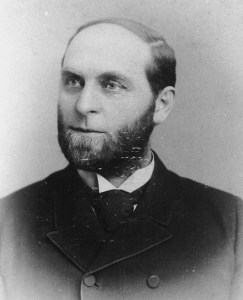

The Reverend Joseph Benson Shaver, shown here circa the 1890s, was a veteran of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (public domain).

Among the most memorable speeches ever given by the Reverend Joseph Benson Shaver, a veteran of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry who had been seriously wounded in the arm during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on 9 April 1864, was an address that he delivered in the city of Hazleton in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania on 30 May 1889 — Decoration Day (now known as Memorial Day). The full text of his speech was published in The Hazleton Sentinel that same day:

Memorial Oration

Mr. Chairman Ladies and Gentlemen, Comrades and Patriots: —

I do not speak to you to-day as a minister of the gospel of Jesus Christ, though I do not forget that such I am, nor yet as a citizen of this grand old commonwealth. Though I rejoice, yea and will rejoice that I was born on her loyal soil. It was this boast that I am a Pennsylvanian, I am a North Carolinian, I am an Ohioan, I am a Georgian, that gave fuel to that dangerous doctrine of States Rights which entered so largely into the attempted dismemberment of our Federal Union. I come to speak to you as an American citizen.

More than two centuries ago there alighted upon these shores a strange spirit, comparatively friendless and fugitive. It had the appearance of a pilgrim; bleeding from wounds indicative of the storm and battle strife of the Old World, from which it had fled, yet with the keys of the world’s destiny at its girdle. It was however a generous spirit, friendly to all the vital interests of humanity. Endowed with ubiquity it diffused itself universally.

Standing on the virge of this new civilization by one stroke of its giant arm it severed all false relations, and laid the foundation of an independent government.

From the day when Moses and Aaron, plead in the presence of the tyrant Pharaoh, to the days when Leonidas with his three hundred Spartans stood in the pass of Thermopylae, on to the days when Patrick Henry burst the grave of freedom with his utterances of fire, and on to the days when Abraham Lincoln by one stroke of his pen broke the fetters of enchained millions, the struggles and triumphs of this spirit have been the burden of the world’s history, and inspiration of its song. This is the spirit of liberty. But in this practical world a spirit cannot reach its highest usefulness unless embodied. It was therefore the work of the American Congress to embody this spirit in the Constitution; and I remind you that the document eminating from that body is the most marvelous document on the subject of human rights known to the race outside of the Bible. And rightly did the great English Statesman declare it to be “The most wonderful work ever struck off at a given time by the brain and purpose of man.” Not only must this spirit be embodied, but embodied, it must be protected. To meditate the destruction of a government founded upon such a constitution, was an awful prostitution of the human intellect, to engage in it was an arrangement of the doctrine of peace and good will, which the heavenly visitants inaugurated on the plains of Judea. To succeed in it was to eclipse the sun of our political firmament and entomb the inspiring and redeeming forces of liberty in a long night of disheartening darkness.

This marks a point for my departure. I need scarcely ask why we are here to-day, not simply because of an order from the department of the Grand Army of the Republic, but the day on which the great army of the living are to meet on the silent camping ground of the departed and do honor to the patriotic dead. Although they sleep their last sleep, have fought their last fight and shall no more respond to the call of patriotism, they are not dead. There is no death. They live in their deeds of valor, in their country’s love, in the arts and sciences and in the institutions they aided in founding and perpetuating. The Revolutionary Fathers live in the lessons taught and the scenes enacted at Bunker Hill, at Saratoga, at Valley Forge, and at Yorktown. The soldiers of 1812 live in the battles of Chippewa, Lundy’s Lane, Queenstown and New Orleans; the men whose strong arms and brave hearts carried the stars and stripes across the Republic of Mexico, made a record which is indelibly written on the walls of Monterey, the plains of Buena Vista, and the burning sands of Veracruz. But there are lessons which are nearer to us, scenes that touch us with deeper personal interest, lessons which we gather [illegible 5-6 words] fathers and brothers, in the putting down of the great rebellion. Lessons which come to us from the battlefields of Appomattox, and Gettysburg, of Murfreesboro and Chickamauga, of Shiloh and Vicksburg, of Fort Wagner and Fort Donnelson, of Fisher’s Hill and Antietam and hundreds of other fields. What a host of brave spirits ascended from these fields of carnage, and constitute that cloud of patriotic witnesses, who watch with deepest solicitude their comrades who are alive doing their part in carrying forward the highest interests of this great Republic.

And fellow soldiers alive and here it is no fault of ours, that we are here to-day to do honor to these heroic dead. It is in the Providence of God that we are alive. We bared our breasts to the same storm of shot and shell which swept our comrades down. I remember with sad distinctness when he who had marched side by side with me, for more than eighteen months, fell on my right, and my own arm dropped by my side like a lump of lead because there was lead in it. To tell the charming story of the past of this Republic, would require the longest hour of time and the brightest genius of our land. Every Republic seems to have its prominent and well defined trial periods, or ordeals through which it passes to reach its desired haven of rest. It must demonstrate its ability to throw off its dependence, and establish its independence of the Government to which it was subject. It must prove its ability to repel invasion on its own soil. It must be able to command the observance of the laws of Nations, and sustain National honor abroad. It must establish its ability to put down insurrection and rebellion at home. Through all these critical periods, this Republic has triumphantly passed under the leadership of American Patriotism. My fellow citizens, the truths, the principles that our National sacrifices and sufferings have confirmed and sealed, must be cherished and perpetuated, if our Nation, which would have its character and the character of its individual citizens formed and molded by the great, manly and patriotic truths, which the calmest judgment, the best attested history and the highest patriotism vindicate, confirm and establish.

About the year 1860 this government reached a period when questions of almost infinite importance demanded an answer and settlement. Questions such as these, Is patriotism a mere parade day sentiment, or something stronger and more precious than trade or treasure? Is personal freedom, crowned and sceptered manhood, a mere rhetorical flourish, or is it prized above wealth and life? Is this American Federal sovereignty, a magnificent Nation or merely a confederation of discordant petty sovereignties? Who is kingly enough to hold the helm of state and navigate the seething waters until the solution is reached? It must be held heroically, firmly in the face of death and steered to land. Out on one of the great lakes, a few years since, a vessel took fire some distance from the shore. Terror and dismay spread fore and aft, over cabin and deck. The Captain through his trumpet called aloud, “John Maynard, are you at the helm? “Aye, aye.” “What is her course?” “Due West, sir.” “Turn her Southwest and run her on shore.” The devouring flames have crowded the affrighted passengers on the foredeck, and are wreathing their red lips about the pilot house. Again the Captain cries aloud through his trumpet, “John Maynard!” “Aye, Aye, sir.” “Can you hold on four minutes longer?” “By God’s help I’ll try, sir.” The flames are singeing the gray hairs about his temples, the hand on the helm is frying in the heat, but the vessel has struck the shore, and every passenger with a prayer of thanksgiving is on the land, but old John Maynard drops in the burning ruins of the pilot house a martyr. The people called Abraham Lincoln from his prairie home, gave him the helm, bade him turn the burning ship due North, and run her ashore. For four years he stood in the pilot house guiding the vessel. Some of the passengers laughed at the big hand on the helm, others jeered at his ungainly figure and queer postures, others cursed him for a buffoon, a tyrant and a traitor, but millions saw kindness, firmness and fearlessness in his big homely face, and patriotism shining in his pensive tearful eyes.

And they said, “Abraham Lincoln, will you serve us four years more?” “By God’s help I’ll try.” “Then hold on four years longer.” And with his knee upon the stanchion, and his face beaming with hope, he kept his hand upon the helm until by a traitor’s hand it was blown from his grasp; but the ship was in the harbor and the passengers safely on the shore of Liberty and Peace; but Abraham Lincoln lay dead in the pilot house a martyr.

But American patriotism and heroism not only wanted a ruler. It was a battle hour and the nation wanted a warrior-like leader. Then, like the Prophet Samuel with Jesse’s sons, she calls one after another to pass before her on trial, Eliad, and Abinadab and Shamiah, and so on until the seven sons come, but David, the one to annoint is not there. But there is a man who has been living among the people of Illinois, where you got your pilot. He has been playing for a while along the banks of the Mississippi and its tributaries, and his name is U. S. Grant. Send and fetch him. He was brought and proved the chosen one. He was annointed with the oil of victory, and was such a ruthless “butcher” that he butchered the strongest rebellion’s bull ever pushed against any Government on earth. Cool, modest, taciturn, strategic, self-reliant and unyielding, he out-generaled every captain on field of battle, and proved himself fit to be a lieutenant general and peer of his rank on earth. And Sherman, Thomas, Hancock, Sheridan, Meade, Logan and many others, who have shown themselves worthy majors of the mightiest chieftain of modern times. Then there were the men, who came by thousands to the rescue, willing victims for the altar of Liberty. Not men driven by transient, fiery impulse or ambition, but men, who calmly made their wills and turned to the gory fields of death; dauntless, daring men who said, “The hand that dare despoil the citadel of freedom strike it with the sword from the shoulder blade.” They came from Maine to California. State after State wheeled into battle line, their provincial flags floating beneath the National banner. These are the men who claim our meed of honor. These are the men whose names shall always hold their places like stars that gem the azure sky; whose deeds on history’s pages enrolled, are sealed as an everlasting treasure. What could the mightiest chieftain have done without them? They are the National epistles of American heroism read and known to all men. Let us pause just for a moment in the midst of what they have done and won for us. The first act of heroism with many was leaving home. See that soldier parting with his loved ones; he leaves the home of his childhood, a mother’s love, a sister’s kindness and a brother’s companionship. But this is not all, there are little cherubs, children that call them papa, and one fond loving woman who calls him husband. Kiss them passionately, heroic man, you will see them no more for three long years, perhaps forever; brave heart, be strong; don’t break here, kiss them again and then away. Oh, this is the first set in the drama of crucifixion; this is the Gethsemena agony that prepares for the cross; this is the heroism of the American volunteer for Liberty and Country. Before them are the battlefields “with garments rolled in blood,” and the prison pen of torture. The field of conflict was nearly two thousand miles from east to west and north to south. Over this vast continent of battle they marched and marched and countermarched; advancing on one line; driven back upon another, overpowered, but never conquered; sometimes betrayed but never betraying, they pushed a brave heroic stubborn foe from trench to trench, from fortress to fortress, plucking the flag of treason from exulting foes. With their tramp, tramp, tramp, they trampled the heart of the confederacy, going with Sherman to the sea, they left the Tennessee river behind them, and for three hundred miles through Georgia mountains drove the enemy from one gorge to another, and from one mountain fastness to another, “going with Sherman to the sea.” Their manly footfalls shook the continent. The dying prisoners at Andersonville heard the march and began to sing:

“Tramp, tramp, tramp the boys are marching

Cheer up, comrades, they will come;

And beneath the starry flag, we shall breathe the air again,

In the free land of our own loved home.”

Through the Chicahominy and the bloody wilderness, these brave men march. Start from Washington, go down the Potomac and up the Rappahannock; pass from one side of red Virginia to another; then travel a thousand leagues along the seashore around the banks of the gulf, up the Mississippi and the Missouri; up the Arkansas and the Red river, along the Tennessee and Cumberland, through mountain passes over rocky heights, and up the Ohio and all along are grassy mounds which mark a soldier’s grave. They rest altogether irrespective of political party preference or ecclesiastical faith. Democrat and Republican, the white and black man, the Protestant, the Catholic, all slumber together. But American patriotism had its severest test in hospital and prison. It was in the latter that the bread of treason was offered to starving men, in barter for surrender of patriotism. Do they yield these men too feeble to stand, sitting out there on the verge of starvation, so thin, so emaciated, with lips so parched that they crack when they move and joints so dry that you would not be surprised to see them snap like a pipe stem? And we wonder is there enough of the blood and patriotism of their forefathers left to keep them in this hour. Thank God there was. No tongue can utter the heroism of patriotism, endured in ths Southern prisons. That banner was the prisoner’s idol, his country was his sweetheart, and at her feet he laid all the jewels of his patriotic manhood, and went home to the warrior’s rest. These deeds are the “Jewels that on the stretched forefinger of time, sparkle forever.”

We have heard, but in a low whisper what American patriotism suffered; its true sound is as the mighty thunder and the noise of many waters. Let me point out in rapid succession a few things it has won for us. It has won for us a strong genuine nationality of sentiment and glory that will bind our country together, as with bands of iron. Before we were provincial and sectional, while the English, the Swede, the German, the French and almost every other country had a nationality. But we will lack this no longer. We have enacted mightier deeds in our land, crowded more illustrious names into our annals, and achieved grander things in a few years than mark the histories of monarchies or empires for a thousand. We have rebaptised by immersion in blood and given our nation a new name of freedom and glory which England will envy, France covet, and Russia and Germany honor. Men are to-day proud to say I am an American citizen. Gettysburg and Atlanta are united by ties stronger than iron rails and more enduring. In the next place our Starry banner has been washed in blood and made clean. Thirty years ago one of our sweetest immortal bards wrote these lines on our flag:

“Wherever now to sun and breeze,

My country is thy flag unrolled;

With scorn the gazing stranger sees

A stain on every fold.”

Many were very angry at the author for writing such truth, others blushed for very shame; but listen how the same poet sings since you came marching home:

“But now I see it, in yonder sun

A free flag floats from yonder dome

And at the Nation’s heart and home,

The justice long delayed is done.Wherever now the sun and breeze,

My country is thy flag unrolled;

With joy the gazing stranger sees

No stain on any fold.

Heroes’ hands have washed them clean.”

Again you have freed the pulpit and the press and the politicians of the North of moral cowardice. There is now an independence and fearlessness in all these never seen before you came marching home. You have emancipated tongue and pen, and press and pulpit. Before closing I would like to ask a question and if you please, answer it in my own way. What is the meaning of strewing flowers on soldiers’ graves? Is it simply to crown personal worth, sacrifice and heroic endurance and bravery? If so you should heap high the fragrant blossoms on the graves of the patriot mothers and sisters of this land, who ever stood in the forefront to do honor to their Country’s flag and the Country’s patriots. If so then I had friends who fought on the rebel side, the equal of any who fell on the union side. On the other side were as gallant, as heroic soldiers, men of as honest convictions and of as much personal worth, as are to be found anywhere in the land. But we are not honoring simply honest convictions, heroic bravery and personal excellence. The flowers are to garland the bravery, the heroism, and the sufferings, endured for the truth, for the principles of nationality, unity, law, righteousness and liberty. For the sake of posterity, these distinctions ought to be kept clear and well defined. And this flowery ceremony ought to mark this distinction, and must or it cannot be justified or continued. These fragrant crowns are for the heroes and soldiers of the union, law, and freedom.

“Go lightly press the hallowed ground,

Where our martyred heroes sleep,

Bow down the head, with grief profound,

And o’er their smouldering ashes weep.

That our loved country might be free,

They died — they died for you and me.Above them bid the old flag wave,

The dear old flag they loved so well,

The ensign which they died to save,

Dear Freedom’s starry sentinel,

Flag which the Nations joyed to see,

They died to save to you and me.Go — Take from Flora’s fragrant bowers.

These choicest of the gems of spring,

O’er their graves in rosy showers,

Scatter them, and sweetly sing,

For celestial Liberty

They died — they died for you and me.”

Let us bring flowers; bring the floral cross, and let it symbolize their sacrifice; bring the ivy leaf and let it serve as a crown of honor to them; bring flowers of every hue, the red a token of their poured out blood. The white emblematic of the purity of their patriotism, the blue symbolizing their devotion. Bring the red, white, the blue constituting the immortal colors of the old flag they loved so well.

“Cover them over with beautiful flowers

Deck them with garlands these heroes of ours.”

Departed heroes accept these modest offerings and as breezes steal away their perfume and scatter it from noiseless wings to sweeten earth, so may the fragrance of your immortal deeds, regale our spirits, and bring us into an appreciation of the truth that in all life’s relations, whether of peace or war, subordination to duty is exaltation of self.

Living comrades and patriots and fellow citizens may God bless you, and make you heirs of even a better land than this, that is an heavenly [one].

Sources:

- Blight, David W. The First Decoration Day. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University, 27 April 2015.

- “Death of Rev. J. B. Shaver: Well Known Member of Central Pennsylvania Methodist Conference.” Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: Wilkes-Barre Semi-Weekly Record, 20 November 1903.

- “In Memory of Dr. Shaver” (recounting of the commentary made about the Reverend Doctor Joseph Benson Shaver during his memorial service at St. Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Hazleton, Pennsylvania). Danville, Pennsylvania: Montour American, 26 November 1903.

- “Rev. J. B. Shaver Dead: By Associated Press to the Patriot.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Patriot, 18 November 1903.

- Shaver, Rev. Joseph B. “Memorial Oration,” in “Our Departed Heroes.” Hazleton, Pennsylvania: The Hazleton Sentinel, 30 May 1889.

- “The 47th P. V. in Action” (casualty report for the 1864 Red River Campaign Battles of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield and Pleasant Hill, Louisiana, 8-9 April 1864). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Patriot and Union, 29 April 1864.

You must be logged in to post a comment.