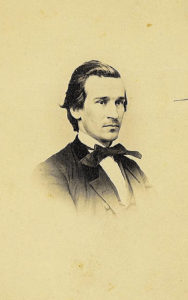

Private Samuel Transue, Company E, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, circa 1863 (used with permission, courtesy of Julian Burley).

“The late Mr. Transue was a splendid gentleman and was widely known especially in and near Lindsey where he resided so many years and where he was always an esteemed and respected resident of the community highly regarded by every one. He was a brave soldier, an excellent workman, honest and industrious, a man of exemplary habits and was spared to live out a long and well spent life.” — The Fremont Daily News, December 6, 1926

He was one of “the lucky ones,” a survivor of multiple American Civil War battles who somehow managed to survive under intense fire, again and again, to return home to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and begin life anew during the post-war Reconstruction Era.

A carpenter by trade, Samuel Transue not only helped to build new homes for members of his community, he helped to rebuild a shattered nation.

Formative Years

Delaware and Lehigh Rivers at Easton, Pennsylvania, 1844 (Augustus Kollner, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Born in Easton, Pennsylvania on 5 September 1833, Samuel Transue was a son of Jacob I. Transue (1807-1899) and Polly (Root/Roth) Transue. Baptized at Easton’s United Church of Christ on 21 December 1834, he grew to adulthood in that city.

In 1850, Samuel was still living in Easton with his parents and sisters, Louisa (1830-1914) and Anna, who were born, respectively, on 11 April 1830 and circa 1839. His father supported their family on the wages of a miller.

Sometime after the 1850 federal census was completed, however, the makeup of the Transue household changed when a decision was made by Samuel Transue’s older sister, Louisa, to marry a local tailor, Charles Hickman Yard. (Roughly a decade later, Yard, would play an increasingly important role in Samuel Transue’s life, effectively becoming his “boss” after both men entered military service.)

As the 1850s continued to unfold, Charles and Louisa Hickman Yard quickly began their own Easton-based family while the Transues continued on with their efforts to better their lives and those of their neighbors. By 1860, the Transue household in Easton’s West Ward included patriarch Jacob, matriarch Polly and siblings Samuel and Anna.

Their relatively stable, peaceful existence was shaken on 20 December 1860, however, by the shocking news that state leaders in South Carolina had done the unthinkable — they had set their state on the path to secession from the United States and had also convinced the leaders of other states across America’s Deep South to follow them into the darkness of disunion.

As the old year gave way to the new, one southern state after another tore the nation further and further apart: Mississippi (9 January 1861), Florida (10 January), Alabama (11 January), Georgia (19 January), Louisiana (26 January), and Texas (1 February).

In response, Northampton County residents came together to protest the actions of those southern states — launching massive demonstrations that were later described by the Reverend Uzal Condit in his book, History of Easton, Penn’a from the Earliest Times to the Present, 1739-1885. On 8 January 1861:

The National Guards, Citizens Artillery and Easton Jaegers paraded with full ranks during the afternoon, while at intervals ‘Poly’ Patier, with his six-pounder on Mount Jefferson, reminded the citizens who thronged the streets, how British ranks fell before the Kentucky rifles at New Orleans, and how the hero of that day, had in 1832, pledged his oath to hang the man who would attempt to dissolve the Union as high as Haman.

On 22 February, they protested again — this time as part of county-wide events honoring America’s first president, George Washington. According to Condit:

The clouds of disunion, gathering for some time, had become ominously black in the southern sky and gave every evidence of being about to burst in armed treason. This gave great significance to the celebrations in honor of the Father of his Country, and of that stern old patriot who had sworn by the Eternal that the Union must be preserved.

Day by day this feeling grew among Eastonians…. The mechanics and workingmen, the bone and somewhat every community, discussed the threatening news early and late, at their homes, in their shops and at the meetings of their societies.

The rising tension bore a unique form of fruit — resolutions by groups of average citizens that formally documented their concerns regarding the state of their nation. One such statement declared that:

The “election of Abraham Lincoln or any other man, to the office of President in a legal and constitutional manner, is not a fit or just cause for the dismemberment of this great and mighty republic.”

Another noted that Northampton County residents would view any secession as “revolution and treason — a means employed by traitors to destroy the inestimable blessings of liberty, which were bought by the blood of our forefathers and which are as dear to us as our own lives.”

While another stated that Northampton County residents were “opposed to making any concessions to those who are laboring to sever the bonds of our Union, by articles of secession, that would array brother against brother in hostile combat, that would trample in the dust the stars and stripes, the only true emblem of our national liberty and greatness, the pride of every true American, which has floated so long over our beloved country, and which has been acknowledged and honored by every nation and in every commercial port throughout the civilized world.”

American Civil War — Three Months’ Service

Inspired by that patriotic fervor, Samuel Transue became one of the earliest residents in Pennsylvania to respond to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers to defend the nation’s capital, following the fall of Fort Sumter to Confederate States troops in mid-April 1861. Following his enlistment in Easton, he traveled to the city of Harrisburg in Dauphin County, where he was officially mustered into military service on 18 April 1861 as a private with Company H of the 1st Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Also serving in that same regiment, but in a different unit, was Samuel’s brother-in-law, Charles H. Yard, who had been commissioned as the second lieutenant of Company C.

According to a brief biographical sketch of Samuel Transue’s life that is available at the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library and Museums at Spiegel Grove in Fremont, Ohio, the 1st Pennsylvania Volunteers “drew haversacks, canteens, guns and ammunition, and without uniforms started South. They made few stops before reaching the Shenandoah Valley where they remained until the expiration of their term of service.”

Following his regiment’s completion of its Three Months’ Service, Private Samuel Transue and his fellow 1st Pennsylvania Volunteers were sent back to Harrisburg, where they were officially mustered out on 19 July 1861.

Sometime around this same time, Samuel Transue and Celia Cooper welcomed the birth of a son, William Transue (alternate birth year: 1863).

American Civil War — Three Years’ Service

Knowing that the fight to preserve America’s Union was far from over, Samuel Transue opted to re-enlist with the Union Army. After re-enrolling in Allentown, Lehigh County on 11 August 1862, he officially re-mustered at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg on 10 September. Transported south to where his new comrades were stationed, he connected with his regiment from a recruiting depot in Beaufort, South Carolina on 14 October and was almost immediately subject to a baptism of fire when his regiment was ordered to disrupt military operations of the Confederate States of America by destroying a key Confederate railroad bridge near Pocotaligo, South Carolina on 22 October.

Military records at the time described him as being a twenty-seven-year-old carpenter from Easton who had been enrolled as a private with Company E of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

The Battle of Pocotaligo and Its Aftermath

According to Major-General Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel, commanding officer of the Army of the United States’ Department of the South, the Union Army soldiers who were assigned to undertake the destruction of the Pocotaligo Bridge were the:

Forty-seventh Pennsylvania, 600 men; Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania, 400 men; Fourth New Hampshire, 600 men; Seventh Connecticut, 500 men; Third New Hampshire, 480 men; Sixth Connecticut, 500 men; Third Rhode Island, 300 men; Seventy-sixth Pennsylvania, 430 men; New York Mechanics and Engineers, 250 men; Forty-eighth New York, 300 men; one section of Hamilton’s battery and 40 men; one section of the First Regiment Artillery, Company M, battery and 40 men, and the First Massachusetts Cavalry, 100 men. Making an entire force of 4,500 men.

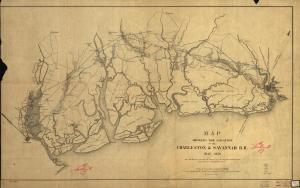

This 1856 map of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad shows the island of Hilton Head, South Carolina in relation to the towns of Beaufort and Pocotaligo (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain; click to enlarge).

The planning for the anticipated military action against the Confederacy was thorough, according to Mitchel’s post-engagement reports to his superiors, but was far less than that, according to his subordinate officers and the enlisted men who fought that terrible day.

Shortly after 12:01 a.m. on 22 October 1862, the combined task force of the Union’s army and navy sailed and steamed away from Hilton Head Island in South Carolina and headed for the village of Pocotaligo. The Paul Jones departed first, followed by the Ben Deford (towing flat-boats with artillery), the Conemaugh and Wissahickon, the Boston (towing flat-boats with artillery), the Patroon and Darlington, the Relief (a steam tug towing a schooner), and the Marblehead, Vixen, Flora, Water Witch, George Washington, and Planter. The flat-boats carried Union Artillery howitzers and/or light ambulances and supply wagons. Each of the 4,500 infantrymen was equipped with just one hundred rounds of ammunition (an estimate of the firepower that would be needed that would prove to be tragically inaccurate).

In addition to the Union troops, each of the largest ships carried a member of the U.S. Army’s Signal Corps to facilitate communications between the vessels, as well as an experienced ship pilot from the area who was well acquainted with the waterways they would be traveling.

Mother Nature, seemingly worried for the Union’s success, conjured up a smoky, hazy night with such poor visibility that leaders of the expedition soon had trouble communicating with each other. But their troop transports steamed on anyway, slowing progressing toward the mouth of the Pocotaligo River and their planned gathering spot at Mackay’s Point.

Their schedule was thrown off, however, when one of the Union ships ran aground, causing a three to four-hour delay that gave Confederate military leaders time to organize a “welcome party.”

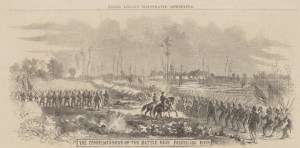

“The Commencement of the Battle near Pocotaligo River” (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, October 1862, public domain).

Completing just three of the eight miles they were told they must march to reach their target, the first wave of Union troops quickly realized just how heated and inhospitable that greeting would be as they began taking fire from highly skilled sharpshooters and heavily entrenched Confederate artillerymen. Straightening their backs, they stood up and began a valiant push, driving Confederates up and across the Pocotaligo River before destroying the railroad bridge their enemy had worked so hard to protect. But they were forced to waste precious ammunition and personal stamina to do so. At that point, according to Mitchel:

The march and fight continued from about 1 o’clock until between 5 and 6 o’clock in the afternoon. The officers and troops behaved in the most gallant manner. One bayonet charge was made over causeways with the most determined courage and with veteran firmness. The advance was made with caution, but with persistent steadiness, driving the enemy over a distance of more than 3 miles, and finally compelling him to seek safety by crossing the Pocotaligo River and the destruction of the bridge. The fight was continued on the banks of the Pocotaligo, but the coming on of night and the exhaustion of our ammunition, as well as the impossibility of crossing the river, rendered it necessary for the troops to return to their boats.

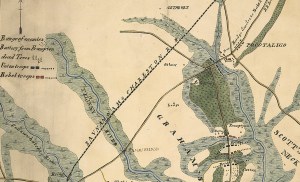

Excerpt from the U.S. Army map of the Pocotaligo-Coosawhatchie Expedition, 22 October 1862, showing the Caston and Frampton plantations in relation to the town of Pocotaligo, the Pocotaligo bridge and the Charleston & Savannah Railroad (public domain).

According to Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan, the commanding officer of the expedition (who was actually on site, as opposed to Mitchel), the Union expedition was, in truth, far more difficult and dangerous.

On advancing about 5 1/2 miles and debouching upon an open rolling country the rebels opened upon us with a field battery from a position on the plantation known as Caston’s. I immediately caused the First Brigade to deploy, and, bringing my artillery to the front, drove the rebels from this position. They, however, destroyed all small bridges in the vicinity, causing much delay in my advance. These, with the aid of the Engineer Corps, were reconstructed as we advanced, and I followed up the retreat of the rebels with all the haste practicable. I had advanced about 1 1/4 miles farther, when a battery again opened on us from a position on the plantation called Frampton. The rebels here had every advantage of ground, being ensconced in a wood, with a deep swamp in front, passable only by a narrow causeway, on which the bridge had been destroyed, while, on our side of the swamp and along the entire front and flanks of the enemy (extending to the swamps), was an impervious thicket, intersected by a deep water ditch, and passable only by a narrow road. Into this road the rebels threw a most terrific fire of grape shot, shell, canister, and musket balls, killing and wounding great numbers of my command. Here the ammunition for the field pieces fell short, and, though the infantry acted with great courage and determination, they were twice driven out of the woods with great slaughter by the overwhelming fire of the enemy, whose missiles tore through the woods like hail. I had warmly responded to this fire with the sections of First and Third U.S. Artillery and boat howitzers until, finding my ammunition about to fail, and seeing that any flank movement was impossible, I pressed the First Brigade forward through the thicket to the verge of a swamp, and sent the section of the First U.S. Artillery, well supported, to the causeway of the wood on the farther side, leaving a second brigade, with Colonel Brown’s command, the section of Third U.S. Artillery, and the boat howitzers as a line of defense in my rear. The effect of this bold movement was immediately evident in the precipitate retreat of the rebels, who disappeared in the woods with amazing rapidity. The infantry of the First Brigade immediately plunged through the swamp, (parts of which were nearly up to their arm-pits) and started in pursuit….

As that pursuit frantically continued, according to Brannan, his troops “arrived at that point where the Coosawhatchie road … runs through a swamp to the Pocotaligo Bridge.”

Here the rebels opened a murderous fire upon us from batteries of siege guns and field pieces on the farther side of the creek. Our skirmishers, however, advanced boldly to the edge of the swamp, and, from what cover they could obtain, did considerable execution among the enemy. The rebels, as I had anticipated, attempted a flank movement on our left, but for some reason abandoned it. The ammunition of the artillery here entirely failed, owing to the caissons not having been brought on, for the want of transportation from Port Royal, and the pieces had to be sent back to Mackay’s Point, a distance of 10 miles, to renew it.

The bridge across the Pocotaligo was destroyed, and the rebels from behind their earthworks continued on their only approach to it, through the swamp. Night was now closing fast, and seeing the utter hopelessness of attempting anything further against the force which the enemy had concentrated at this point from Savannah and Charleston, with an army of much inferior force, [that had not been sufficiently provisioned] with ammunition, and not having even sufficient transportation to remove the wounded, who were lying writhing along our entire route, I deemed it expedient to retire to Mackay’s Point, which I did in successive lines of defenses, burying my dead and carrying our wounded with us on such stretchers as we could manufacture from branches of trees, blankets, &c.

On 23 October 1862, the battered and bloody 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers returned to Hilton Head with other members of Brannan’s Union force. Just over a week later, several 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were appointed to the honor guard which served at the funeral of Major-General Mitchel, who had succumbed to complications from yellow fever.

On 15 November, Private Samuel Transue and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians received new orders. Directed to begin packing up their belongings, they were advised they would be heading to Florida, where the regiment would be divided roughly in half and assigned to garrison duties at either Fort Taylor in Key West or Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas.

Among those headed to Fort Taylor in mid-December were Private Samuel Transue and his E Company comrades.

1863

Also stationed at Fort Taylor with the men from Company E were the members of Companies A, B, C, G, and I of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Their time in sunny Florida would be no pleasure vacation, however; the regiment’s job was to defend a federal installation that leaders of the Confederacy were perpetually plotting to capture in order to establish a secure point of entry through which Confederate military units and businesses could send and receive cotton, food, tobacco, and other goods to and from foreign powers that were bent on destabilizing the United States.

In response to those threats, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers took turns on guard duty and received training on how to operate the various types of artillery that were positioned around the fort and across Key West. They took their assignment seriously, failing only when they were felled by typhoid fever, dysentery or bouts of chronic diarrhea that were caused by the poor quality of water available to them for drinking and bathing (or by diseases spreading insects).

Steadfastly dedicated to their respective assignments between mid-December 1862 and late February 1864, they were then ordered to move on — and move on they did, steaming into the pages of history as the only regiment from Pennsylvania to participate in the Union’s 1864 Red River Campaign across Louisiana.

1864

Steaming for New Orleans, Louisiana aboard the Charles Thomas on 25 February 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers from Companies B, C, D, I, and K arrived in Algiers (across the river from New Orleans) three days later, followed by the men from Companies E, F, G, and H on 1 March. (The members of Company A, a number of whom had been assigned to detached duty elsewhere in Florida, would ultimately reconnect with the regiment in Louisiana in early April.)

After disembarking and reconnecting in Algiers, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers hopped aboard a train, traveled to Brashear (now Morgan City), debarked and boarded a steamer there, which transported them through the Bayou Teche to Franklin, where they joined the Army of the United States’ Army of the Gulf, which was commanded by Major-General Nathaniel Banks. Attached to the 19th Army Corps, they were assigned to that corps’ 2nd Brigade, 1st Division.

Natchitoches, Louisiana (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 7 May 1864, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

From 14-26 March, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers passed through New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington en route to the top of the “L” in the L-shaped state. Heading first to Alexandria and Natchitoches, their ultimate goal was Shreveport and their assignment was to prevent the spread of both the Confederacy and the brutal practice of chattel slavery.

From 4-5 April 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry added to its roster of young Black soldiers when it enrolled five men who had been freed from enslavement in/near Natchitoches, Louisiana.

Often short on food and safe drinking water during their long, harsh-climate marches, multiple 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers fell ill along the way as they continued their trek northwest. On 7 April, the healthiest members of the regiment helped the weaker ones set up camp near the village of Pleasant Hill.

Map of key 1864 Red River Campaign locations, showing the battle sites of Sabine Cross Roads, Pleasant Hill and Mansura in relation to the Union’s occupation sites at Alexandria, Grand Ecore, Morganza, and New Orleans (excerpt from Dickinson College/U.S. Library of Congress map, public domain).

Resuming that trek the next day, they marched until mid-afternoon when they were briefly halted and then ordered to run toward a new danger. Rushed into the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads ahead of other 2nd Division regiments, they immediately faced intense rifle and cannon fire that felled sixty members of the regiment. The fighting waned only as darkness descended, and only when exhausted troops on both sides collapsed between their wounded and dead comrades.

Also known today as the Battle of Mansfield, it was the first of a series of Red River Campaign combat engagements that were fought across Louisiana, including the Battle of Pleasant Hill (9 April), the Affair at Monett’s Ferry (23 April), which enabled the Union Army to effect its crossing of the Cane River, and the Battle of Mansura near Marksville (16 May).

Researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story, however, have not yet been able to determine whether or not Private Samuel Transue actually took part in any of those battles. What is currently known is that he reportedly fell so ill during the Red River Campaign that he developed a chronic diarrhea condition that required prolonged treatment at one of the Union Army hospitals in New Orleans. Still ailing after that medical care, he was then awarded sick leave (via a military furlough) and sent home to Pennsylvania to have more time to recover. He then “rejoined his regiment nine months later at Winchester, Virginia.”

*Note: If the Hayes Library’s data is correct, then Private Samuel Transue may not only have missed a significant portion of the 47th Pennsylvania’s engagements during the 1864 Red River Campaign in Louisiana, he may also have missed part or all of the major engagements of Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign across Virginia, including the tide-turning Battle of Cedar Creek.

Following his return to duty with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry sometime during the fall of 1864, Private Samuel Transue discovered that he and his comrades were assigned to quarters at Camp Russell near Winchester, Virginia. They remained here from November through most of December, but were then ordered to pack up their belongings, yet again, in preparation for another move.

Five days before Christmas, they set out on foot, marching through a driving snowstorm for Camp Fairview in Charlestown, West Virginia. Their new job was to bring an end to guerilla attacks by Confederate troops and their civilian supporters that had been damaging Union railroad operations and supply distribution efforts in the region.

1865–1866

Still based at Camp Fairview as the New Year of 1865 dawned, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers continued their efforts to protect key railroad lines that were vital components of the federal government’s war strategy — duties that they continued to perform through the end of March.

According to The Lehigh Register, at that juncture, “The command was ordered to proceed up the valley to intercept the enemy’s troops, should any succeed in making their escape in that direction.” By 4 April 1865, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had made their way back to Winchester, Virginia, and were headed for Kernstown.

Five days later, they received word that General Robert E. Lee had surrendered the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox on 9 April 1865. The long war appeared to be over.

Spectators gather for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, beside the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half-mast following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

But it wasn’t. During the evening of 14 April, a night that was supposed to be a time of celebration for Washingtonians, a group of Confederate sympathizers attempted to reignite the flames of civil war by murdering President Abraham Lincoln and key members of his cabinet. Mortally wounded by a gunshot to his head, the president drew his last breath the following morning.

One of multiple Union Army regiments that were placed on alert in the wake of President Lincoln’s assassination, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was charged with defending the nation’s capital and ordered to make its way back to Washington, D.C.

Letters written to family and friends during this time and newspaper accounts published in subsequent years noted that at least one member of the regiment was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train while other members of the regiment were assigned to guard duty at the prison where the key conspirators in the assassination plot were being held during the early days of their imprisonment and trial. The regiment also participated in the Union’s Grand Review of the Armies, which took place from 23-24 May.

As the last sounds of cheers from the adoring crowds faded, many of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were informed by their superiors that their service was still needed to make real the hard-won peace by helping to rebuild segments of the nation’s shattered Deep South as America’s Reconstruction Era began to take shape.

But that group of re-builders would not include Private Samuel Transue, who had received word that, per General Orders No. 53, he would be honorably mustered out of service from the regiment’s base of operations at Camp Brightwood on 1 June 1865.

Return to Civilian Life

Following his honorable discharge from the military, Samuel Transue returned home to Easton, Pennsylvania and decided to marry for the second time. His new wife, Henrietta Cawley Keiber (1832-1908), was a native of Luzerne County and a daughter of Jacob and Susan (Sheiner) Keiber. Following their wedding in Luzerne County, Samuel and Henrietta Transue welcomed the birth of a daughter, Annie Transue, on 24 July 1869.

During the mid-1870s, he packed up his family and made his way west with his wife and daughter to Sandusky County, Ohio, where he continued to work as a carpenter. By 1875, he and his wife, Henrietta, where living with their daughter, Anna, in the Sandusky County hamlet of Lindsey — a scenario that continued through at least the early 1880s. Also living close at hand was Samuel Transue’s father, Jacob.

Sadly, Jacob did not live to witness the dawn of a new century. Following his death in Lindsey on 22 September 1899, he was laid to rest at the Lindsey Cemetery.

Subsequently widowed by his second wife in 1908, Samuel Transue was still employed as a house carpenter and living by himself in Lindsey in 1910 when that year’s federal census enumerator arrived on his doorstep. As he continued to age, however, he chose to live a different, more vibrant life at the home of his son, William, who was living as William A. Thomas (1861-1947), in Fremont, Ohio. That new life made him a contributing member of a group of family and friends who kept him active and sharp-minded, including William’s wife and children, and several of William’s grandchildren.

Those relationships became more and more important over time because, as he aged, Samuel Transue became increasingly frail due to his longtime battle with chronic diarrhea — uncomfortable and often embarrassing moments that were directly attributable to his wartime service.

In response to his physical decline, the United States government awarded Samuel Transue a U.S. Civil War Pension to help him secure the medical care he needed as a veteran who helped defend and protect the nation from enemies foreign and domestic.

Sadly, his was not the only Transue whose health was in decline. During the summer of 1914, he received word that his older sister, Louisa (Transue) Yard, had died in Easton, Pennsylvania from heart and kidney disease on 13 August. Married to, and widowed by, Samuel Transue’s former commanding officer in the 47th Pennsylvania, Captain Charles Hickman Yard, she was laid to rest beside her her hero-husband at the Easton Cemetery on 17 August. They had had a good, long life together, during which time they had raised three daughters and a son.

Still residing with his factory-laborer son, William A. Thomas, in Fremont, Ohio in 1920, Samuel Transue’s other household companions included William’s wife and children, Robert and Cecilia, as well as other assorted family members.

A New Milestone Reached

On 5 September 1923, Samuel Transue celebrated his ninetieth birthday — an achievement that received significant news coverage by The Fremont Messenger:

Samuel Transue, of 338 Morrison street, one of the oldest living residents of Fremont, quietly celebrated his 90th birthday anniversary Wednesday, Sept. 5, and received the congratulations of many of his friends on the occasion of his natal day. This pioneer is a native of Pennsylvania, who migrated to Ohio at an early day and in 1875 was a resident of Lindsey, Ohio. Mr. Transue is of French blood and a well-preserved man for his age. He was able to be down town Saturday to receive attention from his favorite barber and appears quite hale and hearty. Mr. Transue makes his home with his son, William A. Thomas, and is the grandfather of Robert (Red) Thomas, Fremont’s famous baseball player, who is going great in the Western association.

Clippings from western papers received in Fremont last week show that “Red” is playing utility on the crippled Okmulgee (Okla.) team and that his hitting and fielding are western sensations, home runs and triples featuring his work and three and four hits per day being his daily ration. One paper carried “Red’s” picture and gives him a special story. He’ll be in higher company next season, sure.

Injury, Death and Internment

A witness to to the best and worst of humanity throught out his long life, Samuel Transue was finally felled not by the rifle or cannon fire of an enemy weapon, but by an incident that was, and remains, all too common for aging Americans — a terrible fall that resulted in a badly broken bone.

Following the incident, which occurred on 12 November 1926, the ninety-three-year-old Civil War veteran fought his last fight as bravely as anyone ever could. According to The Fremont Messenger:

Samuel Transue, 93, of Morrison street, who makes his home with his son, W. H. Thomas, met with an accident at his home Friday afternoon that, owing to his advanced age, may prove fatal. The old gentleman, whose eyesight has been failing for several years, attempted to arise from his chair, being alone in the room at the time. In some manner unknown he fell to the floor breaking his left thigh bone. The aged man was found on the floor shortly after the accident by a member of the household, who hearing the noise of the fall rushed to the room, finding Mr. Transue, despite his failing eyesight was an active man for his age and is perhaps the oldest living resident of Fremont. The sad accident is said to be regretted as the unfortunate man was of a very keen mind and loved company which will now be denied him.

Mr. Transue is the grandfather of Robert (Red) Thomas, well known professional baseball player, whose career had been closely followed by the old gentleman who is a real baseball fan.

He died at the Fremont home of his son at 11:30 p.m. on 5 December 1926. Following funeral services there at 2:30 p.m. on 7 December, which were officiated by the Reverend W. M. Harford, pastor of the First United Methodist Church, Samuel Transue’s remains were brought home to Lindsey and laid to rest beside those of his second wife at the Lindsey Cemetery.

The Fremont Daily News described his passing as follows:

Samuel Transue, 93, many years a resident of Lindsey, Civil War veteran and one of the oldest pioneers in Sandusky county, died Sunday night at 11:30 at the home of his adopted son, William A. Thomas, 235 Morrison street.

The death of the aged Mr. Transue followed injuries suffered three weeks ago when he sustained a fall and suffered a broken leg. His age was against him and he failed to recover from the effects of the injuries. The funeral services will be held at the Thomas home Tuesday afternoon at 2:30 o’clock, conducted by the Rev. W. M. Harford, pastor of the First Methodist church. The remains will be taken to Lindsey for interment in the village cemetery beside the remains of his wife who died a number of years ago.

The late Mr. Transue was born in Easton, Pa., Sept. 5, 1833, and spent the earlier years of his long life there. When the Civil War broke out he enlisted as a volunteer in the 47th Pennsylvania Infantry and served to the end of the great conflict, taking part in the battles of Gettysburg [sic, incorrect data] and other noted engagements. After the war he came west and located in Lindsey where he resided more than fifty years, following his trade, that of carpenter. Following the death of his wife Mr. Transue made his home with his adopted son, Mr. Thomas and family, who tenderly cared for the aged gentleman and made his last years comfortable and happy. In addition to the one adopted son, Mr. Transue is survived by one sister whose address is not known and six grandchildren, one of whom is “Red” Thomas, Fremont’s well known professional ball player.

The late Mr. Transue was a splendid gentleman and was widely known especially in and near Lindsey where he resided so many years and where he was always an esteemed and respected resident of the community highly regarded by every one. He was a brave soldier, an excellent workman, honest and industrious, a man of exemplary habits and was spared to live out a long and well spent life.

* Note: Although newspapers reported that Samuel Transue had fought in the Battle of Gettysburg in July of 1863, this data was correct. Samuel Transue was a member of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, which was stationed in Florida at the time that battle was being waged.

Another of his obituaries, one that was published in the 6 December edition of the Fremont Messenger, gave a clue as to how this confusion may have occurred when it noted that Samuel Transue “was a wonderful raconteur of his tales of the early days and stories of the civil war….”

What Happened to Samuel Transue’s Family?

William Transue, the son of Samuel Transue and his first wife, Celia (Cooper) Transue, reportedly remained in Pennsylvania when Samuel relocated to Ohio after the war, and was still living with his grandparents at the time that the Hayes Library’s biographical sketch about Samuel Transue was written in 1885; however, closer examination of multiple sources reveals that William A. Thomas, the “adopted son” of Samuel Transue and his second wife, Henrietta (Keiber) Transue, was, in reality, William Transue, the son of Samuel Transue and his first wife, Celia. The name change was possibly made to ensure that William would be free to grow up without the stigma of an out-of-wedlock birth attached to his name.

As William A. Thomas, he truly did go on to live a long, full life. He and his wife, Mary Ann Thomas (1857-1924), had two children: Robert William Thomas (1889-1962) and Celia Thomas (1896-1946), who went on to marry Julius Herman Planet (1888-1954) in 1915, Wilson Shannon Steward (1896-1980) in 1922, and Orma Ashley Thompson (1911-1965).

A living bridge between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries who had known veterans of the American Civil War, World War I and World War II, William A. Thomas died in Ohio on 18 January 1947. Like his father before him, he was laid to rest at the Lindsey Cemetery.

Researchers are still working to determine what happened to Annie Transue, the daughter of Samuel Transue and his second wife, Henrietta (Keiber) Transue, and will post updates if and when new data becomes available. They have, however, made excellent progress in learning more about one of Samuel Transue’s grandchildren.

Robert “Red” Thomas, shown here during the early 1920s, became a professional baseball player during the World War I era and was signed by the Chicago Cubs in 1921 (Fremont Daily Messenger, Fremont, Ohio, 31 August 1927).

The most prominent member of the Transue family, Robert “Red” Thomas (1898-1962) grew up to be a professional baseball player. Born in Hargrove, Alabama on 25 April 1898, “Red” Thomas was the red-haired son of William and Mary Ann Thomas. He subsequently moved north with his family in 1913 when they relocated to the Sandusky County, Ohio community of Fremont.

According to the Fremont Daily Messenger, Red Thomas “received the rudiments of his baseball education on the sand lots of Fremont town and he started to blossom forth into an attraction during the old factory league days [there].” Educated through his junior high school years, he dropped out of his local public school system while still in his early teens in order to take a job with the Herbrand Corporation, which manufactured automobile suspension systems and which also sponsored a local baseball club.

After making a name for himself on the Herbrand team, he moved on to teams in Oklahoma and Arkansas. Propelled by his skill as a utility player who was successful at whatever position he was assigned to play, his star rose higher and higher as his achievements were reported by hometown, regional and nationwide newspapers.

In 1921, that star reached the highest of heights when he was scouted and signed by the Chicago Cubs. He subsequently played for the Cubs during the 1922 season and 1923 pre-season, but then developed a serious medical condition with boils that affected his vision to such a degree that he was ultimately sent back down to a minor league team.

That period of time also proved to be life-changing for an entirely different reason — his decision to marry and begin a family. On 27 December 1922, he wed Marie Louise Kaiser (1902-1950) at the Fremont, Ohio home of her mother. Their son, Robert William Thomas, Jr., was born in Augusta, Georgia on 5 August 1924 (the sixty-third anniversary of the date on which the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had been founded).

Attempting a comeback in 1927, he had some success, but ultimately decided to end his baseball career after twelve years of being one of the hard-charging “boys of summer.”

Employed by the Herbrand Corporation until it went out of business during the early 1960s, Red Thomas worked in a number of different jobs for the company, including as a drop forge inspector in 1930. Widowed when his wife passed away in February 1950, Red Thomas died at Fremont’s Memorial Hospital on 22 March 1962. Like his father and grandfather before him, he too was laid to rest at the Lindsey Cemetery.

Sources:

- “93 Years Old; Falls Breaking His Left Thigh: Samuel Transue: Fremont’s Oldest Living Resident, Injured.” Fremont, Ohio: The Fremont Messenger, 13 November 1926.

- “Aged Vet Dies in Fremont Home” (obituary of Samuel Transue). Sandusky, Ohio: Sandusky Register, 7 December 1926.

- “Another Civil War Veteran Is Mustered Out” (obituary of Samuel Transue). Fremont, Ohio: Fremont Messenger, 6 December 1926.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- “Camp Russell.” The Historical Marker Database, retrieved online 27 December 2023.

- Condit, A.M., Rev. Uzal. History of Easton, Penn’a from the Earliest Times to the Present, 1738-1885. Washington, D.C., West & Condit, 1885.

- Dyer, Frederick H. A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, p. 1589. Des Moines, Iowa: The Dyer Publishing Company, 1908.

- “Famous Ball Player’s Grand-Father Hale and Hearty at 90.” Fremont, Ohio: The Fremont Messenger, 8 September 1923.

- “Injuries Fatal to Aged Veteran” (obituary of Samuel Transue). Fremont, Ohio: The Fremont Daily News, 6 December 1926.

- Louisa T. Yard, in Death Certificates (file no.: 76859, registered no.: 372; date of death: 13 August 1914). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- Pidanick, Michael. “Lindsey’s Thomas was a major leaguer.” Fremont, Ohio: The News-Messenger, 29 July 1999.

- “‘Red’ Thomas Signs with Chicago Cubs.” Fremont, Ohio: Fremont Daily Messenger, 16 August 1921.

- “Samuel Transue,” in “Hardesty Sandusky County Ohio Civil War Sketches 1885.” Fremont, Ohio: Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library & Museums, 1885 (retrieved online, March 2021).

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- “Society” (announcement of the marriage of Red Thomas, Samuel Transue’s grandson). Fremont, Ohio: The Fremont Messenger, 28 December 1922.

- “The History of the Forty-Seventh Regt. P. V.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Lehigh Register, 20 July 1870.

- Thomas, Robert (Red). “I Played Baseball on the Herbrand Team in Old Industrial League.” Fremont, Ohio: Fremont Daily Messenger, 31 August 1927.

- Thomas, Robert Sr. (father), Marie, Robert Jr. (son), William (father of Robert Sr.); Kaiser, Louisa (mother-in-law) and Henry (brother-in-law), in U.S. Census (Fremont, Sandusky County, Ohio, 1930). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Thomas, W. A., Mary, Robert; Planter, Cecilia and Mary Ann; Fratter, James and Esibell; and Transue, Samuel, in U.S. Census (Fremont, Third Ward, Precinct C, Sandusky County, Ohio, 1920). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Transue, Jacob, Maria and Samuel, in Baptismal Records (First United Church of Christ, Easton, Northampton County, Pennsylvania, 1834). Easton, Pennsylvania: First United Church of Christ.

- Transue, Jacob, Mary, Louisa, Samuel, and Anna, in U.S. Census (Borough of Easton, Northampton County, Pennsylvania, 1850). Washington, D.C.: U.S.National Archives and Records Administration.

- Transue, Jacob, Mary, Samuel, and Anna, in U.S. Census (Borough of Easton, West Ward, Northampton County, Pennsylvania, 1860). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Transue, Samuel, in Civil War Muster Rolls (Company E, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Transue, Samuel, in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 (Company E, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Transue, Samuel, in U.S. Census (Special Schedule.–Surviving Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, and Widows, etc., Lindsey, Sandusky County, Ohio, 1890). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Transue, Samuel, in U.S. Civil War Pension General Index Cards (application no.: 577093, certificate no.: 435103, filed by the veteran, 15 June 1886). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Transue, Samuel, in U.S. Census (Lindsey, Sandusky County, Ohio, 1910). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Transue, Samuel and Henrietta, in U.S. Census (Washington, Sandusky County, Ohio, 1900). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Transue, Samuel, Henrietta and Anna, in U.S. Census (Hamlet of Lindsey, Sandusky County, Ohio, 1880). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.