Perry County Courthouse, New Bloomfield, Pennsylvania (circa 1860s, Hain’s History of Perry County, 1922, public domain).

Born in June 1835 (alternate birth year 1842), Daniel S. Zook was a farmer residing in Bloomfield, Perry County, Pennsylvania during the outbreak of the Civil War. Like many of his fellow soldiers, he fought hard to preserve America’s Union and, after performing his duties to the best of his ability, returned home to the great Keystone State where he resumed life as “a regular guy.”

A leader in his community’s church, he would also work briefly as his town’s postmaster — but only after long and difficult service which repeatedly put his life at risk.

American Civil War

Daniel S. Zook enrolled for military service at the age of twenty on 9 August 1862 at Elliotsburg, Perry County, Pennsylvania, and mustered in for duty as a private with Company D, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County on 15 August 1862. The remarks section of his entry in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives indicates that he connected with his regiment via a recruiting depot on 11 September 1862.

He could not have known it at the time, but he was entering service with the 47th Pennsylvania just in time to participate in his regiment’s first serious combat experience.

Earthworks surrounding the Confederate battery atop Saint John’s Bluff along the Saint John’s River in Florida (J. H. Schell, public domain).

Sent from their base camp in South Carolina on an expedition to Florida at the end of September 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers participated with other Union regiments in the capture of Saint John’s Bluff from 1 to 3 October. Led by Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan, a fifteen-hundred-plus Union force disembarked at Mayport Mills and Mount Pleasant Creek from troop carriers guarded by Union gunboats. Taking point, the 47th led the 3rd Brigade through twenty-five miles of dense, pine forested swamps populated with deadly snakes and alligators. By the time the expedition ended, the brigade had forced the Confederate Army to abandon its artillery battery atop Saint John’s Bluff, and had paved the way for the Union to occupy the town of Jacksonville, Florida.

In the midst of this expedition, the regiment broke new ground when, from 5-15 October 1862, several of its officers completed the paperwork which enabled a teenager and several young to middle-aged Black men to enroll as members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ F Company. After being freed by the regiment from plantations near Beaufort, South Carolina, these had volunteered to enlist with the regiment. Initially assigned to kitchen duties, they were officially mustered in for duty with the regiment as Cooks and Under-Cooks at Morganza, Louisiana in June 1864. More men of color would continue to be added to the 47th Pennsylvania’s rosters in the weeks and years to come.

Highlighted version of the U.S. Army map of the Coosawhatchie-Pocotaligo Expedition, 22 October 1862 (public domain).

From 21-23 October, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman H. Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, the 47th engaged Confederate forces in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina. Landing at Mackay’s Point, the men of the 47th were placed on point once again, but they and the 3rd Brigade were less fortunate this time.

Harried by snipers en route to the Pocotaligo Bridge, they met resistance from an entrenched, heavily fortified Confederate battery which opened fire on the Union troops as they entered an open cotton field. Those headed toward higher ground at the Frampton Plantation fared no better as they encountered artillery and infantry fire from the surrounding forests.

The Union soldiers grappled with the Confederates where they found them, pursuing the Rebels for four miles as they retreated to the bridge. There, the 47th relieved the 7th Connecticut. But the enemy was just too well armed. After two hours of intense fighting in an attempt to take the ravine and bridge, the 47th Pennsylvanians were forced by depleted ammunition to withdraw to Mackay’s Point. Losses for the 47th were significant. Two officers and eighteen enlisted men died; two officers and an additional one hundred and fourteen enlisted men were wounded.

On 23 October, the 47th Pennsylvania returned to Hilton Head where, a week later, several of its members were assigned to duty as the funeral Honor Guard for Major-General Ormsby M. Mitchel, the commander of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps and Department of the South who had succumbed to yellow fever on 30 October. (The Mountains of Mitchel, a part of Mars’ South Pole discovered by Mitchel in 1846 while working as a University of Cincinnati astronomer, and Mitchelville, the first Freedmen’s town created after the Civil War, were both later named for him.)

1863

Fort Jefferson, Dry Torguas, Florida (circa 1934, C. E. Peterson, photographer, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

By 1863, Private Daniel Zook and his fellow D Company soldiers were once again based with the 47th Pennsylvania in Florida. Having been ordered back to Key West on 15 November of 1862, the early part of 1863 was spent guarding federal installations in Florida as part of the 10th Corps, Department of the South.

Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I garrisoned Fort Taylor in Key West while Companies D, F, H, and K garrisoned Fort Jefferson in Florida’s Dry Tortugas. Men from the 47th were also sent on skirmishes and to Fort Myers, which had been abandoned in 1858 after the third U.S. war with the Seminole Indians.

As before, disease was a constant companion and foe.

But the members of Company remained at Fort Jefferson for just over five months. On 16 May, they were marched back to the wharf at Fort Jefferson, where they climbed aboard yet another ship — this time to return to Fort Taylor, where they resumed garrison duties under the command of Colonel Tilghman H. Good.

1864

On 25 February 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers set off for a phase of service in which the regiment would truly make history. Steaming in two groups for New Orleans, the 47th Pennsylvania’s arrived at Algiers, Louisiana on 28 February and 1 March.

Transported by train to Brashear City (now Morgan City), they subsequently hopped aboard another steamer, and were taken to Franklin via the Bayou Teche. Joining the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the U.S. Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry became the only regiment from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks.

From 14-26 March, the 47th passed through New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington while en route to Alexandria and Natchitoches. Often short on food and water, the regiment encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day, marching until mid-afternoon.

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division, sixty members of the 47th were cut down on 8 April during the volley of fire unleashed during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads. The fighting waned only when darkness fell. Exhausted, those who were uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded and the dead. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate Major-General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner and son of Zachary Taylor, former president of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault, during what has since become known as the Battle of Pleasant Hill.

Casualties were once again severe. Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander was nearly killed, and the regiment’s two color-bearers, both from Company C, were also wounded while preventing the American flag from falling into enemy hands. Private Ephraim Clouser of Company D was shot in his right knee and captured by Confederate troops. Corporal Isaac Baldwin was also wounded, but avoided a similar fate. Others from the 47th who were also captured, were force marched roughly one hundred and twenty-five miles to Tyler, Texas, where they were confined to Camp Ford, the largest Confederate prison west of the Mississippi River. Held as prisoners of war (POWs), several died. Others managed to survive until they were released during prisoner exchanges beginning in July.

Meanwhile, as the captured 47th Pennsylvanians were being spirited away to Camp Ford, their comrades were carrying out orders from senior Union Army leaders to head for Grand Ecore, Louisiana. Encamped there from 11-22 April, they engaged in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications.

They then moved back to Natchitoches Parish on 22 April. While en route, they were attacked again, this time, at the rear of their retreating brigade, but they were able to end the encounter quickly and move on to reach Cloutierville at 10 p.m. that same night (after a forty-five-mile march).

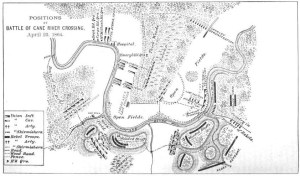

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were stationed just to the left of the “Thick Woods” with Emory’s 2nd Brigade, 1st Division as shown on this map of Union troop positions for the Battle of Cane River Crossing at Monett’s Ferry, Louisiana, 23 April 1864 (Major-General Nathaniel Banks’ official Red River Campaign Report, public domain).

The next morning (23 April), episodic skirmishing quickly roared into the flames of a robust fight. As part of the advance party led by Union Brigadier-General William Emory, the 47th Pennsylvanians took on the Confederate cavalry of Brigadier-General Hamilton P. Bee in the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry” or the “Cane River Crossing”).

Responding to a barrage from the Confederate artillery’s twenty-pound Parrott guns and raking fire from enemy troops positioned near a bayou and atop a bluff, Brigadier-General Emory directed one of his brigades to keep Bee’s Confederates busy while sending two other brigades to find a safe spot for the Union force to cross the Cane River. As part of the “beekeepers,” the 47th Pennsylvania supported Emory’s artillery.

Meanwhile, additional troops under Smith’s command, attacked Bee’s flank to force a Rebel retreat, and then erected a series of pontoon bridges that enabled the 47th Pennsylvania and other Union troops to make the Cane River Crossing by the next day. As the Confederates retreated, they torched their own food stores, as well as the cotton supplies of their fellow southerners. In a letter penned from Morganza, C Company’s Henry Wharton described what had happened:

Our sojourn at Grand Ecore was for eleven days, during which time our position was well fortified by entrenchments for a length of five miles, made of heavy logs, five feet high and six feet wide, filled in with dirt. In front of this, trees were felled for a distance of two hundred yards, so that if the enemy attacked we had an open space before us which would enable our forces to repel them and follow if necessary. But our labor seemed to the men as useless, for on the morning of 22d April, the army abandoned these works and started for Alexandria. From our scouts it was ascertained that the enemy had passed some miles to our left with the intention of making a stand against our right at Bayou Cane, where there is a high bluff and dense woods, and at the same attack Smith’s forces who were bringing up the rear. This first day was a hard one on the boys, for at 10 o’clock at night they made Cloutierville, a distance of forty-five miles. On that day the rear was attacked which caused our forces to reverse their front and form in line of battle, expecting too, to go back to the relief of Smith, but he needed no assistance, sending word to the front that he had ‘whipped them, and could do it again.’ It was well that Banks made so long a march on that day, for on the next we found the enemy prepared to carry out their design of attacking us front and rear. Skirmishing commenced early in the morning and as our columns advanced he fell back towards the bayou, when we soon discovered the position of their batteries on the bluff. There was then an artillery duel by the smaller pieces, and some sharp fighting by the cavalry, when the ‘mule battery,’ twenty pound Parrott guns opened a heavy fire, which soon dislodged them, forcing the chivalry to flee in a manner not at all suitable to their boasted courage. Before this one cavalry, the 3d Brigade of the 1st Div., and Birges’ brigade of the second, had crossed the bayou and were doing good service, which, with the other work, made the enemy show their heels. The 3d brigade done some daring deeds in this fight, as also did the cavalry. In one instance the 3d charged up a hill almost perpendicular, driving the enemy back by the bayonet without firing a gun. The woods on this bluff was so thick that the cavalry had to dismount and fight on foot. During the whole of the day, our brigade, the 2d, was supporting artillery, under fire all the time, and could not give Mr. Reb a return shot.

While we were fighting in front, Smith was engaged some miles in the rear, but he done his part well and drove them back. The rebel commanders thought by attacking us in the rear, and having a large face on the bluffs, they would be able to capture our train and take us all prisoners, but in this they were mistaken, for our march was so rapid that we were on them before they had thrown up the necessary earthworks. Besides they underrated the amount of our artillery, calculating from the number engaged at Pleasant Hill. The rebels say ‘it seems as though the Yankees manufacture, on short notice, artillery to order, and the men are furnished with wings when they wish to make a certain point.’

The damage done to the Confederate cause by the burning of cotton was immense. On the night of the 22d our route was lighted up for miles and millions of dollars worth of this production was destroyed. This loss will be felt more by Davis & Co., than several defeats in this region, for the basis of the loan in England was on the cotton in Louisiana.

After the rebels had fled from the bluff the negro troops put down the pontoons, and by ten that night we were six miles beyond the bayou safely encamped. The next morning we moved forward and in two days were in Alexandria. Johnnys followed Smith’s forces, keeping out of range of his guns, except when he had gained the eminence across the bayou, when he punished them (the rebs) severely.

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” in reference to Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, the officer overseeing its contruction, this timber dam built near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 faciliated Union gunboat passage along the Red River (public domain).

Having finally reached Alexandria on 26 April, they learned they would remain at their latest new camp for at least two weeks. Placed temporarily under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, they were assigned yet again to the hard labor of construction work, helping to erect “Bailey’s Dam,” a timber structure that was designed to enable Union Navy gunboats to safely navigate the fluctuating waters of the Red River. According to Wharton:

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gun boats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people will eat), so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the iron clads down the river. After a great deal of labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic, chute], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’ The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gun boat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

Continuing their march, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers headed toward Avoyelles Parish. According to Wharton:

On Sunday, May 15th, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of the Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad where with the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. – We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed in line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired, and we advanced ’till dark, when the forces halted for the night with orders to rest on their arms. – ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee.

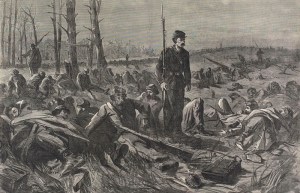

“Sleeping on Their Arms” by Winslow Homer (Harper’s Weekly, 21 May 1864).

“Resting on their arms,” (half-dozing, without pitching their tents, and with their rifles right beside them), they were now positioned just outside of Marksville, on the eve of the 16 May 1864 Battle of Mansura, which unfolded as follows, according to Wharton:

Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, they reached Missoula [sic, Mansura], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic, maneuvering] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic, were] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain correctly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport [sic, Simmesport] on the Achafalaya [sic, Atchafalaya] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over. – The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of the army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic, there] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.

Union Army base at Morganza Bend, Louisiana, circa 1863-1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Continuing on, the surviving members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry marched for Simmesport and then Morganza, where they made camp again. While encamped there, the nine formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the regiment in Beaufort, South Carolina (October 1862) and Natchitoches, Louisiana (April 1864) were officially mustered into the regiment between 20-24 June 1864.

The regiment then moved on and arrived in New Orleans in late June. On 4 July, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers received orders to return to the East Coast. Three days later, they began loading their men onto ships, a process that unfolded in two stages. Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I boarded the U.S. Steamer McClellan on 7 July and steamed away that day, while the members of Companies B, G and K remained behind, awaiting transport. (The latter group subsequently departed aboard the Blackstone, weighing anchor and sailing forth at the end of that month.)

As a result of this twist of fate, the 47th Pennsylvania’s “early travelers” had the good fortune to have a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln on 12 July 1864. They then took part in the mid-July Battle of Cool Spring near Snicker’s Gap, Virginia.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Halltown Ridge, looking west with “old ruin of 123 on left. Colored people’s shanty right,” where Union troops entrenched after Major-General Philip Sheridan took command of the Middle Military Division, 7 August 1864 (photo/caption: Thomas Dwight Biscoe, 2 August 1884, courtesy of Southern Methodist University).

Attached to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah beginning in August, the opening days of September saw the departure of several 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers who had served honorably, including Company D’s Captain Henry Woodruff, First Lieutenant Samuel Auchmuty, Sergeants Henry Heikel and Alex Wilson, and Corporals Cornelius Stewart and Samuel A. M. Reed. All mustered out 18 September 1864 upon expiration of their service terms. At least one of those departures—that of Sergeant Henry Heikel—might have been prevented had senior military leaders been more responsive to regimental advancement requests. According to historian Lewis Schmidt:

On Tuesday [9 August 1864], the 47th prepared to resume its march, this time from Halltown back to Middletown where the regiment arrived on Friday. Letters from both Col. Good and Capt. Gobin to the Governor and the Adjutant General of Pa. were written regarding promotions on this date from ‘In the field near Halltown’. In Company D, 54 of the non-commissioned officers and Privates signed a letter to the Governor’s office requesting that Sgt. Henry Heikel be promoted to Captain and Cpl. George W. Clay to Lieutenant. They were unsuccessful and this time, and other more senior men would be promoted to these positions. Sgt. Heikel would muster out the following month at the expiration of his term, and Cpl. Clay would eventually attained the rank of 1st Lieutenant on June 2, 1865.

And experienced, battle-tested leaders would be needed in the days and weeks ahead because those members of the 47th who did opt to remain on duty were about to engage in their regiment’s greatest moments of valor. The first significant test of this duty phase came during the first week of September as the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers fought in the Battle of Berryville from 3-4 September, and then engaged in related post-battle skirmishes with the enemy over subsequent days.

Battles of Opequan and Fisher’s Hill — September 1864

Together with other regiments under the command of Union Major-General Philip H. (“Little Phil”) Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, commander of the 19th Corps, the members of Company D and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers helped to inflict heavy casualties on Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate forces during the Battle of Opequan (also spelled as “Opequon” and referred to as “Third Winchester”). The battle is still considered by many historians to be one of the most important during Sheridan’s 1864 campaign; the Union’s victory here helped to ensure the reelection of President Abraham Lincoln.

The 47th Pennsylvania’s march toward destiny at Opequan began at 2 a.m. on 19 September 1864 as the regiment left camp and joined up with others in the Union’s 19th Corps. After advancing slowly from Berryville toward Winchester, the 19th Corps bogged down for several hours with the massive movement of Union troops and supply wagons, enabling Early’s men to dig in. As a result, upon reaching the Opequan Creek, Sheridan’s men came face to face with the Confederate Army commanded by Early.

The fighting, which began in earnest at noon, was long and brutal. The Union’s left flank (6th Corps) took a beating from Confederate artillery stationed on high ground.

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union Army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces, Battle of Opequan, 19 September 1864 (Kurz & Allison, circa 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania and the 19th Corps were directed by General William Emory to attack and pursue Major General John B. Gordon’s Confederate forces. Some success was achieved, but casualties mounted as another Confederate artillery group opened fire on Union troops trying to cross a clearing. When a nearly fatal gap began to open between the 6th and 19th Corps, Sheridan sent in units led by Brigadier-Generals Emory Upton and David A. Russell. Russell, hit twice — once in the chest, was mortally wounded. The 47th Pennsylvania then opened its lines long enough to enable the Union cavalry under William Woods Averell and the foot soldiers of General George Crook to charge the Confederates’ left flank.

The 19th Corps, with the 47th in the thick of the fighting, stood its ground and finally began pushing the Confederates back, prompting Early’s “grays” to retreat. Leaving twenty-five hundred wounded behind, the Rebels fell back to Fisher’s Hill (21-22 September), eight miles south of Winchester, and then to Waynesboro, following a successful early morning flanking attack by Sheridan’s “blue jackets” which outnumbered Early’s three to one. Afterward, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were sent out on skirmishing parties before making camp at Cedar Creek.

Moving forward, they and other members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers would continue to distinguish themselves in battle, but they would do so without two more of their respected commanders: Colonel Tilghman Good and Good’s second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel George Alexander, who mustered out 23-24 September upon expiration of their respective terms of service.

Fortunately, they were replaced by others equally admired both for temperament and their front line experience, including John Peter Shindel Gobin, Charles W. Abbott and Levi Stuber.

Battle of Cedar Creek, 19 October 1864

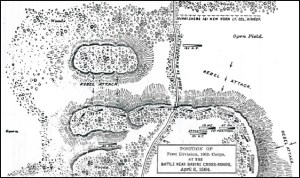

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, “Surprise at Cedar Creek,” captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle-pit positions, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

It was during the fall of 1864 that General Philip Sheridan began the first of the Union’s true “scorched earth” campaigns, starving the enemy into submission by destroying Virginia’s crops and farming infrastructure. Viewed through today’s lens of history as inhumane, the strategy claimed many innocents — civilians whose lives were cut short by their inability to find food. This same strategy, however, almost certainly contributed to the further turning of the war’s tide in the Union’s favor during the Battle of Cedar Creek on 19 October 1864. Successful throughout most of their engagement with Union forces at Cedar Creek, Early’s Confederate troops began peeling off in ever growing numbers to forage for food, thus enabling the 47th Pennsylvania and others under Sheridan’s command to rally.

From a military standpoint, it was another impressive, but heartrending day. During the morning of 19 October, Early launched a surprise attack directly on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. Initially, his men were able to capture Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles — all while pushing seven Union divisions back. According to Bates:

When the Army of West Virginia, under Crook, was surprised and driven from its works, the Second Brigade, with the Forty-seventh on the right, was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat…. Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions, without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers, as he rode rapidly past them – “Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!’”

Sheridan Rallying His Troops, Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

The Union’s counterattack, however, ultimately battered Early’s forces into submission. Afterward, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas who, in 1892, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked” that day. Bates described the 47th’s actions:

When the final grand charge was made, the regiment moved at nearly right angles with the rebel front. The brigade charged gallantly, and the entire line, making a left wheel, came down on his flank, while engaging the Sixth Corps, when he went “whirling up the valley” in confusion. In the pursuit to Fisher’s Hill, the regiment led, and upon its arrival was placed on the skirmish line, where it remained until twelve o’clock noon of the following day. The army was attacked at early dawn…no respite was given to take food until the pursuit was ended.

But once again, the casualties for the 47th were high. Sergeant William Pyers, the C Company man who had so gallantly rescued the flag at Pleasant Hill was cut down and later buried on the battlefield. Corporal Edward Harper of Company D was wounded, but survived, as did Corporal Isaac Baldwin, who had been wounded earlier at Pleasant Hill. Perry County resident and Regimental Chaplain William Rodrock suffered a near miss as a bullet pierced his cap.

Following these major engagements, the 47th was ordered to Camp Russell near Winchester from November through most of December. On 14 November, Second Lieutenant George Stroop was promoted to the rank of captain. Rested and somewhat healed, the 47th was then ordered to outpost and railroad guard duties at Camp Fairview in Charlestown, Virginia (now West Virginia) five days before Christmas.

1865 — 1866

Spectators gather for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, beside the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half-staff after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Assigned next to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Army of the Shenandoah in February, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were soon ordered to move back to the Washington, D.C. area, via Winchester and Kernstown. On 19 April, they were responsible for helping to defend the nation’s capital following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Encamped near Fort Stevens, they received new uniforms and were resupplied with ammunition.

Letters sent to family and friends back home during this time and post-war newspaper interviews with veterans of the regiment indicate that at least one 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train while others may have guarded the key Lincoln assassination conspirators during the early days of their imprisonment and trial, which began on 9 May 1865. During this phase of duty, the regiment was headquartered at Camp Brightwood.

Less than a month after the assassination rocked the nation, Private Daniel S. Zook received word that his fight was over. Per General Orders, No. 53, issued by the U.S. Army’s Middle Military Division Headquarters on 3 May 1865, he was honorably mustered out of service on 17 May 1865.

Return to Civilian Life

Lewistown, Mifflin County, Pennsylvania (circa 1886, Ellis’ History of That Part of the Susquehanna and Juniata Valleys, public domain).

Following his honorable discharge from the military, Daniel Zook returned home to Pennsylvania, where he began a new journey as a family man. In 1867, he wed Mary Elizabeth Howe (1844-1926) and, in fairly short order, welcomed the births of children Ida J. (born circa 1869), Milton O. (1873-1901), and Minnie A. Zook (1874-1961), who was born in Lewistown, Mifflin County on 24 November 1874.

By 1870, he was employed as a house carpenter who resided in Derry Township, Mifflin County with his wife and their daughter Ida. U.S. Civil Service records of the period documented that he also served as a postmaster for the community of Maitland in Derry Township in 1877, for which he was paid a salary of $26.36.

In 1880, after a decade or more of carpentry work under his belt, he continued to reside in Derry Township with his wife and their children, Ida, Milton and Minnie. Also living with them was Daniel Zook’s mother-in-law, Margaret Howe. Still residing in Derry Township in 1890, Daniel Zook was documented that year by the special federal census of Union veterans and widows as a resident of the community of Maitland.

According to History of That Part of the Susquehanna and Juniata Valleys in Pennsylvania, Maitland was “a station on the Mifflin and Centre Railroad, about five miles from Lewistown and Jack’s Creek. In addition to a post office, the town also had a “store, depot, school-house and a few dwellings” in 1886, as well as a grist mill and sawmill, and was also home to the Brethren Church’s Dry Valley branch with its one hundred and five-member congregation. One of its deacons was Daniel Zook.

By 1900, the Zook’s household in Maitland had dwindled to just family patriarch Daniel Zook, his wife, and their daughter, Minnie. Sadly, the journey of his son, Milton, was a short-lived one. Betrothed to Annie Edmiston sometime after the turn of the century, Milton Zook was hit by a train and killed on 3 February 1901. Following funeral services, he was laid to rest at the Maitland Brethren Cemetery in Maitland.

Daniel Zook’s daughter, Minnie, however, had a brighter future ahead of her. Following her post-turn of the century marriage to Jacob D. Ellinger (1875-1931), she welcomed the birth of son Lee O. Ellinger. (1906-1993).

Death and Interment

The old soldier, however, did not live to see the birth of his grandson. Following his death on 8 February 1904, Daniel S. Zook was laid to rest at the Maitland Brethren Cemetery.

Just over two decades later, his widow, Mary E. (Howe) Zook, followed in him in death. After her passing in 1926, she was laid to rest beside him at the Maitland Brethren Cemetery.

Their daughter, Minnie A. (Zook) Ellinger, who had gone on to live a long, full life, ultimately passed away in Lewistown, Mifflin County on 10 August 1961. She, too, was then laid to rest at the same cemetery where her parents had been buried.

Sources:

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1.Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Ellis, Franklin. History of That Part of the Susquehanna and Juniata Valleys, Embraced in the Counties of Mifflin, Juniata, Perry, Union and Snyder, in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, in Two Volumes, vol. I. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Everts, Peck & Richards, 1886.

- Register of Officers and Agents, Civil, Military, and Naval, in the Service of the United States on the Thirtieth of September, 1877, p. 694.Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1878.

- Schmidt, Lewis G. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- U.S. Census and U.S. Census of Veterans and Widows of the Civil War (1890). Washington, D.C.: 1870, 1880, 1890, 1900.

- Zook, Daniel S., in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

You must be logged in to post a comment.