at Pocotaligo creek, over which the rebels crossed, and tore up the bridge, and ensconced themselves behind their breastworks and in their rifle pits. — We were again ordered forward, deployed to the right, and advanced to the bank of the creek, or marsh, which was fringed by woods. We lay a short time supporting the 7th Connecticut, when their ammunition became expended, and we took the front. Here occurred the most desperate fighting of the day. The enemy were reinforced by the 26th South Carolina, which came upon the breastworks with a rush. We gave them a volley that sent them staggering, but they formed in the rear of the first line, and the two poured into us one of the most scathing, withering fires ever endured. Added to it, their artillery commenced throwing grape and cannister amongst us, but we soon drove the artillerymen from their guns, and silenced them. The colors on the left of my company attracting a very heavy fire, I ordered the Sergeant to wrap them up. — This caused quite a yell among the Confederates, but we soon changed their tune. — We fired until our ammunition was nearly expended, when we ceased. This caused the enemy’s artillery to open upon us, while the musketry continued with redoubled energy. Eight men of my company fell at this last fight. We held our position, unsupported, until dark, when we were ordered to fall back. We did so and covered the retreat. We were the first regiment in the fight, and last out of it. Our men fought like veterans, and did fearful execution among the enemy. Our loss was very heavy, losing one hundred and twelve men out of six hundred. I detailed my entire company to carry their dead and wounded comrades to the boat, which I did not reach until 4 o’clock A.M., bringing with me the last man, Billington. In consequence of having no stretchers or ambulances, we were compelled to carry our wounded in blankets. They were, however, all taken good care of.

My men fought as men accustomed to it all their life. Nothing could exceed their valor. In addition to the loss in my own company, of the color guard, composed of Corporals from other companies attached to it, all but two were struck. Every man seemed determined to win.

My loss is as follows: — Killed — Peter Wolf, Sunbury, Pa.; George Harner, Upper Mahanoy; Seth Deibert, Lehigh county. — Wounded — Sergeant Peter Haupt, Sunbury, Pa., cannister shot through the foot, will save the foot; Corporal Samuel Y. Haupt, Sunbury, rifle shot on chin, will be ready for duty in a week. His rifle was struck with a piece of shell, and after shattered by rifle ball. Corporal William Finck, near Milton, rifle shot through leg — amputation not necessary; private S. H. Billington, Sunbury, struck on knee by shell, will save the leg; private John Bartlow, cannister shot through leg, will save the leg; private Jeremiah Haas, struck in face and breast by piece of shell, will soon be well; private Conrad Halman [sic, “Holman”], Juniata county, shot in face by rifle ball — teeth all gone, will recover; private Theodore Kiehl, Sunbury, struck in the mouth by a rifle ball, lower jaw shattered, but will recover; Charles Leffler [sic, “Lefler”], Lehigh county, rifle shot through leg — will recover without amputation; Michael Larkins [sic, “Larkin”], Lehigh county, wounded in side and hip in a hand to hand fight with a mounted officer, killed the officer and captured his horse, able to be about; Thomas Lotherd [sic, “Lothard”; alias of “Charles Marshall“], Pittston, Pa., grape shot through right side — will recover; Richard O’Rourke, Juniata county, rifle ball through right side — will recover; James R. Rine [sic, “Rhine”], Juniata county, struck on leg by round shot — not serious.

Captain Gobin then ended his letter by stating, “This being over one-fourth of the number engaged, I think is pretty heavy. However I think most of the wounded will be fit for duty again.”

They are all comfortable and well cared for. None of their wounds will, from present appearances, prove mortal.

In a follow-up letter penned to friends three weeks after the battle, Captain Gobin provided an update for his community regarding his C Company men who were either convalescing at the 47th Pennsylvania’s camp in Beaufort, South Carolina or were still hospitalized on Hilton Head Island:

…. I have not heard from Sergt. Haupt [sic, Peter Haupt] today. Yesterday he was still living and improving, and I now have hopes of his recovery. I was down on Saturday last and both nurses and doctor promised me to do everything in their power to save him. If money or attention can save him it must be done.

The rest of the wounded of my Company are doing very well. All will recover, I think, and lose no limbs, but how many will be unfit for service I cannot yet tell. Billington, Kiehl, Barlton [sic, “Bartlow“], Sergt. Haupt and Leffler [sic, “Lefler”] are yet at Hilton Head. Billington is on crutches and attending to Haupt or helping. Barlton [sic, “Bartlow”] and Leffler [sic, “Lefler”] are also on crutches. Kiehl is walking about, but his jaw is badly shattered. Corp. S. Y. Haupt is on duty. Haas’ wound is healing up nicely. Corp. Finck is about on crutches. O’Rourke, Holman, Lothard, Rine [sic, “Rhine”], and Larkins [sic, “Larkin”] are in camp, getting along finely. Those who were wounded in the body, face and legs all get along much better than Sergt. Haupt who was wounded in the foot. His jaws were tightly locked the last time I saw him.

The Yellow fever is pretty bad at the Head, and I do not like to send any body down. I am holding a Court Martial, and keep very busy. The fever creates no alarm whatever here. No cases at all have occurred save those brought from Hilton Head. We have had two frosts and all feel satisfied that will settle the fever. Some good men have fallen victims to it. Gen. Mitchell [sic, “Major-General Ormsby Mitchel”] is much regretted here.

Sixty of my men are on picket under Lieut. Oyster, [sic, “Daniel Oyster”], Lieut. Rees [sic, “William Reese”] having been on the sick list. However he is well again. The balance of the men are all getting along finely. Warren McEwen had been sick but is well again. My health is excellent. Spirits ditto. I suppose however by the looks of things I will be kept in Court Martials for a month longer, the trial list being very large. The men begin to look on me as a kind of executioner as it seems I must be upon every Court held in the Dep’t [Department of the South]….

The day after that letter was written by Captain Gobin, Sergeant Peter Haupt succumbed to “lockjaw” — a complication from the tetanus virus that he had contracted when cannister shot penetrated his foot during the Battle of Pocotaligo.

USS Seminole and USS Ellen accompanied by transports (left to right: Belvidere, McClellan, Boston, Delaware, and Cosmopolitan) at Wassau Sound, Georgia (circa January 1862, Harper’s Weekly, public domain).

Ordered back to Key West on 15 November 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers would spend the coming year guarding federal installations in Florida. Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I would once again garrison Fort Taylor in Key West, while the men from Companies D, F, H, and K would garrison Fort Jefferson, the Union’s remote outpost in the Dry Tortugas off the southern coast of Florida.

After packing their belongings at their Beaufort, South Carolina encampment and loading their equipment onto the U.S. Steamer Cosmopolitan, the officers and enlisted members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry sailed toward the mouth of the Broad River on 15 December 1862, and anchored briefly at Port Royal Harbor in order to allow the regiment’s medical director, Elisha W. Baily, M.D., Private Samuel Billington and other members of the regiment who had recuperated enough from their Pocotaligo-related battle injuries at the Union’s general hospital at Hilton Head to rejoin the regiment.

At 5 p.m. that same evening, the regiment sailed for Florida, during what was described by several members of the 47th as a treacherous and nerve-wracking voyage. According to historian Lewis Schmidt, the ship’s captain “steered a course along the coast of Florida for most of the voyage,” which made the voyage more precarious “because of all the reefs.” On 16 December, “the second night, the ship was jarred as it ran aground on one during a storm, but broke free, and finally steered a course further from shore, out in the Gulf Stream.”

In a letter penned to the Sunbury American on 21 December, Company C soldier Henry Wharton provided the following details about the regiment’s trip:

On the passage down, we ran along almost the whole coast of Florida. Rather all dangerous ground, and the reefs are no playthings. We were jarred considerably by running on one, and not liking the sensation our course was altered for the Gulf Stream. We had heavy sea all the time. I had often heard of ‘waves as big as a house,’ and thought it was a sailors yarn, but I have seen ’em and am perfectly satisfied; so now, not having a nautical turn of mind, I prefer our movements being done on terra firma, and leave old neptune to those who have more desire for his better acquaintance. A nearer chance of a shipwreck never took place than ours, and it was only through Providence that we were saved. The Cosmopolitan is a good riverboat, but to send her to sea, loadened [sic, loaded] with U.S. troops is a shame, and looks as though those in authority wish to get clear of soldiers in another way than that of battle. There was some sea sickness on our passage; several of the boys ‘casting up their accounts’ on the wrong side of the ledger.

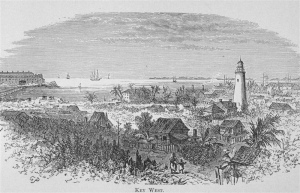

Lighthouse, Key West, Florida, early to mid-1800s (Florida for Tourists, Invalids, and Settlers, George M. Barbour, 1881, public domain).

According to Corporal George Nichols of Company E, “When we got to Key West the Steamer had Six foot of water in her hole [sic, hold]. Waves Mountain High and nothing but an old river Steamer. With Eleven hundred Men on I looked for her to go to the Bottom Every Minute.”

Although the Cosmopolitan arrived at Key West Harbor on Thursday, 18 December, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers did not set foot on Florida soil until noon the next day. The men from Companies C and I were immediately marched to Fort Taylor, while the men from Companies B and E were assigned to older barracks that had previously been erected by the U.S. Army. Members of Companies A and G were marched to the newer “Lighthouse Barracks” located on “Lighthouse Key.”

1863

Stationed in Florida for the entire year of 1863, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were literally ordered to “hold the fort.” Their primary duty was to prevent foreign powers from assisting the Confederate Army and Navy in gaining control over federal installations and other territories across the Deep South. In addition, the regiment was also called upon to play an ongoing role in weakening Florida’s ability to supply and transport food and troops throughout areas held by the Confederate States of America.

Prior to intervention by the Union Army and Navy, the owners of plantations, livestock ranches and fisheries, as well as the operators of smaller family farms across Florida, had been able to consistently furnish beef and pork, fish, fruits, and vegetables to Confederate troops stationed throughout the Deep South during the first year of the American Civil War. Large herds of cattle were raised near Fort Myers, for example, while orchard owners in the Saint John’s River area were actively engaged in cultivating sizeable orange groves. (Other types of citrus trees were found growing throughout more rural areas of the state.)

Florida was also a major producer of salt, which was used as a preservative for food. Consequently, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and other Union troops across Florida were ordered to capture or destroy salt manufacturing plants in order to further curtail the enemy’s access to food.

Tragically, as the winter season ebbed and Private Samuel Billington continued to convalesce far from home, he received heartbreaking news. His youngest sister, Louisa Billington, had died at the age of thirteen in Sunbury on 29 March 1863. Researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story have not yet identified her burial location, but have located this announcement of her death in The Sunbury Gazette:

In Sunbury, on March 29th, Louisa Billington, daughter of Mrs. Maria Billington, in the 13th year of her age.

Very few, whether young or old, are called to endure a greater amount of, or a longer season of physical suffering, and certainly none could have exercised more of patience and cheerfulness. She was chosen in the furnace of affliction, and made perfect through suffering. No murmuring accents escaped her lips, and now that it is well with her, who can doubt? In a little book of Scripture passages she marked these words: “Rejoice evermore.” So she did while suffering, and so she will, as forever she reigns with Jesus “the Lamb.”

Less than three months after his sister’s death, Private Billington was examined yet again again by one of the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental surgeons, who determined that the grieving man was still so debilitated by his knee wound that he should be sent home to recuperate. According to The Sunbury Gazette, “S. Hunter Billington … returned from Capt. Gobin’s Company at Key West, on account of ill-health” sometime prior to the publication of its 20 June 1863 edition. He had been transported north from the harbor in Key West, Florida by ship to either New York City or Philadelphia and then home to Sunbury by train.

Military records subsequently noted that he was officially honorably discharged from the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry on a surgeon’s certificate of disability on 1 July 1863.

Return to Civilian Life

The Central Hotel, Sunbury, Pennsylvania roughly five years after its 1865 sale by former 47th Pennsylvania Quartermaster James Van Dyke to Henry Haas (circa 1870, public domain).

Upon returning to Sunbury, Samuel Billington continued to adjust to life as a wounded warrior. On 13 January 1864, he wed New Jersey native Mary Eleanor Voute (1842-1890), who was a resident of Burlington in Burlington County in that state and a daughter of Edward and Charlotte Voute. Following their wedding at the Broad Street United Methodist Church in Burlington, Samuel Billington then settled with his new bride in Sunbury, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, where he subsequently announced that he was opening a bakery in March of that same year to “supply the citizens of this place with fresh bread, wheat and rye, every other day,” according to The Sunbury Gazette.

Samuel Billington and his wife then also welcomed the births of: Louisa I. Billington (1867-1943), who was born in that county on 6 October 1867 and never married; Thomas A. Billington (1869-1933), who was born on 27 April 1869 and later wed Laura M. Green (1875-1927); Margaret/Mary H. Billington, who was born circa 1870; Mariah G. Billington, who was born circa 1871; Anna Frances Billington (1873-1916), who was born in April 1873, was known to family and friends as “Fannie” and never married; Alice Billington (1877-unknown), who was born in March 1877 and later wed and was widowed by Harry Fetzer (1872-1954); Elizabeth H. Billington (1879-1962), who was born in July 1879 and later wed Raymond Benyard Llewellyn (1877-1958) in Camden, New Jersey on 23 March 1898; and Hiram L. Billington (1883-1936), who was born in Sunbury on 19 June 1883 and later wed Elsie May Ross (1880-1970) in 1910.

In 1870, Samuel Billington and his wife operated a boarding house in Sunbury. By 1880, he was employed as a laborer, and was residing at the home of his mother, Maria, at 256 Chestnut Street in the same borough. Also living with him were his wife, Mary, and their children: Louisa (aged fourteen), Thomas (aged twelve), Mary (aged ten), Mariah (aged nine), Anna (aged eight), Alice (aged six), and Elizabeth (aged one). All of Samuel’s children, except for his two youngest — Alice and Elizabeth — were students at their local public school. Still plagued by physical problems related to his battle wound, Samuel filed for a U.S. Civil War Pension in 1876, which was subsequently awarded to him.

In late June 1885, Samuel Billington’s mother, Maria Billington, and his wife, Mary Billington, traveled to Sunbury to visit with friends for several days.

One of many streets in the Borough of Milton, Pennsylvania impacted by the Great Flood of 1889 (photo taken circa 1 June 1889, public domain).

Tragedy then struck the Billingtons and other Pennsylvanians during the Great Flood and Storms of 1889. According to the U.S. National Weather Service:

On May 31, 1889, a catastrophic failure of the South Fork Dam on the Little Connemaugh River, approximately 14 miles upstream of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, resulted in one of the worst natural catastrophes in the history of the United States, creating the largest loss of life from a natural disaster not caused by a hurricane or earthquake.

Intense heavy rains fell across the area in the day preceding the failure, and the poorly maintained earthen dam weakened and subsequently failed during the afternoon hours. This sudden failure sent a torrent of water down a canyon, into the heart of Johnstown. It was reported that the flood wave produced a wall of water 35 feet high and a half mile wide….

Flooding was also widespread across the state from this weather event. Major flooding was reported along the West Branch of the Susquehanna River. The prosperous lumber town of Williamsport reported that 75 percent of the town was under water during the peak of the flooding.

According to the Johnstown Area Heritage Association, “The rain, which began in the late afternoon of Thursday, May 30, continued with increased violence until Saturday, June 1. Clearfield borough had flooded streets by 5 a.m., May 31…. Renovo, southeast of Clearfield on the West Branch, was flooded by evening, May 31.”

At 8 p.m. [on 31 May 1889], the West Branch [of the Susquehanna River] at Lock Haven began to rise rapidly…. The log dam held until 2 a.m., Saturday, June 1, when it broke with a great roar….

The West Branch was running seventeen feet deep at the time that the boom at Lock Haven broke. With the endless procession of the 73,000,000 million feet of lumber spanning the river, the flood bore down on Williamsport where another log boom crossed the river.

The flood entered Williamsport at 3 a.m., Saturday morning [1 June 1889].

That same day (1 June 1889), flood waters also spread through the streets, homes and businesses of multiple communities across Northumberland County, including the Borough of Milton, where members of the Billington family were living. The Northumberland County Democrat subsequently reported that “The flood cost Milton $300,000,” and that flood waters had “reached above the counters in nearly every store in Milton.”

Due to that devastation and the diseases that spread rapidly across the region as a result of the contaminated flood waters and flood debris, Samuel H. Billington moved his family to the city of Camden in Camden County, New Jersey sometime before June of 1890, as documented by a special veterans census that was conducted by the federal government that year. The change of scenery did not appear to help his wife, however, because she died in Camden on 11 July 1890. According to her funeral notice in The Sunbury News:

Mrs. S. H. Billington passed away Friday July 11 after a long siege of illness which was contracted in the Milton flood of last year. She leaves a husband and eight children to mourn her loss, six daughters, and two sons. The funeral was conducted Monday afternoon at two o’clock by the Rev. Mr. Loucke of the First Presbyterian Church of Camden.

Sadly, the Christmas holidays that year were made even more painful by the death of Samuel Billington’s mother, Maria (Gobin) Billington, who passed away at the age of seventy-three, at Samuel’s home in Camden on 15 December of that same year. Researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story have not yet identified her burial location.

Death and Interment

Less than three years after his wife’s passing, Samuel Hunter Billington died at the age of fifty-three at the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on 28 March 1893. Following funeral services, which were held at his home at 625 Grant Street in Camden, New Jersey at 2:30 p.m. on 30 March, his remains were returned by train to the Borough of Sunbury in Pennsylvania for burial at the Sunbury Cemetery.

What Happened to Samuel Billington’s Children?

Samuel Billington and his children lived in Camden, New Jersey during the final years of renowned American poet, Walt Whitman (1819-1892), who lived at this house on Mickle Street in Camden from 1884 until his death in 1892 (public domain).

Samuel Billington’s daughter, Fannie Billington, never married and continued to live in Camden after his death. According to the New Jersey state census of 1895, she resided in Camden’s Second Ward that year with her brother, Hiram Billington, and their sisters, Alice and Lizzie Billington. By June of 1905, she was living at the home of her brother, Thomas A.Billington, and his family on Pleasant Street in Camden’s Eleventh Ward. She died at the age of forty-two in Camden on 22 December 1916. Following funeral services at her brother’s home at 2001 River Avenue in Camden, she was laid to rest at that city’s Evergreen Cemetery on 26 December.

Following his marriage to Laura Green in Camden on 6 December 1890, Samuel Billington’s son, Thomas A. Billington, settled with her in Camden County, New Jersey, where they welcomed the births of: Mabel Billington (1892-1974), who was born on 15 July 1892 and later wed John Harvey Hanson (1892-1962); Myrtle Billington (1894-1968), who was born on 26 December 1894 (alternate birth years: 1892, 1895) and later wed Charles William Schoelkopf (1894-1983); and Edith Billington (1898-unknown), who was born on 5 March 1897 (alternate birth year: 1898) and later wed Robert Briggs. Employed as a foreman at a chemical factory after the turn of the century, Thomas A. Billington resided in Camden’s Tenth Ward with his wife and their three daughters. They then welcomed the Camden births of: Thomas Billington, Jr. (1900-1956), who was born on 8 November 1900; and Harold Roosevelt Billington (1903-1951), who was born on 7 August 1903. Predeceased by his wife in 1927, Thomas A. Billington died in his early to mid-sixties in Camden on 10 April 1933, and was laid to rsst at the Arlington Park Cemetery in Pennsauken, Camden County.

Samuel Billington’s son, Hiram L. Billington, resided with his sister, Lizzie (Billington) Llewellyn, and her family in Camden’s Second Ward after the turn of the century, and was employed as a printer. By 1910, he had secured employment as an iron worker with the Merrit Company and was residing at the boarding house of John Ross in Pennsauken Township, Camden County. Later that same year, he married John Ross’s daughter, Elsie Mae Ross (1880-1970). Together, they welcomed the births of: Earl Raymond Billington (1915-1975), who was born in Pennsauken Township on 15 October 1915 and later wed Matilda Jane Ridgway (1920-2001); and Ralph Larson Billington (1920-1978), who was born in Pennsauken Township on 7 October 1920 and later wed Emily Theresa O’Donnell (1921-1991). By 1930, Hiram Billington and his wife had become the proprietors of a delicatessen in Camden County. Sadly, he died just six years later, at the age of fifty-two, in Camden County on 13 March 1936. Following funeral services, he was also laid to rest at the Pennsauken’s Arlington Park Cemetery.

Samuel Billington’s daughter, Louisa I. Billington, never married. A resident of the town of Milton in Northumberland County, she lived there with her sister, Alice Billington, during the early 1900s. According to federal census records, a seventy-three-year-old boarder, William Clingan, resided with them in 1900. By 1910, however, the sisters were financially stable enough to live together without taking in boarders. Sometime around 1920 the duo became a trio when Alice Billington wed iron worker Harry Fetzer (1872-1954). They then continued to reside together in Milton through the early 1940s. A week before Christmas in 1943, seventy-six-year-old Louisa Billington succumbed to complications from a cerebral hemorrhage at her home at 539 Shakespeare Avenue in Milton, and was laid to rest at the Harmony Cemetery in Milton.

Following her sister’s death, Alice (Billington) Fetzer continued to reside with her husband in Milton, Northumberland County. She was then widowed by her husband on 25 May 1954. Following funeral services, her husband was also buried at the Harmony Cemetery in Milton, according to his death certificate. Researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story have not yet determined what happened to Alice (Billington) Fetzer following her husband’s death.

Following her marriage in Camden, New Jersey to Raymond Benyard Llewellyn in 1898, Samuel Billington’s sister, Elizabeth (Billington) Llewellyn, settled with him in Camden, where her husband was employed as a label cutter after the turn of the century. Together, they welcomed the birth of Edna Mae Llewellyn (1899-1937), who was born in Camden on 30 August 1899 and later wed Dr. Ernest Francis Purcell (1896-1969). By 1910, Elizabeth (Billington) Llewellyn and her husband and their daughter were residing in Camden’s Second Ward. Also living with them were her sister, Fannie, and her husband’s mother. By 1930, Elizabeth and her husband and daughter had relocated to the Borough of Haddon Heights in Camden County. She then continued to reside there into the 1960s. After a long, full life, Elizabeth (Billington) Llewellyn died at the age of eighty-three in the Camden County Hospital on 8 September 1962, and was laid to rest at the Ewing Cemetery in Ewing, Mercer County, New Jersey.

Sources:

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Bell, Herbert C. History of Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, Including Its Aboriginal History; the Colonial and Revolutionary Periods; Early Settlement and Subsequent Growth; Political Organization; Agricultural, Mining, and Manufacturing Interests; Internal Improvements; Religious, Educational, Social, and Military History; Sketches of Its Boroughs, Villages, and Townships; Portraits and Biographies of Pioneers and Representative Citizens, Etc., Etc. Chicago, Illinois: Brown, Runk, & Co. Publishers: 1891.

- Bellington [sic, “Billington”], Samuel H., in Civil War Muster Rolls (Company C, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Bellington [sic, “Billington”], Samuel H., in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 (Company C, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Bellington [sic, “Billington”], Saml. H., in Death Certificates (Pennsylvania Hospital, City of Philadelphia, Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, date of death: 27 March 1893, date of burial: 28 March 1893). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Philadelphia City Archives.

- “Billington” (death and funeral notice of Samuel H. Billington), in “Died.” Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Philadelphia Inquirer, 30 March 1893.

- “Billington” (death and funeral notice of Samuel Billington’s son, Thomas A. Billington). Camden, New Jersey: Evening Courier, 11 April 1933.

- “Billington” (death notice of Samuel H. Billington’s daughter, Fannie Billington, which identifies her parents, date of death, and burial location), in “Deaths.” Camden, New Jersey: Camden Daily Courier, 2 December 1916.

- Billington, Fannie, Alice, Lizzie, and Hiram (Samuel Billington’s children), in New Jersey Census (City of Camden, Second Ward, Canden County, New Jersey, 1895). Trenton, New Jersey: New Jersey State Archives.

- Billington, Hiram (Samuel H. Billington’s son), Elsie, Earl, and Ralph, in U.S. Census (Pennsauken Township, Camden County, New Jersey, 1930). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Billington, Louisa and Alice (Samuel Billington’s sisters); and Clingan, William (boarder), in U.S. Census (Milton, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, 1900). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Billington, Louisa and Alice (Samuel Billington’s sisters), in U.S. Census (Milton, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, 1910, 1920). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Billington, Louisa (Samuel Billington’s sister); Fetzer, Harry and Alice (Samuel Billington’s brother-in-law and sister), in U.S. Census (Milton, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, 1930, 1940). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Billington, Maria (Samuel Billington’s mother), Samuel and Louisa (Samuel Billington’s sister), in U.S. Census (Borough of Sunbury, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, 1860).

- Billington, Mariah [sic, “Maria”], Hunter S., Mary E., Louisa E., Thomas A., Mary H., Mariah G., Anna F., Alice C., and Elizabeth H., in U.S. Census (Borough of Sunbury, First Ward, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, 1880). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Billington, Sam H., Mary, Maria G., Louisa, Thomas, and Margaret; Cadwalader, John (boarder); Thatcher, Harry (boarder); and McCollip/McCollin, Milton (boarder), in U.S. Census (Borough of Sunbury, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, 1870). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Billington, Samuel H., in Records of Burial Places of Veterans (Sunbury Cemetery, Sunbury, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Military Affairs.

- Billington, Samuel H., in U.S. Census (“Special Schedule. Surviving Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, and Widows, Etc.”: City of Camden, Camden County, New Jersey, June 1890). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Billington, Samuel H., in U.S. Civil War Pension General Index Cards (application no.: 219502, certificate no.: 143183, filed by the veteran, 16 May 1876). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Billington, Thomas (Samuel Billington’s father), in U.S. Census (Borough of Sunbury, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, 1840). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Billington, Thomas J. (Samuel Billington’s father), Maria, Samuel H., and Louisa, in U.S. Census (Borough of Sunbury, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, 1850). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Billington, Thomas A. (Samuel Billington’s son), Laura, Mabel, Myrtle, and Edith, in U.S. Census (City of Camden, Tenth Ward, Camden County, New Jersey, 1900). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Billington, Thomas (Samuel Billington’s son), Laura, Mabel, Myrtle, Edith, Thomas (son), Harold, and Fanny (Samuel Billington’s daughter and Thomas Billington’s sister), in New Jersey Census (City of Camden, Eleventh Ward, Camden County, New Jersey, 1905). Trenton, New Jersey: New Jersey State Archives.

- Billington, Thomas (Samuel Billington’s son), Laura, Mabel, Myrtle, Edith, Thomas (son), and Harold, in U.S. Census (City of Camden, Tenth Ward, Camden County, New Jersey, 1910). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Blankets, Socks, &c.” (mention of donation of blankets and clothing by Samuel Billington’s mother and other “ladies of Sunbury” to soldiers). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury Gazette, 21 December 1861.

- “Burglars About” (brief mention of a burglary at the boarding house operated by Samuel Billington’s mother, Maria Billington). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury American, 10 June 1871.

- “Contributions in Sunbury to the Sanitary Fair” (mention of Samuel Billington’s mother, Maria Billington). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury Gazette, 23 April 1864.

- Edith Billington (a granddaughter of Samuel Billington and a daughter of Thomas A. Billington), in Birth Records (City of Camden, Camden County, New Jersey, 5 March 1897). Camden, New Jersey: Office of Vital Statistics, City of Camden.

- “Flood at Williamsport.” Indiana, Pennsylvania: Indiana Weekly News, 5 June 1889.

- “Florida’s Role in the Civil War,” in Florida Memory. Tallahassee, Florida: State Archives of Florida.

- “For the American: To the Editor” (endorsement of the candidacy for Northumberland County sheriff of Samuel Billington’s father, Thomas A. Billington). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury Gazette, 12 April 1845.

- “Former Sunburians Die” (death notice of Samuel Billington’s mother, Maria Billington). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury American, 19 December 1890.

- “Fresh Flood Facts.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Northumberland County Democrat, 14 June 1889.

- “Funeral of Fannie Billington” (funeral notice of Samuel H. Billington’s daughter). Camden, New Jersey: Camden Post-Telegram, 26 December 1916.

- Gobin, John Peter Shindel. Personal Letters, 1861-1865. Northumberland, Pennsylvania: Personal Collection of John Deppen.

- Grodzins, Dean and David Moss. “The U.S. Secession Crisis as a Breakdown of Democracy,” in When Democracy Breaks: Studies in Democratic Erosion and Collapse, from Ancient Athens to the Present Day (chapter 3). New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2024.

- Harry Fetzer (a son-in-law of Samuel Billington and the husband of Alice (Billington) Fetzer), in Death Certificates (file no.: 43108, registered no.: 36, date of death: 25 May 1954). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics).

- History of Northumberland Co., Pennsylvania, With Illustrations Descriptive of Its Scenery, Palatial Residences, Public Buildings, Fine Blocks, and Important Manufactories, pp. 25 and 48-49. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Everts & Stewart, 1876.

- “In Chancery of New Jersey To Robert Briggs” (mention of Edith (Billington) Briggs, the wife of Robert Briggs, a daughter of Thomas A. Billington, and a granddaughter of Samuel H. Billington). Camden, New Jersey: Courier-Post, 10 April 1935.

- “Jeffersonian Republicanism and the Democratization of America,” in “US History I (AY Collection): The Early Republic.” New York: State University of New York and Lumen Learning.

- Lewallen [sic, “Llewellyn”], Raymond, Lizzie (Samuel H. Billington’s daughter) and Edna M.; Bellington, Anna F. and Hiram [sic, “Fannie Billington” and “Hiram L. Billington”] (Samuel H. Billington’s children), in U.S. Census (City of Camden, Camden County, New Jersey, 1900). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Llewalyn [sic, “Llewellyn”], Raymond, Lizzie (Samuel H. Billington’s daughter), Edna, and Anny; and Billington, Anna [sic, ” Fannie Billington”] (Samuel H.Billington’s daughter and Lizzie’s sister), in U.S. Census (City of Camden, Second Ward, Camden County, New Jersey, 1910). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Llewellyn, Raymond, Lizzie (Samuel H. Billington’s daughter) and Edna, in U.S. Census (City of Camden, Second Ward, Camden County, New Jersey, 1920). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Llewellyn, Raymond, Lizzie (Samuel H. Billington’s daughter) and Edna, in U.S. Census (Borough of Haddon Heights, Camden County, New Jersey, 1930). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Louisa Billington and Mrs. Maria Billington (mention of Samuel Billington’s mother, Maria Billington, in the death notice of Samuel’s sister, Louisa Billington). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury Gazette, 29 March 1863.

- Louisa I. Billington (Samuel Billington’s daughter), in Death Certificates (file no.: 112987, registered no.: 116, date of death: 18 December 1943). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics).

- “Married” (marriage notice of Thomas Billington and Maria Gobin, who would later become the parents of Samuel Billington). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury Gazette, 12 October 1839.

- “Mrs. Laura M. Billington” (a daughter-in-law of Samuel Billington and the wife of Thomas A. Billington). Camden, New Jersey: Evening Courier, 29 December 1927.

- Mrs. Maria Billington and Mrs. S. H. Billington (Samuel Billington’s mother and sister), in “Personalities.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury News, 26 June 1885.

- “Mrs. R. B. Llewellyn” (obituary of Samuel H. Billington’s daughter, Elizabeth (Billington) Llewellyn). Trenton, New Jersey: Trenton Evening Times, 10 September 1962.

- Mrs. S. H. Billington (death and funeral notice of Samuel Billington’s wife, Mary E. (Voute) Billington). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury News, 18 July 1890.

- “New Bakery” (announcement of the opening of Samuel Billington’s bakery in Sunbury). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury Gazette, 12 March 1864.

- Ross, John W., Jessie A., Elsie M., Sheppard P., Jeneva F., Blanche M., and Lilian G.; and Billington, Hiram L. (Samuel H. Billington’s son), in U.S. Census (Pennsauken Township, Camden County, New Jersey, 1910). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Roster of the 47th P. V. Inf.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 26 October 1930.

- S. Hunter Billington (notice of Samuel Billington’s discharge from “Capt. Gobin’s Company” due to “ill health”). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury Gazette, 20 June 1863.

- Samuel H. Billington and Mary E. Voute, in Marriage Records (Broad Street United Methodist Church, Burlington, Burlington County, New Jersey, 13 January 1864). Burlington, New Jersey: Broad Street United Methodist Church.

- Schmidt, Lewis G. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- “Sheriff’s Sales” (mention of Samuel Billington’s father, Sheriff Thomas A. Billington). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury Gazette, 12 December 1846.

- “The 47th Regiment in Battle” (mentions Samuel Billington’s leg wound, sustained during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury Gazette, 1 November 1862.

- “The Constables.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 29 March 1851.

- “The Great Storm of 1889,” in “Education.” Johnstown, Pennsylvania: Johnstown Area Heritage Association.

- “The History of the Forty-Seventh Regt. P. V.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Lehigh Register, 20 July 1870.

- “The New Sheriff.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury American, 24 October 1857.

- Thomas A. Billington (death notice, including cause of death, of Samuel Billington’s father), in “Deaths.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Northumberland County Republican, 15 March 1856.

- Thomas A. Billington (death notice, including cause of death, of Samuel Billington’s father), in “Died.” Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: The Lewisburg Chronicle, 21 March 1856.

- Thomas A. Billington (death notice of Samuel Billington’s father), in “Died.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury Gazette, 15 March 1856.

- Thomas A. Billington (groom and Samuel Billington’s son) and Laura M. Green, in Marriage Records (City of Camden, Camden County, New Jersey, 6 December 1890). Camden, New Jersey: Office of Vital Statistics, City of Camden.

- Thomas Billington, Jr. (a grandson of Samuel Billington and a son of Thomas A. Billington), in Birth Records (City of Camden, Camden County, New Jersey, 8 November 1900). Camden, New Jersey: Office of Vital Statistics, City of Camden.

- Wharton, Henry D. “Letters from the Sunbury Guards.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury American, 1861-1863.

You must be logged in to post a comment.