Alternate Surname Spellings: Kneller, Knoeller, Knöller, Neller

A first-generation German-American whose parents emigrated to the United States of America from the Kingdom of Württemberg during the early nineteenth century, John Kneller survived one of the darkest and most disastrous periods in American History to become one of the many Pennsylvanians who migrated west to the nation’s heartland in search of better lives.

A successful farmer in Iowa during the Reconstruction, Gilded Age and Progressive eras, he and his siblings, spouse, children, and other relatives worked hard to fuel, transport and transform a growing nation, through the crops they harvested, the wagons and railroad lines they built, and the oil drilling and delivery systems they installed and maintained in Indiana, Iowa, Montana, South Dakota, and Wyoming.

Their story is the story of America.

Formative Years

Born in Allentown, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania on 11 April 1842, John Kneller was a son of Gottlieb Friederich Kneller (1805-unknown) and Philippina Kneller (1823-unknown), who had emigrated from Germany sometime prior to 29 March 1835, according to records of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Schoenersville in Lehigh County, which documented that Friederich Kneller and his wife, “Philebino,” attended a Lord’s Supper event at their church on that date.

* Note: John Kneller’s father, Gottlieb Friederich Kneller, was born on 8 October 1805 in the town of Calmbach in the Kingdom of Württemberg (roughly three miles north of the Black Forest resort town of Bad Wildbad in the present-day German state of Baden-Württemberg). Known to family and friends as “Friederich” or “Frederick,” Gottlieb Friederich Kneller was a son of Johann Andreas Knöller (1756-1838) and Anna Maria (Rittmänn) Knöller (1759-1829). He was baptized at the Evangelische Kirche Calmbach during the fall of 1805.

John Kneller’s mother, Philippina, was born on 2 May 1823 in Höfen an der Enz in the Kingdom of Württemberg (in what is, today, the Karlsruhe region of Germany).

Very little else is presently known about John Kneller’s formative years. What is known for certain is that, by the winter of 1863, he was a twenty-one-year-old coachmaker living in Allentown, who was five feet, eight and one-half inches tall with dark hair, brown eyes and a light complexion.

American Civil War

Shortly before Christmas in 1863, John Kneller left all he knew behind and traveled from his home in Allentown, Pennsylvania to the city of Norristown in Montgomery County, where, on 19 December, he enrolled for military service with the Army of the United States. He then officially mustered in for duty that same day as a private with Company G of the battle-hardened 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Subsequently transported by ship to America’s Deep South, he connected with his regiment “in the field” in Louisiana on 26 April 1864 — the same day on which the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry reached its new duty station in Alexandria, Natchitoches Parish, according to regimental muster rolls.

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” in reference to the Union officer who designed it, Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 facilitated Union gunboat passage (public domain).

The timing of his arrival means that he was involved in the latter part pf the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ history-making Red River Campaign. It also means that his first duty assignment would have been to assist with the Union Army’s construction of “Bailey’s Dam,” a series of timber structures that were designed by Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey to be erected across a section of the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana in such a way that they would enable Union Navy gunboats to more easily navigate their way through the river’s notoriously difficult rapids and fluctuating water levels.

He and his new comrades were involved in that dam’s construction for roughly two weeks. According to Musician Henry D. Wharton of the 47th Pennsylvania’s C Company:

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gun boats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people will eat), so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the iron clads down the river. After a great deal of labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic, chute], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’ The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gunboat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

Private John Kneller and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were then ordered to march toward Avoyelles Parish. According to Wharton:

On Sunday, May 15th, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of the Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad where with the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. — We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed into line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired, and we advanced ’till dark, when the forces halted for the night with orders to rest on their arms. ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee.

“Sleeping on Their Arms” by Winslow Homer (Harper’s Weekly, 21 May 1864).

“Resting on their arms” (half-dozing, without pitching their tents, and with their rifles right beside them), they were now positioned just outside of Marksville, on the eve of the 16 May 1864 Battle of Mansura, which unfolded as follows, according to Wharton:

Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, they reached Missoula [sic, Mansura], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic, maneuvering] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic, were] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain directly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport [sic, Simmesport] on the Achafalaya [sic, Atchafalaya] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over.– The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of the army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic, there] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.

Continuing on, the healthy members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry marched for Simmesport and then Morganza, where they made camp again. While encamped there, nine formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the regiment in Beaufort, South Carolina (1862) and Natchitoches, Louisiana (1864) were officially mustered into the regiment between 22-24 June.

The regiment then moved on and arrived in New Orleans in late June. On the Fourth of July, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers received orders to return to the East Coast. Three days later, they began loading the regiment and its men onto ships, a process that unfolded in two stages. Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I boarded the U.S. Steamer McClellan on 7 July and departed that day, while the members of Companies B, G and K, including Private John Kneller, remained behind, awaiting transport. They subsequently departed aboard the Blackstone, weighing anchor and sailing forth at the end of that month. Arriving in Virginia, on 28 July, the second group reconnected with the first group at Monocacy, having missed an encounter with President Abraham Lincoln and the Battle of Cool Spring at Snicker’s Gap in mid-July (a battle in which the first group of 47th Pennsylvanians had participated).

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

General Crook’s Battle Near Berryville, Virginia, 3 September 1864 (James E. Taylor, public domain).

Attached to the Middle Military Division, U.S. Army of the Shenandoah, beginning in early August of 1864, and placed under the command of Union Major-General Philip H. Sheridan, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was assigned to defensive duties in and around Halltown, and also engaged over the next several weeks in a series of back-and-forth movements between Halltown, Berryville, Middletown, Charlestown, and Winchester as part of a “mimic war” being waged by Sheridan’s Union forces with those commanded by Confederate Lieutenant-General Jubal Early.

The 47th Pennsylvania then engaged with Confederate forces in the Battle of Berryville from 3-4 September.

Battles of Opequan and Fisher’s Hill

On 19 September 1864, Private John Kneller and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers next began a series of battles that would turn the tide of the American Civil War firmly in favor of the Union and help President Abraham Lincoln to secure re-election.

Together, with other regiments under the command of Union Major-General Philip Sheridan and Brigadier-General William Emory, commander of the 19th Corps (XIX Corps), the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers helped to inflict heavy casualties on Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate forces in the Battle of Opequan (also spelled as “Opequon” and known as “Third Winchester”).

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ march toward destiny began at 2 a.m. that 19 September as the regiment left camp and joined up with other regiments in the Union’s 19th Corps. Advancing from Berryville toward Winchester, the 19th Corps bogged down for several hours as Union wagon trains made their way slowly across the terrain. As a result, Early’s troops were able to dig in and wait.

The fighting, which began at noon, was long and brutal. The Union’s left flank (6th Corps) took a beating from Confederate artillery that was positioned on higher ground.

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union Army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces, Battle of Opequan, 19 September 1864 (Kurz & Allison, circa 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania and other 19th Corps regiments were directed by Brigadier-General William Emory to attack and pursue Major-General John B. Gordon’s Confederate forces. Some success was achieved, but casualties mounted as a Confederate artillery group opened fire on Union troops that were trying to cross clearing. When a nearly fatal gap began to open between the 6th and 19th Corps, Sheridan sent in units that were led by Brigadier-Generals Emory Upton and David A. Russell. Russell, hit twice (once in the chest), was mortally wounded.

The 47th Pennsylvania subsequently opened its lines long enough to enable the Union cavalry under William Woods Averell and the foot soldiers of Brigadier-General George Crook to charge the Confederates’ left flank. As the 19th Corps began pushing the Confederates back, with the 47th Pennsylvania in the thick of the fight, Early’s “grays” retreated.

Sheridan’s “blue jackets” ultimately went on to win the day.

Leaving twenty-five hundred wounded behind, the Rebels retreated to Fisher’s Hill, eight miles south of Winchester, where a second engagement, the Battle of Fisher’s Hill, was waged from 21-22 September. Following a successful morning flanking attack by Sheridan’s Union forces, which outnumbered Early’s Confederate troops three to one, Early’s troops fled to Waynesboro, but were pursued by the 47th Pennsylvania and other Union regiments. Afterward, the 47th Pennsylvanians made camp at Cedar Creek.

They would continue to distinguish themselves in battle, but they would do so without their two most senior leaders, Colonel Tilghman H. Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, who mustered out from 23-24 September, upon expiration of their respective terms of service. Fortunately, they were replaced by leaders who were equally respected for their front-line experience and temperament, including Major John Peter Shindel Gobin, formerly of Company C, who had been promoted up through the regimental officers’ corps to the regiment’s central command staff (and who would be promoted again on 4 November to the rank of lieutenant-colonel and appointed as the 47th Pennsylvania’s final commanding officer).

Battle of Cedar Creek

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, “Surprise at Cedar Creek,” captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle-pit positions, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

During the fall of 1864, Major-General Sheridan began the first of the Union’s true “scorched earth” campaigns, starving the enemy into submission by destroying Virginia’s farming infrastructure. Viewed today through the lens of history as inhumane, the strategy claimed the lives of many innocent civilians, whose lives were uprooted or even cut short by the inability to find food or adequate shelter. This same strategy, however, almost certainly contributed to the further turning of the war in the Union’s favor during the Battle of Cedar Creek on 19 October 1864.

Successful throughout most of their engagement with Union forces at Cedar Creek, Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederates began peeling off in ever greater numbers as the battle wore on in order to search for food to ease their gnawing hunger, thus enabling Sheridan’s well-fed troops to rally and win the day.

From a military standpoint, it was another impressive show of the Union’s might. From a human perspective, it was both inspiring and heartbreaking. During the morning of 19 October, Early launched a surprise attack on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. Early’s men were able to capture Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles, all while pushing seven Union divisions back. According to historian Samuel P. Bates:

When the Army of West Virginia, under Crook, was surprised and driven from its works, the Second Brigade, with the Forty-seventh on the right was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat…. Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers as he rode rapidly past them – ‘Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!'”

Sheridan Rallying His Troops, Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

In response, Union troops staged a decisive counterattack that punched Early’s forces into submission. Afterward, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas, who, in 1892, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked” that day.

But the day proved to be a particularly costly one for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. The regiment lost the equivalent of two full companies of men in killed, wounded and missing, as well as soldiers who were captured by Rebel troops and dragged off to prisoner of war (POW) camps, including the Confederates’ Libby Prison in Virginia, the notorious Salisbury Prison in North Carolina and the hellhole known as “Andersonville” in Georgia. Subjected to harsh treatment at the latter two, many of the 47th Pennsylvanians confined there never made it out alive. Those who did either died soon after their release, or lived lives that were greatly reduced in quality by their damaged health.

General J. D. Fessenden’s headquarters, U.S. Army of the Shenandoah at Camp Russell near Stephens City (now Newtown) in Virginia (Lieutenant S. S. Davis, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 31 December 1864, public domain).

Following those major battles, Private John Kneller and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered to march to Camp Russell near Winchester, where they rested and began the long recovery process from their physical and mental wounds. While still stationed at Camp Russell, Company G’s First Lieutenant George W. Hunsberger was honorably discharged from the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, on 30 November 1864, and was sent home to Pennsylvania.

In somewhat better shape after their most recent combat experience, Private Kneller and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians received new orders — to head for outpost and railroad guard duties at Camp Fairview in Charlestown, West Virginia — five days before Christmas.

1865 — 1866

Still stationed at Camp Fairview in West Virginia as the New Year of 1865 dawned, members of the regiment continued to patrol and guard key Union railroad lines in the vicinity of Charlestown, while other 47th Pennsylvanians chased down Confederate guerrillas who had made repeated attempts to disrupt railroad operations and kill soldiers from other Union regiments.

Assigned with his regiment to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah in February 1865, Private John Kneller was promoted to the rank of corporal on 1 February. He and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians then continued to perform their guerrilla-fighting duties until late March, when they were ordered to head back to Washington, D.C., by way of Winchester and Kernstown, Virginia.

Joyous News and Then Tragedy

Spectators gather for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, beside the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half-staff after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

As April 1865 opened, the battles between the Army of the United States and the Confederate States Army intensified, finally reaching the decisive moment when the Confederate troops of General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox on 9 April.

The long war, it seemed, was finally over. Less than a week later, however, the fragile peace was threatened when an assassin’s bullet ended the life of President Abraham Lincoln. Shot while attending an evening performance of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre on 14 April 1865, the president died from his head wound at 7:22 a.m. the next morning.

Shocked, and devastated by the news, which was received at their Fort Stevens encampment, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were given little time to mourn their beloved commander-in-chief before they were ordered to grab their weapons and move into the regiment’s assigned position, from which it helped to protect the nation’s capital and thwart any attempt by Confederate soldiers and their sympathizers to re-ignite the flames of civil war that had finally been stamped out.

So key was their assignment that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were not even allowed to march in the funeral procession of their slain leader. Instead, they took part in a memorial service with other members of their brigade that was officiated by the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental chaplain, the Reverend William D. C. Rodrock.

Unidentified Union infantry regiment, Camp Brightwood, Washington, D.C., circa 1865 (public domain).

Present-day researchers who read letters sent by 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers to family and friends back home in Pennsylvania during this period, or post-war interviews conducted by newspaper reporters with veterans of the regiment in later years, will learn that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were collectively heartbroken by Lincoln’s death and deeply angry at those whose actions had culminated in his murder. Researchers will also learn that at least one member of the regiment, C Company Drummer Samuel Hunter Pyers, was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train, while other members of the regiment were assigned to guard duty at the prison where the key assassination conspirators were being held during the early days of their imprisonment and trial, which began on 9 May 1865. The regiment was headquartered at Camp Brightwood during this period.

Attached to Dwight’s Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were permitted to march in the Union’s Grand Review of the National Armies, which took place in Washington, D.C. on 23 May.

Reconstruction

Ruins of Charleston, South Carolina as seen from the Circular Church, 1865 (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

On their final southern tour, Corporal John Kneller and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers served in Savannah, Georgia in early June. Assigned again to Dwight’s Division, this time they were attached to the 3rd Brigade, Department of the South. Relieving the 165th New York Volunteers in July, they quartered in the former mansion of the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury. Duties for the 47th during this phase were Provost (military police) and Reconstruction-related, including rebuilding railroads and other key segments of the region’s battered infrastructure.

Beginning on Christmas day of that year, Corporal Kneller and the majority of 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers, finally began to honorably muster out for the final time in Charleston, South Carolina — a process which continued through early January. Following a stormy voyage home, they disembarked in New York City. Weary, but eager to see their loved ones, they were transported to Philadelphia by train where, at Camp Cadwalader between 9-11 January 1866, they were officially given their honorable discharge papers.

According to regimental muster-out rolls, Corporal Kneller had last been given his regular soldier’s pay by the federal government on 30 September 1864, but had only been paid one hundred and forty dollars of the two hundred and twenty-two dollars in extra bounty funds that the government had promised to pay him for enlisting with a Union Army Unit. The federal government also owed him four dollars and thirty-six cents toward the purchase of his uniform. He did not receive the full amount that was due him when he was mustered out, however, because he still owed the sutler seven dollars and seventy-five cents for supplies that he purchased while in service to the nation.

Return to Civilian Life

47th Pennsylvania veteran John Kneller and his wife, Ellena (Huber) Kneller, circa 1880s (photo used with permission, courtesy of Kenneth Ballew).

Following his honorable discharge from the military, John Kneller returned home to Pennsylvania, where he married Berks County, Pennsylvania native Ellena Huber (1847-1935), who had been born on 16 November 1847 and was a daughter of native Pennsylvanians George M. Huber (1807-1881) and Lydia E. Hillegass (1809-1887).

Sometime in 1866, he and his new bride migrated west to Indiana. Traveling by train, they settled in Peru, Miami County, where they began to welcome the arrival of the first of their many children — Allen John Kneller (1867-1952), who was born in Peru on 31 October 1867 (alternate birth year: 1868), according to records of the U.S. Social Security Administration.

Arrival of the first passenger train in Waterloo, Blackhawk County, Iowa, 11 March 1861 (public domain).

Sometime prior to June of 1870, John Kneller packed up his family’s belongings and moved his wife, Ellena, and their son, Allen, to Iowa, where John was employed by J. P. Hummel as a wagon and coachmaker, and where their second son — George Frederick Kneller (1869-1951) — was born in Waterloo, Black Hawk County on 22 August 1869.

* Note: George Frederick Kneller would subsequently go on to marry Anna B. Dusenberry (1870-1949), a native of West Virginia who was a daughter of George Dusenberry (1826-1899) and Alcinda (Flowers) Dusenberry (1828-1903).

At some point after George Kneller’s birth, John and Ellena Kneller decided to make the long trip back to Pennsylvania to visit family and friends in Berks County, including Ellena’s brother, Henry Huber. It was there in Berks County, Pennsylvania that the Knellers’ twin daughters, Cora and Laura Kneller, were then born on 2 December 1871.

* Note: Researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story have not yet determined if the two youngest children of John and Ellena Kneller (Allen and George) traveled with them to Pennsylvania, or remained in Iowa. What is known for certain is that John and Ellena’s twins were born in Berks County. (Federal census records confirm that both girls were born in Pennsylvania.)

Cora Kneller would subsequently go on to marry William Edward King (1872-1943), a native of Adams County, Iowa who was a son of Jessie Barton King (1836-1906) and Isabelle Anna (Cline) King (1844-1910), while Laura Kneller would later wed William H. Griffin (1875-1944) and settle with him in the city of Des Moines, Polk County, Iowa.

John and Ellena Kneller then returned to the Midwest with their twin daughters. More children soon followed, including: Stella Belle Kneller (1874-1969), was born in Waterloo, Blackhawk County, Iowa on 21 August 1874 and later wed Arthur Alvin Henry (1873-1930) and settled with her husband in Clarenda, Iowa (by 1952); and Maud Kneller (1877-1961), who was born in that same county in January 1877 and later wed Frank Fiscus (1875-1964).

Sometime after daughter Maud’s birth in 1877, John Kneller decided to pack up his family and relocate them yet again. This time, he moved them to Carl Township in Adams County, Iowa, where he opened his own wagon and coachmaking business.

* Note: According to a brief summary of the Knellers’ family history that was published in a 1930 edition of The Des Moines Register, Ellena (Huber) Kneller stated that she and her family had “moved by prairie schooner and oxcart to the little community of Carl, twelve miles north of Corning.”

Sadly, tragedy struck the Kneller family on 10 December 1877 when patriarch John Kneller’s uninsured wagon shop was destroyed by fire. As a result, he and his family returned to the town of Waterloo, where his next child — Bert Boyer Kneller (1879-1949) — was born on 6 April 1879. (Bert would later go on to marry Emma Ludwig.)

The Knellers did not remain in Waterloo for long, however; by the time that the 1880 federal census was underway in Iowa in mid-June of that year, John Kneller and his family were back in Carl Township, Adams County, where John had found work as a carpenter. While there, he and his wife welcomed the arrivals of: Charles Henry Kneller (1882-1950), who was born on 31 March 1882 and later wed Clara Francis McCormick; and Frank Arthur Kneller (1885-1974), who was born on 14 September 1885 (alternate birth date: 15 September 1885) and later wed Ruby Elizabeth Ellenwood (1890-1954) and settled with her in Prescott, Iowa (by 1952).

* Note: Although one source for John Kneller’s history indicates that he and his wife had been the parents of ten children, one of whom died in infancy, federal census enunerators for both the 1900 and 1910 federal census reported that the Knellers had been the parents of nine children (all of whom were still alive in 1910). Additionally, none of the prior federal census records recorded the presence of an infant who would have been “the tenth child.”

After residing with his family in Carl for twenty-two years, John Kneller and his wife moved to a farm, in 1890, that was located roughly two and one-half miles west of Carl, and spent their remaining years together there at their farmhouse. On 26 November 1891, their son, Allen John Kneller, married Rosella May Snyder in Page County, Iowa. A daughter of Sylvester Snyder and Elizabeth (Homan) Snyder (1868-1914), she was known to family and friends as “Nellie.”

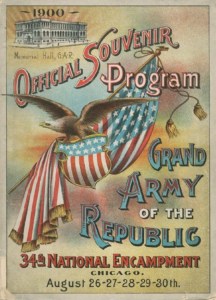

Front cover, souvenir program, Grand Army of the Republic’s annual national encampment, Chicago, Illinois, August 1900 (public domain).

By 1900, John Kneller’s household included his wife, their daughter, Maud, and their sons Charles, who was working the family’s farmland with him, and Frank, who was still attending school. In addition to an apple orchard, his farmland produced crops of corn, oats and wheat. A member of the Republican Party who was politically active throughout his post-war life, according to multiple newspaper reports of the nineteenth century, John Kneller was also a member of the Grand Army of the Republic. In August 1900, he traveled to Chicago, Illinois to attend the national encampment of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.). That year, G.A.R. members debated whether or not to lobby the United States Congress to radically alter U.S. Civil War Pension legislation so that veterans’ pension awards would be based on their length of service rather than the type and degree of their disabilities. (They ultimately chose not to ask for that change.)

Less than two years later, his “blacksmith shop was blown to pieces” during a Friday night explosion in April 1902, according to the Adams County Free Press. But he bounced back and was able to attend the Adams County veterans’ association’s annual reunion from 11-13 September at the fairgrounds in Corning, Iowa.

During the summer of 1908, the Knellers played host to Ellena’s brother, Henry Huber, and his wife and son, who had traveled from their home in the town of Chapel in Berks County, Pennsylvania for an extended visit. According to the Adams County Free Press, Ellena hadn’t seen her brother for fifteen years. Ellena’s nephew, Charles Huber, subsequently traveled on to Denver, Colorado.

By 1910, John Kneller’s son, Charles Henry Kneller, had moved away from home in order to begin his own family line, leaving brother Frank to serve as their father’s farmhand. Later that same year, John Kneller’s son, Frank, wed Ruby Ellenwood, a resident of North Platte, Nebraska, at the home of her parents, Mr.and Mrs. E. E. Ellenwood, on 20 December. According to the Adams County Free Press, “The contracting parties were born and reared in this county [Adams] and will make their home in the vicinity of Carl.”

Less than a year later, at 3 p.m. on 6 September 1911, the marriage of Frank Fiscus and John Kneller’s daughter, Maud, “was quietly celebrated at the residence of Rev. A. Y. Cupp” in Carl Township. The young couple then migrated north to Canada, where Frank Fiscus already had “a home in readiness for his bride,” according to the Adams County Free Press.

A week after their daughter’s marriage, John Kneller and his wife, Ellena, traveled back to Berks County, Pennsylvania for a two-month visit with relatives, and arrived back at their home in Iowa on 15 November. According to the Adams County Free Press, “It had been nearly 20 years since Mr. and Mrs. Kneller visited in Pennsylvania and they had a real good visit. They stopped in Des Moines to see their daughter, Mrs. W. H. Griffin, before coming home.”

By late August or early September 1912, newlyweds Maud (Kneller) Fiscus and Frank Fiscus were settling in as guests of John and Ellena Kneller, having returned from Canada, according to the Adams County Free Press.

Illness, Death and Interment

Ailing during his final years, John Kneller lived out his remaining years at his farm west of Carl in Adams County, where he passed away two days before Christmas in 1914. Seventy-two years old at the time of his death, he was laid to rest at the Forest Hill Cemetery in Mount Etna, Adams County on 27 December.

He was survived by his wife and these children: Allen John Kneller of Tripp, South Dakota; George Frederick Kneller, Bert Boyer Kneller, Charles Henry Kneller, Frank Arthur Kneller, and Cora (Kneller) King, all of whom still resided in Carl; Laura (Kneller) Griffin, of Des Moines; and Stella Belle (Kneller) Henry and Maud (Kneller) Fiscus, both of whom resided in Corning.

What Happened to John Kneller’s Widow?

Ellena (Huber) Keller, aged eighty-three, standing beside the airplane that took her on her first flight on 6 July 1930 (The Des Moines Register, 8 July 1930, public domain).

John Kneller’s widow survived him by more than two decades and continued to reside at the Kneller family farmhouse in Carl for the remainder of her days — with the exception of periodic visits to family and friends in Corning, Des Moines and other communities in Iowa. In 1915, she was awarded a U.S. Civil War Widow’s Pension of twelve dollars per month (the equivalent, annually, of roughly four thousand six hundred U.S. dollars in 2025).

On Sunday, 6 July 1930, eighty-three-year-old Ellena (Huber) Kneller became “one of the oldest flyers in Iowa … when she took her first airplane ride,” according to The Des Moines Register.

“Scared?” she said as the plane landed at the municipal airport after a twenty minute flight over Des Moines at a 2,000 foot altitude, “I should say not!”

“I’ve ridden in and on everything but a submarine and I don’t see why people should be any more afraid in a plane than riding behind a pair of frisky colts.”

Refuses to Be Dissuaded.

When Mrs. Kneller was assisted into the cabin plane at the municipal airport Sunday afternoon, several persons attempted to dissuade her. They thought, because of her age, Mrs. Kneller might not survive the flight.

But her enthusiasm for flying grew the longer the plane soared over the city.

“Say,” she yelled at Pilot F. C. Anderson, beside whom she sat, “I’d love to have you fly me home when I go. You could land in our pasture and we would sure surprise all the folks back there.”

Traveled by Oxcart.

Mrs. Kneller was impressed particularly with the air views of the state fair grounds, the state capitol grounds and the lazy windings of the Des Moines river through the city.

Born in Philadelphia in 1847, she came to Waterloo by rail in 1866 and nine years later moved by prairie schooner and oxcart to the little community of Carl, twelve miles north of Corning.

Here for Reunion.

She came to Des Moines recently for a family reunion at the home of her daughter, Mrs. W. H. Griffin, South East Fourteenth street and Higgins avenue.

Sunday was the first time in her four score and three years of life that Mrs. Kneller was ever near an airplane.

“Sure,” she is telling friends. “Sure. I’m going to fly again.”

After a long, full life, Ellena Kneller died at her home in Carl at the age of eighty-seven, on 12 April 1935. Following funeral services at the First Baptist Church in Adams County, she was laid to rest beside her husband at the First Baptist Church Cemetery (now the Forest Hill Cemetery in Mount Etna, Adams County). According to her obituary in the Adams County Free Press:

Adams county lost another pioneer character this week when Mrs. Ellena Kneller of Carl township passed away, after having lived 45 years of her life on the same farm in that community….

Mrs. Kneller lived a quiet home life and was an invalid about four years prior to her death. She enjoyed the radio programs and would often join in singing some of the religious hymns. Her many friends of Carl community unite in expressing their sympathy to all the bereaved relatives….

What Happened to John Kneller’s Children?

Unidentified residents of Tripp County, South Dakota, circa late 1890s-early 1900s (public domain; click to enlarge).

A farmer in Carl Township, Iowa during the early 1890s, John Kneller’s son, Allen John Kneller, who had married Rosella May Snyder in Page County, Iowa on 26 November 1891, was divorced from her before 1904. Known to family and friends as “Al,” he subsequently migrated northwest to South Dakota, and settled near the town of Tripp in Hutchinson County, where, on 16 October 1904, he wed Maggie F. Maxon (1878-1957), who was a native of Dana, LaSalle County, Illinois and a daughter of Albert Maxon (1854-1932) and Della (Morninger) Maxon (1861-1933). Four years later Al and Maggie Kneller welcomed the arrival of a son, John Albert Kneller (1908-1974), who was born on 6 August 1908 in Wessington, Jerauld County, South Dakota (now on the border between Beadle and Hand counties). By 1910, the trio resided in Cedar Township, Stanley County, South Dakota, where Al Kneller was supporting his new family as a farmer. Al and Maggie Kneller’s second son, Lloyd Milton Kneller (1914-1986), was subsequently born in Tripp, Hutchinson County, South Dakota on 26 May 1914. (Lloyd would go on to serve in the U.S. Army during World War II and became the husband of Mabel McRae in Rawlins, Wyoming on 24 February 1984.)

Following Lloyd’s birth, Al Kneller returned to Iowa in early October 1914 to visit with his parents in Carl Township, Adams County. He then returned home to South Dakota to prepare for the spring 1915 relocation of his family to Montana, where he had rented a ranch. He then established a more permanent home with them in Columbus, Stillwater County, Montana, where he was employed as a railroad laborer — a position he still held on 9 January 1920 when his home was visited by a federal census enumerator.

Later that same year (1920), he and his family moved again — this time to the city of Casper in Natrona County, Wyoming, where he was involved in oil pipeline construction. Retired by 1940, Al Kneller and his wife and their two sons were still living in the same house in Natrona County where they had lived since at least 1930. Both sons were employed as drillers in the oil industry. Ailing with heart disease during his later years, Al Kneller was also diagnosed by physicians as increasingly senile. After a long, full life, he fell ill with lobar pneumonia in late July 1952 and died at the age of eighty-four, at the Memorial Hospital of Natrona County in Casper, on 26 July 1952, and was laid to rest at Casper’s Highland Cemetery.

Following his marriage to Anna B. Dusenberry on 31 July 1897, John Kneller’s son, George Frederick Kneller welcomed the births with her of: Ola E. Kneller (1899-1971), who was born in Carl Township on 22 August 1899 and later wed Otto F. Anderson (1896-1961); and George Frederick Kneller, Jr. (1910-1910), who was born in Carl, Adams County, Iowa on 17 December 1910, but died eight days later in Carl, on Christmas Day. By 1900, George F. Kneller, Sr. was residing with his wife and daughter, Ola, in Carl Township, where he was working hard as a farmer to support his young family, which he continued to do through 1910, when federal census records documented that he and his wife and daughter lived on farmland that adjoined the farm of George’s father, John Kneller. By 1920, however, George F. Kneller was employed as the city marshal in the City of Carl in Adams County. Living with him were his wife and daughter, Ola. By early 1925, George Kneller and his wife, Anna, were “empty nesters” living in Corning, Adams County. Residing with them was fifty-four-year-old roomer Abbie Davis. By 1930, George Kneller had returned to his old farm life in Carl Township, where he and his wife, Anna, were the sole inhabitants of their home. Still farming his land in 1940, George Frederick Kneller, Sr. was widowed by his wife, Anna, when she passed away in Adams County in 1949. He then moved to the City of Corning in Adams County, where he resided alone in April 1950. In his early eighties when he passed away at his home in Corning on 6 June 1951, he was laid to rest beside his wife at the Carl Cemetery in Carl Township, Adams County.

Following her marriage to William Edward King in 1884, John Kneller’s daughter, Cora (Kneller) King welcomed the Iowa births of: Gladys Lloyd King (1894-1930), who was born in Adams County on 26 October 1894 and later settled in Tarrant County, Texas; Emma Faye King (1896-1974), who was born in Adair County, Iowa on 21 June 1896 and later wed Lloyd Ellsworth Goodvyn (1896-1978), before divorcing him and marrying Clifford Virgil Haley (1905-1981); and Fred Allen King (1899-1918), who was born in Carl, Adams County on 17 April 1899, but died from the flu in Ames, Story County on 16 October 1918 (during the Spanish Influenza epidemic). Cora (Kneller) King then also suffered an untimely death, passing away at the age of fifty-six in Creston, Union County, Iowa on 23 March 1928. Following funeral services, she was laid to rest at the at the Forest Hill Cemetery in Mount Etna, Adams County.

Following her marriage to William H. Griffin on 26 February 1896, John Kneller’s daughter, Laura (Kneller) Griffin, initially settled with her husband in the city Bridgewater in Adair County, Iowa, before making a life with him in Des Moines, Polk County, Iowa, where William Griffin was hired as a street car operator by the Des Moines Railway Company. Together, they welcomed the births of: Earl Otis Griffin (1896-1979), who was born in Bridgewater, Adair County on 20 October 1896 and later wed Dorothy E. Fuller (1899-1991); Verne Everett Griffin (1898-1980), who was born in the Corning, Adams County, Iowa on 27 August 1898 and later wed Dorothy E. Fuller (1899-1991) and settled in New Mexico; Frank Charles Griffin (1900-1982), who was born in Corning on 29 January 1900 and later wed Iva Lorene Funk (1907-2001); Irma Griffin (1901-1959), who was born in 1901 and later wed Donald O. Sullivan (1902-1981); Alma Ruth Griffin (1903-1988), who was born in Bates County, Missouri on 29 September 1903 and later adopted the married surname of Vorrath before divorcing her husband; and Edna Griffin (1905-1997), who was born in Corning, Iowa on 15 June 1905 and later wed Paul Francis Boehler (1900-1974). Widowed by her husband when he died from a heart attack at the age of sixty-nine in Des Moines on 27 November 1944, Laura (Kneller) Griffin subsequently relocated to Fort Lauderdale, Florida in 1952. Her daughters, Alma and Edna, also resided there. During the late winter of 1966 or early 1967, Laura (Kneller) Griffin fractured her hip during a severe fall. She died eight months later, at the Broward Convalescent Home, from complications related to her injury. In her mid-nineties when she passed away in Fort Lauderdale on 19 August 1967, her remains were subsequently transported back to Iowa for interment beside her husband at the Avon Cemetery in Des Moines.

Following her marriage to Arthur Alvin Henry in Corning, Adams County on 30 December 1897, John Kneller’s daughter, Stella Belle (Kneller) Henry, initially settled with him Carl, where her husband farmed the land. Together, they welcomed the births of: Glen Arthur Henry (1900-1950), who was born in Carl on 8 July 1900 and later wed Elsie Vera Hubatka (1906-1986); and Lois Margaret Henry (1903-2002), who was born in Carl on 18 September 1903 and later wed Earle Lowell Pottinger (1901-1990). By 1914, Stella (Kneller) Henry was residing with her husband and children in the city of Corning; by 1920, however, she and her family were residing in Prescott Township, Adams County, where her husband was still working as a farmer. “Empty nesters” by mid-1930, she and her husband had relocated to the city of Creston in Union County, Iowa, where her husband had found work as the manager of a second-hand store — a hard-to-come-by job during the Great Depression. Also living with them that year was Clifford Wilson, a twenty-seven-year-old lodger who worked as a railroad laborer. Widowed by her husband on Christmas Day that same year (1930), Stella (Kneller) Henry subsequently relocated to Clarenda, Iowa, where, in 1940, she was employed as a live-in housekeeper by gas station owner Darrell Davison. By 1950, she was living at the Clarenda home of her daughter and son-in-law, Lois and Earl Pottinger. After a long, full life, Stella (Kneller) Henry died in her mid-nineties in 1969, and was laid to rest beside her husband at the Forest Hill Cemetery in Mount Etna, Adams County.

Following her marriage to Frank Fiscus and return from a reported relocation to Canada with her husband, John Kneller’s daughter, Maud (Kneller) Fiscus, settled in at the home of her parents in Carl Township, Adams County, Iowa. By 1920, she and her husband were living alone in Carl Township, where her husband was engaged in farming. Sometime before April 1930, however, the still-childless couple migrated north to Wisconsin, where they settled in Wyalusing Township in Grant County and where Maud’s husband, Frank, also began to farm land from then on — and into the 1940s. Retired from the farming life by the time of the 1950 federal census, the couple had moved to Bagley in Grant County, Wisconsin, where Maud (Kneller) Fiscus continued to reside with her husband for more than a decade. In her early eighties when she passed away at a nursing home in Prairie di Chien, Crawford County, Wisconsin, on 2 May 1961, she was subsequently laid to rest at the Bagley Cemetery in Bagley, Grant County.

Following his marriage to Clara Frances McCormick, a twenty-three-year-old native of Carl Township, Iowa, in Prescott, Iowa on 23 March 1904, John Kneller’s son, Charles Henry Kneller, also grew up to become a farmer in Carl Township. He and his wife then welcomed the births of daughters Eva Laurene Kneller (1905-1985), who was born in Prescott on 25 March 1905 and later wed James Olin Perry (1895-1978); and Wilma Joy Kneller (1909-1982), who was born in Carl Township on 16 October 1909, wed Chauncey William Crowson (1897-1967) and later settled with him in the city of Omaha in Douglas County, Nebraska. By 1930, Charles H. Kneller and his wife had relocated to the city of Creston in Union County, Iowa, where he again took up farming. Still residing with his wife in Creston in 1940, he was documented by that year’s federal census as the proprietor of a dairy. Mostly retired by April 1950, he continued to bring in money by performing odd jobs as needed, until he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage on 25 July 1950. Admitted to the Greater Community Hospital in Creston, he died there at the age of sixty-eight on 14 August. Following funeral services, he was laid to rest at that city’s Graceland Cemetery.

Following his marriage to Emma Ludwig, John Kneller’s son, Bert Boyer Kneller, settled with her in Carl Township, where he became a farmer. Together, they welcomed the births of: Bethel Mae Kneller (1913-1974), who was born in Corning in 1913, became a licensed practical nurse, married Thomas Meeks and settled with him in the city of Omaha in Douglas County, Nebraska, before divorcing him and marrying Frances Carns, and later relocating to Tacoma, Washington; Ruth Esther Kneller (1914-2000), who was born in Corning and later wed Casper Carlyle Van Eaton (1905-1992); Leneve Doris Kneller (1916-2003), who was born on 10 July 1916 and later wed Lee Edward Richey (1908-1950); Berdie Ellena Kneller (1922-1988), who was born on 17 July 1922 and later wed Thomas Meeks; Max Junior Kneller (1925-1995), who was born on 6 March 1925; and Rokel Dean Kneller (1929-1992), who was born on 19 November 1929 and later wed Lois J. Barbarich. Still farming the land in Carl Township during the 1920s and 1930s, Bert Kneller’s household in 1920 included his wife and their daughters, Bethel, Ruth and Leneve, and Bert’s mother, Ellena (Huber) Kneller, while his household in 1930 now also included his children, Berdie, Max and Rokel. By 1940, though, Bert Kneller had relocated his wife to Washington Township in Adams County, where he had found work at a quarry. Residing with him that year were his wife and their children: Berdie, Max, and Dean, as well as Bert’s granddaughter, Charlotte Kneller, and Bert’s daughter, Bethel (Kneller) Meeks and Bethel’s husband, Thomas Meeks, and their children, Raymond and Marjorie Meeks. Less than a decade later, Bert Kneller was gone. After suffering a cerebral hemorrhage on 19 January 1949, he died on 26 January in rural Washington Township, Adams County, just three months shy of his seventieth birthday. His remains were subsequently returned to Adams County for burial in the same cemetery where his parents were interred (the Forest Hill Cemetery in Mount Etna, Adams County).

Following his marriage to Ruby Elizabeth Ellenwood in North Platte, Nebraska on 10 December 1910, John Kneller’s son, Frank Arthur Kneller, settled with her on a farm that was located south of the city of Corning in Adams County. Together, he and his wife welcomed the births: of Helen Lucille Kneller (1911-1974), who was born in 1911 and later wed Edward Louis Briles (1894-1978); Hollis Harold Kneller (1913-2006), who was born in Corning on 28 March 1913 and later wed Mary Veone Cooper (1916-1986); and Doral Velma Kneller (1915-1943), who was born near Carl in Carl Township, Adams County on 19 October 1915.

Prescott High School, Prescott, Adams County, Iowa, circa early 1900s (public domain; click to enlarge).

Sometime before April 1930, Frank Kneller packed up his growing family and moved them to a farm in Prescott, Adams County, where more children soon followed: Lavon Doris Kneller (1917-2006), who was born in Prescott on 1 August 1917 and later wed Elmer A. Rathje (1920-2012) and settled with him in York County, Nebraska; Dale Lyle Kneller (1920-1995), who was born in Prescott on 25 July 1920 and later became the husband of Muriel Christ (1919-2012) and worked as a supervisor for the Iowa Department of Revenue; and Ronald Burdette Kneller (1922-1944), who was reported as missing in action while serving as a staff sergeant with the 515th Squadron of the 376th Bomb Group during World War II.

By 1935, Frank Kneller was serving as president of the school board in Prescott, Iowa. Still farming the land in Prescott and still residing there with his wife, Frank Kneller’s household included: Hollis, who was employed as a bus driver; Doral and Ronald, neither of whom were working; and Dale, who was helping his father with the farm.

Sadly, this became a difficult period for Frank Kneller and his family, as the health of his daughter, Doral, declined. Doral, who had fallen ill with scarlet fever when she was just four years old, had become so fragile by the time that she had reached her mid-twenties that her parents were motivated to seek treatment for her at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota in 1943. Unfortunately, the physicians at Mayo were unable to help her, and she died shortly after returning home. Just twenty-seven years old at the time of her death from heart disease, she was eulogized by the Adams County Free Press as “a modest, unassuming girl, always courteous and kind. All little children loved her.”

By 1950, Frank Kneller and his wife were “empty nesters” in Prescott. Sometime in 1970, he moved into the Valley View retirement home in Des Moines, Iowa, where he passed away at the age of eighty-eight, on 5 February 1974. Following funeral services, he was laid to rest at the Evergreen Cemetery in Prescott, Adams County, Iowa.

Sources:

- “A. J. Kneller Dies Here Saturday” (obituary of John Kneller’s son, Allen John Kneller). Casper, Wyoming: Star-Tribune, 27 July 1952.

- Allen John Kneller (the oldest son of John Kneller), in U.S. Social Security Applications and Claims Index. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Social Security Administration.

- Allen John Kneller (the oldest son of John Kneller), in Death Certficates (state file no.: 1395, date of death: 26 July 1952). Cheyenne, Wyoming: State of Wyoming, Department of Public Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteerss, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- “Bert B. Kneller” (a son of John Kneller), in “Obituaries.” Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 3 February 1949.

- Bert D. Kneller [sic, middle name: “Boyer”] (a son of John Kneller), in Death Certificates (birth no.: 00017, date of death: 26 January 1949). Des Moines, Iowa: Iowa State Department of Health, Division of Vital Statistics.

- Charles Henry Kneller, in Death Certificates (birth no.: 17695, date of death: 14 August 1950). Des Moines, Iowa: Iowa State Department of Health, Division of Vital Statistics.

- Ellena Kneller (announcement of the U.S. Civil War Widow’s Pension award to John Kneller’s widow), in “Hawkeye State News.” Tingley, Iowa: Tingley Vindicator, 2 September 1915.

- Fiscus, Frank and Maud (a daughter of John Kneller), in U.S. Census (Carl Township, Adams County, Iowa, 1920). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Fiscus, Frank and Maud (a daughter of John Kneller), in U.S. Census (Wyalusing Township, Grant County, Wisconsin, 1930, 1940). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Fiscus, Frank and Maud (a daughter of John Kneller), in U.S. Census (Bagley, Grant County, Wisconsin, 1950). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Frank Kneller (a son of John Kneller), in “Prescott News Briefly Told.” Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 23 May 1935.

- “Frank Arthur Kneller” (obituary of a son of John Kneller). Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 14 February 1974.

- Friederich and Philebino Kneller, in Church Records (Lord’s Supper, Evangelical Lutheran Church, Schoenersville, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, 29 March 1835). Schoenersville, Pennsylvania: Christ Evangelical Lutheran Church.

- “G.A.R. Breaks Camp: Grand Army Men Finish All Their Business and Elect Officers.” Chicago, Illinois: The Daily Inter Ocean, 31 August 1900.

- Geo. F. Kneller (groom) and John (father) and Elena Huber (mother); and Dusenberry, Anna (bride) and George (father) and Alcinda Flowers (mother), in Iowa Marriage Records (Adams County, Iowa, 31 July 1897). Des Moines, Iowa: Iowa State Archives.

- “George F. Kneller” (obituary of a son of John Kneller). Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 14 June 1951.

- George F. Kneller (a son of John Kneller), in Death Certificates (birth no.: 10969, date of death: 6 June 1951). Des Moines, Iowa: Iowa State Department of Health, Division of Vital Statistics.

- George Frederick Kneller (obituary of a grandson of John Kneller and a son of George Frederick Kneller, Sr.). Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 4 January 1911.

- Gottlieb Friederich Knöller (the father of American Civil War soldier John Kneller) and Andreas and Anna Maria Knöller (Gottlieb’s parents), in Birth and Baptismal Records (Evangelische Kirche Calmbach, Calmbach, Kingdom of Württemberg, 8 October 1805). Bad Wildbad, Germany: Evangelische Kirchengemeinde Calmbach.

- Griffin, William H., Laura (a daughter of John Kneller), Earl O., Vern E., and Charles F. Griffin, in U.S. Census (Quincy Township, Adams County, Ohio, 1900). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Griffin, William, Laura (a daughter of John Kneller), Earl, Vern, Frank, Erma, Alma, and Edna, in U.S. Census (Des Moines, Polk County, Ohio, 1910). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Grodzins, Dean and David Moss. “The U.S. Secession Crisis as a Breakdown of Democracy,” in When Democracy Breaks: Studies in Democratic Erosion and Collapse, from Ancient Athens to the Present Day (chapter 3). New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2024.

- Henry, Arthur A. and Stella B. (a daughter of John Kneller), in U.S. Census (Carl Township, Adams County, Iowa, 1900). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Henry, Arthur A., Stella B. (a daughter of John Kneller), Glen A., and Lois M., in U.S. Census (Carl Township, Adams County, Iowa, 1910). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Henry, Arthur A., Stella B. (a daughter of John Kneller), Glen A., and Lois M., in U.S. Census (Prescott Township, Adams County, Iowa, 1920). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Henry, Arthur and Stella (a daughter of John Kneller); and Wilson, Clifford (a lodger), in U.S. Census (Creston City, Union County, Iowa, 1930). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Henry, Stella (a daughter of John Kneller who was employed as a housekeeper at the home of Darrell Davison); and Davison, Darrell (head of household), in U.S. Census (Clarinda, Page County, Iowa, 1940). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Iowa Department of the Grand Army of the Republic.” Iowa: Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War, Department of Iowa, retrieved online 20 August 2025.

- John Kneller (blacksmith shop explosion), in “Carl Township.” Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 30 April 1902.

- John Kneller (brief report on the destruction by fire of his wagon making shop in Adams County, Iowa), in “Town and County Matters.” Waterloo, Iowa: The Daily Courier, 19 December 1877.

- John Kneller (death announcement), in “Carl and Vicinity.” Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 30 December 1914.

- John Kneller, in Death and Burial Records (Carl, Adams County, Iowa, 23 and 27 December 1914). Des Moines, Iowa: Iowa State Archives.

- John Keller, in “Decoration Day at Mt. Etna.” Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 11 June 1913.

- “John Kneller,” in “Died.” Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 30 December 1914.

- “John Kneller,” in “Our Local Observatory.” Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 3 May 1900.

- John Kneller, in “The Carl Budget.” Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 30 August 1900.

- John Kneller and Al Kneller (mentions the relocation of John Kneller’s son, Allen Kneller, to South Dakota and Montana), in “Southwest Carl.” Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 10 October 1914.

- John Kneller and Clara Frances McCormick, in Iowa Marriage Records (Prescott, Iowa, 23 March 1904). Des Moines, Iowa: Iowa State Archives.

- Kneller, Allen J. (groom) and John (father); and Rosella Snyder (bride), in Iowa Marriage Records (Page County, Iowa, 26 November 1891). Des Moines, Iowa: Iowa State Archives.

- Kneller, Albert J. [sic,”Allen John Kneller”] (the oldest son of John Kneller), Maggie F. and John A. (a grandson of John Kneller and a son of Allen John Kneller), in U.S. Census (Cedar Township, Stanley County, Iowa, 1910). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, Allen John (the oldest son of John Kneller), Maggie F., and John A. and Lloyd M. (grandsons of John Kneller and sons of Allen John Kneller), in U.S. Census (Columbus Town, Stillwater County, Montana, 1920). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, Allen John (the oldest son of John Kneller), Maggie F., and John A. and Lloyd M. (grandsons of John Kneller and sons of Allen John Kneller), in U.S. Census (Natrona County, Wyoming, 1940). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Kneller-Ellenwood” (marriage of John Kneller’s son, Frank, to Ruby Elizabeth Ellenwood). Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 31 December 1910.

- Kneller, Bert (a son of John Kneller), Ella, Bethel, Ruth, Leonore [sic, “Leneve”], and Elena [sic, “Ellena”] (John Kneller’s widow and Bert Kneller’s mother), in U.S. Census (Carl Township, Adams County, Iowa, 1920). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, Bert B. (a son of John Kneller), Emma, Bethel M., Ruth E., Leneve D., Birdie O. [sic, “Berdie Ellena”], Max J., Rohell D. [sic, “Rokel Dean”], and Ellena (John Kneller’s widow and Bert Kneller’s mother), in U.S. Census (Carl Township, Adams County, Iowa, 1930). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, Bert (a son of John Kneller), Emma, Birdie [sic, “Berdie Ellena”], Max, Dean [sic, “Rokel Dean”], and Charlotte (a granddaughter of Bert Kneller); and Meeks, Thomas, Bethel (a daughter of Bert Kneller), Raymond, and Marjorie, in U.S. Census (Washington Township, Adams County, Iowa, 1940). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, Charles H. (a son of John Kneller), Clara F., Eva Laurene, and Wilma J., in U.S. Census (Carl Township, Adams County, Iowa, 1910). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, Charles H. (a son of John Kneller) and Clara F./Mary, in U.S. Census (Creston City, Union County, Iowa, 1930, 1940, 1950). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, Frank (a son of John Kneller), Ruby, Helen, Hollis, Doral, and Lavon, in U.S. Census (Carl Township, Adams County, Iowa, 1920). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, Frank A. (a son of John Kneller, Ruby E., Helen, Hollis, Doral, Lavon, Dale, and Ronald, in U.S.Census (Prescott, Adams County, Iowa, 1930). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, Frank (a son of John Kneller, Ruby, Hollis, Doral, Dale, and Ronald, in U.S.Census (Prescott, Adams County, Iowa, 1940). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, Frank (a son of John Kneller and Ruby, in U.S. Census (Prescott, Adams County, Iowa, 1950). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, George (the oldest child of John Kneller) and Anna; and Davis, Abbie (a boarder), in Iowa State Census (Corning, Adams County, Iowa, 1925). Des Moines, Iowa: Iowa State Archives.

- Kneller, George F. (the second oldest child of John Kneller), Anna B. and Olla, in U.S. Census (Carl Township, Adams County, Iowa, 1900, 1910). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, George F. (the second oldest child of John Kneller), Anna B. and Olla, in U.S. Census (City of Carl, Adams County, Iowa, 1920). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, George F. (the second oldest child of John Kneller) and Anna B., in U.S. Census (Carl Township, Adams County, Iowa, 1930, 1940). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, John, in Civil War Muster Rolls (Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Kneller, John, in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 (Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Kneller, John, in Grand Army of the Republic Membership Records (Department of Iowa). Des Moines, Iowa: Iowa State Archives.

- Kneller, John, Ellen, Allen, and George, in U.S. Census (Waterloo, Black Hawk County, Iowa, 1870). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, John, Helena, Allen J., George F., Cora, Laura, Stella, Maud, and Baby [sic, “Bert Boyer Kneller”], in U.S. Census (Waterloo, Black Hawk County, Iowa, 1880). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, John, Ellen, Allen, George, Laura, Cora, Stella, Maud, Birdie B. [sic, “Bert B.”], and Charles, in Iowa State Census (Carl, Adams County, Iowa, 1885). Des Moines: Iowa State Archives.

- Kneller, John and Ellena, in U.S. Civil War Pension General Index Cards (veteran’s application no.: 897286, certificate no.: 694752, filed by the veteran from Iowa, 21 August 1890; widow’s application no.: 1040683, certificate no.: 794958, filed by the widow from Iowa, 28 January 1915). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, John, Elena, Maud, Charles H., and Frank A., in U.S. Census (Carl, Adams County, Iowa, 1900). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kneller, John, Elena, Maud, and Frank A., in U.S. Census (Carl, Adams County, Iowa, 1910). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Lloyd Kneller” (obituary of a grandson of John Kneller and a son of Allen John Kneller). Casper, Wyoming: Star-Tribune, 23 November 1986.

- Miss Maud Kneller (announcement of the marriage and relocation to Canada of John Kneller’s daughter), in “Married”; and Frank Fiscus and wife (announcement of the return from Canada by John Kneller’s daughter and son-in-law), in “Southwest Carl.” Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 6 September 1911 and 7 September 1912.

- Mr. and Mrs. John Kneller (description of their return trips to Pennsylvania during the 1870s-1880s and in 1911). Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 23 September 1911 and 22 November 1911.

- Mr. and Mrs. John Kneller, in “Of Local Interest.” Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 24 June 1908.

- “Mrs. Griffin Funeral Set” (death and funeral accouncement of Laura (Kneller) Griffin, a daughter of John Kneller). Des Moines, Iowa: Des Moines Tribune, 21 August 1967.

- “Obituary” (obituary of Ellena (Huber) Kneller, the widow of John Kneller). Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 18 April 1935.

- Pottinger, Earl and Lois (a granddaughter of John Kneller and the daughter of Stella Belle (Kneller) Henry); and Henry, Stella (the mother of Lois Pottinger and a daughter of John Kneller), in U.S. Census (Clarenda, Page County, Iowa, 1950).Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Roster of the 47th P. V. Inf.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 26 October 1930.

- “Safe as ‘Frisky Colts,’ Says Woman ‘Flyer,’ 83.” Des Moines, Iowa: The Des Moines Register, 8 July 1930.

- Schmidt, Lewis G. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- “The History of the Forty-Seventh Regt. P. V.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Lehigh Register, 20 July 1870.

- “Veteran Association Reunion.” Corning, Iowa: Adams County Free Press, 17 September 1902.

- “What Is the Difference Between a Conestoga Wagon and a Prairie Schooner?” Montpelier, Idaho: National Oregon/California Trail Center, retrieved online 26 August 2025.

You must be logged in to post a comment.