The Reverend Joseph Benson Shaver, shown here circa the 1890s, was a veteran of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (public domain).

“Mr. Shaver served three years in the Civil War, and wore the button of the G. A. R. He carried the scars of the wounds received in that sanguinary conflict, and was highly esteemed by his fellow soldiers. He has filled some of the most important pastoral charges of his conference…. He was a popular, efficient and faithful man in all the relations of life.” — The Patriot, 23 November 1903

“Rev. J. B. Shaver is a man whose death will be mourned wherever he was known. He was a person of most pleasing personality, kindness and generosity being the ruling traits of his character. As a preacher he was eloquent; his sermons were sound in doctrine and characterized by a breadth of view which stamped him as a conscientious and progressive clergyman. He ranked with the first pulpit orators of the Central Pennsylvania Conference.” — Montour American, 19 November 1903

Formative Years

Born in the Bixler Hills area of Madison Township in Perry County, Pennsylvania on 3 December 1844, Joseph Benson Shaver was a son of the Reverend David Elliott Shaver (1804-1862), a native of Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania, and Perry County native Nancy Elizabeth (Linn) Shaver (1818-1897).

In 1850, he resided with his parents on the Madison Township farm of his maternal grandfather, John Linn. Also living with them were Joseph’s Perry County-born siblings: John Lynn Shaver (1843-1922), who was born in Center Township, Perry County on 16 April 1843 and went on to serve in the Army of the United States Signal Corps during the American Civil War, before marrying Anna L. Davis (1853-1928) and settling with her in Altoona, Blair County, Pennsylvania, where he was employed by the Pennsylvania Railroad Company (P.R.R.); Samuel Cass Shaver (1848-1923), who was born on 13 March 1848 and also later worked for the Pennsylvania Railroad Company; Susan Bowe (aged twenty-three); and David S. Kisler (aged twelve).

Three more younger siblings soon followed: Catharine J. Shaver, who was born circa 1851; Albert Craig Shaver (1855-1927), who was born on 26 January 1855, grew up to become a blacksmith and later wed Anna Mary Bentzel (1859-1911); and David N. Shaver, who was born circa 1858.

No longer residing with his maternal grandfather in 1860, Joseph B. Shaver still lived with his parents and siblings in Madison Township. During the fateful summer of 1861, Joseph Shaver was documented in records of the time as a seventeen-year-old farmer residing in Madisonville, Perry County.

American Civil War

On 9 August 1862, at the age of eighteen, Joseph Benson Shaver enrolled for American Civil War military service in Elliottsburg, Perry County. Less than a week later, he mustered at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County, on 15 August, as a private with Company D of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Transported south by ship to South Carolina, he connected with his regiment from a recruiting depot on 13 September 1862.

* Note: At least one post-war news report stated that Joseph Benson Shaver enlisted at the age of sixteen and not eighteen, as his military records noted.

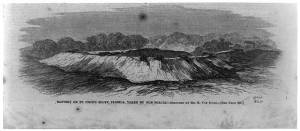

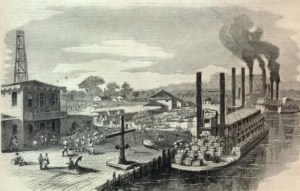

Capture of Saint John’s Bluff, Florida and a Confederate Steamer

Earthworks surrounding the Confederate battery atop Saint John’s Bluff along the Saint John’s River in Florida (J. H. Schell, 1862, public domain).

During an expedition to Florida, which began on 30 September, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined with the 1st Connecticut Battery, 7th Connecticut Infantry and part of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry in assaulting Confederate forces at their heavily protected camp at Saint John’s Bluff, overlooking the Saint John’s River. Trekking through roughly twenty-five miles of swampland and forests, after disembarking from their Union troop transports at Mayport Mills on 1 October, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers captured artillery and ammunition stores (on 3 October) that had been abandoned during the Union Navy’s bombardment of the bluff.

Men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies E and K were then led by Captain Charles H. Yard on a special mission; initially joining with other Union troops in the reconnaissance and capture of Jacksonville, Florida, they were subsequently ordered to sail up the Saint John’s River to seek out and capture any Confederate ships they found. Departing aboard the Darlington, a former Confederate steamer, with protection by the Union gunboat Hale, they traveled two hundred miles upriver, captured the Governor Milton, a Confederate steamer that was docked near Hawkinsville, and returned back down the river with both Union ships and their new Confederate prize without incident. (That Rebel steamer had been engaged in ferrying Confederate troops and supplies around the region.)

Integration of the Regiment

Meanwhile, back at its South Carolina base of operations, the 47th Pennsylvania was making history as it became an integrated regiment. On 5 and 15 October, the regiment added to its rosters several young Black men who had escaped or been freed from plantation enslavement near Beaufort and other areas of South Carolina, including Bristor Gethers, Abraham Jassum and Edward Jassum.

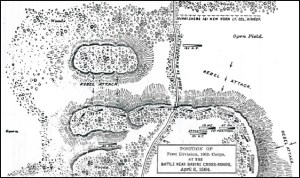

Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina

Highlighted version of the U.S. Army map of the Coosawhatchie-Pocotaligo Expedition, 22 October 1862 (public domain).

From 21-23 October 1862, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers joined with other Union troops in engaging heavily protected Confederate troops in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina, including at Frampton’s Plantation and the Pocotaligo Bridge, a key piece of Deep South infrastructure that senior Union military leaders felt should be eliminated.

Harried by snipers while en route to destroy the bridge, they met resistance from an entrenched, heavily fortified Confederate battery that opened fire on the Union troops as they entered an open cotton field.

Those headed toward higher ground at the Frampton Plantation fared no better as they encountered artillery and infantry fire from the surrounding forests. But the Union soldiers would not give in. Grappling with the Confederates where they found them, they pursued the Rebels for four miles as the Confederate Army retreated to the bridge. Once there, the 47th Pennsylvania relieved the 7th Connecticut.

Unfortunately, the enemy was just too well armed. After two hours of intense fighting in an attempt to take the ravine and bridge, the 47th Pennsylvanians were forced by depleted ammunition to withdraw to Mackay’s Point.

Losses for the 47th were significant. Two officers and eighteen enlisted men died; two officers and an additional one hundred and fourteen enlisted men were wounded.

Badly battered when they returned to Hilton Head on 23 October, a number of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were subsequently selected to serve as the funeral honor guard for General Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel, the commander of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps and Department of the South who had succumbed to yellow fever on 30 October. The Mountains of Mitchel, a part of Mars’ South Pole discovered by Mitchel in 1846 while working as a University of Cincinnati astronomer, and Mitchelville, the first Freedmen’s town created after the Civil War, were both later named for him. Men from the 47th Pennsylvania were given the honor of firing the salute over his grave.

Fort Jefferson and its wharf areas, Dry Tortugas, Florida (Harper’s Weekly, 23 February 1861, public domain).

Having been ordered to Key West, Florida on 15 November 1862 (a return trip for the majority of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers), Private Joseph Benson Shaver and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians would spend much of 1863 guarding federal installations in that state as members of the Army of the United States’ 10th Corps, Department of the South. Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I would garrison Fort Taylor in Key West, while the men of Companies D, F, H, and K would garrison Fort Jefferson, the Union’s remote outpost in the Dry Tortugas off the southern coast of Florida.

After packing their belongings at their Beaufort, South Carolina encampment and loading their equipment onto the U.S. Steamer Cosmopolitan, the officers and enlisted members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry sailed toward the mouth of the Broad River on 15 December 1862, and anchored briefly at Port Royal Harbor in order to allow the regiment’s medical director, Elisha W. Baily, M.D., and members of the regiment who had recuperated enough from their Pocotaligo-related battle injuries at the Union’s general hospital at Hilton Head, to rejoin the regiment.

At 5 p.m. that same evening, the regiment sailed for Florida, during what was described by several members of the regiment as a treacherous and nerve-wracking voyage. According to Schmidt, the ship’s captain “steered a course along the coast of Florida for most of the voyage,” which made the voyage more precarious “because of all the reefs.” On 16 December, “the second night, the ship was jarred as it ran aground on one during a storm, but broke free, and finally steered a course further from shore, out in the Gulf Stream.”

In a letter penned to the Sunbury American on 21 December, Musician Henry Wharton provided the following details about the regiment’s trip:

On the passage down, we ran along almost the whole coast of Florida. Rather all dangerous ground, and the reefs are no playthings. We we jarred considerably by running on one, and not liking the sensation our course was altered for the Gulf Stream. We had heavy sea all the time. I had often heard of ‘waves as big as a house,’ and thought it was a sailors yarn, but I have seen ’em and am perfectly satisfied; so now, not having a nautical turn of mind, I prefer our movements being done on terra firma, and leave old neptune to those who have more desire for his better acquaintance. A nearer chance of a shipwreck never took place than ours, and it was only through Providence that we were saved. The Cosmopolitan is a good riverboat, but to send her to sea, loadened [sic, loaded] with U.S. troops is a shame, and looks as though those in authority wish to get clear of soldiers in another way than that of battle. There was some sea sickness on our passage; several of the boys ‘casting up their accounts’ on the wrong side of the ledger.

According to Corporal George Nichols of Company E, “When we got to Key West the Steamer had Six foot of water in her hole [sic, hold]. Waves Mountain High and nothing but an old river Steamer. With Eleven hundred Men on I looked for her to go to the Bottom Every Minute.”

Although the Cosmopolitan arrived at the Key West Harbor on Thursday, 18 December, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers did not set foot on Florida soil until noon the next day. The men from Companies C and I were immediately marched to Fort Taylor, where they were placed under the command of Major William Gausler, the regiment’s third-in-command. The men from Companies B and E were assigned to the older barracks that had been erected by the United States Army, and were placed under the command of B Company Captain Emanuel P. Rhoads, while the men from Companies A and G were placed under the command of A Company Captain Richard Graeffe, and stationed at newer facilities known as the “Lighthouse Barracks,” which were located on “Lighthouse Key.”

On Saturday, 21 December, Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, the regiment’s second-in-command, sailed away aboard the Cosmopolitan with the men from Companies D, F, H, and K, and headed south to Fort Jefferson, roughly seventy miles off the coast of Florida (in the Gulf of Mexico) to assume garrison duties there. According to Musician Henry Wharton:

We landed here [Fort Taylor] on last Thursday at noon, and immediately marched to quarters. Company I. and C., in Fort Taylor, Company E. and B. in the old Barracks, and A. and G. in the new Barracks. Lieut. Col. Alexander, with the other four companies proceeded to Tortugas, Col. Good having command of all the forces in and around Key West. Our regiment relieved the 90th Regiment N. Y. S. Vols. Col. Joseph Morgan, who will proceed to Hilton Head to report to the General commanding. His actions have been severely criticized by the people, but, as it is in bad taste to say anything against ones [sic, one’s] superiors, I merely mention, judging from the expression of the citizens, they were very glad of the return of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers….

Key West has improved very little since we left last June, but there is one improvement for which the 90th New York deserve a great deal of praise, and that is the beautifying of the ‘home’ of dec’d soldiers. A neat and strong wall of stone encloses the yard, the ground is laid off in squares, all the graves are flat and are nicely put in proper shape by boards eight or ten inches high on the end sides, covered with white sand, while a head and foot board, with the full name, company and regiment, marks the last resting place of the patriot who sacrificed himself for his country….

1863

Fort Jefferson’s moat and wall, circa 1934, Dry Tortugas, Florida (C. E. Peterson, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Although water quality was a challenge for members of the regiment at both of their duty stations in Florida throughout 1863, it was particularly problematic for the 47th Pennsylvanians who were stationed at Fort Jefferson. According to Schmidt:

‘Fresh’ water was provided by channeling the rains from the city’s barbette through channels in the interior walls, to filter trays filled with sand; and finally to the 114 cisterns located under the fort which held, 1,231,000 gallons of water. The cisterns were accessible in each of the first level cells or rooms through a ‘trap hole’ in the floor covered by a temporary wooden cover…. Considerable dirt must have found its way into these access points and was responsible for some of the problems resulting in the water’s impurity…. The fort began to settle and the asphalt covering on the outer walls began to deteriorate and allow the sea water (polluted by debris in the moat) to penetrate the system…. Two steam condensers were available … and distilled 7000 gallons of tepid water per day for a separate system of reservoirs located in the northern section of the parade ground near the officers [sic, officers’] quarters. No provisions were made to use any of this water for personal hygiene of the [planned 1,500-soldier garrison force]….

As a result, the soldiers stationed there washed themselves and their clothes, using saltwater from the ocean. As if that weren’t difficult enough, “toilet facilities were located outside of the fort,” according to Schmidt:

At least one location was near the wharf and sallyport, and another was reached through a door-sized hole in a gunport and a walk across the moat on planks at the northwest wall…. These toilets were flushed twice each day by the actions of the tides, a procedure that did not work very well and contributed to the spread of disease. It was intended that the tidal flush should move the wastes into the moat, and from there, by similar tidal action, into the sea. But since the moat surrounding the fort was used clandestinely by the troops to dispose of litter and other wastes … it was a continuous problem for Col. Alexander and his surgeon.

Second-tier casemates, lighthouse keeper’s house, sallyport, and lean-to structure, Fort Jefferson, Dry Tortugas, Florida, late 1860s (U.S. National Park Service and National Archives, public domain).

As for daily operations in the Dry Tortugas, there was a fort post office and the “interior parade grounds, with numerous trees and shrubs in evidence, contained officers’ quarters, [a] magazine, kitchens and out houses,” per Schmidt, as well as “a ‘hot shot oven’ which was completed in 1863 and used to heat shot before firing.”

Most quarters for the garrison … were established in wooden sheds and tents inside the parade [grounds] or inside the walls of the fort in second-tier gun rooms of ‘East’ front no. 2, and adjacent bastions … with prisoners housed in isolated sections of the first and second tiers of the southeast, or no. 3 front, and bastions C and D, located in the general area of the sallyport. The bakery was located in the lower tier of the northwest bastion ‘F’, located near the central kitchen….

Additional Duties: Diminishing Florida’s Role as the “Supplier of the Confederacy”

In addition to the strategic role played by the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers in preventing foreign powers from assisting the Confederate Army and Navy in gaining control over federal forts in the Deep South, the regiment was also called upon to play an ongoing role in weakening Florida’s abilities to supply and transport food and troops throughout areas held by the Confederate States of America.

Prior to intervention by the Union Army and Navy, the owners of plantations and livestock ranches, as well as the operators of small, family farms across Florida, had been able to consistently furnish beef and pork, fish, fruits, and vegetables to Confederate troops stationed throughout the Deep South during the first year of the American Civil War. Large herds of cattle were raised near Fort Myers, for example, while orchard owners in the Saint John’s River area were actively engaged in cultivating sizeable orange groves (while other types of citrus trees were found growing throughout more rural areas of the state).

Florida was also a major producer of salt, which was used as a preservative for food. As a result, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and other Union troops across Florida were ordered to capture or destroy salt manufacturing facilities in order to further curtail the enemy’s access to food.

But they were undertaking all of those duties in conditions that were far more challenging than any they had previously faced (and that were far more challenging than what many other Union troops were facing up north). The weather was frequently hot and humid as spring turned to summer, mosquitos and other insects were an ever-present annoyance (and serious threat when they were carrying tropical diseases) and there were also scorpions and snakes that put the men’s health at further risk.

As part of their efforts to ensure the efficacy of their ongoing operations, regimental officers periodically tweaked the assignments of individual companies during that year of garrison duty. One of those changes occurred on 16 May 1863 when D Company Captain Henry D. Woodruff and his men marched to the wharf at Fort Jefferson and climbed aboard yet another ship — this time for their return to Fort Taylor in Key West, where they resumed garrison duties under the command of Colonel Tilghman H. Good.

Four days later, enlisted members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were finally given eight months’ worth of their back pay — a significant percentage of which was quickly sent home to family members who had been struggling to make ends meet.

Despite all of these hardships, when members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were offered the opportunity to re-enlist during the fall of 1863, more than half of the regiment’s personnel did so without hesitation.

The year of 1863 had also proven to be an important one for Private Joseph Benson Shaver. Whether it was the isolation that he and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians faced while stationed in the Dry Tortugas or the ugly realities of chattel slavery and the carnage of battle that he had witnessed while stationed in South Carolina, he decided to immerse himself in religious studies when not on duty and was subsequently “converted” at the age of nineteen, according to later accounts of his life.

* Note: At some point during his tenure of service, Private Joseph Benson Shaver was assigned to duties on Morris Island in Charleston County, South Carolina, according to a family history written by the Reverend Charles Barnett Shaver during the 1950s. Per that account, it was on Morris Island that the Reverend Joseph Benson Shaver “was converted religiously, and was inspired to preach the gospel.” However, although Reverend Charles Shaver stated in that account that his ancestor, Joseph Benson Shaver, had experienced a conversion in 1863 “during the siege of Charleston,” researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story currently believe that Joseph B. Shaver’s spiritual awakening may have occurred earlier — in 1862 — while the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was stationed in Beaufort and Hilton Head, South Carolina and was being sent out, periodically, on expeditions to various islands nearby. (Or, that awakening may have even occurred at an entirely different location altogether. Accounts of 47th Pennsylvania duty assignments on Morris Island appear not to have been published in American Civil War-era newspapers until the summer of 1865 — at least two months after Private Joseph B. Shaver was honorably discharged from the regiment.)

1864

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers experienced yet another significant change when members of the regiment were ordered to expand the Union’s reach by sending part of the regiment north to retake possession of Fort Myers, a federal installation that had been abandoned in 1858, following the federal government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. In response, Captain Richard Graeffe and a group of soldiers from Company A traveled north, captured the fort and began conducting cattle raids to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across Florida. They subsequently turned the fort into their base of operations — and into a shelter for pro-union supporters, Confederate Army deserters and men and women who wanted to escape from enslavement.

Red River Campaign

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had begun preparing for the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer, the Charles Thomas, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by the men from Companies E, F, G, and H.

Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost-fully-reunited regiment moved by train to Brashear City (now Morgan City, Louisiana) before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the U.S. Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps (XIX Corps), and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks. (Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the soldiers from Company A were assigned to detached duty while awaiting transport that enabled them to reconnect with their regiment at Alexandria, Louisiana on 9 April).

From 14-26 March, the 47th passed through New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington while en route to Alexandria and Natchitoches. Often short on food and water, the regiment encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day, marching until mid-afternoon.

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division, sixty members of the 47th were cut down on 8 April during the volley of fire unleashed in the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads. The fighting waned only when darkness fell. Exhausted, those who were uninjured collapsed between the bodies of the gravely wounded and dead. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate Major-General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner and son of Zachary Taylor, former president of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault during what has since become known as the Battle of Pleasant Hill.

Once again casualties were severe. Among the men from D Company felled that day were Privates Ephraim Clouser, who had been shot in his right knee, Peter Petre, who had been wounded in the side, Samuel Wagner, and Joseph Benson Shaver, who had been severely wounded above the elbow of his left arm.

* Note: During a Memorial Day address that he would deliver in Hazleton, Pennsylvania — a quarter of a century after that Louisiana battle, the Reverend Joseph B. Shaver reflected on that day’s events:

It is in the Providence of God that we are alive. We bared our breasts to the same storm of shot and shell which swept our comrades down. I remember with sad distinctness when he who had marched side by side with me, for more than eighteen months, fell on my right, and my own arm dropped by my side like a lump of lead because there was lead in it.

Initially treated by regimental surgeons near the battlefield where he was wounded, Private Joseph Shaver was transported to a Union General Hospital in the city of New Orleans, along with Privates Petre and Wagner, where they were given more advanced care. Tragically, Private Wagner, who was subsequently discharged via a surgeon’s certificate of disability in late May 1864, died when the Union Army ship that was transporting him north (the U.S. Pocahontas) collided with another ship (the City of Bath) and sank off the coast of Cape May, New Jersey on 1 June 1864.

Equally tragic, Private Clouser, who had been captured by Rebel troops with more than a dozen other 47th Pennsylvanians, was subsequently marched more than one hundred and twenty-five miles southwest to Camp Ford, the largest Confederate States prison camp west of the Mississippi River, where he languished in captivity as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on 25 November 1864. (Subsequently confined to the Union Army’s hospital system, he was an emotionally-scarred shell of his former self who would later die by suicide.)

The outcome for Private Shaver, however, was ultimately a better one.

A Long Recovery

Map of key 1864 Red River Campaign locations, showing the battle sites of Sabine Cross Roads, Pleasant Hill and Mansura in relation to the Union’s occupation sites at Alexandria, Grand Ecore, Morganza, and New Orleans (excerpt from Dickinson College/U.S. Library of Congress map, public domain).

Because his arm was so severely wounded during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Private Joseph Benson Shaver missed out on the other events of the 1864 Red River Campaign in which his D Company comrades took part, including the Affair at Monett’s Ferry (23 April), the construction of Bailey’s Dam near Alexandria (26 April-12 May) and the Battle of Mansura near Marksville (16 May).

Moving on after that final battle, Private Shaver’s fellow 47th Pennsylvanians were given time to rest at a large Union Army encampment at Morganza, Louisiana in June before they were ordered to head for New Orleans, where Private Shaver was waiting for them. (They finally arrived in the city on 20 June.)

On 4 July, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers received orders to return to the East Coast. Three days later, they began loading their men onto ships, a process that unfolded in two stages. Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I boarded the U.S. Steamer McClellan on 7 July and steamed away that day, while the members of Companies B, G and K remained behind, awaiting transport. (The latter group subsequently departed aboard the Blackstone, weighing anchor and sailing forth at the end of that month.)

As a result of this twist of fate, Private Joseph Benson Shaver may have been one of the 47th Pennsylvania’s “early travelers” who subsequently had the good fortune to have a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln on 12 July 1864. That group of 47th Pennsylvanians then took part in the mid-July Battle of Cool Spring near Snicker’s Gap, Virginia; Private Shaver would not have been present on the field that day, however, because “his wounded arm [still] prevented him from fighting,” according to the Reverend Charles Barnett Shaver, who researched and wrote a biography of Joseph B. Shaver during the 1950s.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Halltown Ridge, shown here in this 1884 photograph, where Union Army troops were entrenched after Major-General Philip Sheridan took command of the Middle Military Division on 7 August 1864 (Thomas Dwight Biscoe, 2 August 1884, courtesy of Southern Methodist University; click to enlarge).

Attached to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah beginning in August, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was assigned to defensive duties in and around Halltown, Virginia during the opening days of that month, and then engaged in a series of back-and-forth movements over the next several weeks between Halltown, Berryville, Middletown, Charlestown, and Winchester as part of a “mimic war” being waged by the Union forces of Major-General Philip H. Sheridan with those commanded by Confederate Lieutenant-General Jubal Early.

From 3-4 September 1864, they took on Early’s Confederates again — this time in the Battle of Berryville. That month then also saw the departure of several 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers who had served honorably, including Company D’s Captain Henry Woodruff, First Lieutenant Samuel Auchmuty, Sergeants Henry Heikel and Alex Wilson, and Corporals Cornelius Stewart and Samuel A. M. Reed — many of whom mustered out on 18 September 1864, upon expiration of their respective service terms.

Those members of the 47th who remained on duty were about to engage in their regiment’s greatest moments of valor, but, once again, Private Joseph Benson Shaver would be kept on the sidelines by his wounded arm, according to the Reverend Charles B. Shaver. (He was, however, able to render moral support to his Union Army comrades, before and after their combat experiences.)

Battles of Opequan and Fisher’s Hill, September 1864

Together with other regiments under the command of Union Major-General Philip H. (“Little Phil”) Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, commander of the 19th Corps, the members of Company D and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers helped to inflict heavy casualties on Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate forces at Opequan (also spelled as “Opequon” and referred to as “Third Winchester”). The battle is still considered by many historians to be one of the most important during Sheridan’s 1864 campaign; the Union’s victory here helped to ensure the reelection of President Abraham Lincoln.

The 47th Pennsylvania’s march toward destiny at Opequan began at 2 a.m. on 19 September 1864 as the regiment left camp and joined up with others in the Union’s 19th Corps. After advancing slowly from Berryville toward Winchester, the 19th Corps became bogged down for several hours by the massive movement of Union troops and supply wagons, enabling Early’s men to dig in. After finally reaching the Opequan Creek, Sheridan’s men came face to face with the Confederate Army commanded by Early. The fighting, which began in earnest at noon, was long and brutal. The Union’s left flank (6th Corps) took a beating from Confederate artillery stationed on high ground.

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union Army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces, Battle of Opequan, 19 September 1864 (Kurz & Allison, circa 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania and the 19th Corps were directed by Brigadier-General William Emory to attack and pursue Major-General John B. Gordon’s Confederate forces. Some success was achieved, but casualties mounted as another Confederate artillery group opened fire on Union troops trying to cross a clearing. When a nearly fatal gap began to open between the 6th and 19th Corps, Sheridan sent in units led by Brigadier-Generals Emory Upton and David A. Russell. Russell, hit twice — once in the chest, was mortally wounded. The 47th Pennsylvania opened its lines long enough to enable the Union cavalry under William Woods Averell and the foot soldiers of General George Crook to charge the Confederates’ left flank.

Afterward, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were sent out on skirmishing parties before making camp at Cedar Creek. Moving forward, they would continue to distinguish themselves in battle, but would do so without two more of their respected commanders: Colonel Tilghman Good, founder of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers; and Good’s second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel George Alexander, who mustered out from 23-24 September upon the expiration of their respective terms of service.

Fortunately, they were replaced by others equally admired both for their temperament and their front line experience: Second Lieutenant George Stroop, who was promoted to lead Company D, and John Peter Shindel Gobin, Charles W. Abbott and Levi Stuber, who ultimately became the three most senior leaders of the regiment.

Battle of Cedar Creek, October 1864

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, “Surprise at Cedar Creek,” captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle-pit positions, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

It was during the fall of 1864 that Major-General Philip Sheridan began the first of the Union’s true “scorched earth” campaigns, starving the enemy into submission by destroying Virginia’s crops and farming infrastructure. Viewed through today’s lens of history as inhumane, the strategy claimed many innocents — civilians whose lives were cut short by their inability to find food. This same strategy, however, almost certainly contributed to the further turning of the war’s tide in the Union’s favor during the Battle of Cedar Creek on 19 October 1864. Successful throughout most of their engagement with Union forces at Cedar Creek, Early’s Confederate troops began peeling off in ever growing numbers to forage for food, thus enabling the 47th Pennsylvania and others under Sheridan’s command to rally.

From a military standpoint, it was another impressive, but heartrending day. During the morning of 19 October, Early launched a surprise attack directly on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. Early’s men were able to capture Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles — all while pushing seven Union divisions back. According to Bates:

When the Army of West Virginia, under Crook, was surprised and driven from its works, the Second Brigade, with the Forty-seventh on the right, was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat…. Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions, without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers, as he road rapidly past them – “Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!’”

Sheridan Rallying His Troops, Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

The Union’s counterattack punched Early’s forces into submission, and the men of the 47th were commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas who, in 1892, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked” that day. Bates described the 47th’s actions:

When the final grand charge was made, the regiment moved at nearly right angles with the rebel front. The brigade charged gallantly, and the entire line, making a left wheel, came down on his flank, while engaging the Sixth Corps, when he went “whirling up the valley” in confusion. In the pursuit to Fisher’s Hill, the regiment led, and upon its arrival was placed on the skirmish line, where it remained until twelve o’clock noon of the following day. The army was attacked at early dawn…no respite was given to take food until the pursuit was ended.

Once again, the casualties for the 47th were high. Sergeant William Pyers, the C Company man who had so gallantly rescued the flag at Pleasant Hill was cut down and later buried on the battlefield. Corporal Edward Harper of Company D was wounded, but survived, as did Corporal Isaac Baldwin, who had been wounded earlier at Pleasant Hill. Even Perry County resident and Regimental Chaplain William Rodrock of Perry County suffered a near miss as a bullet pierced his cap.

And, once again, Private Shaver had been sidelined by his wounded arm, which was still on the mend. According to the Reverend Charles B. Shaver, “The wounded arm prevented him from fighting on the battle fields, but he served in the army in the headquarters of the First Brigade, Second Division of the Tenth Army Corps.”

Following these major engagements, the 47th was ordered to Camp Russell near Winchester from November through most of December. On 14 November, Second Lieutenant George Stroop was promoted to the rank of captain.

Rested and somewhat healed, the 47th was then ordered to outpost and railroad guard duties at Camp Fairview in Charlestown, West Virginia five days before Christmas.

1865 — 1866

Still stationed at Camp Fairview in West Virginia as the New Year of 1865 dawned, members of the regiment continued to patrol and guard key Union railroad lines in the vicinity of Charlestown, while other 47th Pennsylvanians chased down Confederate guerrillas who had made repeated attempts to disrupt railroad operations and kill soldiers from other Union regiments.

Assigned in February 1865 to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers continued to perform their guerrilla-fighting duties until late March, when they were ordered to head back to Washington, D.C., by way of Winchester and Kernstown, Virginia.

Joyous News and Then Tragedy

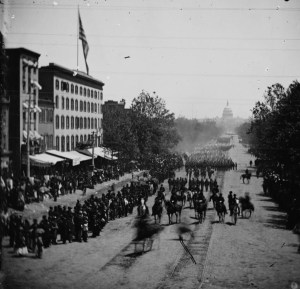

Spectators gather for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, beside the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half-staff following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

As April 1865 opened, the battles between the Army of the United States and the Confederate States Army intensified, finally reaching the decisive moment when the Confederate troops of General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox on 9 April.

The long war, it seemed, was finally over. Less than a week later, however, the fragile peace was threatened when an assassin’s bullet ended the life of President Abraham Lincoln. Shot while attending an evening performance of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre on 14 April 1865, he had died from his wound at 7:22 a.m. the next morning.

Shocked, and devastated by the news, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were given little time to mourn their beloved commander-in-chief before they were ordered to grab their weapons and move into the regiment’s assigned position, from which it helped to protect the nation’s capital and thwart any attempt by Confederate soldiers and their sympathizers to re-ignite the flames of civil war that had finally been stamped out.

So key was their assignment that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were not even allowed to march in the funeral procession of their slain leader. Instead, they took part in a memorial service with other members of their brigade that was officiated by the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental chaplain, the Reverend William D. C. Rodrock.

Present-day researchers who read letters sent by 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers to family and friends back home in Pennsylvania during this period, or post-war interviews conducted by newspaper reporters with veterans of the regiment in later years, will learn that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were collectively heartbroken by Lincoln’s death and deeply angry at those whose actions had culminated in his murder. Researchers will also learn that at least one member of the regiment, C Company Drummer Samuel Hunter Pyers, was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train, while other members of the regiment were assigned to guard duty at the prison where the key assassination conspirators were being held during the early days of their imprisonment and trial, which began on 9 May 1865.

19th Corps, Army of the United States, Grand Review of the Armies, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May 23, 1865 (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

The home base of the regiment during this phase of duty was Camp Brightwood, which was located in the Brightwood section of Washington, D.C. Attached to Dwight’s Division of the 2nd Brigade of the U.S. Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers also participated in the Union’s Grand Review of the National Armies, which took place in Washington, D.C. on 23 May 1865.

Eight days later, on 1 June 1865, Private Joseph Benson Shaver was officially mustered out of service by General Orders, No. 53, issued by Headquarters of the U.S. Army’s Middle Military Division.

Return to Civilian Life

Following his honorable discharge from the military, Joseph Benson Shaver returned to Pennsylvania, where he then embarked on his new path in life by enrolling for religious studies at the Dickinson Seminary in Williamsport, Lycoming County, Pennsylvania. Following his graduation from the program, he began his practical training under the guidance of the presiding elder of that city’s Mulberry Methodist Episcopal Church on 22 October 1865. He then received further training under the guidance of the presiding elder in 1867,” as a traveling member of the Methodist Episcopal Church’s Newport Circuit, according to Shaver Family records.

Per The Morning Press in Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania, Joseph Benson Shaver then “entered the ministry in the East Baltimore conference in March, 1868. In 1869 he became a member of the Central Pennsylvania conference at its organization,” and was subsequently assigned to serve the Methodist Episcopal congregations in Gettysburg (1868) and New Cumberland (1869-1870).

Officially ordained as a deacon during a ceremony that was officiated by Bishop Ames on 10 March 1870, he continued to minister to his flock in New Cumberland until he was re-assigned to the Methodist Episcopal Church in Greencastle in 1871. Designated as an elder by Bishop Simpson on 24 March 1872, he was then transferred to the Methodist Episcopal Church in Thompsontown.

On 20 June 1872, the Reverend Joseph Benson Shaver wed Emma Jane Mumper (1850-1936), a recent college graduate and resident of Dillsburg, York County, Pennsylvania who was a daughter of York County native and higher education advocate John Mumper (1817-1886) and Elizabeth Ann (McAllister) Mumper (1830-1879), a native of New Buffalo in Perry County, Pennsylvania. Their wedding ceremony took place at the Dillsburg Methodist Church.

Less than a year later, the Reverend Joseph B. Shaver was assigned to pastor the Methodist Episcopal congegration in Osceola Mills, Clearfield County, Pennsylvania. Their first daughter, Elizabeth Linn Shaver (1873-1950), who became known to family and friends as “Lizzie,” was subsequently born in Osceola Mills on 19 September 1873.

Family Life and Professional Success

As his career progressed, the Reverend Joseph Benson Shaver was appointed as the minister of Methodist Episcopal congregations throughout the Bedford Circuit (1875-1876) and in Milesburg (1877-1879) and Hollidaysburg (1880-1882), where he and his wife welcomed the birth of their second daughter, Mary Mumper Shaver (1883-1942), who opened her eyes for the first time in Hollidaysburg on 12 September 1883.

Transferred to the Methodist Episcopal Church in Curwensville in 1883, this period of his life was a stable one; he was allowed to continue his ministry there until 1886, when he was reassigned to the First Methodist Church in Altoona — a post he held through 1888.

Transferred to the Methodist Episcopal Church in Hazleton in 1889, he and his family remained in that community through 1892. Transferred to St. Paul’s Methodist Church in Danville in 1893, he held that post through 1895, and was subsequently transferred to the Pine Street Methodist Episcopal Church in Williamsport in 1896, remaining there through 1901.

Whispering words of comfort to the dying and those who mourned the passing of loved ones, he also delivered sermons from pulpits that sometimes made his listeners reflect on their perceived shortcomings but more often inspired them — and shook them from their apathy and timidity to right wrongs whenever and wherever they found them.

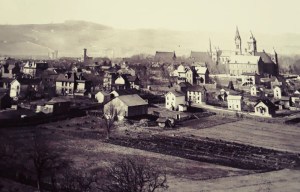

St. Patrick’s Day parade participants pass in front of St. Gabriel’s Church in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, March 1899 (public domain).

Among his most memorable speeches was a Memorial Day address that he delivered in Hazleton in May 1889, during which he said:

From the day when Moses and Aaron, plead in the presence of the tyrant Pharaoh, to the days when Leonidas with his three hundred Spartans stood in the pass of Thermopylae, on to the days when Patrick Henry burst the grave of freedom with his utterances of fire, and on to the days when Abraham Lincoln by one stroke of his pen broke the fetters of enchained millions, the struggles and triumphs of this spirit have been the burden of the world’s history, and inspiration of its song. This is the spirit of liberty. But in this practical world a spirit cannot reach its highest usefulness unless embodied. It was therefore the work of the American Congress to embody this spirit in the Constitution…. And rightly did the great English Statesman declare it to be “The most wonderful work ever struck off at a given time by the brain and purpose of man.”

Not only must this spirit be embodied, but embodied, it must be protected.

* Note: To read the full text of Reverend Shaver’s Decoration Day address, see “Memorial Oration” by the Reverend Joseph Benson Shaver.

Reverend Joseph Shaver’s wife was most certainly there in the crowd that day, supporting her husband as she had throughout their marriage. A formidable individual in her own right, she may very well have even been involved beforehand — reviewing and editing the rough drafts of his address and then serving as his “sounding board” as he practiced and honed his delivery. According to the Reverend Charles B. Shaver, “Emma Jane Mumper Shaver was a scholarly and a fluent and interesting conversationalist. Her enunciation was distinct and concise.”

Illness, Death and Interment

The final ministerial appointment for Reverend Joseph B. Shaver was awarded shortly before his death. Assigned as pastor of the Trinity Methodist Episcopal Church in Lock Haven, Clinton County, he arrived there in 1902.

Sometime around this same time, his physician determined that he had developed diabetes. Prompted by his condition to reduce his workload, the Reverend Doctor Joseph B. Shaver eventually became so ill that he was compelled by his failing body to leave his ministry in Lock Haven and return to Luzerne County, where he could be cared for at his daughter’s home in Hazleton in May 1903.

Sadly, his sojourn there was a brief one. He died there at the age of fifty-eight at 1:00 a.m. on 19 November 1903. So respected and beloved was he at the time of his passing that he was honored during multiple funeral services and memorial events. His first funeral, which was held at St. Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Hazleton on Sunday, 22 November, was described as follows by Danville’s Montour American newspaper:

The memorial service at St. Paul’s M. E. church Sunday in memory of the late Rev. Joseph B. Shaver, D.D., was attended by a very large congregation. Rev. Harry Curtin Harmon, the pastor, preached a very effective sermon founding his remarks on Ephesians 6:21: “He was a brother beloved and a faithful minister of Jesus Christ.”

Rev. Harman began by saying that there is no passage of scripture between the lids of the Bible which more accurately expresses his estimate of Dr. Shaver’s character than the one just announced…. Dr. Shaver was 35 years an effective minister in the Methodist Episcopal church. During those years he served 14 different churches as pastor, the average term of each pastorate being 2 1/2 years [two and one-half years]. When he began his ministry the time limit was two years. Gradually the limit increased to 3 years and then to 5 years, the last general conference removing the time limit entirely. The significant fact about Dr. Shaver’s ministry is that he remained with each church he served the full limit, his pastorate of Pine Street church, Williamsport, coming under the unlimited term. He remained in that church for six years and could have remained longer had he himself so desired.

His ministerial character was the mutual product of self acquired knowledge, wide reading, a profound knowledge of men, great wealth of experience and of divine grace. God only makes preachers, calls them into the ministry and always honors their conscientious and unselfish devotion to duty.

Dr. Shaver was preeminently an evangelistic preacher. The records of St. Paul’s church show that more people were converted and joined the church under Dr. Shaver’s pastorate of 3 years than under any other pastor with the exception of one. As a pastor he was the embodiment of the completest ideal. To him the delicate and sometimes difficult work of pastoral visitation was easily and inspiringly performed. He was always a welcome visitor in the homes of his people and left those homes better for his having been there. To him man’s emotional nature was as sacredly divine as his thought life. He was sympathetic, gentle, always. In him gentleness was a source of superb strength. He knew that a gentle man is always a strong man.

He was a veteran soldier of the Civil War, responding early in the inception of that war to his country’s call. Among his comrades in the army he was held in growing esteem. He had no sympathy for and but little patience with any sentiment which lacked appreciation for the boys in blue. Patriotism was a constituent element strongly developed in his Christian character. He belonged to the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and with his company endured the privations and hardships involved in the struggle for liberty.

He was an ardent Mason and among the craft of that honorable institution in this city he was greatly esteemed and exceedingly popular. He was one of the men who mingled freely with his brethren in the work of the lodge and in the social functions incident thereto, who always maintained in the confidence of his brethren the dignity of his Christian and ministerial character.

His death was as peaceful and triumphant as his life had been useful and helpful. “Let me die the death of the righteous man; let my last end be like his.”

Following that funeral in Hazleton, his remains were transported to Dillsburg in York County, where a second service was held on 20 November at his wife’s former home, which was described by his obituary in Harrisburg’s Patriot newspaper as “the old Mumper mansion, half a mile from the Dillsburg and Mechanicsburg Junction.”

Rev. Mr. Durstine, pastor of Dillsburg M. E. Church, had charge of the services.

Rev. Dr. S. C. Swallow, of Harrisburg, preached the sermon after the Scriptures had been read by Rev. C. V. Hartzell, and prayer had been offered by Rev. George M. Hoke, of New Cumberland. Rev. E. A. Pyers, pastor of Mechanicsburg M. E. Church, pronounced the benediction at the grave.

Mr. Shaver served three years in the Civil War, and wore the button of the G. A. R. He carried the scars of the wounds received in that sanguinary conflict, and was highly esteemed by his fellow soldiers. He has filled some of the most important pastoral charges of his conference, among them Hollidaysburg, Hazleton, Danville, Williamsport and Lock Haven. He was filling his second year at the latter appointment when stricken with diabetes. He was a popular, efficient and faithful man in all the relations of life. He is survived by a wife and two daughters.

Rev. Shaver was then laid to rest at the Mount Zion Church Cemetery in Churchtown, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. His loss continued to be felt in church congregations and communities across the nation, as evidence by reports transmitted by the Associated Press transmitted to newspapers across and beyond the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

What Happened to Rev. Joseph Benson Shaver’s Siblings?

Following his marriage to Anna L. Davis in 1875, John L. Shaver welcomed the birth of son David Oscar Shaver (1876-1949) in Bedford County, Pennsylvania on 19 December 1876. The trio subsequently settled in the city of Altoona in Blair County, Pennsylvania in 1886. It was there that John Shaver began his long career with the Pennsylvania Railroad Company (P.R.R.). His son, David, grew up to become a pharmacist in Altoona. Ailing with acute choleocystitis, John L. Shaver died from complications related to that disease at the age of seventy-nine in Altoona on 21 September 1922. Following funeral services, he was laid to rest at that city’s Rose Hill Cemetery.

Following his marriage to Susan Little Smeigh, Samuel Cass Shaver also settled in Altoona with his wife and also worked for the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. His son Arthur Linn Shaver (1886-1909) was born in 1866. Ailing with uremia, Samuel C. Shaver died at the Altoona Hospital on 2 March 1923 — just eleven days before his seventy-fifth birthday and was also buried at Altoona’s Rose Hill Cemetery.

Following his marriage to Anna Mary Bentzel in 1875, Albert Craig Shaver also settled with his wife in Altoona, where he was employed as a blacksmith. Together, they welcomed the births of: William Shaver (1876-1915), who was born on 7 July 1876; Emma Sophia Shaver (1878-1937), who was born on 27 July 1878 and later wed George Allison Stephens (1878-1956); Harry David Shaver (1881-1937), who was born in 1881; Thomas Blaine Shaver (1884-1948), who was born on 21 August 1884; Frank Harrison Shaver (1887-1957), who was born in 1887; Mary Shaver (1890-1890), who was just five weeks old when she died on 8 June 1890; Ella Shaver (1890-1892), who was just eighteen months old when she died on 13 August 1892; McKinley Shaver (1896-1938), who was born in 1896 and later served in the United States Navy during World War I; and an unnamed infant who was stillborn on 28 January 1901. Ailing with acute myocarditis, Albert Shaver died at the age of seventy-two in Altoona on 26 January 1927, and was also buried at Altoona’s Rose Hill Cemetery.

What Happened to Rev. Joseph Benson Shaver’s Wife and Daughters?

Following the death of her husband, Emma Jane (Mumper) Shaver relocated to the home of her daughter, Elizabeth (Shaver) Smith in White Plains, New York. Having survived her husband by more than three decades, Emma Shaver died in White Plains at the age of eighty-six, two days after Christmas in 1936. Following funeral services, she was laid to rest beside her husband at the Mount Zion Cemetery in Churchtown Cumberland County, Pennsylvania.

Well educated throughout her life, the Shavers’ youngest daughter, Mary Mumper (Shaver) Browne, graduated from the Dickinson Seminary in Williamsport, Pennsylvania in 1902, from the Woman’s College of Baltimore City (now Goucher College) in Baltimore, Maryland in 1906 and from the New York State Library School in Albany, New York in 1907.

She was then hired as an assistant librarian by the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania (1908) and as a librarian by John B. Stetson University in Deland, Florida (1908-1910). Subsequently hired by Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York as a cataloguer for its college library in 1911, she was employed as a classifier and cataloguer by 1917, and served as a member of that higher education institution’s library staff until 1924, when she joined the library faculty at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York.

The dome of Columbia University’s Low Library towered over the campus and the Hudson River well before Mary Mumper Shaver began working there (Low Library, Columbia University, New York City, New York, 1903, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Subsequently hired by Columbia University in New York City, New York as a member of its library school faculty in 1927, she was employed as an assistant professor at that university’s School of Library Service, and spent her summers teaching special courses at the Chautauqua School of Librarians in Chautauqua, New York and at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Her areas of expertise were bibliography, book selection, the history of books and printing, and reference services. Married in 1938 to Kermit Brown, an executive with the Thomas Mason Company in New York City, she died at her home in New York City on 31 January 1942.

Having wed attorney Frederick Lauderburn Smith (1864-1945) on 28 March 1894, the Shavers’ oldest daughter, Elizabeth (Shaver) Smith, welcomed the births of: Frederick Lauderburn Smith, II (1894-1942), who was born on Christmas Day in 1894 and later wed Charlotte Lucas on Christmas Day in 1927; Elizabeth Linn Smith (1896-1985), who was born on 14 June 1896 and later wed Bayard M. Green in June 1917, before divorcing him two years later and marrying Thomas F. Harris on 23 June 1923; and Nancy Linn Smith (1909-2008), who was born on 25 November 1909 and later married Robert P. Breckenridge on 26 September 1936. Widowed by her husband on 27 April 1945, Elizabeth (Shaver) Smith went on to live a long, full life, reportedly passing away at the age of seventy-seven in York County, Pennsylvania on 1 October 1950, according to Shaver family historians.

Sources:

- “100 Years of M. E. Pastors.” Hazleton, Pennsylvania: The Plain Speaker, 29 October 1937.

- Albert Craig Shaver (a younger brother of Joseph Benson Shaver), in Death Certificates (file no.: 3731, registered no.: 89, date of death: 26 January 1927). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania: Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- “Assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved online 21 May 2025.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of the Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- “Battleground National Cemetery: Battleround to Community — Brightwood Heritage Trail,” “Fort Stevens” and “Mayor Emery and the Union Army.” United States: Historical Marker Database, retrieved online 20 May 20 2025.

- “Battleground to Community: Brightwood Heritage Trail.” Washington, D.C.: Cultural Tourism DC, 2008.

- “Central Pennsylvania Conference of the M. E. Church.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury Gazette, 26 March 1870.

- Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866. Pennsylvania State Archives, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

- “Conference Appointments.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Harrisburg Daily Patriot, 22 March 1882.

- “Conference Appointments.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Patriot, 3 April 1901.

- “Conference Locates Its Ministers.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Patriot, 3 April 1902 (p. 4 of pp. 1 and 4).

- “Death of Rev. J. B. Shaver.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Daily Leader, 19 November 1903.

- “Death of Rev. J. B. Shaver.” Danville, Pennsylvania: Montour American, 19 November 1903.

- “Death of Rev. J. B. Shaver.” Scranton, Pennsylvania: The Scranton Republican, 18 November 1903.

- “Death of Rev. J. B. Shaver.” York, Pennsylvania: The York Daily, 18 November 1903.

- “Death of Rev. J. B. Shaver: Well Known Member of Central Pennsylvania Methodist Conference.” Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: Wilkes-Barre Semi-Weekly Record, 20 November 1903.

- “Dies in New York City” (obituary of Professor Mary Mumper Shaver Browne, a daughter of the Reverend Joseph Benson Shaver). Mahanoy City, Pennsylvania: The Record-American, 4 February 1942.

- “Dissatisfied With the Appointment.” Danville, Pennsylvania: The Danville News, 4 April 1902.

- “East Baltimore Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church.” Baltimore, Maryland: The Baltimore Sun, 18 March 1868.

- “Florida’s Role in the Civil War,” in Florida Memory. Tallahassee, Florida: State Archives of Florida.

- “Funeral of Rev. J. B. Shaver: Took Place at Mrs. Shaver’s Old Homestead Near Dillsburg Junction,” in “Obituary.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Patriot, 23 November 1903.

- “Funeral of the Rev. J. B. Shaver.” Altoona, Pennsylvania: Morning Tribune, 19 November 1903.

- “Grand Military Review: Streets Crowded with Spectators: Sherman Greeted with Deafening Cheers.” Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The Daily Post, 25 May 25 1865.

- Hain, Harry Harrison. History of Perry County, Pennsylvania. Including Descriptions of Indians and Pioneer Life from the Time of Earliest Settlement. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Hain-Moore Company, 1922.

- “In Memory of Dr. Shaver” (recounting of the commentary made about the Reverend Doctor Joseph Benson Shaver during his memorial service at St. Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Hazleton, Pennsylvania). Danville, Pennsylvania: Montour American, 26 November 1903.

- John Lynn Shaver (the older brother of Joseph Benson Shaver), in Death Certificates (file no.: 83002, registered no.: 553, date of death: 21 Septmber 1922). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania: Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- Joseph B. Shaver, in “The Tyrone Conference.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvanua: The Patriot, 19 March 1895.

- Linn, John (grandfather and head of household); Shaver, David (son-in-law of John Linn), Nancy (daughter of John Linn and wife of David Shaver), and John L., Joseph B. and Samuel C. (grandsons of John Linn and children of David and Nancy Shaver); Bowe, Susan; and Kisler, David, in U.S. Census (Madison Township, Pery County, Pennsylvania, 1850). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Mary Mumper Shaver (a daughter of the Reverend Joseph Benson Shaver), in The Vassarion, vol. 29, p. 26. Poughkeepsie, New York: Vassar College, 1917.

- Mary Mumper Shaver (a daughter of the Reverend Joseph Benson Shaver), in Vassar College Bulletin, vol. IX, no. 3, p. 5. Poughkeepsie, New York: Vassar College, May 1920.

- “Mary Shaver Browne Dead: Daughter of Former Local Pastor, Professor at Columbia University.” Hazleton, Pennsylvania: The Plain Speaker, 4 February 1942.

- “Memorials in Churches” (notices of memorial services planned statewide for the Rev. Joseph Benson Shaver). Hazleton, Pennsylvania: The Plain Speaker, 19 November 1903.

- Ministerial Institute Closed: The Most Successful Ever Held by the Central Pennsylvania Conference.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Patriot, 27 September 1895.

- “Mrs. Kermit D. Browne” (obituary of Mary Shaver Browne, a daughter of the Reverend Joseph Benson Shaver). Brooklyn, New York: Brooklyn Eagle, 3 February 1942.

- “Our Heroes! The Grand Review at Washington. Honor to the Brave. Immense Outpouring of the People. The Troops Reviewed by Gen. Grant.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Daily Telegraph, 23 May 1865.

- Pitman, Benn. The Assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and the Trial of the Conspirators. Cincinnati, Ohio and New York, New York: Moore, Wilstach & Boldwin, 1865.

- “Prominent Minister Dead.” Ebensburg, Pennsylvania: Mountaineer — Herald, 19 November 1903.

- “Rev. J. B. Shaver.” Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The Pittsburgh Post and The Pittsburgh Press, 18 November 1903.

- “Rev. J. B. Shaver,” in “Obituary.” Reading, Pennsylvania: The Reading Daily Times, 18 November 1903.

- “Rev. J. B. Shaver Dead.” Lancaster, Pennsylvania: The Lancaster Examiner, 18 November 1903.

- “Rev. J. B. Shaver Dead: By Associated Press to the Patriot.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Patriot, 18 November 1903.

- “Rev. Shaver Dead.” Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania: The Morning Press, 18 November 1903.

- “Review of the Armies; Propitious Weather and a Splendid Spectacle. Nearly a Hundred Thousand Veterans in the Lines.” New York, New York: The New York Times, 24 May 1865, front page.

- Rodrock, Rev. William D. C. Chaplain’s Reports (47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, 1863-1865). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Roster of the 47th P. V. Inf.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 26 October 1930.

- Samuel C. Shaver (a younger brother of Joseph Benson Shaver), in Death Certificates (file no.: 31981, registered no.: 191, date of death: 2 March 1923). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania: Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- Samuel C. Shaver (death notice of the younger brother of Joseph Benson Shaver), in “Railroad Notes.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Harrisburg Telegraph, 5 March 1923.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- Shaver, Charles Barnett and John H. Shaver. The Shaver Family. Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1958-1959 and reissued with additional history by John H. Shaver in 2004.

- Shaver, Mary M. Syllabus for the Study of History of Books and Printing for Use in Connection with Book Arts 281, Third Edition. New York, New York: School of Library Service, Columbia University, 1939.

- Shaver, Rev. Joseph B. “Memorial Oration,” in “Our Departed Heroes.” Hazleton, Pennsylvania: The Hazleton Sentinel, 30 May 1889.

- Steers, Edward Jr. and Harold Holzer. The Lincoln Assassination Conspirators: Their Confinement and Execution, as Recorded in the Letterbook of John Frederick Hartranft. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: LSU Press, 2009.

- “The 47th P. V. in Action” (casualty report for the 1864 Red River Campaign Battles of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield and Pleasant Hill, Louisiana, 8-9 April 1864). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Patriot and Union, 29 April 1864.

- “The Final March: Grand Review of the Armies.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Park Service, retrieved online 20 May 2025.

- “The Grand Review: A Grand Spectacle Witnessed.” Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The Daily Post, 24 May 1865.

- “The Grand Review: Immense Crowds in Washington: Fine Appearance of the Troops: Their Enthusiastic Reception.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Daily Telegraph, 24 May 24 1865; and West Chester, Pennsylvania: The Record, 17 May 17 1865.

- “The Grand Review: The City Crowded with Visitors: Order of Corps, Divisions, Brigades and Regiments.” Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Daily Constitutional Union, 23 May 23 1865.

- “The History of the Forty-Seventh Regt. P. V.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Lehigh Register, 20 July 1870.

- “The Lincoln Conspirators,” in “Ford’s Theatre.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Park Service, retrieved online 21 May 21 2025.

- “Their Fields of Labor.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Patriot, 25 March 1896 (p. 5 of pp. 1 and 5).

- Trautman, Ray. A History of the School of Library Service: Columbia University, pp. 46 and 74. New York, New York: Columbia University Press, 1954.

- “Twenty-Eight Will Graduate from Seminary” (graduation announcement which mentions Joseph Benson Shaver’s daughter, Mary Mumper Shaver). Williamsport, Pennsylvania: Gazette and Bulletin, 7 June 1902.

- “Well Known Citizen and Veteran of Civil War Succumbs Yesterday” (obituary of John L. Shaver, the older brother of Joseph Benson Shaver). Altoona, Pennsylvania: Altoona Tribune, 22 September 1922.

You must be logged in to post a comment.