Anthony Bush, bandmaster of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry’s second Regimental Band (shown circa 1863-1864, public domain).

“Taps were sounded over the grave by Bernard McNulty, of this city. It appears that McNulty and Bush had agreed that the survivor was to sound taps over the grave of the first one to answer the call and McNulty, in performing his sorrowful duty, used the bugle which Bush had carried through so many battles for the Union.”

— The Morning Call, 20 December 1906

Born as Anton Benjamin Bush on 11 June 1835 in the Kingdom of Würtemberg, which is now part of Germany, Anthony B. Bush was a son of Francis Bush. Well educated, he pursued studies in music prior to his emigration from Germany in 1854. Upon his arrival in the United States, he adopted the given name spelling of “Anthony” and began to make a new life in the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, quickly becoming a regular performer at local church services.

He then married Susannah Weiser in 1856. A resident of Mauch Chunk in Carbon County, Pennsylvania (which would later merge with East Mauch Chunk to become the new borough of “Jim Thorpe” in 1953), Susannah (Weiser) Bush had been born in July 1838 as a daughter of Conrad Weiser.

After moving with his wife to Seigersville in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, Anthony Bush became the bandmaster of Seigersville’s local ensemble “which was considered the best in this vicinity during its time,” according to Bush’s obituary in the 17 December 1906 edition of The Allentown Leader.

Sometime around 1860, he and his wife welcomed daughter Ida to the world.

American Civil War

On 8 September 1862, twenty-seven-year-old Anthony B. Bush enrolled for military service in Allentown, Lehigh County. Also enrolling with him around this same time were several of his fellow members of the Seigerville band. He then officially mustered in for duty at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County on 5 November 1862 as a private with Company A of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, and was subsequently appointed as bandmaster of that unit’s Regimental Band. The second such regimental ensemble to be established for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, it would remain in service with the 47th Pennsylvania until the end of the war. (The 47th Pennsylvania’s first band had been formed under the leadership of Thomas Coates, but had been disbanded in September 1862 when the federal government deemed regimental bands an unnecessary expense as costs of the war continued to rise.)

Transported by ship to America’s Deep South, Private Bush subsequently connected with his new comrades at one of the 47th Pennsylvania’s duty stations in South Carolina or Florida during the late fall of 1862.

Concertizing as a Form of Diplomacy

Woodcut depicting the harsh climate at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida during the Civil War (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Under the leadership of Bandmaster Anthony B. Bush, the second regimental band of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers not only supported its regiment while it garrisoned Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Key West and the Dry Tortugas, Florida, it helped to build diplomatic “bridges” of understanding and cooperation between Union forces and the local citizenry in communities that were situated near those federal installations.

Based at Fort Taylor in Key West, Bandmaster Bush and his musicians were stationed there with the men of Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I, while the men from Companies D, F, H, and K were stationed at Fort Jefferson at a location that was accessible only by boat. In May of 1863, Musician Daniel Gackenbach, the band’s E-flat tuba player, was documented in records of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry as earning twenty-two dollars per month for his service. By June of 1863, two former men from the Easton Band plus a full brass section from Allentown were also members of the ensemble.

Colonel Tilghman H. Good, commanding officer, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (public domain image, circa 1863).

On Saturday, 25 July 1863, the Regimental Band performed for an audience in Key West, as part of a ceremony that was held by the leaders and residents of the city to honor the 47th Pennsylvania’s commanding officer, Colonel Tilghman H. Good. According to C Company Field Musician Henry D. Wharton:

On Saturday last, another sword presentation came off. This time Col. T. H. Good was the recipient, and the donors, the citizens. The sword is a magnificent one, and with the sash and belt, cost six hundred and ten dollars [the equivalent of more than twenty-five hundred U.S. dollars in 2025]. At 4 o’clock P.M., the two companies stationed at the Barracks, were marched to the Fort, where, with the three other companies doing duty, we formed in line, and under command of the Colonel were moved through several streets, to the front of the Custom House. A fine stand was erected, on the piazza of the building seats were placed for the ladies, flags were stretched across the streets, and everything so arranged as to give it the appearance of a holiday. On the stand I noticed Rear Admiral Bailey and Capt. Templeton of the Navy, Gen. Woodbury and staff, Captains Hook and McFarland of the Army, besides Thomas J. Boynton, U.S. District Attorney for the Southern District of Florida. The articles were presented to Col. Good by Mr. Maloney, a lawyer of this city who complimented the Colonel on the fine bearing and appearance of his regiment. He spoke of the trials the citizens had under the military commander Col. Good relieved; of their being saved from banishment and separation of friends and all they held dear; of the wholesome administration of the Colonel, while in command of this Department, and in conclusion placed the sword in Col. Good’s hand, telling him if he used it as he used his own at Pocotaligo, the citizens would be satisfied, and have no fear of it ever being dishonored. The Colonel replied in a very short speech, saying, what he had done was by instructions by Head Quarters — thanked him for the present, and said as he then felt, he could assure the good people of Key West, that their present would never be dishonored through himself. As the Col. concluded, the Band of our regiment struck up the tune ‘Bully for You,’ which was received with cheer after cheer. Several speeches were made, among others, one by Mr. Boynton. He is a Missourian and received his appointment from the present administration. Although a southerner, he is Union all over. He said he hoped the cannon and sword would soon be made into plow shares and pruning hooks, but not until every rebel was on his knees willing to obey the laws and pay respect to the Star Spangled Banner. The Band then played several National airs, cheers were given for the Union, President Lincoln, Army and Navy, Gen. Woodbury, Admiral Baily, &c., when the meeting adjourned, and we were marched to our different quarters, well pleased with the proceedings, though I must say, completely worn out from fatigue and extreme heat.

In a letter to the Sunbury American on 23 August 1863, Henry Wharton described Thanksgiving celebrations held by the regiment and residents of Key West and a yacht race the following Saturday at which participants had “an opportunity of tripping the ‘light, fantastic toe,’ to the fine music of the 47th Band, lead by that excellent musician, Prof. Bush.”

1864

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers experienced a significant change when members of the regiment were ordered to expand the Union’s reach by sending part of the regiment north to retake Fort Myers, a federal installation that had been abandoned in 1858, following the federal government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. In response, Company A Captain Richard Graeffe and a detachment of his subordinates traveled north, captured the fort and began conducting cattle raids to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across the region. They subsequently turned their fort not only into their base of operations, but into a shelter for pro-Union supporters, escaped slaves, Confederate deserters, and others fleeing Rebel troops.

Red River Campaign

Map of key 1864 Red River Campaign locations, showing the battle sites of Sabine Cross Roads, Pleasant Hill and Mansura in relation to the Union’s occupation sites at Alexandria, Grand Ecore, Morganza, and New Orleans (excerpt from Dickinson College/U.S. Library of Congress map, public domain).

Meanwhile, the Regimental Band and all of the other companies from the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had begun preparing for the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding the steamer Charles Thomas, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by the men from Companies E, F, G, and H.

Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost-fully-reunited-regiment moved by train to Brashear City (now Morgan City), before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the 19th Corps (XIX) of the United States’ Army of the Gulf, and became the only regiment from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to serve in the Red River Campaign, commanded by Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks. (Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the soldiers from Company A were assigned to detached duty while awaiting transport that enabled them to reconnect with their regiment at Alexandria, Louisiana on 9 April.)

The early days on the ground quickly woke Bandmaster Anthony Bush and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers up to just how grueling their new phase of duty would be. From 14-26 March, most members of the 47th marched for Alexandria and Natchitoches, near the top of the L-shaped state. Among the towns that the 47th Pennsylvanians passed through were New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington.

From 4-5 April 1864, the regiment added to its roster of young Black soldiers when Aaron Bullard (later known as Aaron French), James Bullard, John Bullard, Samuel Jones, and Hamilton Blanchard (also known as John Hamilton) enrolled for military service with the 47th Pennsylvania at Natchitoches. According to their respective entries on regimental muster rolls, the men were officially mustered into the regiment on 22 June at Morganza, Louisiana. Several of their entries noted that they were assigned the rank of “Colored Cook” while others were given the rank of “Under-Cook.”

Often short on food and water throughout their long, harsh-climate trek, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill (now the Village of Pleasant Hill) the night of 7 April, before continuing on the next day.

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the second division, sixty members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were cut down on 8 April 1864 during the intense volley of fire in the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (also known as the Battle of Mansfield due to its proximity to the town of Mansfield). The fighting waned only when darkness fell. The exhausted, but uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded and dead. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up unto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate Major-General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner who was the son of Zachary Taylor, a former president of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the Union force, the men of the 47th were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

During that engagement (now known as the Battle of Pleasant Hill), the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers succeeded in recapturing a Massachusetts artillery battery that had been lost during the earlier Confederate assault. Unfortunately, the regiment’s second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, and its two color-bearers, Sergeants Benjamin Walls and William Pyers, were wounded. (Alexander sustained wounds to both of his legs, and Walls was shot in the left shoulder as he attempted to mount the 47th Pennsylvania’s colors on caissons that had been recaptured, while Pyers was wounded as he grabbed the flag from Walls to prevent it from falling into Confederate hands.) All three survived the day, however, and continued to serve with the regiment, but many others, like K Company Sergeant Alfred Swoyer, were killed in action during those two days of chaotic fighting, or were wounded so severely that they were unable to continue the fight. (Swoyer’s final words were, “They’re coming nine deep!” Shot in the right temple shortly afterward, his body was never recovered).

Still others were captured by Confederate troops, marched roughly one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford, a Confederate Army prison camp near Tyler, Texas, and held there as prisoners of war until they were released during a series of prisoner exchanges that began on 22 July and continued through November. At least two members of the regiment never made it out of that prison camp alive; another died at a Confederate hospital in Shreveport.

Meanwhile, as the captured 47th Pennsylvanians were being spirited away to Camp Ford, the bulk of the regiment was carrying out orders from senior Union Army leaders to head for Grand Ecore, Louisiana. Encamped there from 11-22 April, the Union soldiers engaged in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications.

They then moved back to Natchitoches Parish on 22 April. While they were in route, they were attacked again, this time, at the rear of their retreating brigade, but they were able to end the encounter quickly and move on to reach Cloutierville at 10 p.m. that same night (after a forty-five-mile march).

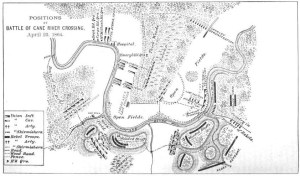

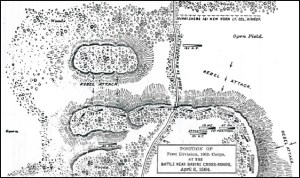

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were stationed just to the left of the “Thick Woods” with Emory’s 2nd Brigade, 1st Division as shown on this map of Union troop positions for the Battle of Cane River Crossing at Monett’s Ferry, Louisiana, 23 April 1864 (Major-General Nathaniel Banks’ official Red River Campaign Report, public domain).

The next morning (23 April), episodic skirmishing quickly roared into the flames of a robust fight. As part of the advance party led by Union Brigadier-General William Emory, the 47th Pennsylvanians took on the Confederate Cavalry of Brigadier-General Hamilton Bee in the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the affair at Monett’s Ferry” or the “Cane River Crossing”).

Responding to a barrage from the Confederate Artillery’s twenty-pound Parrott guns and from enemy troops positioned atop a bluff and near a bayou, Brigadier-General Emory directed one of his brigades to keep Bee’s Confederate troops busy while sending two other brigades to find a safe spot for the Union’s forces to cross the Cane River. As part of “the beekeepers,” the 47th Pennsylvania supported Smith’s artillery.

Meanwhile, additional troops under Smith’s command attacked Bee’s flank to force a Rebel retreat, and then erected a series of pontoon bridges that enabled the 47th Pennsylvania and other Union regiments to make the Cane River Crossing by the next day. As the Confederates retreated, they torched their own food stores, as well as the cotton supplies of their fellow southerners. In a letter penned from Morganza, C Company Musician Henry Wharton described what had happened:

Our sojourn at Grand Score was for eleven days, during which time our position was well fortified by entrenchments for a length of five miles, made of heavy logs, five feet high and six feet wide, filled in with dirt. In front of this, trees were felled for a distance of two hundred yards, so that if the enemy attacked we had an open space before us which would enable our forces to repel them and follow if necessary. But our labor seemed to the men as useless, for on the morning of 22d April, the army abandoned these works and started for Alexandria. From our scouts it was ascertained that the enemy had passed some miles to our left with the intention of making a stand against our right at Bayou Cane, where there is a high bluff and dense woods, and at the same attack Smith’s forces who were bringing up the rear. This first day was a hard one for the boys, for at 10 o’clock at night they made Cloutierville, a distance of forty drive miles. On that day our rear was attacked which caused our forces to reverse their front and form in line of battle, expecting too, to go back to the relief of Smith, but he needed no assistance, sending word to the front that he had ‘whipped them, and could do it again.’ It was well that Banks made so long a march on that day, for on the next we found the enemy prepared to carry out their design of attacking us front and rear. Skirmishing commenced early in the morning and as our columns advanced he fell back towards the bayou, when we soon discovered the position of their batteries on the bluff. There was then an artillery duel by the smaller pieces, and some sharp fighting by the cavalry, when the ‘mule battery,’ twenty pound Parrott guns opened a heavy fire, which soon dislodged them, forcing the chivalry to flee in a manner not at all suitable to their boasted courage. Before this one cavalry, the 3d Brigade of the 1st Div., and Birges’ brigade of the second, had crossed the bayou and were doing good service, which, with the other work, made the enemy show their heels. The 3d brigade done some daring deeds in this fight, as also did the cavalry. In one instance the 3d charged up a hill almost perpendicular, driving the enemy back by the bayonet without firing a gun. The woods on this bluff was so thick that the cavalry had to dismount and fight on foot. During the whole of the day, our brigade, the 2d, was supporting artillery, under fire all the time, and could not give Mr. Reb a return shot.

While we were fighting in front, Smith was engaged some miles in the rear, but he done his part well and drove them back. The rebel commanders thought by attacking us in the rear, and having a large face on the bluffs, they would be able to capture our train and take us all prisoners, but in this they were mistaken, for our march was so rapid that we were on them before they had thrown up the necessary earthworks. Besides they underrated the amount of our artillery, calculating from the number engaged at Pleasant Hill. The rebels say it ‘seems as though the Yankees manufacture, on short notice, artillery to order, and the men are furnished with wings when they wish to make a certain point.’

The damage done to the Confederate cause by the burning of cotton was immense. On the night of the 22d our route was lighted up for miles and millions of dollars worth if this production was destroyed. This loss will be felt more by Davis & Co., than several defeats in this region, for the basis of the loan in England was on the cotton in Louisiana.

After the rebels had fled from the bluff the negro troops put down the pontoons, and by ten that night we were six miles beyond the bayou safely encamped. The next morning we moved forward and in two days were in Alexandria. Johnnys followed Smith’s forces, keeping out of range of his guns, except when he had gained the eminence across the bayou, when he punished them (the rebs) severely.

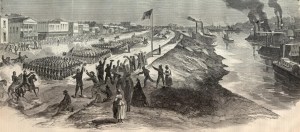

The Union’s Army of the Gulf marched into Alexandria, Louisiana, during the weekend of April 22, 1864 (Harper’s Weekly, public domain; click to enlarge).

Having finally reached Alexandria on 26 April, they learned that they would remain at their latest new camp for at least two weeks. Placed temporarily under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, they were assigned to the hard labor of construction work, helping to erect “Bailey’s Dam,” a timber structure that was designed to enable Union gun boats to safely navigate the fluctuating water levels of the Red River. According to Musician Henry Wharton:

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gun boats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people will eat), so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the iron clads down the river. After a great deal of labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic, chute], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’ The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gunboat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

Continuing their march, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers headed toward Avoyelles Parish. According to Wharton:

On Sunday, May 15th, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of the Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad where with the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. — We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed into line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired, and we advanced ’till dark, when the forces halted for the night with orders to rest on their arms. ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee.

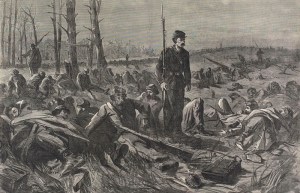

“Sleeping on Their Arms” by Winslow Homer (Harper’s Weekly, 21 May 1864).

“Resting on their arms” (half-dozing, without pitching their tents, and with their rifles right beside them), they were now positioned just outside of Marksville, on the eve of the 16 May 1864 Battle of Mansura, which unfolded as follows, according to Wharton:

Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, they reached Missoula [sic, Mansura], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic, maneuvering] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic, were] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain directly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport [sic, Simmesport] on the Achafalaya [sic, Atchafalaya] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over.– The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of the army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic, there] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.

Union Army base at Morganza Bend, Louisiana, circa 1863-1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Continuing on, the healthy members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry marched for Simmesport and then Morganza, where they made camp again. While encamped there, the nine formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the regiment in Beaufort, South Carolina (1862) and Natchitoches, Louisiana (1864) were officially mustered into the regiment between 22-24 June.

The regiment then moved on and arrived in New Orleans in late June. On the Fourth of July, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers received orders to return to the East Coast. Three days later, they began loading the regiment and its men onto ships, a process that unfolded in two stages. Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I boarded the U.S. Steamer McClellan on 7 July and departed that day, while the members of Companies B, G and K remained behind, awaiting transport. (The second group later departed aboard the Blackstone, weighing anchor and sailing forth at the end of that month. Arriving in Virginia, on 28 July, that group then reconnected with the first group at Monocacy.)

As a result, the first group of 47th Pennsylvanians (the men from Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I) ended up in close enough proximity to encounter President Abraham Lincoln before moving on to fight in the Battle of Cool Spring at Snicker’s Gap in mid-July.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

“The Rendezvous of the Virginians at Halltown, Virginia, 5 p.m. on April 18, 1861 to March on Harper’s Ferry” (D. H.Strother, Harper’s Weekly, 11 May 1861, public domain).

Assigned to the Union Army’s Middle Military Division in Virginia at the beginning of August in 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were attached to the Army of the Shenandoah, which was engaged in a series of military actions between Halltown, Berryville, Middletown, Charlestown, and Winchester. As summer waned, according to historian Lewis Schmidt, regimental military records noted that Bandmaster Bush was paid for his service with the 47th’s Regimental Band No. 2 on 31 August:

[The] 47th was paid this date by a Major Eaton. Various members of the band were paid by the 47th’s Council of Administration effective through this date, generally for a three to four month period. The men and accounts are as follows: Anthony B. Bush, $157.50; Eugene Walters [sic] and John Rupp, each $100; David Gackenback [sic, “Daniel Gackenbach“], $52.50 Henry Kern and George Frederick, each $60; Henry Tool, $30; and Lewis Sponheimer, Harrison Handwerk, Edwin Dreisbach, Daniel Dachradt [sic, “Daniel Dachrodt“] and William Heckman, each $16.”

Just over two weeks later, Bandmaster Bush was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate of disability at Berryville, Virginia on 18 September 1864.

* Note: Although the 1906 obituary of Anthony B. Bush would subsequently state that he had been awarded the rank of lieutenant, historian Samuel P. Bates only noted a rank of private for Anthony Bush in his book, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5.

After the War

Following his honorable discharge from the military, Anthony Bush returned home to Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, where he resumed life as a conductor and music teacher. According to a 1906 edition of Allentown’s Morning Call newspaper, he was known as “an expert musician” who “devoted his time entirely to music.”

He was also a family man. Sometime around 1865, he and his wife Susannah welcomed a daughter, Emma Bush, followed by sons Charles (circa 1868), Francis (circa 1870) and Robert Bush, the latter of whom was born in January 1875. By 1880, he and Susannah were living in South Bethlehem, Northampton County with Ida, Emma, Charles, Francis, and Robert. Another daughter, Nellie Bush, arrived in August 1885.

By 1890, he had resettled his family in East Catasauqua; in 1900, he and his wife were living there only with their children, Robert and Nellie.

A Musical Talent Who Was Still in Demand After the Turn of the Century

Unidentified Civil War Bugler (pencil sketch by Alfred Waud, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

On 22 June 1902, Anthony Bush sounded the final bugle call for a member of his former Civil War regiment — P. F. Remmel. The 23 June 1902 edition of The Allentown Leader reported on the funeral as follows:

The funeral of P. F. Remmel Sunday afternoon was the most distinctive military funeral given to any Allentown veteran for many years. He was the oldest veteran in the city, and Anthony Bush of Catasauqua, who was a member of the 47th Regiment Band, the same command to which Mr. Remmel belonged, sounded the taps over his grave.

Company E, Second Regiment, S. of V. Reserves, was out with 50 members and fired the salute over the grave. Yeager Post No. 13, G.A.R., had 45 men in line; the Union Veteran Legion 25 and E. B. Young Post 87 was [sic] well represented. At the grave Yeager Post and the Veteran Legion performed their rituals. Rev. G. F. Gardner was the officiating clergyman. The S. of V. Drum Corps furnished appropriate music. The dirges and marching music were particularly commented upon.

Illness, Death and Burial

The gravestone of Private Anthony Bush, bandmaster, Regimental Band No. 2, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, Fairview Cemetery, West Catasauqua, Pennsylvania (public domain).

After suffering from apoplexy and dropsy for the final six months of his life, Anthony Benjamin Bush passed away at the age of seventy-two at his home in East Catasauqua, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania on Monday, 17 December 1906.

His funeral services were conducted at his home by the Rev. Dr. J. D. Schindel and Rev. J. F. Lambert, beginning at 1 p.m. on Wednesday, 19 December 1906. Anthony B. Bush was then interred at the Fairview Cemetery in Bethlehem, Northampton County, Pennsylvania. According to Allentown’s Morning Call newspaper:

Friend Played Taps

As Had Been Agreed by Veteran Buglers Before Bush DiedThe funeral of Anthony B. Bush was held yesterday afternoon [19 December 1906] from his home, on Race street, East Catasauqua, and interment made in Fairview Cemetery, West Catasauqua. A large number of friends and members of organizations which he had been affiliated with attended the obsequies, and the pall-bearers were furnished by the Allentown Camp of the Union Veteran Legion, and included W. C. Miller, A. J. Helffrich, O. D. Giffin, Captain W. H. Bartholomew, E. W. Reed and William Ehrich.

Taps were sounded over the grave by Bernard McNulty, of this city [Allentown]. It appears that McNulty and Bush had agreed that the survivor was to sound taps over the grave of the first one to answer the call and McNulty, in performing his sorrowful duty, used the bugle which Bush had carried through so many battles for the Union.

He was survived by his widow, Susannah (Weiser) Bush; seven children: Charles Bush (Allentown, Pennsylvania); Francis, Robert and Nellie Bush (East Catasauqua, Pennsylvania); George Bush (Johnstown, Pennsylvania); Mrs. Harry Klein (Bethlehem, Pennsylvania); and Mrs. August Petri (East Catasauqua); multiple grandchildren; and his sisters: Mrs. Frances Miller (Chicago, Illinois) and Mrs. S. Schlipf (Muscatine, Iowa).

His gravestone was inscribed with “Anton” — the first name that he had been given at birth.

Sources:

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- “Civil War Military Bands: Their Purpose and Composition.” Washington, D.C.: American Battlefield Trust, 28 September 2020 (revised 12 May 2021).

- Civil War Veterans’ Card File. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Death Certificate (Prof. Anton B. Bush, file no.; 113233, registered no.: 186). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- “Death of Veteran Musician: Anthony B. Bush Expires After Long Sickness.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Leader, 17 December 1906.

- “Florida’s Role in the Civil War,” in Florida Memory. Tampa, Florida: Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida, retrieved online 15 January 2020.

- “Friend Played Taps” (report on the funeral of Anthony B. Bush). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 20 December 1906.

- Grodzins, Dean and David Moss. “The U.S. Secession Crisis as a Breakdown of Democracy,” in When Democracy Breaks: Studies in Democratic Erosion and Collapse, from Ancient Athens to the Present Day (chapter 3). New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2024.

- “July 25” (1995 photograph of the sword presented to Colonel Tilghman H. Good, commanding officer of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, by the citizens of Key West, Florida on July 25, 1863), in “Florida Keys History Center.” Key West, Florida: Key West Library, retrieved online August 16, 2025.

- “Military Funeral: Appropriate Services at Burial of Town’s Oldest Veteran [P. F. Remmel].” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Leader, 23 June 1902.

- “Roster of the 47th P. V. Inf.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 26 October 1930.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- Stockham, Jeff. “Civil War Music Instruments” (video), in Making Music (magazine). Syracuse, New York: Bentley Hall, Inc., 15 July 2013.

- “The Civil War Bands,” in Band Music from the Civil War Era. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved from LOC website, September 2015.

- “The History of the Forty-Seventh Regt. P. V.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Lehigh Register, 20 July 1870.

- U.S. Census (1880, 1890). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- U.S. Veterans’ Schedule (1890). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Wharton, Henry D. “Letters from the Sunbury Guards,” 1861-1865. Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury American.

You must be logged in to post a comment.