Born in Juniata County, Pennsylvania on 12 July 1836 (alternate birth year: 1840), William J. Smith was destined to have a difficult life. While his formative years remain shrouded in mystery, his record of service to the nation is crystal clear.

He helped to save the United States from disunion, but suffered greatly while doing so.

American Civil War — 126th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry

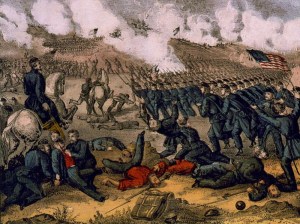

Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia, 12-15 December 1862 (excerpt, Currier & Ives, 1862, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

As America’s Civil War raged on into its second year, William J. Smith realized that he could no longer sit on the sidelines as others from his community and commonwealth were fighting to preserve the Union. So, he enrolled for military service in Mifflintown, Juniata County on 3 August 1862 and then officially mustered in for duty at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania on 9 August as a private with Company F of the 126th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Given basic training in light infantry tactics, they were subsequently transported by rail, on 15 August, to Washington, D.C., where they then were ordered to cross the Potomac River and make camp at Fort Albany. Breaking camp a week later, they and their fellow 126th Pennsylvanians marched to Cloud’s Mills,Virginia and were attached to the brigade of Brigadier-General E. B. Tyler, who ordered that they be given two additional weeks of training. Stationed there until 12 September, they marched toward Meridian Hill. Ordered to march toward Antietam, Maryland on 14 September, they reached the Monocacy on 16 September. Encamped there until mid-afternoon the next day, they finally reached the battlefield at Antietam the next morning and were assigned to the reserve units of the U.S. Army of the Potomac that were led by Porter. As the fighting drew to a close, without their having seen action, they were ordered to make camp at Sharpsburg, Maryland. Stationed there until 30 October, they were then moved to Falmouth, Virginia, where they remained until 19 November. According to historian Samuel P. Bates:

At four o’clock on the morning of the eleventh of December, [the 126th Pennsylvania] moved from camp for its initial battle. For two days it was held in suspense, the music of bands and the heavy booming of Burnside’s cannon filling the air. On the 13th the brigade crossed the Rappahannock, on the upper bridge, and passing up through the town, was led at half-past three out on the Telegraph Road to a low meadow on the right, where it was exposed to a heavy fire of artillery, without shelter and without the ability to offer the least resistance…. After a little delay it was ordered to the left of the road, under cover of a hill. The road was swept by the enemy’s shells, and the bullets of his sharp-shooters….Three fruitless attempts had already been made to carry the frowning heights above and now Humphreys’ Division was ordered up for a final charge…. Forming his brigade in two lines, the One Hundred and Twenty-sixth on the right of the second line, with orders to the men not to fire, but rely solely upon the bayonet, Tyler sounded the charge. Forward went that devoted brigade, uttering heroic cheers, ascending the hill in well ordered lines, and on past the brick house on Marye’s Hill, over the prostrate lines of the last charging column, and up within a moment’s dash of the stone-wall where the enemy lay. But now that fatal wall was one sheet of flame, and to add to the horror of the situation, the troops in the rear opened, every flash in the twilight visible. Bewildered, and for a moment irresolute, the troops commenced firing. This was fatal. The momentum of the charge was lost, and staggering back to the cover of the house, and desending the declivity, re-formed at the foot of the hill. At the head of his men, heroically urging them on at the farthest point in the charge Colonel Elder fell, severely wounded. The loss in that brief charge was twenty-seven killed, fifty wounded, and three missing.

Afterward, Union Major-General Joseph Hooker was reported to have said, “No prettier sight was ever seen than the charge of that division.”

But the Battle of Fredericksburg had proven to be a costly loss for the Union Army. Among those released from service after that engagement was Private William J. Smith, who was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate of disability two days before Christmas (on 23 December 1862) and sent home to Pennsylvania to recover, according to historian Samuel P. Bates.

American Civil War — 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry

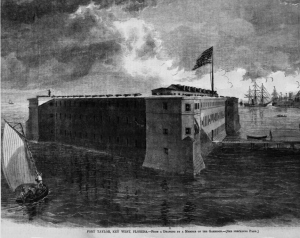

Realizing that America’s terrible civil war was far from over, William J. Smith chose to re-enlist with the Union Army on 27 November 1863. After re-enrolling in Mifflintown, Juniata County, Pennsylvania, he officially re-mustered for duty — but did so this time as a private with Company D of the battle-hardened 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg on 28 November. According to his entry in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives, Private Smith was subsequently transported south by ship to Florida, where he connected with his regiment at Fort Taylor in Key West on 10 October 1863.

Military records at the time described him as being six feet tall with dark hair and blue eyes.

In addition to the strategic role played by the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers in preventing foreign powers from assisting the Confederate Army and Navy in gaining control over federal forts in the Deep South, the regiment he was joining had also been called upon to play an ongoing role in weakening Florida’s abilities to supply and transport food and troops throughout areas held by the Confederate States of America.

Prior to intervention by the Union Army and Navy, the owners of plantations and livestock ranches, as well as the operators of small, family farms across Florida, had been able to consistently furnish beef and pork, fish, fruits, and vegetables to Confederate troops stationed throughout the Deep South during the first year of the American Civil War. Large herds of cattle were raised near Fort Myers, for example, while orchard owners in the Saint John’s River area were actively engaged in cultivating sizeable orange groves (while other types of citrus trees were found growing throughout more rural areas of the state).

Florida was also a major producer of salt, which was used as a preservative for food. As a result, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and other Union troops across Florida were ordered to capture or destroy salt manufacturing facilities in order to further curtail the enemy’s access to food.

1864

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers experienced yet another significant change when members of the regiment were ordered to expand the Union’s reach by sending part of the regiment north to retake possession of Fort Myers, a federal installation that had been abandoned in 1858, following the federal government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. In response, A Company Captain Richard Graeffe and a group of soldiers from Company A traveled north, captured the fort and began conducting cattle raids to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across Florida. They subsequently turned the fort not only into their base of operations, but into a shelter for pro-union supporters, escaped slaves, Confederate deserters, and others fleeing Rebel troops.

Red River Campaign

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had begun preparing for the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer, the Charles Thomas, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by the men from Companies E, F, G, and H.

Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost-fully-reunited regiment moved by train to Brashear City (now Morgan City, Louisiana) before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the U.S. Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps (XIX Corps), and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks. (Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the soldiers from Company A were assigned to detached duty while awaiting transport that enabled them to reconnect with their regiment at Alexandria, Louisiana on 9 April).

From 14-26 March, the 47th passed through New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington while en route to Alexandria and Natchitoches. Often short on food and water, the regiment encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day, marching until mid-afternoon.

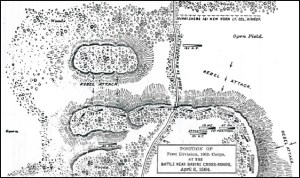

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division, sixty members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were cut down on 8 April during the volley of fire unleashed in the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads. The fighting waned only when darkness fell. Exhausted, those who were uninjured collapsed between the bodies of the gravely wounded and dead. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate Major-General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner and son of Zachary Taylor, former president of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault during what has since become known as the Battle of Pleasant Hill.

The Union Army’s casualties were severe, particularly for Company D of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers. Private Ephraim Clouser, who was listed among the wounded and missing, had been shot in the right knee by a Confederate rifle. He and multiple other 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantrymen, including Private William J. Smith, had been captured by Rebel troops and marched roughly one hundred and twenty-five miles southwest to Camp Ford, the largest Confederate States prison camp west of the Mississippi River.

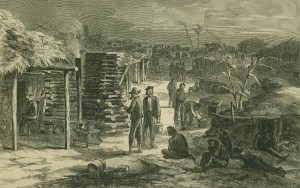

Camp Ford in Texas became the largest Confederate Army prison camp west of the Mississippi River in 1864 (Harper’s Weekly, 4 March 1865, public domain).

Located in Smith County, Texas, near the town of Tyler, that prisoner of war camp has been portrayed by some historians as far less dangerous of a place of captivity for Union soldiers than Andersonville and other Confederate prisons because its living conditions were reportedly “better” than the conditions found at those infamous POW camps — theoretically because the number of POWs held at Camp Ford was smaller and, therefore, “more easily cared for.” But as Camp Ford’s POW population skyrocketed in 1864, fueled by the capture of thousands of Union soldiers during multiple Red River Campaign battles, those living conditions quickly deteriorated.

As food, safe drinking water and adequate shelter became increasingly scarce, more and more of the Union soldiers confined there grew weak from starvation, fell ill and died due to the spread of typhoid and other infectious diseases, as well as the cases of scurvy caused by the lack of fruit and other healthy foods — and by the cases of dysentery and chronic diarrhea caused by the unsanitary placement of outdoor latrines near the camp’s water source.

On 12 June 1864, Private Samuel Kern, a D Company comrade of Privates Clouser and Smith, lost his personal fight to survive. Following his death at Camp Ford, he was buried somewhere on the camp’s grounds. The location of his final resting place is still unknown.

But through it all, Private William J. Smith somehow managed to survive. Finally released during a prisoner exchange on 22 July 1864, he was given medical treatment by Union Army physicians before being allowed to return to duty with his regiment. But he had missed a number of the key engagements that his D Company comrades had endured while he was imprisoned: the Battle of Cane River near Monett’s Ferry, Louisiana (23 April), the construction of Bailey’s Dam on the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana (late April through Mid-May), the Battle of Mansura near Marksville, Louisiana (16 May), a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln (early July), and the Battle of Cool Spring near Snicker’s Gap, Virginia (mid-July).

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Recovered from his experience as a POW, Private William J. Smith was reunited with his 47th Pennsylvania comrades sometime in the late summer or early fall of 1864 — during the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign of legendary Union Major-General Philip H. Sheridan. On 20 August, Henry Wharton of the 47th Pennsylvania’s Company C detailed what had happened to Private Smith and the other Union POWs during their imprisonment at Camp Ford:

While at Tyler, Texas, they were vaccinated or innoculated, with impure matter which impregnated their blood and now they are afflicted with ulcerated limbs and sore eyes. The fiends, pretending to give these men a preventive for small pox, filled their systems with a loathsome disease that will cling to them through life. Is not this an inhuman act? Samuel Miller is in the hospital at New Orleans.

Joseph Shipman, who was serving with Company F of the 19th Iowa Infantry and was also captured on 29 September 1863 and held as a POW by Confederate forces from that time until he was discharged during the same prisoner exchange as Private Smith (22 July 1864), provided further details of life at Camp Ford via a letter to his brother in Sunbury, Pennsylvania, which was penned in New Orleans on 28 July and published on 13 August in the Sunbury American:

MY DEAR BROTHER,

You will have heard by the papers ere this reaches you, of our return and exchange from a ten months captivity in Rebeldom….

We were started on foot for Tyler, Texas, 400 miles distant, which place we reached in 23 days, including delays and stoppages.

I have not time to tell you now of the many abuses and insults that we were compelled to submit to, but I am certain no prisoners ever endured more than we did during the cold weather of last winter.

We were paroled on the 5th inst., left Tyler on the 9th for Shreveport, La., distant 119 miles. We made the trip through in four days, three-fourth of the men were barefooted and so ragged that it was impossible for many of us to conceal our nakedness. We were taken on steamers from Shreveport to the north Red River where we were met by the Commissioner of exchange for this Department with an equal number of Confederate prisoners and the exchange took place on the 22d. We left on the 23d for this Port [New Orleans], arrived here on the 24th, where we are now comfortably quartered with a whole new suit, plenty to eat and drink, all of which we have been strangers to for the last ten months, our food while we were prisoners consisted almost exclusively of corn meal and beef, and very small rations at that.

Fifteen members of the 47th Pennsylvania were inmates of the stockage at Tyler with us for a short time. Some four or five of Captain Gobin’s company [Company C] of Sunbury among them, they came out and were exchanged with us on the 22nd inst., among them was Samuel Miller, an old acquaintance of mine.

Your affectionate brother,

JOSEPH R. SHIPMAN,

Co. F, 19th Iowa

Having been attached to the Middle Military Division, U.S. Army of the Shenandoah beginning in August, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry continued to perform defensive duties in and around Halltown, Virginia during August and early September, while engaging in a series of back-and-forth movements between Halltown, Berryville, Middletown, Charlestown, and Winchester as part of a “mimic war” being waged by the Union forces of Major-General Sheridan with those commanded by Confederate Lieutenant-General Jubal Early.

From 3-4 September, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers took on Early’s Confederates again — this time in the Battle of Berryville. But that month also saw the departure of several 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers who had served honorably, including Company D’s Captain Henry Woodruff, First Lieutenant Samuel Auchmuty, Sergeants Henry Heikel and Alex Wilson, and Corporals Cornelius Stewart and Samuel A. M. Reed — many of whom mustered out on 18 September 1864, upon expiration of their respective service terms.

Those of the 47th who remained were about to engage in their regiment’s greatest moments of valor.

Battles of Opequan and Fisher’s Hill, September 1864

Together with other regiments under the command of Union Major-General Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, commander of the 19th Corps, the members of Company D and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers helped to inflict heavy casualties on Lieutenant-General Early’s Confederate forces at Opequan (also spelled as “Opequon” and referred to as “Third Winchester”). The battle is still considered by many historians to be one of the most important during Sheridan’s 1864 campaign; the Union’s victory here helped to ensure the reelection of President Abraham Lincoln.

The 47th Pennsylvania’s march toward destiny at Opequan began at 2 a.m. on 19 September 1864 as the regiment left camp and joined up with others in the Union’s 19th Corps. After advancing slowly from Berryville toward Winchester, the 19th Corps became bogged down for several hours by the massive movement of Union troops and supply wagons, enabling Early’s men to dig in. After finally reaching the Opequan Creek, Sheridan’s men came face to face with the Confederate Army commanded by Early. The fighting, which began in earnest at noon, was long and brutal. The Union’s left flank (6th Corps) took a beating from Confederate artillery stationed on high ground.

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union Army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces, Battle of Opequan, 19 September 1864 (Kurz & Allison, circa 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania and the 19th Corps were directed by Brigadier-General William Emory to attack and pursue Major-General John B. Gordon’s Confederate forces. Some success was achieved, but casualties mounted as another Confederate artillery group opened fire on Union troops trying to cross a clearing. When a nearly fatal gap began to open between the 6th and 19th Corps, Sheridan sent in units led by Brigadier-Generals Emory Upton and David A. Russell. Russell, hit twice — once in the chest, was mortally wounded. The 47th Pennsylvania opened its lines long enough to enable the Union cavalry under William Woods Averell and the foot soldiers of General George Crook to charge the Confederates’ left flank.

Afterward, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were sent out on skirmishing parties before making camp at Cedar Creek. Moving forward, they would continue to distinguish themselves in battle, but would do so without two more of their respected commanders: Colonel Tilghman Good, founder of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers; and Good’s second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel George Alexander, who mustered out from 23-24 September upon the expiration of their respective terms of service.

Fortunately, they were replaced by others equally admired both for their temperament and their front line experience: Second Lieutenant George Stroop, who was promoted to lead Company D, and John Peter Shindel Gobin, Charles W. Abbott and Levi Stuber, who ultimately became the three most senior leaders of the regiment.

Battle of Cedar Creek, October 1864

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, “Surprise at Cedar Creek,” captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle-pit positions, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

It was during the fall of 1864 that Major-General Philip Sheridan began the first of the Union’s true “scorched earth” campaigns, starving the enemy into submission by destroying Virginia’s crops and farming infrastructure. Viewed through today’s lens of history as inhumane, the strategy claimed many innocents — civilians whose lives were cut short by their inability to find food. This same strategy, however, almost certainly contributed to the further turning of the war’s tide in the Union’s favor during the Battle of Cedar Creek on 19 October 1864. Successful throughout most of their engagement with Union forces at Cedar Creek, Early’s Confederate troops began peeling off in ever growing numbers to forage for food, thus enabling the 47th Pennsylvania and others under Sheridan’s command to rally.

From a military standpoint, it was another impressive, but heartrending day. During the morning of 19 October, Early launched a surprise attack directly on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. Early’s men were able to capture Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles — all while pushing seven Union divisions back. According to Bates:

When the Army of West Virginia, under Crook, was surprised and driven from its works, the Second Brigade, with the Forty-seventh on the right, was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat…. Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions, without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers, as he road rapidly past them – “Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!’”

Sheridan Rallying His Troops, Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

The Union’s counterattack punched Early’s forces into submission, and the men of the 47th were commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas who, in 1892, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked” that day. Bates described the 47th’s actions:

When the final grand charge was made, the regiment moved at nearly right angles with the rebel front. The brigade charged gallantly, and the entire line, making a left wheel, came down on his flank, while engaging the Sixth Corps, when he went “whirling up the valley” in confusion. In the pursuit to Fisher’s Hill, the regiment led, and upon its arrival was placed on the skirmish line, where it remained until twelve o’clock noon of the following day. The army was attacked at early dawn…no respite was given to take food until the pursuit was ended.

Once again, the casualties for the 47th were high. Sergeant William Pyers, the C Company man who had so gallantly rescued the flag at Pleasant Hill was cut down and later buried on the battlefield. Corporal Edward Harper of Company D was wounded, but survived, as did Corporal Isaac Baldwin, who had been wounded earlier at Pleasant Hill. Even Perry County resident and Regimental Chaplain William Rodrock of Perry County suffered a near miss as a bullet pierced his cap.

Following these major engagements, the 47th was ordered to Camp Russell near Winchester from November through most of December. On 14 November, Second Lieutenant George Stroop was promoted to the rank of captain.

Rested and somewhat healed, the 47th was then ordered to outpost and railroad guard duties at Camp Fairview in Charlestown, West Virginia five days before Christmas.

1865 – 1866

Still stationed at Camp Fairview in West Virginia as the New Year of 1865 dawned, members of the regiment continued to patrol and guard key Union railroad lines in the vicinity of Charlestown, while other 47th Pennsylvanians chased down Confederate guerrillas who had made repeated attempts to disrupt railroad operations and kill soldiers from other Union regiments.

Assigned in February 1865 to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers continued to perform their guerrilla-fighting duties until late March, when they were ordered to head back to Washington, D.C., by way of Winchester and Kernstown, Virginia.

Joyous News and Then Tragedy

Spectators gather for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, beside the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half-staff after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

As April 1865 opened, the battles between the Army of the United States and the Confederate States Army intensified, finally reaching the decisive moment when the Confederate troops of General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox on 9 April.

The long war, it seemed, was finally over. Less than a week later, however, the fragile peace was threatened when an assassin’s bullet ended the life of President Abraham Lincoln. Shot while attending an evening performance of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre on 14 April 1865, he had died from his wound at 7:22 a.m. the next morning.

Shocked, and devastated by the news, which was received at their Fort Stevens encampment, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were given little time to mourn their beloved commander-in-chief before they were ordered to grab their weapons and move into the regiment’s assigned position, from which it helped to protect the nation’s capital and thwart any attempt by Confederate soldiers and their sympathizers to re-ignite the flames of civil war that had finally been stamped out.

So key was their assignment that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were not even allowed to march in the funeral procession of their slain leader. Instead, they took part in a memorial service with other members of their brigade that was officiated by the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental chaplain, the Reverend William D. C. Rodrock.

Present-day researchers who study letters sent by 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers to family and friends back home in Pennsylvania during this period, or post-war interviews conducted by newspaper reporters with veterans of the regiment in later years, will learn that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were collectively heartbroken by Lincoln’s death and deeply angry at those whose actions had culminated in his murder. Researchers will also learn that at least one member of the regiment, C Company Drummer Samuel Hunter Pyers, was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train, while other members of the regiment were assigned to guard duty at the prison where the key assassination conspirators were being held during the early days of their imprisonment and trial, which began on 9 May 1865. The regiment was headquartered at Camp Brightwood during this period.

Attached to Dwight’s Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were permitted to march in the Union’s Grand Review of the National Armies, which took place in Washington, D.C. on 23 May.

Reconstruction

War-damaged houses in Savannah, Georgia, 1865 (Sam Cooley, U.S. Army, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Afterward, Private William J. Smith and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians were ordered to America’s Deep South. Stationed in Savannah, Georgia in early June, they were assigned again to Dwight’s Division, but this time, they were attached to the 3rd Brigade, U.S. Department of the South.

Subsequently ordered to relieve the 165th New York Volunteers in Charleston, South Carolina in July 1865, they were quartered in the former mansion of the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury.

Beginning on Christmas day of that same year, the majority of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantrymen, including Private William J. Smith, began to honorably muster out in Charleston — a process which continued through early January 1866.

Following a stormy voyage home, the 47th Pennsylvanians disembarked in New York City and were then transported to Philadelphia by train where, at Camp Cadwalader on 9 January 1866, they were officially given their honorable discharge papers.

Return to Civilian Life

Even in the early 1900s, Duncannon, Pennsylvania retained its rural character (view from Orchard Hill, public domain).

Following his honorable discharge from the military, William J. Smith returned home to Pennsylvania, where he wed Harriet N. Bryner (1842-1890). Together, they welcomed the birth of daughter Mary Elizabeth Smith (1877-1941), who was born in Perry County on 8 May 1877 and would later go on to marry Solomon Tate Sidle (1866-1945). A son, David S. Smith, was then born sometime afterward, according to U.S. Civil War Pension records.

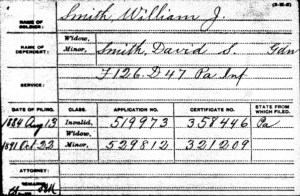

Those same records indicate that William J. Smith was in increasingly poor health as the 1870s passed and the 1880s wore on. As a result, he was compelled by his deteriorating physical condition to apply for a U.S. Civil War Pension on 13 August 1884. Classified as a veteran who was an invalid, he was subsequently awarded financial support by the U.S. Pension Bureau. A resident of Duncannon, Perry County, Pennsylvania, William J. Smith was reported on the 1890 U.S. Veterans’ Schedule as suffering from scurvy.

Preceded in death by his wife, who passed away on 2 March 1890, William J. Smith suffered a grievous work-related accident just over a year later when “one of his hands” was “sawed at the stave mill” in Duncannon on 1 May 1891. According to the Perry County Democrat:

William J. Smith, of Duncannon, met with a serious accident, while working at the stave mill, in that place, the other day. He was sawing blocks with a circular saw, when one of his hands came in contact with the steel teeth and was nearly cut off just above the knuckle joints. Dr. T. L. Johnston dressed the wound. Mr. Smith will probably lose the use of the hand.

Tetanus-Related Death

Sadly, the outcome for William J. Smith was far worse than what his local newspaper had predicted. Despite having received medical treatment for his injury, he subsequently contracted tetanus during the last week of May 1891, which ultimately resulted in his death due to lock-jaw at a hospital in Harrisburg on 3 June. Following funeral services, he was interred at the Union Cemetery in Duncannon, Perry County.

What Happened to His Children?

Wiliam J. Smith and his son, David S. Smith, U.S. Civil War Pension applications, 1884-1891 (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

On 22 October 1891, a court-appointed guardian filed application paperwork for U.S. Civil War Pension support for David S. Smith, the only one of William J. Smith’s children who was still eligible for such support because he was still under the age of sixteen. That support was ultimately granted to David Smith by the U.S. Pension Bureau. Researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story are still searching for additional information about David’s life.

Following her marriage to Solomon T. Sidle in 1896, William J. Smith’s daughter, Mary Elizabeth (Smith) Sidle, welcomed the births of: Anna M. Sidle (1897-1905), who was born on 7 July 1897, but died at the age of eight on 6 September 1905; John Tate Sidle (1909-1985), who was born in Harrisburg on 15 May 1909 and later married Clara Elizabeth Williams (1911-1994) in 1930, before divorcing her and marrying Helen Marie Eckels (1915-2009) in 1960; and Donald Smith Sidle (1917-2000), who was born in Bowmansdale, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania on 12 January 1917 and later wed Miriam L. Lefever (1914-2008).

Ailing with heart disease during her final months, Mary Elizabeth (Smith) Sidle died at the age of sixty-four at her home in Upper Allen Township, Cumberland County, on 2 November 1941, and was buried at the Andersontown Church of God Cemetery in Andersontown, York County, Pennsylvania.

* Researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story are continuing the search for more details about the lives of William J. Smith and his son, David, and hope to purchase copies of his U.S. Civil War military and pension files from the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, which will likely provide crucial details about their respective formative years. You can help support this research in two ways:

1.) If you are a descendant of William J. Smith and/or his son, David S. Smith, please emailing our managing editor to share any details about your ancestor(s); and/or

2.) Support our research by making a donation to this project, using our website’s secure donations page.

Sources:

- “126th Regiment, Pennsylvania Infantry,” in “The Civil War: Battle Unit Details.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Park Service, retrieved online 17 June 2025.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, volumes 1 and 4. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869 and 1870.

- Civil War Muster Rolls (Company F, 126th Pennsylvania Infantry and Company D, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 (Company F, 126th Pennsylvania Infantry and Company D, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- “Florida’s Role in the Civil War,” in Florida Memory. Tallahassee, Florida: State Archives of Florida.

- Hain, Harry Harrison. History of Perry County, Pennsylvania. Including Descriptions of Indians and Pioneer Life from the Time of Earliest Settlement. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Hain-Moore Company, 1922.

- “Mrs. Solomon T. Sidle” (obituary of William J. Smith’s daughter, Mary Elizabeth). York, Pennsylvania: The Gazette and Daily, 3 November 1941.

- “Painfully Injured.” Duncannon, Pennsylvania: The Duncannon Record, 8 May 1891.

- “Roster of the 47th P. V. Inf.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 26 October 1930.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- Smith, William J., in Camp Ford Prison Records (1864). Tyler, Texas: Smith County Historical Society.

- Smith, William J. and David S., in U.S. Civil War Pension General Index Cards (veteran’s application no.: 519973, certificate no.: 358446, filed by the veteran from Pennsylvania, 13 August 1884; application no.: 529812, certificate no.: 321209, filed from Pennsylvania by a guardian on behalf of David S. Smith, the veteran’s surviving minor child, 22 October 1891). Washington D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “The History of the Forty-Seventh Regt. P. V.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Lehigh Register, 20 July 1870.

- William J. Smith (report of William J. Smith’s work-related injury), in “Personal Mention.” New Bloomfield, Pennsylvania: Perry County Democrat, 13 May 1891.

- William J. Smith (report of William J. Smith’s work-related injury which resulted in lock-jaw from tetanus), in “Announcements.” New Bloomfield, Pennsylvania: Perry County Democrat, 27 May 1891.

- William J. Smith, in U.S. Census (“Special Schedule: Surviving Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, and Widows, Etc.”, Duncannon, Perry County, Pennsylvania, 1890). Washington D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Wm. J. Smith,” in “In Memorium.” Duncannon, Pennsylvania: The Duncannon Record, 5 June 1891.

You must be logged in to post a comment.