The son of a German immigrant piano maker in Philadelphia and, later, a saloon keeper in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, G. Albert Hiller lived a life of change during an American era that was defined by the word “upheaval.”

Formative Years

Born as Gottlieb Albard Hiller in Pennsylvania on 19 April 1847, and baptized at the St. Michaels and Zion Lutheran Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on 23 May 1847, first-generation American G. Albert Hiller was a son of Gottlieb Heinrich Hiller (1812-1887) and Maria Barbara (Braun) Hiller (1815-1886), who were both natives of Baden-Württemberg (now part of Germany).

In 1850, Albert Hiller resided in Philadelphia with his parents and older brother Henry (1844-1903), who had been born as Johann Heinrich Hiller in June 1844 and was baptized at Saint Michael’s and Zion in Philadelphia in September. Their father’s occupation was documented by that year’s federal census as “piano maker.”

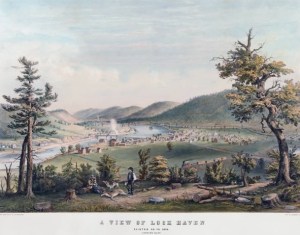

By 1853, Albert Hiller was living with his parents in Lock Haven, Clinton County, Pennsylvania, where his father (who was listed as Henry Hiller on the 1860 federal census) was employed as a saloon keeper. Residing with the family in 1860 were Albert’s younger siblings: Mary, who had been born as Maria Barbara Hiller on 29 May 1851, baptized at St. Michaels’s and Zion in Philadelphia on 9 November 1851, and later went on to marry Samuel Getz; William (1853-1928), who had been born as Robert William Hiller in Lock Haven on 26 November 1853; and Frederick Hiller (1854-1929), who had been born in Lock Haven in June 1854 and was known to family and friends as “Fred.” Also living with the family was Elizabeth Stork, a sixteen-year-old native of Hesse (now also part of Germany).

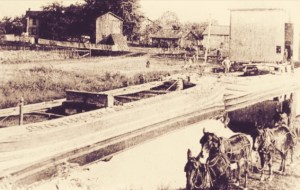

The Hillers had moved from a bustling city that was the fourth largest in the United States, with its population of more than one hundred and twenty-one thousand residents, to a small town of less than one thousand. Their new home was initially a hopeful one, though, because it was situated in a region of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania that had undergone significant transformation in response to a boom in area logging and lumber operations, a steady growth in traffic of the West Branch Canal that had opened in 1834, and the 1859 extension to Lock Haven of the Sunbury and Erie Railroad (known by 1861 as the Philadelphia and Erie Railroad).

But all of that progress and prosperity was suddenly threatened when South Carolina seceded from the United States in December 1860–a dramatic move that inspired other states across America’s Deep South to follow suit, launching the nation into a disastrous period of discord and fear that colored the start of a New Year. On 10 January 1861, readers of The Centre Democrat newspaper woke to find an article urging them to “Stand By the Old Flag”:

In these troubled times men of indefinite opinions or weak faith are reliable to have their confidences in our political system shaken. The hour demands self-recollection and trustful recourse to our most sacred principles and traditions. True souls, imbued with the legitimate sentiments of the age, and worthy of the destiny appointed to the nation, will not flinch before the present trial; they will remind themselves that such exigencies are the discipline of good institutions, as of good men; that virtue and greatness, whether of states or of individual men, have few surer indications than steadfastness to principle; that is to say confidence in principle when adversity most menaces it.

Never has there been an hour in which the citizens of these Free States should have stood more manfully around the flag which symbolizes their principles and their history, than they should in this period of trial. It is the testing time of our destiny; if found faithful and worthy, that flag will yet wave more proudly than ever before the eyes of the world. We must show our regard for it by all possible dispositions by compromise and conciliation, but not by one concession of the principles of political truth, righteousness and liberty, essential to the genius and mission of the nation….

These great Free States, charged with a solemn amenability to the opinion of the civilized world, and to the God of nations, cannot give way at this point. To do so would be to show a moral feebleness unworthy of their country and dishonorable to the human race. They could not give a surer proof of the political ennervation of the nation–of the extinction of the spirit of its founders, and of its best hopes. Such an example would be pointed to as a stronger demonstration of the failure of our political system than any local disruption of the Union, for it would prove not merely political perplexity, but radical demoralization.

We must, then, stand by our flag, by standing firmly on the position here indicated. Standing here, we shall not only be faithful to the spirit and design of the Constitution and its founders, but we shall be mighty in our national morale; we shall maintain our self-respect and dignity, and if calamities are to be confronted, we we can meet them as true men. Let us not distrust, in this testing hour, our destiny or the great principles upon which divine Providence has projected it. Let us away with even doubtful language respecting the “republican experiment.” No American artisan, among his children at his hearth, no farmer in his cottage, no teacher at the public desk, should allow the utterance of such treason to his fathers, and to the hopes of mankind; it is fit only for unprincipled demagogues who can sacrifice the public good for their individual hopes.

Whatever may be the result of the southern secession, these Free States are sufficient to continue, with but a transient disturbance, a mighty and invincible government of free and sovereign men; they could at once, with the loss of all the disaffected States, be a first rate power among the nations … their granaries feeding the world, their commerce in all its ports, and their old and honored flag, the emblem of successful self-government, before the eyes of all nations.–Without the seceding States, they would be still as great as the Roman empire in its greatest glory….

…. We have contented for conciliation–we still contend for it–we shall use every honorable means toward it; but if fail it must, let us accept with self-respect, and with unabated fidelity to our country and the world, the mournful alternative. Our States and our homes will remain safe and prosperous, not withstanding some temporary disturbance. The unavoidable doom of such recreancy to the work of our founders will fall elsewhere, and will give a lesson to the world, in contrast with our own steadfast example, which may fortify rather than impair the principles of constitutional free government….

Mississippi, Florida and Alabama (9-11 January 1861). Georgia (19 January). Louisiana (26 January). Texas (1 February). One terrible week after another, the United States of America fell further into disunion.

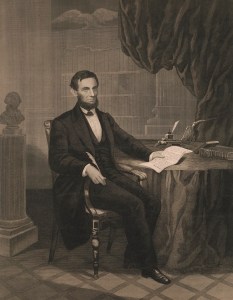

And then Fort Sumter fell to Confederate States Army troops on 13 April 1861. In response, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation two days later, calling for seventy-five thousand volunteer soldiers to help defend the nation’s capital and end the secession crisis.

The American Civil War

The U.S. Capitol Building, unfinished at the time of President Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration, was still not completed when the first of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers arrived in Washington, D.C. in September 1861 (public domain).

On 17 April, the secession crisis deepened when Virginia seceded from the United States, followed by Arkansas (6 May), North Carolina (20 May) and Tennessee (8 June). Just over six weeks later, Albert Hiller and other Lock Haven residents were buoyed by news reports that Union troops had beaten the Confederate States Army in the First Battle of Bull Run — the first major battle of the American Civil War — only to learn later that the Union Army had, in reality, been soundly defeated during the bloody encounter on 21 July 1861. By September, The Centre Democrat was referring to Bull Run as a “lamentable disaster.”

1862

U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stantion, circa 1862-1865 (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

As the American Civil War persisted into a new calendar year, Edwin M. Stanton made news headlines across the nation with his United States Senate confirmation as the new U.S. Secretary of War. According to historians at Dickinson College, “his appointment was generally welcomed as a cementing of Northern unity.” Thirty-six senators supported his confirmation; two opposed it. In response, The Watchman, Lock Haven’s Democratic-leaning newspaper, advised its readers that “The retreat of Mr. Cameron [Simon Cameron] and the appointment of so able and conservative a successor as Edwin M. Stanton will impart hope to the country.”

That day’s edition of The Watchman also reported that the federal government’s projected war-time expenditures for the current fiscal year would be staggering, with more than three hundred and sixty million dollars likely to be spent on the just the operations of the Union Army alone. Later that same month, the Union Navy flexed its muscles with its launch of a technological marvel — the famed ironclad known as the USS Monitor.

On 22 February, Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as the first president of the Confederate States of America. Lock Haven’s Watchman newspaper published a two-paragraph response in its 6 March 1862 edition:

Jefferson Davis was inaugurated permanent President of the Southern Confederacy, on Saturday, the 22d ult., at Richmond. It is said that there was not the least enthusiasm; in fact, that the affair was of a rather gloomy nature….

Mr. Davis has been sworn into office for six years. Whether he will be allowed to fill out his term, time alone will tell. From present appearances, it is highly probable that his presidency will not last six months.

President Abraham Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862 (W. E. Winner, painter, J. Serz, engraver, circa 1864; public domain, U.S. Library of Congress).

That same day (6 March 1862), President Abraham Lincoln recommended to the U.S. Congress that the United States government “cooperate with any State which may adopt gradual abolishment of slavery, giving to such State pecuniary aid, to be used by such State, in its discretion, to compensate for the inconveniences, public and private, produced by such change of system.” If members of Congress agreed, he added, “the States and people immediately interested should be at once distinctly notified of the fact, so that they may begin to consider whether to accept or reject it.”

The Federal Government would find its highest interest in such a measure, as one of the most efficient means of self-preservation. The leaders of the existing insurrection entertain the hope that this Government will ultimately be forced to acknowledge the independence of some part of the disaffected region, and that all the slave States north of such part will then say, ‘The Union for which we have struggled being already gone, we now choose to go with the Southern section.’ To deprive them of this hope substantially ends the rebellion, and the initiation of emancipation completely deprives them of it as to all the States initiating it. The point is not that all the States tolerating slavery would very soon, if at all, initiate emancipation: but that while the offer is equally made to all, the more northern shall by such initiation make it certain to the more southern that in no event will the former ever join the latter in their proposed confederacy.…

On 16 April 1862, slavery was abolished in the District of Columbia when President Lincoln signed “An Act for the release of certain persons held to service or labor in the District of Columbia.” Passed by the U.S. Senate on 3 April and the U.S. House on 12 April, the legislation freed more than three thousand men, women and children. Offering each person freed one hundred dollars if they chose to leave the United States, the new law also paid former slaveowners three hundred dollars “for each individual they had legally owned,” according to District of Columbia historians.

Just over a month later, President Lincoln approved another historic piece of legislation — one that would dramatically reshape the population of the United States. On 21 May 1862, he signed, “An Act to secure homesteads to actual settlers on the public domain.” Known today as the Homestead Act of 1862, it encouraged a massive migration of United States residents to western states and territories by offering one hundred and sixty acres of land to anyone who had never borne arms against the U.S. government, and who was twenty-one years of age or older and was a U.S. citizen (or had filed an application to become a naturalized citizen). Even women were eligible to obtain land under this legislation if they were single, widowed or divorced, or had been deserted by their husbands.

And only a minimal filing fee was required to obtain the title to that sought-after, “undeveloped land” — roughly two hundred and seventy million acres that were, in reality, tribal lands where Native Americans were already living. It was subsequently touted as a “Triumph of Free Homes” by Pennsylvania’s Bradford Reporter and as “Land for the Landless” by Galusha A. Grow, Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.

On 1 June, Confederate General Robert E. assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia. Eighteen days later, President Lincoln signed legislation outlawing slavery in the Western Territories held by the United States. He then presented the Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet on 22 July.

By early September, Albert Hiller and other Lock Haven residents were reading the shocking news that nearly twenty-two thousand men had become casualties during the Second Battle of Bull Run, which had been waged from 28-30 August 1862. The federal government’s final figures would ultimately show that the Union had suffered a casualty rate that was nearly double what had been inflicted on the Confederacy.

And then came Antietam, “the deadliest one-day battle in American history,” according to the American Battlefield Trust. On 3 October, The Central Press gave its readers in Bellefonte and Lock Haven the opportunity to read the report penned by Union Major-General George B. McClellan regarding the actions and outcomes in Maryland at South Mountain and Antietam on 14 and 17 September which resulted in more than twenty-seven thousand additional casualties. The most striking of his comments, perhaps, was the sentence, “We have not lost a single gun or color.”

Another one thousand men here. Another five thousand men there. One skirmish or engagement with the enemy after another throughout October and November, followed by the Battle of Fredericksburg that was waged in Virginia from 11-15 December 1862. “With nearly 200,000 combatants–the greatest number of any Civil War engagement,” according to the American Battlefield Trust, it “was one of the largest and deadliest battles of the Civil War,” and “featured the first opposed river crossing in American military history as well as the Civil War’s first instance of urban combat.”

The war was now being brought to the front doors of American homes across the South.

Meanwhile, the newspapers read by the Hiller family and other Clinton County residents were filled with letters from soldiers who hailed from Lock Haven, interspersed with news of the grand opening of an ice cream parlor and construction of a new hotel, as well as the amounts of financial assistance being paid weekly to hundreds of area women and children by the Clinton County Board of Relief in November and the spread of diphtheria across the county in December.

1863 — 1864

The year of 1863 began hopefully as the United States America took a decisive step toward the fulfillment of its most cherished principle — that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” — with President Abraham Lincoln’s New Year’s Day announcement of the nation’s Emancipation Proclamation. in which he declared that “all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free.”

On 3 March, President Lincoln signed the Enrollment Act of 1863 into law, establishing the first federal military draft in the history of the United States. It required that every white male citizen of the United States between the ages of twenty and forty-five, and every white male immigrant who had applied for citizenship and was within that same age bracket, register for federal military service, but it also allowed men with the financial means to hire substitutes to serve for them in order to avoid being drafted.

Six weeks later, on 19 April 1863, Albert Hiller turned sixteen. Still too young to join the Union Army, he remained at home with his parents, watching as older friends and neighbors from Lock Haven headed off to war.

But from 30 April to 6 May, the Union Army was once again battered by Confederate forces. Engaged in the Battle of Chancellorsville, Virginia, it wracked up more than seventeen thousand casualties during a loss in which the Confederates shook off the killing or injury of more than thirteen thousand of its men. In response, Bellefonte’s Daily Watchman asked its readers, “Are We a Civilized People?”

We are shocked by the horrors each day unfolds. This war seems to have degenerated into a mere strife of the vilest passions–burning, killing, destroying, annihilation–instead of the honorable combat which teaches us to respect private property, protect women and children, and do no more destruction than necessity requires….

What good does it do? When Hooker is defeated at Chancellorsville, what does he gain by destroying the enemy’s agricultural implements? When Hunter cannot take Charleston, how will cutting down trees and breaking dykes aid him? When Banks is repulsed at Port Hudson, will a long string of captured negroes and stolen property shield him from disgrace? Are we to allow such things as these to be held up to us as war–as just, necessary, civilized warfare? [….]

It is time that these thieving, murdering expeditions were stopped….

And then the war arrived on the doorsteps of Keystone State residents. Commanded by General Robert E. Lee, three corps of Confederate States Army soldiers crossed the border into the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in late June. Searching for, and confiscating supplies from local residents as they marched toward the town of Gettysburg, they came face to face with Union Cavalrymen commanded by Brigadier-General John S. Buford who are then reinforced by the Union Army’s 1st and 11th Corps, led by Major-General John F. Reynolds. That encounter sparked the flames of the tide-turning, three-day Battle of Gettysburg, involving more than one hundred and sixty-five thousand men. A decisive, but costly victory for the federal government, more than twenty-three thousand Union soldiers were dead or wounded, with the Lee’s Army drained by more than twenty-eight thousand casualties.

The Watchman noted in its 17 July edition that “A number of our citizens have just returned from viewing he battle-field at Gettysburg, and express themselves as much impressed by the scenes then presented by that bloody field.”

Numbers of dead men were yet unburied, and fragments of the battle were strewn in every direction. Dead horses were everywhere, and the stench is described as almost unbearable.–God save us from any more such awful scenes.

That prayer went unanswered, however, as one bloody battle after another was waged througout the remainder of the year and all of 1864, with Albert Hiller and his family, friends and neighbors reading increasingly shocking accounts of the war in their local newspapers in between their attempts to perform routine, daily tasks–all the while pretending that life was normal and good.

1865 — 1866

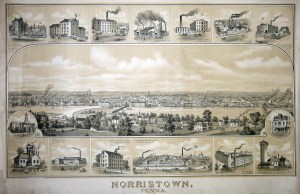

Having matured so much that he appeared to be old enough to enlist for military service during the American Civil War, Albert Hiller left home and headed for Norristown in Montgomery County, where he enrolled on 7 March 1865 for a one-year tour of duty with the Union Army. He then mustered in there that same day as a private with Company I of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Military records at the time indicated that he was a nineteen-year-old baker living in Pennsylvania who was five feet, seven inches tall with brown hair, gray eyes and a fair complexion. Records also show that he connected with his regiment at Camp Fairview near Charlestown, West Virginia from a recruiting depot on 14 March of that same year — just as the 47th Pennsylvania was preparing to head back to the Washington, D.C. area, by way of Winchester and Kernstown, Virginia.

In reality, he was a seventeen-year-old boy who would turn eighteen just over a month later. While he likely suspected that the regiment he was joining had seen combat, he may not have known that the 47th Pennsylvania was a genuinely battle-hardened regiment that had “come of age” in the bloody Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina in 1862, had made history during the Union’s Red River Campaign across Louisiana in 1864, and had then helped valiantly turn the war firmly in the Union’s favor during Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign later that same year.

His new job and that of his new comrades would, he thought, be the dogged pursuit and capture or killing of Confederate troops in order to end both the tragic war and the brutal practice of chattel slavery. In reality, their job was to prevent Confederate troops from invading Washington, D.C.

Joyous News and Then Tragedy

As April 1865 opened, the battles between the Army of the United States and the Confederate States Army intensified, finally reaching the decisive moment when the Confederate troops of General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox on 9 April.

The long war, it seemed, was finally over. Less than a week later, however, the fragile peace was threatened when an assassin’s bullet ended the life of President Abraham Lincoln. Shot while attending an evening performance of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre on 14 April 1865, he had died from his head wound at 7:22 a.m. the next morning.

Spectators gather for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, beside the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half-staff after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Shocked, and devastated by the news, which was received at their Fort Stevens encampment, Private Albert Hiller and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were given little time to mourn their beloved commander-in-chief before they were ordered to grab their weapons and move into the regiment’s assigned position, from which they helped to protect the nation’s capital and thwart any attempt by Confederate soldiers and their sympathizers to re-ignite the flames of civil war that had finally been stamped out.

So key was their assignment that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were not even allowed to march in the funeral procession of their slain leader. Instead, they took part in a memorial service with other members of their brigade that was officiated by the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental chaplain, the Reverend William D. C. Rodrock.

Present-day researchers who read letters sent by 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers to family and friends back home in Pennsylvania during this period, or post-war interviews conducted by newspaper reporters with veterans of the regiment in later years, will learn that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were collectively heartbroken by Lincoln’s death and deeply angry at those whose actions had culminated in his murder. Researchers will also learn that at least one member of the regiment, C Company Drummer Samuel Hunter Pyers, was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train, while other members of the regiment were assigned to guard duty at the prison where the key assassination conspirators were being held during the early days of their imprisonment and trial, which began on 9 May 1865.

During this phase of duty, the regiment was headquartered at Camp Brightwood.

Attached to Dwight’s Division of the 2nd Brigade of the U.S. Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers also participated in the Union’s Grand Review of the National Armies, which took place in Washington, D.C. on 23 May.

Helping a Shattered Nation Rebuild

Ruins of Charleston, South Carolina as seen from the Circular Church, 1865 (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

During their Reconstruction Era tour of America’s Deep South, Private Albert Hiller and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were initially stationed in Savannah, Georgia. Assigned to provost (military police) and other Reconstruction-related duties there in early June, as members of Dwight’s Division, 3rd Brigade, U.S. Department of the South, they were subsequently ordered to Charleston, South Carolina, where they were assigned to similar duties from early July through the remainder of the year.

Honorably mustered out with his regiment in Charleston on Christmas Day in 1865, Private Albert Hiller was transported north by ship with his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers to New York City, and then by train to Philadelphia, where he was given his honorable discharge papers at Camp Cadwalader in early January 1866.

Return to Civilian Life

Log rafts moved through the Susquehanna River’s west branch as they passed Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, circa 1880s (John W. C. Floyd, public domain; click to enlarge).

Sometime after his release from service with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, Albert Hiller enlisted with Company A of the Clinton County Infantry, which was a unit of the Pennsylvania National Guard. Military records at the time described him as a twenty-two-year-old resident of Lock Haven who was five feet, six inches tall with black hair, gray eyes and a dark complexion. Promoted to the rank of corporal in 1869, his military records noted that he worked as a clerk for his unit and that his last active record entry occurred that same year (indicating that he was likely honorably discharged in 1869).

Sometime around 1870, Albert Hiller’s younger sister wed baker Samuel Getz. By that year, Albert had also moved out of the Hiller family home and had become a boarder residing in the home of Jacob Brown, a fifty-year-old German immigrant who had become a merchant in Lock Haven. Still living as a boarder by mid-decade, Albert Hiller was documented by the 1874 Lock Haven city directory as one of the men who were employed as clerks that year.

Sometime before June 1880, Albert Hiller’s younger brother, Frederick Hiller also moved away. After relocating to Hazleton in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, he was employed as a tailor who lived as a boarder in the home of store clerk James Whitaker. While there, Fred met Leona M. James, a native of Hookset, New Hampshire who had also relocated to Hazleton. They were subsequently married in Manchester, New Hampshire on 28 August 1883.

As of 1 June 1880, however, Albert Hiller was working as a “dealer in hides” and had resumed life at his parents’ home in Lock Haven’s First Ward, where his father was now employed in the grocery business, according to that year’s federal census. Also residing there was Albert’s brother William, who worked as a plasterer.

The Hiller siblings were subsequently preceded in death by both of their parents. Their mother, who had passed away in Lock Haven on 27 March 1886, was buried at that community’s Highland Cemetery. Their father, who had died in Lock Haven on 30 November 1887, was buried beside her.

From that point on, Albert Hiller’s life appears to have begun a downward spiral.

Mental Illness, Death and Interment

A simple, average index card found in the archives of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s Department of Military Affairs provides only the barebones facts of Albert Hiller’s life history. Born in 1840 [sic, 1847], he served in the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ I Company from 7 March to 25 December 1865, died on 7 December 1888, and was buried in grave no. 42 in section C, lot no. 122 of the Highland Cemetery in Lock Haven Clinton County, Pennsylvania. His grave was then marked with a family headstone that was made of marble.

That index card, however, does not provide answers as to why his life was such a short one. According to The Centre Democrat newspaper, his final moments were troubling:

Albert Hiller, a well known citizen of Lock Haven, committed suicide by hanging at his residence on East Water street last Thursday night. Mr. Hiller’s dead body was discovered by John Demas, who resides in part of the same house in which Mr. Hiller lived. The body was found hanging in the closet, and suspended by a small rope one end of which was tied to the rafter of the closet roof and the other end looped about the dead man’s neck. His feet touched the floor and his knees were slightly bent forward. Mr. Demas visited the closet and saw the body hanging but did not recognize it as that of any one he knew. He went to Hiller’s door and rapped, but getting no answer opened the door and found that the lamp was burning, but Hiller’s bed was vacant. He then aroused the neighbors who upon examination found the body to be that of Albert Hiller. Coroner Mader was notified at once who empanelled a jury to inquire into the cause of his death. The jury rendered a verdict in accordance with the facts that the deceased came to his death by hanging with his own hands. The deceased was a veteran soldier in the late war, having served in Company I, 47th Regiment Pa. Vols. He was also a member of John S. Bittner Post, G.A.R. No cause is known why he should have committed the rash act.

Private Albert Hiller was subsequently laid to rest at the Highland Cemetery in Lock Haven. Still unmarried at the time of his death, he was survived by his siblings Henry, Mary, William, and Fred.

What Happened to His Surviving Siblings?

Albert Hiller’s brother, John Henry Hiller was employed as a watchman in Camden, New Jersey after the turn of the century. He died at the age of fifty-nine in Atlantic City, New Jersey on 16 December 1903 and was laid to rest at the Monument Cemetery in Philadelphia on 19 December.

The story of Albert Hiller’s sister, Mary Barbara (Hiller) Getz, was, perhaps, equally as tragic as his own. After appearing to live a largely successful life with her husband, cake baker Samuel Getz, during which time she gave birth to eight children (six of whom survived), she was widowed by him in 1910 and subsequently fell into poverty. Forced by her circumstances to move into the Northampton County Almshouse in Upper Nazareth Township in 1917, she was sickened by “the grippe” (the flu). As her condition declined, she also developed pneumonia and died at the almshouse on 19 April 1921. Buried beside her husband at the Nisky Hill Cemetery in Bethlehem, she was survived by her children: Albert Getz, a resident of Bethlehem who worked for H. A. Clewell, a fish and oyster merchant; William Getz, a resident of Easton who was employed as a painter; Fred Getz, a Spanish-American War veteran and resident of Fullerton who worked for the Keystone Granite Quarry; and Helen (Getz) Davidson, who had previously wed farmer Samuel Davidson and lived near Bushkill Park.

* Note: Albert Getz (1889-1931), a son of Mary (Hiller) Getz and Albert Hiller’s namesake (but who was known to family and friends as “John Getz”), also died tragically. While waiting for the arrival of a trolley car in Fountain Hill on 9 November 1931, he fell backwards and struck his head on the sidewalk. Rendered unconscious by the fall, he was picked up and carried to St. Luke’s Hospital by the Rev. M. S. Mumma and Merritt Metzler, who had been standing nearby and had witnessed the accident. Their rescue was a futile one, however; John Getz died en route, as a result of heart failure, according to the coroner.

Albert Hiller’s brothers, Robert William Hiller and Frederick Hiller, had far different outcomes, however; they both went on to live roughly forty more years after Albert’s tragic end.

Initially married to Jennie Elizabeth Goodman (1848-1902), R. William Hiller was subsequently widowed by her when she passed away in Lock Haven on 15 January 1902. He then remarried, taking as his second wife Emma Matilda Dietz (1861-1927), a first-generation American and Lock Haven native who was a daughter of John F. Dietz (1838-1885) and Regina (Scheid) Dietz (1840-1913). Widowed by his second wife when she died in Lock Haven on 14 January 1927, R. William Hiller then passed away the following year and was interred at the Highland Cemetery in Lock Haven.

A working tailor at the turn of the century, Fred Hiller resided with his wife, Leona (James) Hiller, at the Summerville, Georgia home of her parents, Charles and Pauline James. Also residing with them was Fred and Lorena’s seventeen-year-old son, James W. Hiller; Leona’s seventy-one-year-old uncle, Lemuel James; and Leona’s sister and brother-in-law, Cora (James) Ohl and Amos Ohl.

Still involved in the tailoring business as of 1910, Fred Hiller was living with his wife, son and widowed mother-in-law in Neptune Township in Monmouth County, New Jersey that year. But by 1920, his mother-in-law had passed on and he was head of a household that was composed of just father, mother and son, who was employed as a civil engineer.

Their lives changed forever in 1928, though, when Frederick Hiller died at the age of seventy at the family’s home in Avon, New Jersey. Following his passing on 28 January, he was subsequently laid to rest at the Glenwood Cemetery in West Long Branch, New Jersey.

Sources:

- “Abraham Lincoln: Message to Congress Recommending Compensated Emancipation,” in “The American Presidency Project.” Santa Barbara, California: University of California, Santa Barbara, retrieved online 12 December 2024.

- “Are We a Civilized People?” Bellefonte, Pennsylvania: The Democratic Watchman, 3 July 1863.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- “Bethlehem Man Passes Away Suddenly” (accident and death report about Albert Hiller’s nephew, John Getz). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 10 November 1931.

- Brown, Jacob, Margaret, Caroline, B. F., James, and Elizabeth; Berger, Peter; and Hiller, Albert, in U.S. Census (Lock Haven, Second Ward, Clinton County, Pennsylvania, 1870). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Death Notice” (obituary of Albert Hiller’s brother, Frederick Hiller). Asbury Park, New Jersey: Asbury Park Evening Press, 29 January 1929.

- Emma M. Hiller (obituary of second wife of Albert Hiller’s brother, R. William Hiller). Lock Haven, Pennsylvania: The Clinton County Times, 21 January 1927.

- “Ending Slavery in the District of Columbia,” in “Emancipation Day.” District of Columbia: DC.gov, retrieved online 12 December 2024.

- Frederick Hiller (Albert Hiller’s brother) and Leona M. James, in Marriage Records (Manchester, New Hampshire, 28 August 1883). Manchester, New Hampshire, Office of the Town Clerk.

- “Frederick S. Getz, Spanish War Veteran” (obituary of Albert Hiller’s nephew). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 12 March 1952.

- “G. Albert Hiller of Lock Haven Hangs Himself with a Rope.” Bellefont, Pennsylvania: The Centre Democrat, 13 December 1888.

- Getz, Mary (sister of Albert Getz), in Death Certificates (file no.: 39349, registered no.: 46, date of death: 19 April 1921. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Getz, Samuel, Mary (wife of Samuel and sister of Albert Hiller), William, Frederick, and Mary (daughter), in U.S. Census (Allentown, Seventh Ward, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, 1880). Wa!shington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Gottlieb Albard Hiller (son), Gottlieb Heinrich Hiller (father) and Maria Barbara (Braun) Hiller, in Baptismal Records (23 May 1847). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: St. Michael’s and Zion Lutheran Church.

- Hiller, Albert, in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 (Company I, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Hiller, Albert, in Records of Burial Places of Veterans (Highland Cemetery, Lock Haven, Clinton County, Pennsylvania. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Hiller, Fred, Leona and James, in U.S. Census (Neptune Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey, 1920). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Hiller, Frederick (Albert Hiller’s brother), Leona and James; and James, Paulina, in U.S. Census (Neptune Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey, 1910). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Hiller, Gottlieb, Barbara, Albert, and William, in U.S. Census (Lock Haven, First Ward, Clinton County, Pennsylvania, 1880).Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Hiller, Henry, Barbara, Albert, Mary, William, and Fred; and Stork, Elizabeth, in U.S. Census (Lock Haven, Clinton County, Pennsylvania, 1860). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Hiller, John Henry, in Death and Burial Records (City of Philadelphia, 16 and 19 December 1903). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: City Archives, Department of Records, City of Philadelphia.

- “Inauguration of Jefferson Davis.” Lock Haven, Pennsylvania: The Watchman, 6 March 1862.

- James, Charles, Pauline and Lemuel; Hiller, Fred (Albert Hiller’s brother), Leona and James; and Ohl, Amos and Cora, in U.S. Census (Summerville, 1269 Militia District, Georgia, 1900). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Johann Heinrich Hiller (son), Gottlieb Heinrich Hiller (father) and Maria Barbara (Braun) Hiller, in Baptismal Records (8 September 1854). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: St. Michael’s and Zion Lutheran Church.

- Maria Barbara Hiller (daughter), Gottlieb Heinrich Hiller (father) and Maria Barbara (Braun) Hiller, in Baptismal Records (9 November 1851). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: St. Michael’s and Zion Lutheran Church.

- Maynard, D.S. Historical View of Clinton County from Its Earliest Settlements to the Present Time. Lock Haven, Pennsylvania: The Enterprise Printing House, 1875.

- “Mrs. Mary Getz” (death notice of Albert Hiller’s sister, Mary). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 22 April 1921.

- “Philadelphia Population History.” Boston, Massachusetts: Boston University, retrieved online 10 December 2024.

- “Roster of the 47th P. V. Inf.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 26 October 1930.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- “Secretary of War.” Lock Haven, Pennsylvania: The Centre Democrat, 12 September 1862.

- “Stand By the Old Flag.” Lock Haven, Pennsylvania: The Centre Democrat, 10 January 1861.

- “The Change in the Cabinet.” Lock Haven, Pennsylvania: The Watchman, 23 January 1862.

- “The News: Official Report of the Late Battles.” Bellefonte, Pennsylvania: The Central Press, 3 October 1862.

- “Triumph of Free Homes.” Towanda, Pennsylvania: Bradford Reporter, 29 May 1862.

- Whitaker, James, Harriet, Alice, Ella, and Oliver; Horn, Sarah; and Hiller, Fred (Albert Hiller’s brother), in U.S. Census (Borough of Hazleton, 193rd District, West Ward, Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, 1880). Washington, D.C.: U.S.National Archives and Records Administration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.