“From 1820 to 1870, over seven and a half million immigrants came to the United States,” according to Philadelphia’s Independence Hall Association, “more than the entire population of the country in 1810.”

Nearly all of them came from northern and western Europe — about a third from Ireland and almost a third from Germany. Burgeoning companies were able to absorb all that wanted to work. Immigrants built canals and constructed railroads. They became involved in almost every labor-intensive endeavor in the country. Much of the country was built on their backs.

One of the German émigrés who helped his adopted homeland to progress in this way was Conrad J. Volkenand, a farmer who had raised pigs prior to beginning his own journey in search of religious and political freedom and greater economic opportunity. Born on 23 December 1839 in Widdershausen, Hesse, he arrived in the United States sometime around 1854, and apprenticed as a mason while residing in Tamaqua, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. Following his completion of that training, he moved to Schuylkill County’s nearby Borough of Ashland.

By 1861, he had relocated again — this time to the great Keystone State’s Luzerne County, where he secured employment as a blacksmith in Stockton. Unfortunately, his new-found stability was short lived as his adopted homeland descended into the all-too-familiar darkness of disunion.

Civil War Military Service

George Junker announces the formation of a company of German/German-American soldiers for Civil War service (Der Lecha Caunty Patriot, 7 August 1861, public domain).

Like many of his fellow German immigrants, Conrad J. Volkenand became one of America’s earliest responders to President Abraham Lincoln’s mid-April 1861 call for seventy-five thousand volunteers to defend the U.S. capital following the fall of Fort Sumter to Confederate troops. After enrolling for Civil War military service in Luzerne County on 21 August 1861 at the age of twenty-one, he then officially mustered in for duty at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County on 17 August 1861 as a first sergeant with Company K of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

* Note: Company K was raised with the intent of being an “all-German company” composed of native-born and naturalized German-Americans, as well as relatively recent immigrants from Germany. Its founder, George Junker, was a twenty-six-year-old German native who lived and worked as a tombstone carver in Allentown, Lehigh County. Der Lecha Caunty Patriot, the Lehigh Valley’s Allentown-based, German language newspaper, praised him for his initiative in its 7 August 1861 edition. Roughly translated, the announcement read:

It’s good to hear, that Sergeant Junker, of this city, is bringing a new German company of the Lehigh Valley along under the terms of recruitment for the duration of the war. It will be particularly sweet to him if such Germans already here or abroad, who have served as soldiers, sign up immediately for him, and join the company. It can be noted that Sergeant Junker, who recently returned from the scene of the war, has done important services for the Union side in this time, and has all capabilities that are necessary for a Captain. We wish him the best luck for his company.

Junker was subsequently assigned to command the men he recruited as Captain of Company K. Interestingly, Conrad Volkenand entered the service as a first sergeant — a rank several grades higher than what most newly-enlisted soldiers were typically accorded, signaling the likelihood that he had had some degree of military training or service prior to his emigration from Germany.

Following a brief training period in light infantry tactics at Camp Curtin, First Sergeant Volkenand and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians were transported by rail to Washington, D.C. Stationed roughly two miles from the White House, they pitched tents at “Camp Kalorama” on the Kalorama Heights near Georgetown beginning 21 September. The next day, Henry D. Wharton, a Musician with the regiment’s C Company, penned the following update to his hometown newspaper, the Sunbury American:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September 1861] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so wrapt [sic] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on dis-covering they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.

Col. Good, who has command of our regiment, is an excellent man and a splendid soldier. He is a man of very few words, and is continually attending to his duties and the wants of the Regiment.

…. Our Regiment will now be put to hard work; such as drilling and the usual business of camp life, and the boys expect and hope an occasional ‘pop’ at the enemy.

Chain Bridge across the Potomac above Georgetown looking toward Virginia, 1861 (The Illustrated London News, public domain).

Acclimated somewhat to their new way of life, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers became part of the U.S. Army when they were officially mustered into federal service on 24 September. Three days later, the regiment was attached to Brigadier-General Isaac Stevens’ 3rd Brigade, which also included the 33rd, 49th and 79th New York regiments. By that afternoon, they were on the move again. Ordered onward by Brigadier-General Silas Casey, the Mississippi rifle-armed infantrymen marched behind their Regimental Band until reaching Camp Lyon, Maryland on the Potomac River’s eastern shore. At 5 p.m., they joined the 46th Pennsylvania in moving double-quick (one hundred and sixty-five steps per minute using thirty-three-inch steps) across the “Chain Bridge” marked on federal maps, and continued on for roughly another mile before being ordered to make camp.

The next morning, they broke camp and moved again. Marching toward Falls Church, Virginia, they arrived at Camp Advance around dusk. There, about two miles from the bridge they had crossed a day earlier, they re-pitched their tents in a deep ravine near a new federal fort under construction (Fort Ethan Allen). They had completed a roughly eight-mile trek, were situated fairly close to Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith’s headquarters, and were now part of the massive Army of the Potomac. Under Smith’s leadership, their regiment and brigade would help to defend the nation’s capital from the time of their September arrival through late January when they would be shipped south.

Once again, Company C Musician Henry Wharton recapped the regiment’s activities, noting, via his 29 September letter home to the Sunbury American, that the 47th had changed camps three times in three days:

On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this Camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders.)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march this morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six tons of hay. A very nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment….

The Big Chestnut Tree, Camp Griffin, Langley, Virginia, 1861 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Sometime during this phase of duty, as part of the 3rd Brigade, First Sergeant Conrad Volkenand and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians were moved to a site they initially christened “Camp Big Chestnut” — so named for a large chestnut tree located nearby. The site, situated roughly tenmiles from Washington, D.C., would eventually become known to the Keystone Staters as “Camp Griffin.”

On October 11, they marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads. In a mid-October letter home, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin (the leader of C Company who would be promoted in 1864 to lead the entire 47th Regiment) reported that companies D, A, C, F and I (the 47th Pennsylvania’s right wing) were ordered to picket duty after the left wing companies (B, E, G, H, and K) had been forced to return to camp by Confederate troops. In his letter of 13 October, Henry Wharton described their duties, as well as their new home:

The location of our camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets. Last night, however, they (the Rebels) calculated wide of their mark; some of the New York 33d boys were out on picket; some fourteen or fifteen shots were exchanged, when our side succeeded in bringing to the dust, (or rather mud,) an officer and two privates of the enemy’s mounted pickets. The officer was shot by a Lieutenant in Company H [?], of the 33d.

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort, (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually, but the hardest was on picket from last Thursday morning ‘till Saturday morning – all the time four miles from camp, and both of the nights the rain poured in torrents, so much so that their clothes were completely saturated with the rain. They stood it nobly – not one complaining; but from the size of their haversacks on their return, it is no wonder that they were satisfied and are so eager to go again tomorrow. I heard one of them say ‘there was such nice cabbage, sweet and Irish potatoes, turnips, &c., out where their duty called them, and then there was a likelihood of a Rebel sheep or young porker advancing over our lines and then he could take them as ‘contraband’ and have them for his own use.’ When they were out they saw about a dozen of the Rebel cavalry and would have had a bout with them, had it not been for…unlucky circumstance – one of the men caught the hammer of his rifle in the strap of his knapsack and caused his gun to fire; the Rebels heard the report and scampered in quick time….

On Friday morning, 22 October 1861, the 47th engaged in a divisional review, described by historian Lewis Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” Also around this time, Captain Junker issued his first Special Order:

I. 15 minutes after breakfast every tent will be cleaned. The commander of each tent will be held responsible for it, and every soldier must obey the orders of the tent commander. If not, said commanders will report such men to the orderly Sgt. who will report them to headquarters.

II. There will be company drills every two hours during the day, including regimental drills with knapsacks. No one will be excused except by order of the regimental surgeon. The hours will be fixed by the commander, and as it is not certain therefore, every man must stay in his quarter, being always ready for duty. The roll will be called each time and anyone in camp found not answering will be punished the first time with extra duty. The second with carrying the 75 lb. weights, increased to 95 lb. The talking in ranks is strictly forbidden. The first offense will be punished with carrying 80 lb. weights increased to 95 lbs. for four hours.

Meanwhile, while other members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers shipped home muskets and other souvenirs seized from Confederate troops during this phase of duty, First Sergeant Conrad Volkenand was safeguarding an entirely different type of keepsake — a Bible that he would carry with him for the remainder of his days — one given to him on 12 November 1861 by a chaplain stationed with him at Camp Griffin.

Around this same time, Henry Wharton was penning another letter home:

This morning our brigade was out for inspection; arms, accoutrements [sic], clothing, knapsacks, etc, all were out through a thorough examination, and if I must say it myself, our company stood best, A No. 1, for cleanliness. We have a new commander to our Brigade, Brigadier General Brannen [sic], of the U.S. Army, and if looks are any criterion, I think he is a strict disciplinarian and one who will be as able to get his men out of danger as he is willing to lead them to battle….

The boys have plenty of work to do, such as piquet [sic] duty, standing guard, wood-chopping, police duty and day drill; but then they have the most substantial food; our rations consist of fresh beef (three times a week) pickled pork, pickled beef, smoked pork, fresh bread, daily, which is baked by our own bakers, the Quartermaster having procured portable ovens for that purpose, potatoes, split peas, beans, occasionally molasses and plenty of good coffee, so you see Uncle Sam supplies us plentifully….

A few nights ago our Company was out on piquet [sic]; it was a terrible night, raining very hard the whole night, and what made it worse, the boys had to stand well to their work and dare not leave to look for shelter. Some of them consider they are well paid for their exposure, as they captured two ancient muskets belonging to Secessia. One of them is of English manufacture, and the other has the Virginia militia mark on it. They are both in a dilapidated condition, but the boys hold them in high estimation as they are trophies from the enemy, and besides they were taken from the house of Mrs. Stewart, sister to the rebel Jackson who assassinated the lamented Ellsworth at Alexandria. The honorable lady, Mrs. Stewart, is now a prisoner at Washington and her house is the headquarters of the command of the piquets [sic]….

Since the success of the secret expedition, we have all kinds of rumors in camp. One is that our Brigade will be sent to the relief of Gen. Sherman, in South Carolina. The boys all desire it and the news in the ‘Press’ is correct, that a large force is to be sent there, I think their wish will be gratified….

On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review — one that was overseen this time by the regiment’s commanding officer, Colonel Tilghman Good. Their afternoon was then devoted to brigade and division drills. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

1862

U.S. Naval Academy Barracks and temporary hospital, Annapolis, Maryland, circa 1861-1865 (public domain).

Next ordered to move from their Virginia encampment back to Maryland, First Sergeant Conrad Volkenand and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862. Marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church, they were then transported by rail to Alexandria, where they boarded the steamship City of Richmond. Upon reaching the Washington Arsenal, they were reequipped, and then marched off for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington, D.C. The next afternoon, they hopped cars on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland. Arriving around 10 p.m., they were assigned quarters in barracks at the Naval Academy. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship Oriental.

By the afternoon of Monday, 27 January, the 47th Pennsylvanians had commenced boarding — enlisted men first, followed by the officers. Ferried to the big steamship by smaller steamers, they then sailed away for the Deep South at 4 p.m. per the directive of Brigadier-General Brannan. They were headed for Florida which, despite its secession from the United States, was still strategically important due to the presence of Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Key West and the Dry Tortugas.

By early February 1862, the 47th Pennsylvanians were disembarking in Key West, Florida, where they were immediately assigned to garrison duty at Fort Taylor. Drilling daily in heavy artillery tactics, they also strengthened fortifications, felled trees and built new roads. During the weekend of Friday, 14 February, they paraded through the streets of Key West and attended area church services to introduce themselves to local residents.

Unfortunately, disease became a most fearsome foe for the 47th during this phase of duty as multiple members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were felled by typhoid fever, dysentery, and/or chronic diarrhea, and confined to the post hospital at Fort Taylor. A fair number of those then died, and were laid to rest at the post cemetery. Still others were deemed too ill to continued serving and were honorably discharged on surgeons’ certificates of disability.

From mid-June through July, First Sergeant Conrad Volkenand and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians were ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina, where they made camp before being housed in the Department of the South’s Beaufort District. Picket duties north of the 3rd Brigade’s camp were rotated among the regiments present, putting soldiers at increased risk from sniper fire, including the men from K Company who served on picket duty beginning 5 July.

Saint John’s Bluff, Florida and the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina

J.H. Schell’s illustration of the earthenworks surrounding the Confederate battery atop Saint John’s Bluff, overlooking the Saint John’s River in Florida (1862, public domain).

During a return expedition to Florida beginning 30 September, the 47th joined with the 1st Connecticut Battery, 7th Connecticut Infantry, and part of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry in assaulting Confederate forces at their heavily protected camp at Saint John’s Bluff overlooking the Saint John’s River. Trekking and skirmishing through roughly twenty-five miles of dense swampland and forests after disembarking from ships at Mayport Mills on 1 October, the 47th Pennsylvanians moved inland where, on 3 October, they captured artillery and ammunition stores that had been abandoned by Confederate forces as they fled the bombardment of the bluff by Union gunboats.

The Union detachment was then ordered to press on. Advancing up the river, the 47th’s Companies E and K then participated in the 5 October capture of Jacksonville, Florida as part of a special mission led by Captain Charles Yard.

The rebel steamer Governor Milton, captured by the U.S. flotilla on the Saint John’s River, Florida (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Florida Memory Project, State Archives of Florida, public domain).

A day later, while protected by the Union gunboat Hale, they sailed another 200 miles upriver, aboard the Union gunboat Darlington (formerly a Confederate steamer). As they neared Hawkinsville, they also seized the Governor Milton, a Confederate steamer engaged in furnishing troops, ammunition and other supplies to Confederate Army units throughout the region, sailed it back down river, and moved it behind Union lines.

From 21-23 October, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren (“G. W.”) Alexander, the entire 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry next joined with other Union regiments to engage the heavily protected Confederate forces in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina — including at Frampton’s Plantation and the Pocotaligo Bridge. Their primary mission was to destroy that bridge — a key piece of the South’s railroad infrastructure that Confederate leaders would not allow to be eliminated without a fight.

Harried by snipers en route to the Pocotaligo Bridge, the Union troops met resistance from yet another entrenched, heavily fortified Confederate battery which opened fire on them as they entered an open cotton field. Those headed toward higher ground at the Frampton Plantation fared no better as they encountered artillery and infantry fire from the surrounding forests. But the Union soldiers would not give in; grappling with the Confederates where they found them, they pursued the Rebels for four miles as the Confederate Army retreated to the bridge. After relieving the 7th Connecticut, the 47th Pennsylvanians engaged in two hours of intense fighting with the enemy before being forced to withdraw by their depleted ammunition.

Losses for the 47th Pennsylvania were significant. Captain Charles Mickley of G Company died where he fell from a gunshot wound to his head while K Company Captain George Junker and several of his enlisted men were mortally wounded by minie balls during the intense fighting near the Frampton Plantation. All three died the next day while being treated for their wounds at the Union Army’s General Hospital at Hilton Head, South Carolina.

Private Gottlieb Fiesel, whose skull was fractured by an exploding artillery shell, somehow survived, but contracted meningitis following brain surgery, and passed away at Hilton Head on 9 November 1862. Private Edward Frederick lasted a short while longer, but succumbed to the post-surgical complication of brain fever on 16 February 1863 at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas, Florida. Other wounded men ultimately rallied, including Privates Manoah J. Carl, Jacob F. Hertzog, Frederick Knell, Samuel Kunfer, Samuel Reinert, John Schimpf, William Schrank, and Paul Strauss. Meanwhile, the command vacancy created when Captain Junker fell in battle was filled immediately by First Lieutenant Charles W. Abbott.

On 23 October, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers returned to Hilton Head, where several members of the regiment were assigned to serve on the funeral guard for Major-General Ormsby M. Mitchel, who had succumbed to yellow fever on 30 October. Ordered back to Key West on 15 November 1862, they would spend much of 1863 garrisoning federal installations in Florida as part of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps, Department of the South.

1863

Fort Jefferson, Dry Torguas, Florida (interior, circa 1934, C. E. Peterson, photographer, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

As Christmas came and went and the New Year dawned, First Sergeant Conrad Volkenand joined his fellow K Company soldiers and the men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies D, F, and H in garrisoning Fort Jefferson in the remote Dry Tortugas area of Florida (under the command of Lieutenant Colonel George Warren Alexander) while the men from Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I continued to guard Key West’s Fort Taylor (under the Command of Colonel Tilghman Good).

1864

On 25 February 1864, First Sergeant Conrad Volkenand and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians set off for a phase of service in which their regiment would truly make history. Steaming for New Orleans aboard the Charles Thomas, the members of the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies B, C, D, I, and K arrived at Algiers, Louisiana on 28 February, followed by the members of Companies E, F, G, and H on 1 March. (Finishing up a detached duty assignment in Florida, members of Company A did not arrive in Louisiana until 23 March, at which point they were assigned to additional detached duties. They did not reconnect with their regiment until April.)

Transported next by train to Brashear City (now Morgan City) and then by steamer to Franklin via the Bayou Teche, the 47th joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of U.S. the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, becoming the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign spearheaded by Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks.

From 14-26 March, the 47th passed through New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington while en route to Alexandria and Natchitoches. Often short on food and water, the regiment encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day, marching until mid-afternoon.

Marching until mid-afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvanians were then rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division. Sixty members of the 47th were cut down on 8 April during the volley of fire unleashed during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (Mansfield). The fighting waned only when darkness fell. The exhausted, but uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded and the dead. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill. Company K’s Second Lieutenant Alfred P. Swoyer was one of those killed in action at Mansfield.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate Major-General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner and son of Zachary Taylor, former president of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault during what has since become known as the Battle of Pleasant Hill.

Once again, casualties were severe with multiple members of the regiment killed, severely wounded or reported as missing in action. Still others were captured by Confederate troops. Held initially as prisoners of war at Pleasant Hill and Mansfield, Louisiana or at the CSA hospital at Shreveport, they were subsequently marched roughly one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford, a Confederate Army prison camp near Tyler, Texas, and held there as POWs until released during prisoner exchanges from July through November. (Sadly, at least three members of the 47th never made it out alive.)

Meanwhile, as the captured 47th Pennsylvanians were being spirited away to Camp Ford, their comrades were carrying out orders from senior Union Army leaders to head for Grand Ecore, Louisiana. Encamped there from 11-22 April, they engaged in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications.

They then moved back to Natchitoches Parish on 22 April. While en route, they were attacked again, this time, at the rear of their retreating brigade, but they were able to end the encounter quickly and move on to reach Cloutierville at 10 p.m. that same night (after a forty-five-mile march).

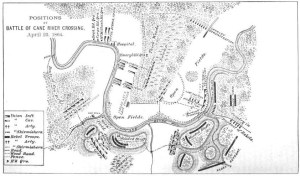

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were stationed just to the left of the “Thick Woods” with Emory’s 2nd Brigade, 1st Division as shown on this map of Union troop positions for the Battle of Cane River Crossing at Monett’s Ferry, Louisiana, 23 April 1864 (Major-General Nathaniel Banks’ official Red River Campaign Report, public domain).

The next morning (23 April), episodic skirmishing quickly roared into the flames of a robust fight. As part of the advance party led by Union Brigadier-General William Emory, the 47th Pennsylvanians took on the Confederate cavalry of Brigadier-General Hamilton P. Bee in the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry” or the “Cane River Crossing”).

Responding to a barrage from the Confederate artillery’s twenty-pound Parrott guns and raking fire from enemy troops positioned near a bayou and atop a bluff, Brigadier-General Emory directed one of his brigades to keep Bee’s Confederates busy while sending two other brigades to find a safe spot for the Union force to cross the Cane River. As part of the “beekeepers,” the 47th Pennsylvania supported Emory’s artillery.

Meanwhile, additional troops under Smith’s command, attacked Bee’s flank to force a Rebel retreat, and then erected a series of pontoon bridges that enabled the 47th Pennsylvania and other Union troops to make the Cane River Crossing by the next day. As the Confederates retreated, they torched their own food stores, as well as the cotton supplies of their fellow southerners. In a letter penned from Morganza, C Company’s Henry Wharton described what had happened:

Our sojourn at Grand Ecore was for eleven days, during which time our position was well fortified by entrenchments for a length of five miles, made of heavy logs, five feet high and six feet wide, filled in with dirt. In front of this, trees were felled for a distance of two hundred yards, so that if the enemy attacked we had an open space before us which would enable our forces to repel them and follow if necessary. But our labor seemed to the men as useless, for on the morning of 22d April, the army abandoned these works and started for Alexandria. From our scouts it was ascertained that the enemy had passed some miles to our left with the intention of making a stand against our right at Bayou Cane, where there is a high bluff and dense woods, and at the same attack Smith’s forces who were bringing up the rear. This first day was a hard one on the boys, for at 10 o’clock at night they made Cloutierville, a distance of forty-five miles. On that day the rear was attacked which caused our forces to reverse their front and form in line of battle, expecting too, to go back to the relief of Smith, but he needed no assistance, sending word to the front that he had ‘whipped them, and could do it again.’ It was well that Banks made so long a march on that day, for on the next we found the enemy prepared to carry out their design of attacking us front and rear. Skirmishing commenced early in the morning and as our columns advanced he fell back towards the bayou, when we soon discovered the position of their batteries on the bluff. There was then an artillery duel by the smaller pieces, and some sharp fighting by the cavalry, when the ‘mule battery,’ twenty pound Parrott guns opened a heavy fire, which soon dislodged them, forcing the chivalry to flee in a manner not at all suitable to their boasted courage. Before this one cavalry, the 3d Brigade of the 1st Div., and Birges’ brigade of the second, had crossed the bayou and were doing good service, which, with the other work, made the enemy show their heels. The 3d brigade done some daring deeds in this fight, as also did the cavalry. In one instance the 3d charged up a hill almost perpendicular, driving the enemy back by the bayonet without firing a gun. The woods on this bluff was so thick that the cavalry had to dismount and fight on foot. During the whole of the day, our brigade, the 2d, was supporting artillery, under fire all the time, and could not give Mr. Reb a return shot.

While we were fighting in front, Smith was engaged some miles in the rear, but he done his part well and drove them back. The rebel commanders thought by attacking us in the rear, and having a large face on the bluffs, they would be able to capture our train and take us all prisoners, but in this they were mistaken, for our march was so rapid that we were on them before they had thrown up the necessary earthworks. Besides they underrated the amount of our artillery, calculating from the number engaged at Pleasant Hill. The rebels say ‘it seems as though the Yankees manufacture, on short notice, artillery to order, and the men are furnished with wings when they wish to make a certain point.’

The damage done to the Confederate cause by the burning of cotton was immense. On the night of the 22d our route was lighted up for miles and millions of dollars worth of this production was destroyed. This loss will be felt more by Davis & Co., than several defeats in this region, for the basis of the loan in England was on the cotton in Louisiana.

After the rebels had fled from the bluff the negro troops put down the pontoons, and by ten that night we were six miles beyond the bayou safely encamped. The next morning we moved forward and in two days were in Alexandria. Johnnys followed Smith’s forces, keeping out of range of his guns, except when he had gained the eminence across the bayou, when he punished them (the rebs) severely.

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” in reference to Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, the Union officer overseeing its construction, this timber dam built near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 facilitated Union gunboat passage on the Red River (public domain).

Having finally reached Alexandria on 26 April, they learned they would remain at their latest new camp for at least two weeks. Placed temporarily under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, they were assigned yet again to the hard labor of construction work, helping to erect “Bailey’s Dam,” a timber structure that was designed to enable Union Navy gunboats to safely navigate the fluctuating waters of the Red River. According to Wharton:

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gun boats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people will eat), so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the iron clads down the river. After a great deal of labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic, chute], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’ The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gun boat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

Continuing their march, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers headed toward Avoyelles Parish. According to Wharton:

On Sunday, May 15th, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of the Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad where with the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. – We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed in line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired, and we advanced ’till dark, when the forces halted for the night with orders to rest on their arms. – ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee.

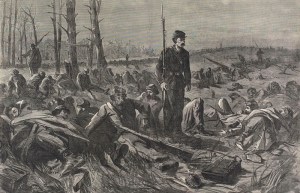

“Sleeping on Their Arms” by Winslow Homer (Harper’s Weekly, 21 May 1864).

“Resting on their arms,” (half-dozing, without pitching their tents, and with their rifles right beside them), they were now positioned just outside of Marksville, on the eve of the 16 May 1864 Battle of Mansura, which unfolded as follows, according to Wharton:

Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, they reached Missoula [sic, Mansura], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic, maneuvering] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic, were] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain correctly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport [sic, Simmesport] on the Achafalaya [sic, Atchafalaya] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over. – The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of the army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic, there] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.

Union Army base at Morganza Bend, Louisiana, circa 1863-1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Continuing on, the surviving members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry marched for Simmesport and then Morganza, where they made camp again. While encamped there, the nine formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the regiment in Beaufort, South Carolina (October 1862) and Natchitoches, Louisiana (April 1864) were officially mustered into the regiment between 20-24 June 1864.

The regiment then moved on and arrived in New Orleans in late June. On 4 July, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers received orders to return to the East Coast. Three days later, they began loading their men onto ships, a process that unfolded in two stages. Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I boarded the U.S. Steamer McClellan on 7 July and steamed away that day, while the members of Companies B, G and K remained behind, awaiting transport. (The latter group subsequently departed aboard the Blackstone, weighing anchor and sailing forth at the end of that month.)

As a result of this twist of fate, the 47th Pennsylvania’s “early travelers” had the good fortune to have a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln on 12 July 1864. They then took part in the mid-July Battle of Cool Spring near Snicker’s Gap, Virginia.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Halltown Ridge, looking west with “old ruin of 123 on left. Colored people’s shanty right,” where Union troops entrenched after Major-General Philip Sheridan took command of the Middle Military Division, 7 August 1864 (photo/caption: Thomas Dwight Biscoe, 2 August 1884, courtesy of Southern Methodist University).

Attached to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah beginning in August, the now fully-staffed 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was assigned to defensive duties in and around Halltown, Virginia in early August, and also engaged over the next several weeks in a series of back-and-forth movements between Halltown, Berryville and other locations within the vicinity (Middletown, Charlestown and Winchester) as part of a “mimic war” being waged by Sheridan’s Union forces with those commanded by Confederate Lieutenant-General Jubal Early. The 47th Pennsylvania then engaged in its next major encounter during the Battle of Berryville, Virginia from 3-4 September.

But, as Sheridan’s campaign was ramping up, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was also undergoing a major transformation as multiple officers and enlisted men mustered out at Berryville, Virginia upon expiration of their three-year terms of service. Among those departing on 18 September 1864 were the captains of Companies D, E and F, and First Sergeant Conrad Volkenand of Company K.

Return to Civilian Life

Following his honorable discharge from the military, Conrad Volkenand returned home to Pennsylvania where, in 1865, he wed Catherina Elisabeth Ringleben (1847-1890). A native of Philadelphia who had been born on 20 February 1847, she was a daughter of Andrew Ringleben (1817-1873) and Mary E. (Wagner) Ringleben (1832-1898), a native of Hessen, Germany.

He also launched his business career around this same time, opening a saloon business in Luzerne County. Daughter Anna Gertrude then opened her eyes for the first time at their home in Hazleton sometime around 1866. Three years later, on 11 May 1869, he joined his local chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic (Robison Post No. 20) — an organization he would continue to actively support for the remainder of his life.

Still operating his restaurant and saloon in Hazleton by 1870, he continued to reside in that borough with his wife and daughter Anna G. Volkenand. His real and personal estate holdings were valued at nine thousand five hundred dollars. He also founded the National Rifles in Hazleton that same year, and was commissioned as captain on 22 March 1870 (and then later as major — a title he would hold for the remainder of his life). Under his leadership, this local militia organization also became a unit, on 10 June 1870, of the Pennsylvania National Guard’s 9th Division.

Five years later, on 30 March 1875, he applied for a U.S. Passport. Confirming for the record that he had been born in “Widdershausen” on 20 December 1839, he also noted that he was married to twenty-nine-year-old Catherine Elisabeth, that they had a nine-year-old daughter named Anna Gertrude, and that he was thirty-five years old and five feet, eleven and one-half inches tall with brown hair, hazel eyes, a fair complexion, and a medium-sized nose, mouth and chin.

By 1880, the federal census taker in his Hazleton neighborhood documented that he was the operator of a hotel and saloon business at 37-39 East Broad Street, and that his household now included his wife, daughter, and Sophia Reinhold, a nineteen-year-old servant. Newspapers of the period also reported on his election by the general public to Hazleton’s borough council and, in 1880, as Luzerne County Recorder. Daughter Anna then wed Joseph McHale sometime mid-decade, and welcomed the birth of two sons — Conrad Joseph McHale circa 1887 and Joseph J. W. McHale on 3 July 1889.

But there were also moments of deep sadness. According to the 28 April 1888 edition of the Hazleton Plain Speaker:

Shortly before noon yesterday Catharine, the wife Ernst Lemmerhirt, and sister of Major C. J. and Andrew Volkenand, breathed her last at the family residence, on Church street, Diamond Addition, in the 51st year of her age. The deceased had been ill for some time and her recovery was not expected. The funeral will take place on Sunday afternoon, at 3 o’clock. Services will be held in Christ’s German Lutheran church by Rev. E. A. Bauer and interment will be made in the Vine street cemetery.

Two years later, the family then endured another tragedy with the on 26 January 1890 death of Joseph J. W. McHale (1889-1890), Conrad Volkenand’s youngest grandson. According to Hazleton Plain Speaker:

Joseph J. W. McHale, son of Anna and the late Joseph McHale, died at 3 o’clock yesterday afternoon at the residence of Major C. J. Volkenand, on East Broad street, aged 6 months and 21 days. The funeral will take place Sunday afternoon, at 2 o’clock. Services will be held in Christ German church by Rev. E. A. Bauer. Interment in the Vine street cemetery.

Illness, Death and Interment

Sometime around this same time, Conrad Volkenand also fell ill with Bright’s disease (chronic nephritis), a severe inflammation of the kidneys often associated with heart disease, and died at his home in Hazleton during the evening of 15 March 1890. Two days later, the Hazleton Plain Speaker then published the following tribute:

As a chronicler of passing events it becomes our duty this morning to announce the death of Major C. J. Volkenand, which occurred at his residence, on East Broad street, about half-past ten o’clock Saturday night, after an illness of five weeks with Bright’s disease of the kidneys, aged 50 years, 2 months and 25 days.

The deceased was born December 20, 1839, at Wiederhausen, Kurhessen, Germany. At the age of fifteen he came to this country and located at Tamaqua, where he learned the trade of a mason. He left there and went to Ashland. After a short residence in that place he came to Hazleton and lived here ever since. At the breaking out of the rebellion he enlisted in Company K., 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers, Capt. George Yunkers in command, which was mustered in at Allentown August 5, 1861. On September 17, of the same year, he was promoted to the rank of sergeant. He served with the company until the expiration of his term on September 18, 1864. He participated in many of the severest battles and it is said that he was as brave a soldier as ever enlisted. In 1865 he was married to Miss Catherine E. Ringleben, of town, who with one daughter, Annie, widow of the late Joseph H. McHale, and a little grandson in whom he was particularly interested, survive him. After he was married he engaged in the saloon business and has been ever since. On May 11, 1869, he was mustered in Robison Post, No. 20, G.A.R., and has been one of its most active members, having held several offices and at the time of his death was Past Commander of the Post.

In 1870 Mr. Volkenand organized the National Rifles in town and was made the captain of the company. His commission dated from March 22nd of that year. On the 10th of June the same year the company was attached to the National Guards of Pennsylvania, in the Brigade of the Ninth Division, composed of the uniformed militia of Columbia, Luzerne and Wyoming counties. Later he received his commission as Major.

In 1880 he was elected Recorder of this county and held the office three years. He also served as a member of the borough council for three years. He always took a deep interest in secret societies. He was a member of Encampment No. 27, Union Veteran Legion, Independent Order of Red Men, Good Brothers, Harugari, Knights of the Golden Eagle, the Mace and Lager, Royal Arcanum, and an honorary member of the Maennerchor and Concordia Singing Societies. Major Volkenand had in his possession a Testament which he prized very highly and always carried it with him. It was presented to him by the camp chaplain at Camp Griffin, Florida, November 12, 1861.

The deceased has a brother, A. F. Volkenand, and a sister, Mrs. Nicholas Eichler, who are residents of town. His father, a brother and two sisters are still in Germany. His father is quite old and is now in his eighty-first year.

The funeral will take place Wednesday afternoon at 2 o’clock. In accordance with a request made by him some time since it will be in charge of Robison Post and the dirge will be rendered by the Liberty Band. The services will be in Christ German church. A German and an English sermon will be preached. The remains will be interred in the Vine street cemetery.

Major Volkenand enjoyed a very large acquaintance and by his death another old soldier has answered the last roll call and fought his last battle.

The day after his interment at Hazleton’s Vine Street Cemetery during the afternoon of 19 March 1890, the same newspaper continued to honor his memory as it reported on his funeral services:

The funeral of the late Major C.J. Volkenand took place yesterday afternoon from the family residence, on East Broad street, and was one of the largest that has ever been seen in this town. The remains were laid to rest in a handsome and richly draped red cedar casket which was lined with a beautiful cream satin lining. The casket was trimmed with heavy copper and gold handles, with a name plate of same material, on which was engraved the name and age of the deceased. The floral offerings consisted of a wreath from the Ladies’ Auxiliary to Robison Post, and a pillow bearing the word ‘Father’ in blue immortelles. Short services were held at the house, and a selection was sung by the Concordia Singing Society, after which the funeral cortege proceeded in the following order to Christ German Lutheran church [now the Christ Evangelical Lutheran Church]: Kiowas Tribe, I.O. of R.M., Good Brothers Lodge, Harugari Lodge, Knights of the Golden Eagle and Commandery of the same Order, Concordia Singing Society and member of the Maennerchor, the Royal Arcanum, Union Veteran Legion, Hazleton Liberty Band and Robison Post, No. 20, G.A.R., where the pastor, Rev. E. A. Bauer, preached a German sermon, and Rev. John Wagner preached in English. The remains were interred in the Vine street cemetery. At the grave services were conducted by Robison Post, and at the conclusion the Red Men let a white dove fly over the grave, emblematic of the spirit taking its flight. The Liberty Band played a funeral dirge. All the societies of which the deceased was a member attended the funeral in a body.

His widow then followed him in death later that same year when she passed away in Danville, Montour County, Pennsylvania on 26 November 1890. The next day, the Hazleton Plain Speaker also reported on her passing:

Mrs. C. J. Volkenand, wife of the late Major Volkenand died at Danville on Tuesday evening. Her death was a surprise to her friends for it was expected she would finally recover. A telegram was received by H. W. Heidenriech, trustee for the estate, on Tuesday afternoon, informing him of Mrs. Volkenand’s serious illness. Yesterday morning, her daughter, Mrs. R. P. Reilly and Mr. Reilly left for Danville. They returned in the evening and brought the body with them. Deceased was a daughter of Mrs. Mary Ringleben and a sister to Mr. Andrew Ringleben, Mrs. Philip Keiper, Mrs. Charles Keiper and Mrs. Henry Schaffer. She was aged 44 years 9 months and 5 days, and was a native of Philadelphia. The funeral will take place to-morrow afternoon at 2 o’clock. Services in Christ German Lutheran Church, German and English. Interment in Vine street cemetery.

What Happened to Conrad Volkenand’s Daughter and Surviving Grandchildren?

After being widowed by her first husband sometime during the 1800s, Anna Gertrude (Volkenand) McHale, the only child of Conrad and Catherine Volkenand, remarried. United in marriage to Lansford, Pennsylvania native Robert P. Riley sometime around 1891, she and her second husband then welcomed the Hazleton birth of daughter Catharine E. Riley, who ultimately went on to wed Baltimore, Maryland native Nathan R. Butler (on 27 June 1922); after a long full life, she then passed away in Massachusetts on 5 October 1991.

Her step-brother, Conrad J. McHale, the other surviving grandchild of Conrad Volkenand, went on to become the chief accountant for The Lehigh Valley Coal Company’s Drifton Shops before accepting a position as an accountant with the Jeanesville Iron Works in Hazleton, Luzerne County.

Sources:

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Catherine Lemmerhirt (obituary of Conrad J. Volkenand’s sister). Hazleton, Pennsylvania: Hazleton Plain Speaker, 28 April 1888.

- “IrishandGermanImmigration,” in U.S. History Online Textbook. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Independence Hall Association, retrieved online 1 February 2018.

- Joseph J. W. McHale (obituary). Hazleton, Pennsylvania: Hazleton Plain Speaker, 25 January 1890.

- Major C. J. Volkenand, in History of Luzerne, Lackawanna and Wyoming Counties, PA, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of Their Prominent Men and Pioneers. New York, New York: W. W. Munsell & Co., 1880.

- Major C. J. Volkenand (obituary and funeral coverage). Hazleton, Pennsylvania: Hazleton Plain Speaker, 17 and 20 March 1890.

- McHale, Conrad J., Mary Hanlon, Joseph McHale and Anna (Volkenand) McHale, and Patrick H. and Ellen (Ferry) Hanlong; and Catherine E. Riley, Nathan R. Butler, Robert Riley, and Maiden Name of Wife’s Mother (Volkenand), in Marriage License Docket. Hazleton, Pennsylvania: Clerk of the Orphans’ Court, Luzerne County, 2 October 1918; 27 June 1922.

- Mrs. C. J. Volkenand (obituary). Hazleton, Pennsylvania: Hazleton Plain Speaker, 28 November 1890.

- Schmidt, Lewis G. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- U.S. Census. Washington, D.C. and Pennsylvania: 1870, 1880.

- Volkenand, C. J., Catherine Elisabeth Volkenand and Anna Gertrude Volkenand, in U.S. Passport Applications. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, 30 March 1875.

- Volkenwond [sic, Volkenand], Conrad J., in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

You must be logged in to post a comment.