Born in Utica, Oneida County, New York in January 1842, Edward Ludlow Clark, Sr. was a resident of the city of Easton in Northampton County, Pennsylvania. He was employed by a railroad company in northeastern Pennsylvania as America’s horrific civil war was winding down in 1865.

American Civil War

Edward L. Clark enrolled for military service in Easton, Pennsylvania on 28 January 1865, and mustered in there that same day as a private with Company E, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. He joined up with his regiment from a recruiting depot on 10 February — just in time to become an eyewitness to a period of history which still tugs at American’ heartstrings.

His regiment — the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers — having been assigned in February 1865 to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah, had been ordered to move, via Winchester and Kernstown, back to Washington, D.C., where they helped to defend the nation’s capital

* Note: By this point in his regiment’s history, the soldiers who had served with the 47th Pennsylvania since its founding in August 1861, had already helped to defend the nation’s capital in the fall of 1861 before helping to capture Saint John’s Bluff, Florida (1-3 October 1862), fighting in the bloody Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina (21-23 October 1862), strengthening the Union Army’s infrastructure in and around Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Key West and the Dry Tortugas, Florida (1862-1863), serving as the only Pennsylvania regiment involved in Union Major-General Nathaniel Banks’ Red River Campaign across Louisiana (March to June 1864), fighting at Snicker’s Gap under Major-General David Hunter (mid-July 1864), and fighting in legendary Union Major-General Philip Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign, including at the Battles of Opequan and Fisher’s Hill (September 1864) and the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia (19 October 1864).

Spectators gather for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, beside the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half-staff following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

On 19 April 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were once again called upon to help to defend the nation’s capital — this time following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Encamped near Fort Stevens, they were given new uniforms and additional ammunition supplies.

Letters sent to family and friends back home during this time, and post-war newspaper interviews with veterans of the 47th Pennsylvania, indicate that at least one 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train while others may have guarded the key conspirators who were involved in the Lincoln assassination during the early days of their imprisonment and trial, which began on 9 May 1865. During this phase of duty, the regiment was headquartered at CampBrightwood.

Assigned to Dwight’s Division of the 2nd Brigade of the U.S. Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania Pennsylvanians also participated in the Union’s Grand Review on 23 May. Captain Levi Stuber of Company I also advanced to the rank of major with the regiment’s central staff during this time.

Reconstruction

Charleston, South Carolina as seen from Circular Church, 1865 (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

On their final southern tour, Company E and their fellow 47th Pennsylvanians served in Savannah, Georgia in early June. Assigned again to Dwight’s Division, this time they were attached to the 3rd Brigade, U.S. Department of the South.

Taking over for the 165th New York Volunteers in July, they quartered in Charleston, South Carolina at the former mansion of the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury. Duties at this time were largely provost (military police) and Reconstruction-related (rebuilding railroads and other key parts of the region’s infrastructure which had been damaged or destroyed during the long war).

Alleged to have deserted from 10 October 1865 to 10 December 1865, Private Edward L. Clark had been arrested, according to regimental muster rolls, but had then been returned to duty on 14 December 1865, without trial per Special Orders, No. 144, issued by U.S. Department of the South.

During his alleged period of desertion, all of his pay and other allowances were ordered stopped.

Finally, beginning on Christmas day of that year, the majority of the men of Company E, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers, including Private Edward L. Clark, began to muster out at Charleston, South Carolina, a process which continued through early January. (Two 1898 soldiers’ home ledger entries for Private Clark of E Company confirm that he was discharged with his regiment at Charleston, South Carolina on 25 December 1865 per General Orders of the U.S. War Department and U.S. Army’s Department of the South.)

After a stormy voyage home, the soldiers of the 47th Pennsylvania disembarked in New York City. The weary men were then transported to Philadelphia by train where, at Camp Cadwalader on 9 January 1866, the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers were officially given their discharge papers.

Return to Civilian Life

Following his discharge from the military, Edward L. Clark headed north. In 1866, he wed Louisa Swinton Shannon (1844-1913). Born in Pennsylvania on 10 June 1844, she was the daughter of David and Catherine (Pope) Shannon. Together, they welcomed to the world daughter Catherine Pope Clark on 2 August 1866. (Catherine would later wed Charles Arthur Fahl, a native of Pennsylvania who had been born in July 1863, and have seven children of her own.)

Nearly three years later, daughter Annie May Clark opened her eyes in Northampton County for the first time on 3 June 1869. (Annie May would later wed Joseph Bell, a native of Pennsylvania who had been born in October 1876.)

Sons Edward Ludlow Clark, Jr. and Samuel Nelson Clark, arrived at the Clark home in Easton on 27 February 1871 and 26 May 1873, respectively. A twin sister, Elsie Delcena Clark, was also born with Samuel that day in May 1873. Sons William Henry Clark and Charles Thomas followed on 13 May 1875 and 24 April 1890, respectively. William was born in Easton; Charles Thomas (known as “Tom”) was born in Mauch Chunk (now Jim Thorpe) in Carbon County, Pennsylvania.

War-related Disabilities and Later Life

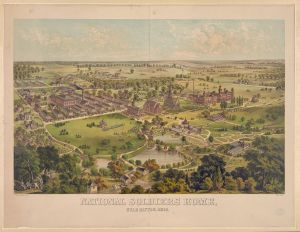

Main Building, National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Hampton, Virginia, circa 1902 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

According to the U.S. Veterans’ Schedule of 1890, Edward Clark was a resident of Easton, Northampton County, Pennsylvania. His U.S. Civil War Pension Index Card confirms that he was still a Pennsylvania resident as of 1891.

However, two U.S. Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers admissions ledger entries for him reveal even more regarding his later life. The first indicates that Edward was admitted to the Southern Branch of the soldiers’ home network at Hampton, Virginia on 31 August 1898. That date, though, appears to be a mistake committed by the individual completing Edward’s admissions paperwork. The admissions staffer had just entered the same admissions date on the prior page for a different soldier.

In addition, admissions personnel at the Central Branch soldiers’ home in Dayton, Ohio documented Edward’s original Hampton admissions date as 1 September 1898 when they readmitted Edward to the soldiers’ home system via the Dayton facility in 1907.

That Dayton ledger was also far more detailed in terms of information about Edward Clark’s medical condition. The Hampton ledger is still useful, however, because it documented Edward Clark’s city of birth (Utica, New York), as well as the reasons for his 1906 discharge from that home. (Conversely, Edward Clark was listed on the 1900 federal census as having been born in March 1845 in Pennsylvania, and was described as a son of parents who had been born in New York. That record is also useful because it noted that Edward Clark was married in 1866 — after the Civil War had ended.)

According to both soldiers’ home ledgers, Edward Clark suffered from rheumatism, was aged sixty-one at the time of admission in Hampton, Virginia, and was five feet, five and one-half inches tall with a sandy complexion, brown hair and gray eyes.

Still employed as a railroader, he was also a member of the Protestant faith. That Dayton ledger also noted that Edward Clark had been admitted in just “fair” condition, and was suffering from an old fracture of the nose, chronic naso-pharyngeal catarrh, cardiac hypertrophy, and chronic rheumatism.

Described as married, his nearest living relative was listed as: Mrs. Annie North Bell, No. 16, South 5th Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The Hampton soldiers’ home ledger listed his address subsequent to discharge as 2223 South 11th in Philadelphia, which matched the 1900 federal census listing showing an Edward Clark residing with his daughter, Annie Bell, and her husband, Joseph Bell, at the Bell home at 2223 South 11th Street in Philadelphia. Both Edward and Joseph were employed as salesmen at that time.

In addition, the Dayton soldiers’ home ledger documented that Edward Clark had been readmitted to the Central Branch (Dayton, Ohio) on 19 December 1907, where he remained until 1 December 1908.

Readmitted on 7 August 1909 to a third soldiers’ home — in Bath, Steuben County, New York, he was treated there for cardiac hypertrophy. That ledger entry also noted that Edward Clark had begun ailing with that condition sometime after the end of the American Civil War.

His occupation was listed as “Pedlar”; his wife was listed as Louisa S. Clark of 112 N. Main in Utica, New York.

* Note: Edward Clark’s wife, Louisa (Shannon) Clark, preceded him in death. Following her passing in Mauch Chunk (now Jim Thorpe), Carbon County, Pennsylvania on 9 May 1913, she was interred at the Easton Cemetery in Easton, Northampton County.

Although the soldier’s home ledger entry for Edward Clark described above provided no discharge date, it did indicate that he died from endocarditis on 26 December 1921 while residing at the soldiers’ home in Bath, New York. (A 1920 federal census listing also confirmed that he was a resident of that home in 1920.)

Edward Clark was subsequently interred at Hay’s Cemetery (plot C45) in Easton, Northampton County, Pennsylvania. His Pennsylvania Veteran’s Burial Index Card stated that no gravestone exists.

Sources:

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Civil War Veterans’ Card File. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Historical Registers of National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (Microfilm Publication M1749) and Records of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (Record Group 15) for the following soldiers’ homes: Southern Branch/Hampton, Virginia; Central Branch/Dayton, Ohio; and Bath, New York. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Pennsylvania Veteran’s Burial Index Card. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Department of Military and Veterans Affairs, 1939.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- U.S. Census (1900, 1920). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- U.S. Civil War Pension Index (application no.: 1071263; certificate no.: 782599; filed from Pennsylvania by the veteran and his attorney, W.V. Sickel, on 16 November 1891). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- U.S. Veterans’ Schedule (1890). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.