Very little is presently known about the formative years of this particular 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer, save for the fact that he was born on 27 September 1827. What researchers do know is that he was born into a family of asthmatics — a condition that would also negatively impact his own health as he entered his thirties.

His name was Charles A. Henry, and he worked as a blacksmith in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania during the mid to late nineteenth century.

American Civil War

On 4 September 1861, Charles A. Henry enrolled for military service in Allentown. He then officially mustered in for duty on 18 September 1861 at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County as a second lieutenant with Company G of the newly-formed 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Company G was initially led by Charles Mickley, a miller and merchant who was a native of Mickleys near Whitehall Township in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania. After recruiting the men who would form the 47th Pennsylvania’s G Company, Charles Mickley had personally mustered in for duty as a corporal with the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry on 18 September 1861, and was then promptly commissioned as a captain and given command of Company G that same day. Also on that day, Charles A. Henry was made Company G’s second lieutenant, and John J. Goebel was commissioned as G Company’s first lieutenant. The remainder of Company G — ninety-five men — also enrolled and mustered in that same day; by the next month, the roster numbered ninety-eight — a figure that would hold until 1862. By the time the Civil War ended in 1865, a total of one hundred and ninety-five men would ultimately serve with G Company.

Camp Curtin, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Harper’s Weekly, 13 December 1862, public domain; click to enlarge).

Following a brief light infantry training period at Camp Curtin, Captain Mickley and his company were sent by train with the 47th Pennsylvania to Washington, D.C., where they were stationed at “Camp Kalorama” on the Kalorama Heights near Georgetown, about two miles from the White House, beginning 21 September. Henry Wharton, a field musician (drummer) with the regiment’s C Company, penned an update the next day to his hometown newspaper, the Sunbury American:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September 1861] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so wrapt [sic] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on dis-covering they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.

Col. Good, who has command of our regiment, is an excellent man and a splendid soldier. He is a man of very few words, and is continually attending to his duties and the wants of the Regiment.

…. Our Regiment will now be put to hard work; such as drilling and the usual business of camp life, and the boys expect and hope for an occasional ‘pop’ at the enemy.

Chain Bridge across the Potomac above Georgetown looking toward Virginia, 1861 (The Illustrated London News, public domain).

On 24 September 1861, the members of Company G and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers officially mustered in with the U.S. Army. Three days later, on 27 September, a rainy, drill-free day which permitted many of the men to read or write letters home, the 47th Pennsylvanians were assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General Isaac Ingalls Stevens. By that afternoon, they were on the move again, headed for the Potomac River’s eastern side where, upon arriving at Camp Lyon in Maryland, they were ordered to march double-quick over a chain bridge and off toward Falls Church, Virginia.

Arriving at Camp Advance at dusk, the men pitched their tents in a deep ravine about two miles from the bridge they had just crossed, near a new federal military facility under construction (Fort Ethan Allen), which was also located near the headquarters of Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith (nicknamed “Baldy”), the commander of the Union’s massive Army of the Potomac (“Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Armed with Mississippi rifles supplied by the Keystone State, their job was to help defend the nation’s capital.

Once again, Company C Musician Henry Wharton recapped the regiment’s activities, noting, via his 29 September letter home to the Sunbury American, that the 47th had changed camps three times in three days:

On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this Camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders.)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march this morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic, Lewinsville], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six [sic] tons of hay. A very nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment….

The Big Chestnut Tree, Camp Griffin, Langley, Virginia, 1861 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Sometime during this phase of duty, as part of the 3rd Brigade, the 47th Pennsylvanians were moved to a site they initially christened “Camp Big Chestnut” in reference to the large chestnut tree located nearby. The site would eventually become known to the Keystone Staters as “Camp Griffin,” and was located roughly ten miles from Washington, D.C. While en route, according to historian Lewis Schmidt, “Pvt. Reuben Wetzel, a forty-six-year-old cook in Capt. Mickley’s Company G,” climbed up on a horse that was pulling his company’s wagon while his regiment was engaged in a march from Fort Ethan Allen to Camp Griffin (both in Virginia). When the regiment arrived at a deep ditch, “the horses lost their footing and the wagon overturned and plunged into the ditch, with ‘the old man, wagon, and horses, under everything.’”

Based on his review of military records, Schmidt believed that Pvt. Jacob H. Bowman (aged thirty-five), a former Allentown miller who was Company G’s designated wagon master, was likely the driver at the time of Private Wetzel’s accident. Although alive when pulled from the wreckage, Pvt. Wetzel had fractured a tibia, a serious injury even today. He succumbed to complications just five weeks later (on 17 November 1861) while being treated for the fracture and resulting amputation of his leg at the Union Hotel General Hospital in Georgetown, Washington, D.C. He was interred at Military Asylum Cemetery (now known as the U.S. Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home National Cemetery).

Pageantry and Hard Work

Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were engaged in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads on 11 October 1861. In a letter that was written to family back home around this same time, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin (the leader of C Company who would be promoted in 1864 to head the entire 47th Regiment) reported that companies D, A, C, F and I (the 47th Pennsylvania’s right wing) were ordered to picket duty after the left-wing companies (B, G, K, E, and H) had been forced to return to camp by Confederate troops. In his letter of 13 October, Henry Wharton described their duties, as well as their new home:

The location of our camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets. Last night, however, they (the Rebels) calculated wide of their mark; some of the New York 33d boys were out on picket; some fourteen or fifteen shots were exchanged, when our side succeeded in bringing to the dust, (or rather mud,) an officer and two privates of the enemy’s mounted pickets. The officer was shot by a Lieutenant in Company H [?], of the 33d.

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort, (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually, but the hardest was on picket from last Thursday morning ‘till Saturday morning – all the time four miles from camp, and both of the nights the rain poured in torrents, so much so that their clothes were completely saturated with the rain. They stood it nobly – not one complaining; but from the size of their haversacks on their return, it is no wonder that they were satisfied and are so eager to go again tomorrow. I heard one of them say ‘there was such nice cabbage, sweet and Irish potatoes, turnips, &c., out where their duty called them, and then there was a likelihood of a Rebel sheep or young porker advancing over our lines and then he could take them as ‘contraband’ and have them for his own use.’ When they were out they saw about a dozen of the Rebel cavalry and would have had a bout with them, had it not been for…unlucky circumstance – one of the men caught the hammer of his rifle in the strap of his knapsack and caused his gun to fire; the Rebels heard the report and scampered in quick time….

Unknown regiment, Camp Griffin, Virginia, fall 1861 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain; click to enlarge).

On Friday morning, 22 October 1861, the 47th engaged in a divisional review, described by historian Lewis Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” In late October, according to Schmidt, the men from Companies B, G and H woke at 3 a.m., assembled a day’s worth of rations, marched four miles from camp, and took over picket duties from the 49th New York:

Company B was stationed in the vicinity of a Mrs. Jackson’s house, with Capt. Kacy’s Company H on guard around the house. The men of Company B had erected a hut made of fence rails gathered around an oak tree, in front of which was the house and property, including a persimmon tree whose fruit supplied them with a snack. Behind the house was the woods were the Rebels had been fired on last Wednesday morning while they were chopping wood there.

In his letter of 17 November, Henry Wharton revealed still more details about life at Camp Griffin:

This morning our brigade was out for inspection; arms, accoutrements [sic], clothing, knapsacks, etc, all were out through a thorough examination, and if I must say it myself, our company stood best, A No. 1, for cleanliness. We have a new commander to our Brigade, Brigadier General Brannen [sic], of the U.S. Army, and if looks are any criterion, I think he is a strict disciplinarian and one who will be as able to get his men out of danger as he is willing to lead them to battle….

The boys have plenty of work to do, such as piquet [sic] duty, standing guard, wood-chopping, police duty and day drill; but then they have the most substantial food; our rations consist of fresh beef (three times a week) pickled pork, pickled beef, smoked pork, fresh bread, daily, which is baked by our own bakers, the Quartermaster having procured portable ovens for that purpose, potatoes, split peas, beans, occasionally molasses and plenty of good coffee, so you see Uncle Sam supplies us plentifully….

A few nights ago our Company was out on piquet [sic]; it was a terrible night, raining very hard the whole night, and what made it worse, the boys had to stand well to their work and dare not leave to look for shelter. Some of them consider they are well paid for their exposure, as they captured two ancient muskets belonging to Secessia. One of them is of English manufacture, and the other has the Virginia militia mark on it. They are both in a dilapidated condition, but the boys hold them in high estimation as they are trophies from the enemy, and besides they were taken from the house of Mrs. Stewart, sister to the rebel Jackson who assassinated the lamented Ellsworth at Alexandria. The honorable lady, Mrs. Stewart, is now a prisoner at Washington and her house is the headquarters of the command of the piquets [sic]….

Since the success of the secret expedition, we have all kinds of rumors in camp. One is that our Brigade will be sent to the relief of Gen. Sherman, in South Carolina. The boys all desire it and the news in the ‘Press’ is correct, that a large force is to be sent there, I think their wish will be gratified….

On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review that was overseen by Colonel Tilghman Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

As a reward — and in preparation for bigger things to come, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan obtained brand new Springfield rifles for every member of the 47th Pennsylvania.

But fate had other plans for Second Lieutenant Charles A. Henry. Ailing with asthma, he worked with regimental physicians to try to bring his illness under control. But by late December of 1861, he was deemed too ill to continue serving with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. As a result, he resigned his commission on New Year’s Eve.

Return to Civilian Life

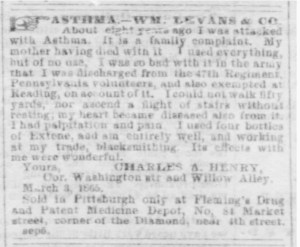

Advertisement which documented the asthma condition of Second Lieutenant Charles A. Henry, Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (The Pittsburgh Post, 8 September 1865, public domain; click to enlarge).

Following his resignation of his commission, Charles A. Henry returned home to Pennsylvania, where he continued to pursue a cure for his asthma — initially without success. Deemed as still too ill to serve, he was subsequently exempted from further military service.

By 1865, he had evidently found some measure of relief from his condition. According to an advertisement in the 8 September 1865 edition of The Pittsburgh Post, Charles A. Henry had first experienced symptoms of asthma sometime around 1857.

It is a family complaint. My mother having died with it. I used everything, but of no use. I was so bad with it in the army that I was discharged from the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania volunteers, and also exempted at Reading, on account of it. I could not walk fifty yards, nor ascend a flight of stairs without resting; my heart became diseased also from it. I had palpitation and pain. I used four bottles of Extene, and am entirely well, and working at my trade, blacksmithing. Its effects with me were wonderful.

Yours,

Charles A. Henry

Cor. Washington str and Willow Alley

March 3, 1865

Researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story have not yet located records that document what happened to Charles A. Henry after his name appeared in that advertisement, by have been able to determine that, in June of 1890, he was interviewed by an enumerator for the special veterans’ census. That federal census enumerator confirmed that Charles A. Henry was a resident of Siegfrieds Bridge in Allen Township in Northampton County at that time.

Death and Interment

What is also presently known is that Charles A. Henry died roughly two years later, at the age of sixty-four, in the city of Erie in Erie County, Pennsylvania, on 30 August 1892. Following funeral services, he was laid to rest at the Veterans Memorial Cemetery in Erie, which seems to indicate that he may have been a resident of the Pennsylvania Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home in Erie during the final months of his life.

Sources:

- “Asthma. — Wm. Levans & Co.” (advertisement in which former Second Lieutenant Charles A. Henry explains that asthma was the cause for his departure from the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry). Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The Pittsburgh Post, 8 September 1865.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Henry, Charles A., in Civil War Muster Rolls (Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Henry, Charles A., in Headstones Provided for Deceased Union Civil War Veterans (Pennsylvania Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home, Erie, Pennsylvania, 1892). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Henry, Charles A., in U.S. Census (“Special Schedule. — Surviving Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, and Widows, etc.”: Allen Township, Northampton County, Pennsylvania, 1890). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Roster of the 47th P. V. Inf.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 26 October 1930.

- Schmidt, Lewis G. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

You must be logged in to post a comment.