Alternate Surname Spellings: Wild, Wilt

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania map, 1837 (excerpt showing Berks, Lebanon, Lehigh, Luzerne, Montgomery, Northampton, and Schuylkill counties, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain; click to enlarge).

Born in Berks County, Pennsylvania circa 1838, Frederick Wilt was a son of Pennsylvania native Mary Wilt (1802-unknown). In 1850, he resided in the Borough of Hamburg in Berks County with his mother and sister, Paulina Wilt, who had been born circa 1842. Also living with them was Pennsylvania native Catharina Weaver, who had been born circa 1767.

During the summer of that same year (1850), a series of heavy storms generated freshets that overwhelmed farms and towns along the Schuylkill River with flood waters on 18-19 July and 2 September, causing loss of life and significant damage to homes, farm crops, businesses, bridges, and roads in multiple communitites across Berks County.

As area residents continued to recover from those disasters, Frederick Wilt made the decision to embark on a new life by marrying Anna Nonnemacher (1837-1895). Following their wedding, which took place sometime during the mid-1850s, they welcomed the birth of a son, Preston Wilt, circa 1858.

Their relatively stable lives would soon be upended, however, as their nation descended into the darkness of disunion and civil war between late 1860 and early 1861. Employed as a cigarmaker in Berks County as the war continued to rage on into 1862, he did his best to keep a roof over the heads of his wife and son and put food on their dinner table each night.

But it soon became obvious that, if he did not enlist in the army, he would likely be drafted — a fate that would give him far less control over his future.

* Note: Researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story have not yet confirmed the name of Frederick Wilt’s father or data related to the death of Frederick’s mother. They currently theorize that Frederick’s sister, Paulina, may have been the Pauline Wilt who married 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer James Ritter, and would welcome any data from Wilt family descendants which might help to validate or invalidate this theory. (Please see our “Contact Us” section for details on how to communicate with us regarding your research.)

American Civil War

Briefly enrolled for military service in Harrisburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania as a private with Company H of the 5th Pennsylvania Militia from 11-24 September in 1862, twenty-four-year-old Frederick Wilt was oddly unsuccessful during his first attempt to enlist with one of the many infantry units from Pennsylvania that were mustering into the Army of the United States during the first years of the American Civil.

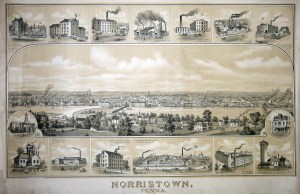

So, he tried again a year later — and succeeded. Re-enrolled at the Union Army’s recruiting depot in Norristown, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania on 2 December 1863, he was then officially mustered in there that same day as a private with Company G of the battle-hardened 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry; however, he did not actually begin to serve with his regiment, on site, until September of 1864.

Military records at that time described him as a twenty-five-year-old cigarmaker and resident of Berks County who was five feet, five and one-half inches tall with brown hair, hazel eyes and a dark complexion.

1864

First State Color, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (presented to the regiment by Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin, 20 September 1861; retired 11 May 1865, public domain).

Transported south to Virginia in early to mid-September 1864, Private Frederick Wilt finally connected with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, in person, at the regiment’s encampment outside of Berryville, Virginia on 18 September — the day before the Battle of Opequan unfolded and four days before the Battle of Fisher’s Hill was waged nearby. As a result of that timing, it is likely that he was not yet familiar enough with regimental combat procedures to take part in either of those key battles of Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign.

But he would most definitely have been pressed into service on 19 October 1864 during the Battle of Cedar Creek — an epic, but deadly fight for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

Battle of Cedar Creek

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, “Surprise at Cedar Creek,” captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle-pit positions, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

During the fall of 1864, Major-General Philip Sheridan began the first of the Union’s true “scorched earth” campaigns, starving the enemy into submission by destroying Virginia’s farming infrastructure. Viewed today through the lens of history as inhumane, the strategy claimed the lives of many innocent civilians, whose lives were uprooted or even cut short by the inability to find food or adequate shelter. This same strategy, however, almost certainly contributed to the further turning of the war in the Union’s favor during the Battle of Cedar Creek on 19 October 1864.

Successful throughout most of their engagement with Union forces at Cedar Creek, Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederates began peeling off in ever greater numbers as the battle wore on in order to search for food to ease their gnawing hunger, thus enabling Sheridan’s well-fed troops to rally and win the day.

From a military standpoint, it was an impressive show of the Union’s might. From a human perspective, it was both inspiring and heartbreaking. During the morning of 19 October, Early launched a surprise attack on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. Early’s men were able to capture Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles, all while pushing seven Union divisions back. According to historian Samuel P. Bates:

When the Army of West Virginia, under Crook, was surprised and driven from its works, the Second Brigade, with the Forty-seventh on the right was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat…. Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers as he rode rapidly past them – ‘Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!'”

Sheridan Rallying His Troops, Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

In response, Union troops staged a decisive counterattack that punched Early’s forces into submission. Afterward, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas, who, in 1892, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked” that day.

But the day proved to be a particularly difficult one for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. The regiment lost the equivalent of two full companies of men in killed, wounded and missing, as well as soldiers who were captured by Rebel troops and dragged off to prisoner of war (POW) camps, including the Confederates’ Libby Prison in Virginia, the notorious Salisbury Prison in North Carolina and the hellhole known as “Andersonville” in Georgia. Subjected to harsh treatment at the latter two, many of the 47th Pennsylvanians confined there never made it out alive. Those who did either died soon after their release, or lived lives that were greatly reduced in quality by their damaged health.

General J. D. Fessenden’s headquarters, U.S. Army of the Shenandoah at Camp Russell near Stephens City (now Newtown) in Virginia (Lieutenant S. S. Davis, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, December 31, 1864, public domain).

Following those major battles, Private Frederick Wilt and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered to march to Camp Russell near Winchester, where they rested and began the long recovery process from their physical and mental wounds. While still stationed at Camp Russell, Company G’s First Lieutenant George W. Hunsberger was honorably discharged from the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, on 30 November 1864, and was sent home to Pennsylvania.

In somewhat better shape after their most recent combat experience, Private Wilt and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians received new orders, directing them to pack up their belongings and depart for outpost and railroad guard duties at Camp Fairview in Charlestown, West Virginia. They headed out into a driving snowstorm just five days before Christmas.

1865 — 1866

Still stationed at Camp Fairview in West Virginia as the New Year of 1865 dawned, members of the regiment continued to patrol and guard key Union railroad lines in the vicinity of Charlestown, while other 47th Pennsylvanians chased down Confederate guerrillas who had made repeated attempts to disrupt railroad operations and kill soldiers from other Union regiments.

Assigned with their regiment to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah in February 1865, Privates Frederick Wilt and John Kneller were promoted to the rank of corporal on 1 February. They and their fellow 47th Pennsylvanians then continued to perform their guerrilla-fighting duties until late March, when they were ordered to head back to Washington, D.C., by way of Winchester and Kernstown, Virginia.

Joyous News and Then Tragedy

Spectators gather for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, beside the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half-staff after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

As April 1865 opened, the battles between the Army of the United States and the Confederate States Army intensified, finally reaching the decisive moment when the Confederate troops of General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox on 9 April.

The long war, it seemed, was finally over. Less than a week later, however, the fragile peace was threatened when an assassin’s bullet ended the life of President Abraham Lincoln. Shot while attending an evening performance of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre on 14 April 1865, the president died from his head wound at 7:22 a.m. the next morning.

Shocked, and devastated by the news, which was received at their Fort Stevens encampment, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were given little time to mourn their beloved commander-in-chief before they were ordered to grab their weapons and move into the regiment’s assigned position, from which it helped to protect the nation’s capital and thwart any attempt by Confederate soldiers and their sympathizers to re-ignite the flames of civil war that had finally been stamped out.

So key was their assignment that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were not even allowed to march in the funeral procession of their slain leader. Instead, they took part in a memorial service with other members of their brigade that was officiated by the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental chaplain, the Reverend William D. C. Rodrock.

Unidentified Union infantry regiment, Camp Brightwood, Washington, D.C., circa 1865 (public domain).

Present-day researchers who read letters sent by 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers to family and friends back home in Pennsylvania during this period, or post-war interviews conducted by newspaper reporters with veterans of the regiment in later years, will learn that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were collectively heartbroken by Lincoln’s death and deeply angry at those whose actions had culminated in his murder. Researchers will also learn that at least one member of the regiment, C Company Drummer Samuel Hunter Pyers, was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train, while other members of the regiment were assigned to guard duty at the prison where the key assassination conspirators were being held during the early days of their imprisonment and trial, which began on 9 May 1865. The regiment was headquartered at Camp Brightwood during this period.

Attached to Dwight’s Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were permitted to march in the Union’s Grand Review of the National Armies, which took place in Washington, D.C. on 23 May.

Reconstruction

Ruins of Charleston, South Carolina as seen from the Circular Church, 1865 (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

On their final southern tour, Corporal Frederick Wilt and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers served in Savannah, Georgia in early June. Assigned again to Dwight’s Division, this time they were attached to the 3rd Brigade, Department of the South. Relieving the 165th New York Volunteers in July, they quartered in the former mansion of the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury. Duties for the 47th during this phase were Provost (military police) and Reconstruction-related, including rebuilding railroads and other key segments of the region’s battered infrastructure.

Beginning on Christmas day of that year, Corporal Wilt and the majority of 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers, finally began to honorably muster out for the final time in Charleston, South Carolina — a process which continued through early January. Following a stormy voyage home, they disembarked in New York City. Weary, but eager to see their loved ones, they were transported to Philadelphia by train where, at Camp Cadwalader between 9-11 January 1866, they were officially given their honorable discharge papers.

By the time of that honorable discharge, Corporal Wilt had only received eighty of the two hundred and twenty-two dollars in bounty funds that he had been promised to him by the federal government as an incentive for enlisting with the Army of the United States. He was also still owed thirteen dollars and eighty-five cents from his clothing allowance for his “Union blues.” He eventually received his due when he was given his final pay — minus the one dollar and fifty cents that he still owed the sutler for food and other supplies that he had purchased to make his days as a soldier more bearable.

Return to Civilian Life

Center Square at 7th Street (Allen House Hotel at right; Allentown Bank and Board of Trade, looking north, top), Allentown, Pennsylvania 1876 (public domain).

Following his honorable discharge from the military, Frederick Wilt returned home to his wife, Anna, and their son, Preston. By 1870, he was employed as a carpenter, and was living with his wife and son in the Third Ward of the Borough of Wilkes-Barre in Luzerne County. (That borough then officially became a city the following year.)

Sometime afterward, he found work as a laborer in the city of Allentown in Lehigh County, and relocated there with his wife, Anna (Nonnemacher) Wilt.

* Note: Researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story have not yet determined what happened to Frederick Wilt’s son, Preston, but are continuing to search for additional data.

Still residing in Allentown as of 1890 when that year’s special federal census of veterans and their wives/widows was conducted, Frederick Wilt was living the life of an average Pennsylvanian, and continued to do so until tragedy struck his household.

On 7 June 1895, his wife, Anna (Nonnemacher) Wilt, fell down the stairs in their home in Allentown while carrying a lighted oil lamp. The burns that she sustained were fatal. In her late fifties at the time of her death, she was subsequently laid to rest at the Union-West End Cemetery in Allentown.

Illness, Death and Interment

Main Building, National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Hampton, Virginia, circa 1902 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

A grief-stricken widower who was ailing with rheumatism that was directly attributable to his military service with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in 1864, Frederick Wilt was admitted to the U.S. National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in Hampton, Virginia on 8 February 1896. His U.S. Civil War Pension rate at that time was eight dollars per month. Military records described him as a fifty-eight-year-old native of Berks County, Pennsylvania who was five feet, six inches tall with brown hair, hazel eyes and a light complexion.

Military headstone of Corporal Frederick Wilt, Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Hampton National Cemetery, Hampton, Virginia (public domain).

A resident of Allentown when he was admitted to the soldiers’ home, he had been working as a laborer, was a Protestant, and was unable to read or write English — which meant that his native language was most likely German or Pennsylvania Dutch.

Also ailing with hemiplegia during his final months, he was in his early sixties when he died at the National Soldiers’ Home in Hampton on 22 February 1900. Following funeral services, he was laid to rest at the Hampton National Cemetery in Hampton, Virginia.

At the time of his passing, Corporal Frederick Wilt had just two dollars and forty-five cents to his name. His next of kin was listed in records of the soldiers’ home as “J. Leidner, 411 Ridge, Allentown.”

Sources:

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Frederick Wilt, in Admissions Ledgers, U.S. National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (Hampton, Virginia, 1896-1900). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Frederick Wilt, in U.S. Census (“Special Schedule. — Surviving, Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, and Widows, etc.”: Allentown, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, 1890). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Grodzins, Dean and David Moss. “The U.S. Secession Crisis as a Breakdown of Democracy,” in When Democracy Breaks: Studies in Democratic Erosion and Collapse, from Ancient Athens to the Present Day (chapter 3). New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2024.

- “Mrs. Frederick Wilt” (description of the accidental death of Frederick Wilt’s wife, Anna (Nonnemacher) Wilt), in “State Snapshots.” Scranton, Pennsylvania: Scranton Tribune, 8 June 1895.

- “Roster of the 47th P. V. Inf.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 26 October 1930.

- Schmidt, Lewis G. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- “The History of the Forty-Seventh Regt. P. V.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Lehigh Register, 20 July 1870.

- Wilt, Frederick, in Civil War Muster Rolls (Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Wilt, Frederick, in Pennsylvania Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 (Company H, 5th Pennsylvania Militia and Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Wilt, Frederick, Anna and Preston, in U.S. Census (Wilkes-Barre, Third Ward, Luzerne County, 1870). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Wilt, Mary (mother and head of household), Frederic and Paulina; and Weaver, Catharina, in U.S. Census (Borough of Hamburg, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1850). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.