This house at the corner of Main and Carlisle streets in Landisburg, Perry County, Pennsylvania served as a stop along the Underground Railroad during the nineteenth century (public domain photo, circa 1900).

Born in Perry County, Pennsylvania on 22 February 1836, and baptized at the Presbyterian Church in Landisburg on 22 February 1837, George Washington Topley was a son of Landisburg, Perry County native Alexander Fullerton Topley (1805-1853) and Susannah (Ziegler) Topley (1805-1863), and the younger brother of: Ann Eliza Topley (1830-1906), who had been born in Landisburg on 7 November 1930, was known to family and friends as “Annie” and later wed Dr. J. P. Kimball; Catherine R. Topley (1831-1925), who had been born in Landisburg on 5 May 1830 (according to her obituary, or on 10 May 1831, according to other sources), later wed Charles R. Sponsler and was known to family and friends as “Kate”; and Mary Ellen Topley (1833-1912), who had been born on 13 October 1833 (alternate birth year: 1834) and later wed Isaiah McCaskey.

By the late 1830s, George Topley was no longer the baby of the family — thanks to the arrival of Lemuel Topley (1837-1885), who was born in Perry County in 1837 and would later also serve in the Union Army during the American Civil War (but with the 133rd Pennsylvania Volunteers and not the 47th Pennsylvania as George would).

Additional younger siblings then also arrived at the Topley’s Perry County home: William Albert Topley (circa 1840-1916), who was born circa 1840 and later wed Ida Glendora Mulford (1856-1930); Permelia Alinda Topley (1843-1924), who was born in 1843 and later wed William Henry Martin (1840-1919); and Addie F. Topley (1846-1880), who was born in 1846 and later wed Henry Wilson Sheibley.

Perry County Courthouse, New Bloomfield, Pennsylvania, circa 1860s (Hain’s History of Perry County, 1922, public domain).

By 1850, the Topleys were residing in the Borough of Bloomfield in Perry County, where their father had amassed personal property that was valued by that year’s federal census enumerator at twelve thousand four hundred dollars (the equivalent of more than half a million dollars in 2025). Tragically, their happy home was disrupted shortly thereafter by the untimely death of their father, Alexander, who passed away in New Bloomfield at the age of forty-seven on 9 June 1853.

By 1860, George W. Topley was employed as a farmer who resided at the New Bloomfield, Perry County home of his sister, Mary Ellen (Topley) McCaskey, and her husband, farmer Isaiah McCaskey. Like many of their fellow Pennsylvanians, they watched and worried as their nation descended into the darkness of disunion and civil war, beginning with the secession of South Carolina, on 20 December, from the United States of America.

American Civil War — 2nd Pennsylvania Volunteers

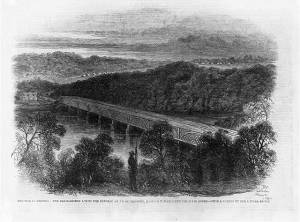

“Council of War” depicted “Generals Williams, Cadwallader, Keim, Nagle, Wynkoop, and Colonels Thomas and Longnecker” strategizing on the eve of the Battle of Falling Waters (Harper’s Weekly, 27 July 1861, public domain).

An early responder to President Abraham Lincoln’s 15 April 1861 call for state militia troops to defend the nation’s capital following the fall of Fort Sumter, George Washington Topley enrolled and mustered in on 20 April 1861 in Harrisburg, Dauphin County as a private with Company D of the 2nd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Military records described him as a twenty-five-year-old resident of New Bloomfield, Perry County.

Transported to Cockeysville, Maryland with his regiment the next day, via the Northern Central Railway, and then to York, Pennsylvania, Private Topley and the 2nd Pennsylvania remained in York until 1 June 1861 when they moved to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. There, they were attached to the 2nd Brigade (under Brigadier-General George Wynkoop), 2nd Division (under Major-General William High Keim), in the Union Army corps commanded by Major-General Robert Patterson.

Ordered to Hagerstown, Maryland on 16 June and then to Funkstown, the regiment remained in that vicinity until 23 June.

On 2 July, Private George W. Topley and his fellow 2nd Pennsylvania Volunteers served in a support role during the Battle of Falling Waters, Virginia — an encounter that would also see the participation of soldiers from other regiments who would, like Topley and the 2nd Pennsylvania’s Company D, later join the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers. One such unit engaged at Falling Waters was Company F of the 11th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

The Battle of Falling Waters, fought on 2 July 1861, was the first Civil War battle in the Shenandoah Valley. (A second battle with a different military configuration occurred there in 1863.) Also known as the Battle of Hainesville or Hoke’s Run, this first Battle of Falling Waters helped pave the way for the Confederate Army’s victory at Manassas (Bull Run) on 21 July, according to several historians. The vigorous Confederate effort, although unsuccessful, is believed to have been a factor in the tempering of Union General Robert Patterson’s combat assertiveness in later battles.

The next day, Private George W. Topley and his fellow 2nd Pennsylvanians occupied Martinsburg, Virginia. On 15 July, they advanced on Bunker Hill, and then moved on to Charlestown on 17 July before reaching Harper’s Ferry on 23 July. Three days later, on 26 July 1861, Private George Topley and his regiment were honorably discharged.

American Civil War — 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers

On 20 August 1861, at the age of twenty-five, George W. Topley re-enrolled for military service with the Union Army in Bloomfield, Perry County, Pennsylvania. He then re-mustered for duty at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County as a sergeant with the newly-formed 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry on 31 August 1861.

Following a brief training period in light infantry tactics, Sergeant George Topley and his company were sent by train with the 47th Pennsylvania to Washington, D.C. where they were stationed at “Camp Kalorama” on the Kalorama Heights near Georgetown, about two miles from the White House, beginning 20 September. Two days later, C Company Musician Henry D. Wharton penned these words to his hometown newspaper, the Sunbury American:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a setting [sic, set] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposefully erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so adapt [sic, wrapped] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on discovering they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.

Col. Good, who has command of our regiment, is an excellent man and a splendid soldier. He is a man of very few words, and is continually attending to his duties and the wants of the Regiment.

…. Our Regiment will now be put to hard work; such as drilling and the usual business of camp life, and the boys expect and hope for an occasional ‘pop’ at the enemy.

Chain Bridge across the Potomac above Georgetown looking toward Virginia, 1861 (The Illustrated London News, public domain).

Acclimated somewhat to their new life, the soldiers of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry finally became part of the Army of the United States when they were officially mustered into federal service on 24 September. Three days later, they were assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General Isaac Ingalls Stevens, which also included the 33rd, 49th and 79th New York regiments. By that afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were on the move again.

Ordered onward by Brigadier-General Silas Casey, the Mississippi rifle-armed 47th Pennsylvania infantrymen marched behind their Regimental Band until reaching Camp Lyon, Maryland on the Potomac River’s eastern shore. At 5 p.m., they joined the 46th Pennsylvania in moving double-quick (one hundred and sixty five steps per minute using thirty-three-inch steps) across the “Chain Bridge” marked on federal maps, and continued on for roughly another mile before being ordered to make camp.

The next morning, they broke camp and moved again. Marching toward Falls Church, Virginia, they arrived at Camp Advance around dusk. There, about two miles from the bridge they had crossed a day earlier, they re-pitched their tents in a deep ravine near a new federal fort under construction (Fort Ethan Allen). They had completed a roughly eight-mile trek, were situated close to the headquarters of Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith (also known as “Baldy”) and were now part of the massive U.S. Army of the Potomac (“Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Under Smith’s leadership, their regiment and brigade would help to defend the nation’s capital from the time of their arrival through late January when the men of the 47th Pennsylvania would be shipped south.

Once again, Company C Musician Henry Wharton recalled the regiment’s activities, noting, via his 29 September letter to the Sunbury American:

On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders.)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march the morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic, Lewinsville], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six tons of hay. A nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment….

The Big Chestnut Tree, Camp Griffin, Langley, Virginia, 1861 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Sometime during this phase of duty, as part of the 3rd Brigade, the 47th Pennsylvanians were moved to a site they initially christened “Camp Big Chestnut,” in reference to a large chestnut tree growing there. The site would eventually become known to them as “Camp Griffin,” and was located roughly ten miles from Washington, D.C.

On 11 October, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads. In a mid-October letter to his own family and friends, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin, the commanding officer of Company C, reported that Companies D, A, C, F, and I (the 47th Pennsylvania’s right wing) were ordered to picket duty after the regiment’s left-wing companies (B, E, G, H, and K) had been forced to return to camp by Confederate troops.

In his letter of 13 October, Musician Henry Wharton described the duties of the average 47th Pennsylvanian, as well as the regiment’s new home:

The location of our new camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic, chestnut] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets. Last night, however, they (the Rebels) calculated wide of their mark; some of the New York 33d boys were out on picket; some fourteen or fifteen shots were exchanged, when our side succeeded in bringing to the dust, (or rather mud,) an officer and two privates of the enemy’s mounted pickets. The officer was shot by a Lieutenant in Company H [?], of the 33d.

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually, but the hardest was on picket from last Thursday morning ’till Saturday morning – all the time four miles from camp, and both of the nights the rain poured in torrents, so much so that their clothes were completely saturated with the rain. They stood it nobly – not one complaining; but from the size of their haversacks on their return, it is no wonder that they were satisfied and are so eager to go again tomorrow. I heard one of them say ‘there was such nice cabbage, sweet and Irish potatoes, turnips, &c., out where their duty called them, and then there was a likelihood of a Rebel sheep or young porker advancing over our lines and then he could take take them as ‘contraband’ and have them for his own use.’ When they were out they saw about a dozen of the Rebel cavalry and would have had a bout with them, had it not been for … unlucky circumstance – one of the men caught the hammer of his rifle in the strap of his knapsack and caused his gun to fire; the Rebels heard the report and scampered in quick time….

On Friday morning, 22 October 1861, the 47th engaged in a divisional review, described by historian Lewis Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review that was monitored by the regiment’s founder and commanding officer, Colonel Tilghman H. Good — a formal inspection that was followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

As a reward — and in preparation for bigger things to come, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan obtained new Springfield rifles for every member of the 47th Pennsylvania.

1862

The City of Richmond, a sidewheel steamer which transported Union troops during the Civil War (Maine, circa late 1860s, public domain).

Ordered to move from their Virginia encampment back to Maryland, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862. Marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church, they were transported to Alexandria, where they boarded the steamship City of Richmond and sailed the Potomac River to the Washington Arsenal, where they disembarked and were re-equipped. Subsequently marched to the Soldiers’ Rest in Washington, D.C., they were fed and given the opportunity to relax there. The next afternoon, they were marched to the railroad station, where they hopped aboard a train from the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland.

Arriving around 10 p.m., they disembarked and were marched to a barracks at the United States Naval Academy, where they bedded down for the night. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January) loading their equipment and supplies onto the U.S.S. Oriental.

During the afternoon of 27 January, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers began boarding the Oriental, enlisted men first, and then, per the directive of Brigadier-General Brannan, they steamed away at 4 p.m. and headed for Florida, which, despite its secession from the United States remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of several key federal installations.

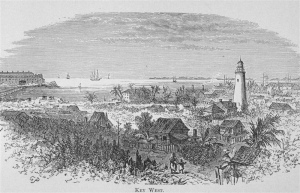

Lighthouse, Key West, Florida, early to mid-1800s (Florida for Tourists, Invalids, and Settlers, George M. Barbour, 1881, public domain).

Arriving in Key West, Florida by early February 1862, the men of Company D and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers disembarked and were ordered to pitch their tents on the beach, where they rested and were subsequently directed to their respective quarters inside and outside of Fort Taylor. Assigned to garrison the fort, they drilled daily in infantry and artillery tactics, began strengthening the fortifications of this key federal installation and also began making infrastructure improvements to the city by felling trees and building new roads.

During the weekend of 14 February, the regiment introduced itself to area residents via a parade through the city’s streets. That Sunday, the 47th Pennsylvanians began mingling with locals at area church services.

Among the lighter moments, the regiment commemorated the birthday of President George Washington with a parade, a special ceremony involving the reading of Washington’s farewell address to the nation (first delivered in 1796), the firing of cannon at the fort, and a sack race and other games on 22 February. The festivities resumed two days later when the Regimental Band hosted an officers’ ball at which “all parties enjoyed themselves, for three o’clock of the morning sounded on their ears before any motion was made to move homewards,” according to Musician Henry Wharton. This was then followed by a concert by the regimental band on Wednesday evening, 26 February.

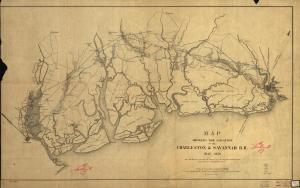

This 1856 map of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad shows the island of Hilton Head, South Carolina in relation to the towns of Beaufort and Pocotaligo (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Next ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina, from early June through July, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers camped near Fort Walker before relocating roughly thirty-five miles away in the Beaufort District in the U.S. Army’s Department of the South. Frequently assigned to hazardous picket duty north of their main camp, they faced an increased risk of enemy sniper fire. Despite this danger, though, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan” for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing,” according to historian Samuel P. Bates.

Detachments from the regiment were also assigned to the Expedition to Fenwick Island (9 July) and the Demonstration against Pocotaligo (10 July).

Bay Street Looking West, Beaufort, South Carolina, circa 1862 (Sam A. Cooley, 10th Army Corps, photographer, public domain).

On 1 September 1862, Sergeant George W. Topley was reduced to the rank of private by Colonel Tilghman H. Good, commanding officer of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers. By the end of that month, the majority of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantrymen would be given their first true taste of military expedition life when they took part in the capture of Saint John’s Bluff, Florida. By the end of October, multiple members of the regiment would be severely wounded or dead, following the Union’s failed efforts to destroy the Pocotaligo Bridge during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina on 22 October.

Sometime around this phase of duty for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Private George W. Topley was diagnosed by regimental physicians as having suffered a loss of hearing severe enough for him to be labeled as “deaf” — a designation which resulted in his honorable discharge from the regiment at its duty station in Beaufort, South Carolina, on a surgeon’s certificate of disability, on 7 December 1862.

Following his return home to Perry County, Pennsylvania, he worked as a farmer to support himself.

Return to Civilian Life (Winter 1862)

Following his honorable discharge, George W. Topley returned home to Perry County, Pennsylvania.

By the summer of 1863, as the federal government’s conscription program was drafting additional Pennsylvanians into military service, George W. Topley and his younger brother, William, were both documented as residents of New Bloomfield who were employed as tinners.

American Civil War — 2nd Pennsylvania, Provisional Artillery

Private George W. Topley’s grave, Poplar Grove National Cemetery, Dinwiddie County, Virginia (public domain).

On 17 February 1864, the now twenty-seven-year-old George Topley, re-enrolled for military service. He was re-mustered in that same day as a private with Company K of the 2nd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery (also known as the 112th Pennsylvania Volunteers). Military records at that time described him as being five feet, eight and one-half inches tall tall with brown hair, blue eyes and a light complexion. He subsequently connected with his regiment while it was engaged with other Union forces in protecting Washington, D.C.

On 20 April 1864, per Special Orders, No. 153 of the U.S. War Department, Private Topley was detached to the 2nd Pennsylvania Provisional Heavy Artillery. On 17 June 1864, he was killed in action in the Union’s ramp-up operations to the Siege of Petersburg, Virginia. Roughly twenty-seven years old when he was buried near where he fell at Avery’s Farm, his remains were later exhumed as part of the federal government’s effort to reinter all Union soldiers at national cemeteries. He remains at rest at the Poplar Grove National Cemetery in Dinwiddie County, Virginia.

What Happened to George Topley’s Mother and Siblings?

George W. Topley’s mother, Susannah (Ziegler) Topley filed for a U.S. Civil War Mother’s Pension on 20 December 1864. On 12 January 1865, she then completed her last will and testament with the assistance of her attorney, William A. Sponsler. In that will, she specified the equal distribution of her assets to her children Eliza (Topley) Kimball, who had married and been widowed by Dr. J. P. Kimball; Catharine (Topley) Sponsler, who was married to Charles R. Sponsler; Mary Ellen (Topley) McCaskey, who had married Isaiah McCaskey; Permelia (Topley) Martin, who had married William Martin; and Lemuel and Addie F. Topley, who were still single.

* Note: Researchers have not yet determined the dates and locations of Susannah (Ziegler) Topley’s death or burial.

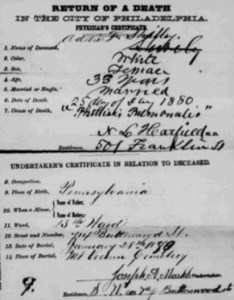

Physician’s death certificate for Addie F. (Topley) Sheibley, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1880 (Philadelphia City Archives, public domain).

Tragically, George W. Topley’s youngest sister, Addie F. (Topley) Sheibley, became one of several Topley siblings to die young. Married to former Perry County deputy sheriff Henry Wilson Sheibley at the Trinity Reformed Church in Philadelphia on 23 December 1868, she relocated with him to Philadelphia where, in 1869, the couple welcomed the birth of a daughter, Amelia, who appears to have died in childhood (because she was listed on federal census records for 1870 but not 1880). On 14 October 1874, the couple then also welcomed the birth of son John Edward Sheibley (1874-1947). But Addie (Topley) Sheibley would have less than six years to watch her son grow. Ailing with consumption (tuberculosis) during the late 1870s, Addie F. (Topley) became increasingly ill as her condition devolved into phthisis pulmonalis, a wasting-away condition common to tuberculosis patients. Following her death on 25 January 1880, she was laid to rest at Philadelphia’s Mount Vernon Cemetery.

Unlike George Topley, Lemuel Topley managed to survive the war. Hospitalized in Frederick, Maryland while serving with the 133rd Pennsylvania in November 1862, he was later reassigned to nursing duties at the Union’s McKim Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. Honorably discharged from his regiment on 26 May 1863, he wed Anna Amelia Douglas (1849-1927), who was known to family and friends as “Annie.” Together, they welcomed the births of: Florence Virginia Topley (1868-1958), who was born circa 1868; Grace Amelia Topley (1870-1950), who was born on 5 January 1870; Jessie E. Topley (1871-1962), who was born on 24 August 1871; Samuel Alexander Topley (1874-1937), who was born on 12 June 1874; Mary Catherine Topley (1875-1962), who was born on 25 October 1875); Annie H. Topley (1877-1963), who was born on 31 October 1877; William Douglas Topley (1879-1971), who was born on 21 October 1879; Sarah S. Topley (1882-1968), who was born on 15 January 1882; and Lemuel Cleveland Topley (1884-1949), who was born on 11 February 1884.

But, like his father, older brother and youngest sister, Lemuel Topley also suffered an untimely death. Following his passing at the age of roughly forty-seven in Arlington, Virginia on 6 October 1885, he was laid to rest at the Mount Olivet Methodist Church Cemetery in Arlington. His pregnant widow, Annie, then gave birth to their final child, Ruth E. Topley (1886-1890), in Arlington County on 22 February 1886. Sadly, Ruth subsequently died at the age of four in Arlington County (on 7 December 1890).

In contrast to those shocking deaths, George Topley’s older sister, Annie (Topley) Kimball, survived him by more than four decades. Following her passing at the age of seventy-five in New Bloomfield, Perry County on 8 April 1906, she was laid to rest at that community’s Bloomfield Cemetery.

Meanwhile, following her own marriage — to Charles R. Sponsler, George Topley’s sister, Catherine R. (Topley) Sponsler, who was known to family and friends as “Kate,” was welcoming the birth of a daughter who, sadly, also died at a young age. Widowed by her husband in 1880, Kate Sponsler subsequently relocated to the city of Baltimore in Maryland, where she resided for many years at the home of her sister, Permelia (Topley) Martin, who preceded her in death in 1924. Kate then returned home to Pennsylvania, and spent her remaining years in McVeytown, Mifflin County, where she died at the age of ninety-five on 26 January 1925. Following the return of her remains to Baltimore, funeral services were held in that city at 12:30 p.m. on 29 January, and Kate was then laid to rest at the Baltimore Cemetery. According to The Perry County Democrat, “‘Aunt Kate,’ as she was familiarly known, was a woman of rare charm of character and everybody who knew her loved and respected her.”

Following her marriage to William Henry Martin, George W. Topley’s younger sister, Permelia (Topley) Martin, relocated with him to Maryland, where their son, Charles S. Martin (1867-1955), was born in 1867. By the turn of the century, their son had moved out of their home, and her sister, Catherine R. (Topley) Sponsler, had moved in. (See paragraph above for details.) Widowed by her husband in 1919 Permelia (Topley) Martin, died at the age of eighty in Westmont, Cambria County, Pennsylvania on 9 April 1924. Her remains were subsequently returned to Baltimore for interment at that city’s Druid Ridge Cemetery.

Following her marriage to Isaiah McCaskey, George Topley’s sister, Mary Ellen (Topley) McCaskey, initially settled with her husband in New Bloomfield, Perry County, Pennsylvania. She then welcomed the births of multiple children, including: Addie F. McCaskey (1865-1872), who was born on 21 October 1865, but died in Dauphin County at the age of seven, four days after Christmas in 1872; Ethel McCaskey (1874-1875), who was born on 13 January 1874, but died in Dauphin County at the age of nineteen months on 20 August 1875; and H. Wilson McCaskey (1878-1881), who was born on 5 June 1878, but died in Dauphin County on 5 March 1881, roughly three months before his third birthday. Preceded in death by her husband Isaiah McCaskey, who passed away in Dauphin County, on 6 September 1911, just shy of his eighty-second birthday, Mary Ellen (Topley) McCaskey died in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, at the age of seventy-nine, just two days after Christmas. Her remains were subsequently returned to Dauphin County for interment beside her husband and children at the Middletown Cemetery in Middletown, Dauphin County.

Meanwhile, George Topley’s younger brother and fellow tinsmith, William A. Topley, was hammering out a new life for himself in Lambertville, Hunterdon County, New Jersey in July 1870. By the end of that decade, he had met and married Ida Glendora Mulford in the city of Trenton in Mercer County on 3 July 1877. Roughly three years later, he and his wife, Ida, were residing in the city of Camden in Camden County, New Jersey, with their daughter, Elizabeth M. Topley (1878-1960), who had been born on 20 March 1878 and was known to family and friends as “Lizzie.” That year’s federal census enumerator noted that William Topley was still employed as a “tinman.” Also living with them was sixty-four-year-old Elisabeth Mulford.

Two more children soon followed: William Albert Topley (1881-1959), who was born in Camden, New Jersey on 13 June 1881 and later wed Anna Grouser (1895-1965); and Harry Wilton Topley (1890-1929), who was born in Trenton, Mercer County on 16 April 1890, later wed Louise Beck, became an automotive salesman, and resided with his family in Grosse Pointe Shores, Michigan.

Shortly after the turn of the century, George Topley’s brother, William A. Topley, Sr., was still employed as a tinsmith and was residing in the city of Trenton with his wife and their children, Elizabeth, who was employed as a telephone operator, William, who was employed as an electrician, and Harry, who was still attending school. Although their household makeup remained the same in Trenton in 1910, and family patriarch William was still hard at work as a tinsmith at a tin shop, his namesake, William A. Topley, Jr., was employed that year as a “wire worker” at a wire mill, while daughter Elizabeth was employed as a clerk by a wholesale grocer, and son Harry was employed as a clerk by an automobile company.

Ailing with heart disease in his final years, William A. Topley, Sr. survived his brother George by more than half of a century. Following his death in Trenton, New Jersey, on 13 June 1916, William was laid to rest at the Ewing Cemetery in Ewing, Mercer County.

Sources:

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Harry Wilton Topley (a son of William A. Topley and a nephew of George W. Topley), in U.S. World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Henry Wilson Sheibley” (obituary of the husband of George W. Topley’s youngest sister, Addie F. (Topley) Sheibley). New Bloomfield, Pennsylvania: The Perry County Democrat, 8 February 1922.

- Marten [sic, Martin], H. William and A. Permelia (a sister of George W. Topley); and Sponsler, Catherine R., in U.S. Census (Baltimore City, 10th Precinct, Baltimore County, Maryland, 1900). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Martin, William, Amelia [sic, Permelia (a sister of George W. Topley)], in U.S. Census (Baltimore County, First District, Maryland, 1870, 1880). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- McCaskey, Isaaih [sic, Isaiah], Mary E. and Carrie, in U.S. Census (New Bloomfield Post Office, Borough of Bloomfield, Perry County, 1860). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Mrs. Kate Sponsler” (obituary of Catherine R. (Topley) Sponsler, a sister of George W. Topley). Bloomfield, Pennsylvania: The Perry County Democrat, 28 January 1925.

- “Permelia Alinda Martin” (a sister of George W. Topley), in Death Certificates (file no.: 43639, registered no.: 8, date of death: 9 April 1924). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commowealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- “Return of a Death in Philadelphia: Physician’s Certificate” (Addie F. Sheibley, 25 January 1880). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Philadelphia City Archives.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1869.

- “Sheibley, Addie F.” (death notice of the youngest sister of George W. Topley). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Philadelphia Inquirer, 28 January 1880.

- Sheibley, H. Wilson (groom) and Topley, Addie F. (bride and the youngest sister of George W. Topley), in Marriage Records, 1868. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Trinity Reformed Church.

- Shibley [sic, Sheibley], Henry, Addie and Amelia; and Beal, Porter (store clerk), in U.S. Census (Philadelphia, Thirteenth Ward, Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, 1870). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Sponsler” (obituary of Catherine R. (Topley) Sponsler, a sister of George W. Topley). Baltimore, Maryland: The Baltimore Sun, 29 January 1925.

- Tapley [sic, Topley], George W., in U.S. Registers of Deaths of Volunteers (Petersburg, Virginia, June 1864). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Tapply [sic, Topley], William, Ida and Elisa; and Mulford, Elisabeth, in U.S. Census (Camden, Camden County, New Jersey, 1880). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Topley, Alexander, Susannah, Ann E., Catharine R., Mary E., George W., Lemuel, William, Familia [sic, Permelia], and Adda [sic, Addie], in U.S. Census (Borough of Bloomfield, Perry County, Pennsylvania, 1850). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Topley, George, in Civil War Muster Rolls (Company D, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry; and Company K, 2nd Pennsylvania Artillery). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Topley, George W., in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 (Company D, 2nd Pennsylvania Infantry; and Company K, 2nd Pennsylvania Artillery). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Topley, George W. and William, in U.S. Civil War Draft Registration Records (Cumberland and Perry Counties, Pennsylvania, 1863). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Topley, George Washington (infant baptized), Alexander and Susan (parents), in Birth and Baptismal Records (1836-1937). Landisburg, Pennsylvania: Presbyterian Church.

- Topley, George W. (deceased soldier) and Susan (mother), in U.S. Civil War Pension General Index Cards (mother’s pension application no.: 73696, filed on 20 December 1864). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Topley, Harry (son), George (father) and Ida (mother), in Birth Records (Trenton, Mercer County, New Jersey, 16 April 1890). Trenton, New Jersey: New Jersey State Archives.

- Topley, Lizzie M. (daughter), George (father) and Ida (mother), in Birth Records (New Jersey, 20 March 1878). Trenton, New Jersey: New Jersey State Archives.

- Topley, W. (the younger brother of George W. Topley), and John K. Zeigler (hotel keeper), et. al., in U.S. Census (Lambertville, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, 1870). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Topley, Wm. A. (son), George (father) and Ida (mother), in Birth Records (Camden, Camden County, New Jersey, 13 June 1881). Trenton, New Jersey: New Jersey State Archives.

- Topley, William A. (the younger brother of George W. Topley), Ida, Elizabeth, William (son), and Harry, in U.S. Census (Trenton, Mercer County, New Jersey, 1900, 1910). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Toply [sic, Topley], George W., in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 (Company D, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry; and Company K, 2nd Pennsylvania Artillery). Harrisburg, Pennylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Toply [sic, Topley], George W., in U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms (exhumation and transfer from the Avery Farm near Petersburg, Virginia to the Poplar Grove National Cemetery in Petersburg, Virginia). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Ward, George Washington. History of the Second Pennsylvania Veteran Heavy Artillery, (112th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers), from 1861 to 1866, Including the Provisional Second Penn’a Heavy Artillery. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: George W. Ward, Printer, 1904.

- “Will: Susannah Topley of Bloomfield Borough,” in Wills and Probate Records (Bloomfield Borough, Perry County, Pennsylvania, 1865). Perry County, Pennsylvania: Clerk of the Orphans’ Court.

- William A. Topley (the younger brother of George W. Topley and bride groom) and Ida Glendora Mulford (bride), in Marriage Records (Trenton, Mercer County, New Jersey, 3 July 1877). Trenton, New Jersey: New Jersey State Archives.

- “William A. Topley, Sr.” (obituary of the younger brother of George W. Topley). Trenton, New Jersey: Trenton Evening Times, 14 June 1916.

- William Albert Topley (a son of William A. Topley and a nephew of George W. Topley), in U.S. World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Wood, Robert. “Tinware of the 18th and 19th Centuries.” Green Lane, Pennsylvania: The Goschenhoppen Historians, retrieved online 24 April 2025.

You must be logged in to post a comment.