Soldiers and Sailors Monument, New Bloomfield, Perry County, Pennsylvania, circa early 1900s (public domain).

Ephraim Clouser (1837-1899) was as much of a casualty as any of his fellow soldiers who were killed in action during the American Civil War, but he was never truly accorded the respect that those other men are still given more than one hundred and fifty years after they died in hospitals or on battlefields far from loved ones. Shamed publicly by members of his community and branded as “a dangerous character” by one of the most successful newspaper’s in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s capital city, he was, in truth, most likely just a hard-working, tender-hearted person who simply had the terrible misfortune to develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) before being taken advantage of in his later years by a court-appointed “guardian” who had been placed in charge of managing his financial affairs.

Formative Years

Born on 14 October 1837 in Perry County, Pennsylvania, Ephraim Clouser was a son of William Clouser (1814-1856) and Elizabeth (Reisdorf) Clouser (born in 1814).

In 1850, he resided in Centre Township, Perry County with his parents and siblings: Mary J. Clouser, who was born circa 1841; William H. Clouser, who was born circa 1842; Sarah E. Clouser, who was born circa 1844; and Elizabeth Clouser, who was born circa 1848. His father supported their family on the wages of a carpenter and owned real estate that was valued at seven hundred dollars by that year’s federal census enumerator.

Just six years later, however, the Clouser children’s security was shattered by the untimely death of their father. Still in his early forties when he passed away in 1856, William Clouser was laid to rest at the Bloomfield Cemetery in New Bloomfield, Perry County.

Adding to their concerns for the future, their nation began a shocking descent into the madness of disunion and civil war with the secession of South Carolina from the United States on 20 December 1860.

* Note: While Ephraim Clouser was hard at work as an elementary school student in Centre Township, Perry County, Pennsylvania during the late 1840s, his first cousin, John Lewellyn Clouser, was just beginning his own life in Centre Township. Born in Perry County on 3 February 1847, John L. Clouser was a son of Pennsylvania natives David Clouser (1816-1898) and Agnes Ann (Gantt) Clouser (1818-1883), who was known to family and friends as “Nancy.” By 1850, John was also living in Centre Township with his parents and siblings, and would, like his first cousin Ephraim, later go on to serve in the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers during the American Civil War.

American Civil War — 15th Pennsylvania Volunteers

Excerpt from the images of the Battle of Falling Waters, Virginia. “Council of War” shows “Generals Williams, Cadwalader, Keim, Nagle, Wynkoop, and Colonels Thomas and Longnecker” strategizing on the eve of battle (Harper’s Weekly, 27 July 1861).

One of the earliest responders to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers to help defend the nation’s capital following the April 1861 fall of Fort Sumter to Confederate forces, Ephraim Clouser enrolled for military service and mustered in for duty as a private with Company B of the 15th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry on 23 April 1861 in Harrisburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania.

Following basic training there, the 15th Pennsylvania Infantry, a regiment with a renowned brass band, was transported to Camp Johnston near Lancaster, Pennsylvania on 9 May 1861. Subsequently ordered to Camp Patterson near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania on 3 June, the 15th Pennsylvania was next stationed at Camp Negley near Hagerstown, Maryland beginning 16 June. Marching briefly to Williamsport, Pennsylvania and back, the regiment was then stationed at Camp Porter beginning 21 June 1861.

On July 2 1861, Private Ephraim Clouser and his fellow 15th Pennsylvanians received their first taste of combat when they engaged in the Battle of Falling Waters, Virginia. During that confrontation with the enemy, more than thirty members of the regiment were captured. (Designated as prisoners of war while they were confined in Richmond, Virginia, those Pennsylvania POWs were subsequently shipped south to a Confederate prison camp in New Orleans, Louisiana.)

Meanwhile, on 3 July 1861, Private Ephraim Clouser and his regiment were heading for Martinsburg, Virginia. Stationed there as an occupying force until 15 July, they then moved on to Bunker Hill, where they were encamped for two days before receiving orders to march for Charlestown. By 26 July, Private Clouser and his fellow 15th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantrymen were back in Hagerstown, Maryland.

Subsequently ordered to defend Carlisle, Pennsylvania, they were stationed there until 7 August 1861. Having successfully completed their agreed-upon Three Months’ Service, Private Ephraim Clouser and his comrades were then honorably mustered out the following day.

American Civil War — 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers

On 20 August 1861, at the age of twenty-two, Ephraim Clouser re-upped for a three-year term of service, enrolling in Bloomfield, Perry County, Pennsylvania. He then mustered in at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg — this time on 31 August as a private with Company D of the newly-formed 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Following a brief training period in light infantry tactics, Private Ephraim Clouser and his company were sent by train with the 47th Pennsylvania to Washington, D.C. where they were stationed at “Camp Kalorama” on Kalorama Heights near Georgetown, about two miles from the White House, beginning 20 September. Two days later, C Company Musician Henry D. Wharton penned these words to his hometown newspaper, the Sunbury American:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a setting [sic, set] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposefully erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men that, on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so adapt [sic, wrapped] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on discovering they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.

Col. Good, who has command of our regiment, is an excellent man and a splendid soldier. He is a man of very few words, and is continually attending to his duties and the wants of the Regiment.

…. Our Regiment will now be put to hard work; such as drilling and the usual business of camp life, and the boys expect and hope for an occasional ‘pop’ at the enemy.

Chain Bridge across the Potomac above Georgetown looking toward Virginia, 1861 (The Illustrated London News, public domain).

Acclimated somewhat to their new life, the soldiers of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry finally became part of the Army of the United States when they were officially mustered into federal service on 24 September. Three days later, they were assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General Isaac Ingalls Stevens, which also included the 33rd, 49th and 79th New York regiments. By that afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were on the move again.

Ordered onward by Brigadier-General Silas Casey, the Mississippi rifle-armed 47th Pennsylvania infantrymen marched behind their Regimental Band until reaching Camp Lyon, Maryland on the Potomac River’s eastern shore. At 5 p.m., they joined the 46th Pennsylvania in moving double-quick (one hundred and sixty five steps per minute using thirty-three-inch steps) across the “Chain Bridge” marked on federal maps, and continued on for roughly another mile before being ordered to make camp.

The next morning, they broke camp and moved again. Marching toward Falls Church, Virginia, they arrived at Camp Advance around dusk. There, about two miles from the bridge they had crossed a day earlier, they re-pitched their tents in a deep ravine near a new federal fort under construction (Fort Ethan Allen). They had completed a roughly eight-mile trek, were situated close to the headquarters of Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith (also known as “Baldy”) and were now part of the massive U.S. Army of the Potomac (“Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Under Smith’s leadership, their regiment and brigade would help to defend the nation’s capital from the time of their arrival through late January when the men of the 47th Pennsylvania would be shipped south.

Once again, Company C Musician Henry Wharton recalled the regiment’s activities, noting, via his 29 September letter to the Sunbury American:

On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders.)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march the morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic, Lewinsville], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six tons of hay. A nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment….

The Big Chestnut Tree, Camp Griffin, Langley, Virginia, 1861 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Sometime during this phase of duty, as part of the 3rd Brigade, the 47th Pennsylvanians were moved to a site they initially christened “Camp Big Chestnut,” in reference to a large chestnut tree growing there. The site would eventually become known to them as “Camp Griffin,” and was located roughly ten miles from Washington, D.C.

On 11 October, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads. In a mid-October letter to his own family and friends, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin, the commanding officer of Company C, reported that Companies D, A, C, F, and I (the 47th Pennsylvania’s right wing) were ordered to picket duty after the regiment’s left-wing companies (B, E, G, H, and K) had been forced to return to camp by Confederate troops.

In his letter of 13 October, Musician Henry Wharton described the duties of the average 47th Pennsylvanian, as well as the regiment’s new home:

The location of our new camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic, chestnut] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets. Last night, however, they (the Rebels) calculated wide of their mark; some of the New York 33d boys were out on picket; some fourteen or fifteen shots were exchanged, when our side succeeded in bringing to the dust, (or rather mud,) an officer and two privates of the enemy’s mounted pickets. The officer was shot by a Lieutenant in Company H [?], of the 33d.

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually, but the hardest was on picket from last Thursday morning ’till Saturday morning – all the time four miles from camp, and both of the nights the rain poured in torrents, so much so that their clothes were completely saturated with the rain. They stood it nobly – not one complaining; but from the size of their haversacks on their return, it is no wonder that they were satisfied and are so eager to go again tomorrow. I heard one of them say ‘there was such nice cabbage, sweet and Irish potatoes, turnips, &c., out where their duty called them, and then there was a likelihood of a Rebel sheep or young porker advancing over our lines and then he could take take them as ‘contraband’ and have them for his own use.’ When they were out they saw about a dozen of the Rebel cavalry and would have had a bout with them, had it not been for … unlucky circumstance – one of the men caught the hammer of his rifle in the strap of his knapsack and caused his gun to fire; the Rebels heard the report and scampered in quick time….

On Friday morning, 22 October 1861, the 47th engaged in a divisional review, described by historian Lewis Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review that was monitored by the regiment’s founder and commanding officer, Colonel Tilghman H. Good — a formal inspection that was followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

As a reward — and in preparation for bigger things to come, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan obtained new Springfield rifles for every member of the 47th Pennsylvania.

1862

Ordered to move from their Virginia encampment back to Maryland, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862. Marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church, they were transported to Alexandria, where they boarded the steamship City of Richmond and sailed the Potomac River to the Washington Arsenal, where they disembarked and were re-equipped. Subsequently marched to the Soldiers’ Rest in Washington, D.C., they were fed and given the opportunity to relax there. The next afternoon, they were marched to the railroad station, where they hopped aboard a train from the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland.

Arriving around 10 p.m., they disembarked and were marched to a barracks at the United States Naval Academy, where they bedded down for the night. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January) loading their equipment and supplies onto the U.S.S. Oriental.

During the afternoon of 27 January, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers began boarding the Oriental, enlisted men first, and then, per the directive of Brigadier-General Brannan, they steamed away at 4 p.m. and headed for Florida, which, despite its secession from the United States remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of several key federal installations.

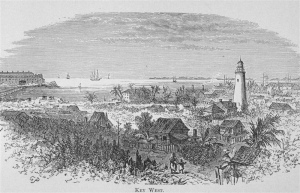

Lighthouse, Key West, Florida, early to mid-1800s (Florida for Tourists, Invalids, and, Settlers, George M. Barbour, 1881, public domain).

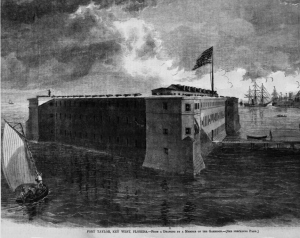

Arriving in Key West, Florida by early February 1862, the men of Company D and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers disembarked and were ordered to pitch their tents on the beach, where they rested and were subsequently directed to their respective quarters inside and outside of Fort Taylor. Assigned to garrison the fort, they drilled daily in infantry and artillery tactics, began strengthening the fortifications of this key federal installation and also began making infrastructure improvements to the city by felling trees and building new roads.

During the weekend of 14 February, the regiment introduced itself to area residents via a parade through the city’s streets. That Sunday, the 47th Pennsylvanians began mingling with locals at area church services.

Among the lighter moments, the regiment commemorated the birthday of President George Washington with a parade, a special ceremony involving the reading of Washington’s farewell address to the nation (first delivered in 1796), the firing of cannon at the fort, and a sack race and other games on 22 February. The festivities resumed two days later when the Regimental Band hosted an officers’ ball at which “all parties enjoyed themselves, for three o’clock of the morning sounded on their ears before any motion was made to move homewards,” according to Musician Henry Wharton. This was then followed by a concert by the regimental band on Wednesday evening, 26 February.

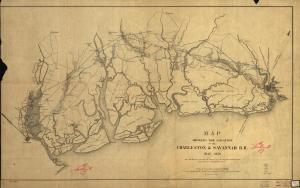

This 1856 map of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad shows the island of Hilton Head, South Carolina in relation to the towns of Beaufort and Pocotaligo (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain; click to enlarge).

Next ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina, from early June through July, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers camped near Fort Walker before relocating roughly thirty-five miles away in the Beaufort District in the U.S. Army’s Department of the South. Frequently assigned to hazardous picket duty north of their main camp, they faced an increased risk of enemy sniper fire. Despite this danger, though, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan” for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing,” according to historian Samuel P. Bates.

Detachments from the regiment were also assigned to the Expedition to Fenwick Island (9 July) and the Demonstration against Pocotaligo (10 July).

Capture of Saint John’s Bluff, Florida and a Confederate Steamer

Earthworks surrounding the Confederate battery atop Saint John’s Bluff along the Saint John’s River in Florida (J. H. Schell, 1862, public domain).

During a return expedition to Florida, beginning 30 September, the 47th Pennsylvania joined with the 1st Connecticut Battery, 7th Connecticut Infantry and part of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry in assaulting Confederate forces at their heavily protected camp at Saint John’s Bluff, overlooking the Saint John’s River. Trekking through roughly twenty-five miles of swampland and forests, after disembarking from their Union troop transports at Mayport Mills on 1 October, the 47th Pennsylvanians captured artillery and ammunition stores (on 3 October) that had been abandoned during the Union Navy’s bombardment of the bluff.

Men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies E and K were then led by Captain Charles H. Yard on a special mission; initially joining with other Union troops in the reconnaissance and capture of Jacksonville, Florida, they were subsequently ordered to sail up the Saint John’s River to seek out and capture any Confederate ships they found. Departing aboard the Darlington, a former Confederate steamer, with protection by the Union gunboat Hale, they traveled two hundred miles upriver, captured the Governor Milton, a Confederate steamer that was docked near Hawkinsville, and returned back down the river with both Union ships and their new Confederate prize without incident. (Identified as a thorn that needed to be plucked from the Union’s side, that steamer had been engaged in ferrying Confederate troops and supplies around the region.)

Integration of the Regiment

Meanwhile, back at its South Carolina base of operations, the 47th Pennsylvania was making history as it became an integrated regiment. On 5 and 15 October, the regiment added to its rosters several young Black men who had endured plantation enslavement near Beaufort and other areas of South Carolina, including Bristor Gethers, Abraham Jassum and Edward Jassum.

Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina

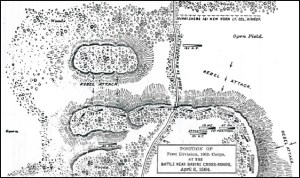

Highlighted version of the U.S. Army map of the Coosawhatchie-Pocotaligo Expedition, 22 October 1862 (public domain).

From 21-23 October 1862, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers joined with other Union troops in engaging heavily protected Confederate troops in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina, including at Frampton’s Plantation and the Pocotaligo Bridge, a key piece of Deep South infrastructure that senior Union military leaders felt should be eliminated.

Harried by snipers while en route to destroy the bridge, they met resistance from an entrenched, heavily fortified Confederate battery that opened fire on the Union troops as they entered an open cotton field.

Those headed toward higher ground at the Frampton Plantation fared no better as they encountered artillery and infantry fire from the surrounding forests. But the Union soldiers would not give in. Grappling with the Confederates where they found them, they pursued the Rebels for four miles as the Confederate Army retreated to the bridge. Once there, the 47th Pennsylvania relieved the 7th Connecticut.

Unfortunately, the enemy was just too well armed. After two hours of intense fighting in an attempt to take the ravine and bridge, the 47th Pennsylvanians were forced by depleted ammunition to withdraw to Mackay’s Point.

Losses for the 47th were significant. Two officers and eighteen enlisted men died; two officers and an additional one hundred and fourteen enlisted men were wounded.

Badly battered when they returned to Hilton Head on 23 October, a number of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were subsequently selected to serve as the funeral honor guard for General Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel, the commander of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps and Department of the South who had succumbed to yellow fever on 30 October. The Mountains of Mitchel, a part of Mars’ South Pole discovered by Mitchel in 1846 while working as a University of Cincinnati astronomer, and Mitchelville, the first Freedmen’s town created after the Civil War, were both later named for him. Men from the 47th Pennsylvania were given the honor of firing the salute over his grave.

Fort Jefferson and its wharf areas, Dry Tortugas, Florida (Harper’s Weekly, 23 February 1861, public domain).

Having been ordered back to Key West on 15 November 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers would spend much of 1863 guarding federal installations in Florida as part of the 10th Corps, Department of the South. Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I would once again garrison Fort Taylor in Key West, while the men of Companies D, F, H, and K would garrison Fort Jefferson, the Union’s remote outpost in the Dry Tortugas off the southern coast of Florida.

After packing their belongings at their Beaufort, South Carolina encampment and loading their equipment onto the U.S. Steamer Cosmopolitan, the officers and enlisted members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry sailed toward the mouth of the Broad River on 15 December 1862, and anchored briefly at Port Royal Harbor in order to allow the regiment’s medical director, Elisha W. Baily, M.D., and members of the regiment who had recuperated enough from their Pocotaligo-related battle injuries at the Union’s general hospital at Hilton Head, to rejoin the regiment.

At 5 p.m. that same evening, the regiment sailed for Florida, during what was described by several members of the regiment as a treacherous and nerve-wracking voyage. According to Schmidt, the ship’s captain “steered a course along the coast of Florida for most of the voyage,” which made the voyage more precarious “because of all the reefs.” On 16 December, “the second night, the ship was jarred as it ran aground on one during a storm, but broke free, and finally steered a course further from shore, out in the Gulf Stream.”

In a letter penned to the Sunbury American on 21 December, Musician Henry Wharton provided the following details about the regiment’s trip:

On the passage down, we ran along almost the whole coast of Florida. Rather all dangerous ground, and the reefs are no playthings. We we jarred considerably by running on one, and not liking the sensation our course was altered for the Gulf Stream. We had heavy sea all the time. I had often heard of ‘waves as big as a house,’ and thought it was a sailors yarn, but I have seen ’em and am perfectly satisfied; so now, not having a nautical turn of mind, I prefer our movements being done on terra firma, and leave old neptune to those who have more desire for his better acquaintance. A nearer chance of a shipwreck never took place than ours, and it was only through Providence that we were saved. The Cosmopolitan is a good riverboat, but to send her to sea, loadened [sic, loaded] with U.S. troops is a shame, and looks as though those in authority wish to get clear of soldiers in another way than that of battle. There was some sea sickness on our passage; several of the boys ‘casting up their accounts’ on the wrong side of the ledger.

According to Corporal George Nichols of Company E, “When we got to Key West the Steamer had Six foot of water in her hole [sic, hold]. Waves Mountain High and nothing but an old river Steamer. With Eleven hundred Men on I looked for her to go to the Bottom Every Minute.”

Although the Cosmopolitan arrived at the Key West Harbor on Thursday, 18 December, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers did not set foot on Florida soil until noon the next day. The men from Companies C and I were immediately marched to Fort Taylor, where they were placed under the command of Major William Gausler, the regiment’s third-in-command. The men from Companies B and E were assigned to the older barracks that had been erected by the United States Army, and were placed under the command of B Company Captain Emanuel P. Rhoads, while the men from Companies A and G were placed under the command of A Company Captain Richard Graeffe, and stationed at newer facilities known as the “Lighthouse Barracks,” which were located on “Lighthouse Key.”

On Saturday, 21 December, Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, the regiment’s second-in-command, sailed away aboard the Cosmopolitan with the men from Companies D, F, H, and K, and headed south to Fort Jefferson, roughly seventy miles off the coast of Florida (in the Gulf of Mexico) to assume garrison duties there. According to Musician Henry Wharton:

We landed here [Fort Taylor] on last Thursday at noon, and immediately marched to quarters. Company I. and C., in Fort Taylor, Company E. and B. in the old Barracks, and A. and G. in the new Barracks. Lieut. Col. Alexander, with the other four companies proceeded to Tortugas, Col. Good having command of all the forces in and around Key West. Our regiment relieved the 90th Regiment N. Y. S. Vols. Col. Joseph Morgan, who will proceed to Hilton Head to report to the General commanding. His actions have been severely criticized by the people, but, as it is in bad taste to say anything against ones [sic, one’s] superiors, I merely mention, judging from the expression of the citizens, they were very glad of the return of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers….

Key West has improved very little since we left last June, but there is one improvement for which the 90th New York deserve a great deal of praise, and that is the beautifying of the ‘home’ of dec’d soldiers. A neat and strong wall of stone encloses the yard, the ground is laid off in squares, all the graves are flat and are nicely put in proper shape by boards eight or ten inches high on the end sides, covered with white sand, while a head and foot board, with the full name, company and regiment, marks the last resting place of the patriot who sacrificed himself for his country….

1863

Fort Jefferson’s moat and wall, circa 1934, Dry Tortugas, Florida (C. E. Peterson, U.S. Library of Congress; public domain).

Although water quality was a challenge for members of the regiment at both of their duty stations in Florida throughout 1863, it was particularly problematic for the 47th Pennsylvanians who were stationed at Fort Jefferson. According to Schmidt:

‘Fresh’ water was provided by channeling the rains from the city’s barbette through channels in the interior walls, to filter trays filled with sand; and finally to the 114 cisterns located under the fort which held, 1,231,000 gallons of water. The cisterns were accessible in each of the first level cells or rooms through a ‘trap hole’ in the floor covered by a temporary wooden cover…. Considerable dirt must have found its way into these access points and was responsible for some of the problems resulting in the water’s impurity…. The fort began to settle and the asphalt covering on the outer walls began to deteriorate and allow the sea water (polluted by debris in the moat) to penetrate the system…. Two steam condensers were available … and distilled 7000 gallons of tepid water per day for a separate system of reservoirs located in the northern section of the parade ground near the officers [sic, officers’] quarters. No provisions were made to use any of this water for personal hygiene of the [planned 1,500-soldier garrison force]….

As a result, the soldiers stationed there washed themselves and their clothes, using saltwater from the ocean. As if that weren’t difficult enough, “toilet facilities were located outside of the fort,” according to Schmidt:

At least one location was near the wharf and sallyport, and another was reached through a door-sized hole in a gunport and a walk across the moat on planks at the northwest wall…. These toilets were flushed twice each day by the actions of the tides, a procedure that did not work very well and contributed to the spread of disease. It was intended that the tidal flush should move the wastes into the moat, and from there, by similar tidal action, into the sea. But since the moat surrounding the fort was used clandestinely by the troops to dispose of litter and other wastes … it was a continuous problem for Col. Alexander and his surgeon.

Second-tier casemates, lighthouse keeper’s house, sallyport, and lean-to structure, Fort Jefferson, Dry Tortugas, Florida, late 1860s (U.S. National Park Service and National Archives, public domain).

As for daily operations in the Dry Tortugas, there was a fort post office and the “interior parade grounds, with numerous trees and shrubs in evidence, contained officers’ quarters, [a] magazine, kitchens and out houses,” per Schmidt, as well as “a ‘hot shot oven’ which was completed in 1863 and used to heat shot before firing.”

Most quarters for the garrison … were established in wooden sheds and tents inside the parade [grounds] or inside the walls of the fort in second-tier gun rooms of ‘East’ front no. 2, and adjacent bastions … with prisoners housed in isolated sections of the first and second tiers of the southeast, or no. 3 front, and bastions C and D, located in the general area of the sallyport. The bakery was located in the lower tier of the northwest bastion ‘F’, located near the central kitchen….

Additional Duties: Diminishing Florida’s Role as the “Supplier of the Confederacy”

On top of the strategic role played by the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers in preventing foreign powers from assisting the Confederate Army and Navy in gaining control over federal forts in the Deep South, the regiment was also called upon to play an ongoing role in weakening Florida’s abilities to supply and transport food and troops throughout areas held by the Confederate States of America.

Prior to intervention by the Union Army and Navy, the owners of plantations and livestock ranches, as well as the operators of small, family farms across Florida, had been able to consistently furnish beef and pork, fish, fruits, and vegetables to Confederate troops stationed throughout the Deep South during the first year of the American Civil War. Large herds of cattle were raised near Fort Myers, for example, while orchard owners in the Saint John’s River area were actively engaged in cultivating sizeable orange groves (while other types of citrus trees were found growing throughout more rural areas of the state).

Florida was also a major producer of salt, which was used as a preservative for food. As a result, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and other Union troops across Florida were ordered to capture or destroy salt manufacturing facilities in order to further curtail the enemy’s access to food.

But they were undertaking all of these duties in conditions that were far more challenging than any they had previously faced (and that were far more challenging than what many other Union troops were facing up north). The weather was frequently hot and humid as spring turned to summer, mosquitos and other insects were an ever-present annoyance (and serious threat when they were carrying tropical diseases) and there were also scorpions and snakes that put the men’s health at further risk.

As part of their efforts to ensure the efficacy of their ongoing operations, regimental officers periodically tweaked the assignments of individual companies during that year of garrison duty. One of those changes occurred on 16 May 1863 when D Company Captain Henry D. Woodruff and his men marched to the wharf at Fort Jefferson and climbed aboard yet another ship — this time for their return to Fort Taylor in Key West, where they resumed garrison duties under the command of Colonel Tilghman H. Good.

Four days later, enlisted members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were finally given eight months’ worth of their back pay — a significant percentage of which was quickly sent home to family members who had been struggling to make ends meet.

Despite all of these hardships, when members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were offered the opportunity to re-enlist during the fall of 1863, more than half of the regiment’s personnel did so without hesitation. Among those choosing to re-up for an additional tour of duty was Private Ephraim Clouser, who re-enlisted as a private with the same regiment and company at Fort Taylor in Key West on 10 October 1863.

1864

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers experienced yet another significant change when members of the regiment were ordered to expand the Union’s reach by sending part of the regiment north to retake possession of Fort Myers, a federal installation that had been abandoned in 1858, following the federal government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. In response, A Company Captain Richard Graeffe and a group of soldiers from Company A traveled north, captured the fort and began conducting cattle raids to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across Florida. They subsequently turned the fort not only into their base of operations, but into a shelter for pro-union supporters, escaped slaves, Confederate deserters, and others fleeing Rebel troops.

Red River Campaign

Map of key 1864 Red River Campaign locations, showing the battle sites of Sabine Cross Roads, Pleasant Hill and Mansura in relation to the Union’s occupation sites at Alexandria, Grand Ecore, Morganza, and New Orleans (excerpt from Dickinson College/U.S. Library of Congress map, public domain; click to enlarge).

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had begun preparing for the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer, the Charles Thomas, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by the men from Companies E, F, G, and H.

Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost-fully-reunited regiment moved by train to Brashear City (now Morgan City, Louisiana) before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps (XIX Corps), and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks. (Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the soldiers from Company A were assigned to detached duty while awaiting transport that enabled them to reconnect with their regiment at Alexandria, Louisiana on 9 April).

From 14-26 March, the 47th passed through New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington while en route to Alexandria and Natchitoches. Often short on food and water, the regiment encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day, marching until mid-afternoon.

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division, sixty members of the 47th were cut down on 8 April during the volley of fire unleashed during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads. The fighting waned only when darkness fell. Exhausted, those who were uninjured collapsed between the bodies of the gravely wounded and dead. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate Major-General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner and son of Zachary Taylor, former president of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault during what has since become known as the Battle of Pleasant Hill.

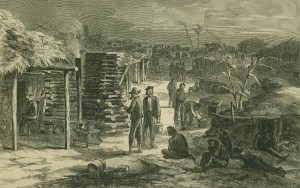

This 1865 illustration depicted life at Camp Ford, the largest Confederate prison camp west of the Mississippi River (Harper’s Weekly, 4 March 1865, public domain).

Once again, casualties were severe. And this time, the roster included the names of a number of men from Company D, including Private Ephraim Clouser, who was listed among the wounded and missing. Shot in the right knee by a Confederate rifle, he and multiple other 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantrymen had been captured by Rebel troops and marched roughly one hundred and twenty-five miles southwest to Camp Ford, the largest Confederate States prison camp west of the Mississippi River.

Located in Smith County, Texas, near the town of Tyler, that prisoner of war camp has been portrayed by some historians as far less dangerous of a place of captivity for Union soldiers than Andersonville and other Confederate prisons because its living conditions were reportedly “better” than the conditions found at those infamous POW camps — theoretically because the number of POWs held at Camp Ford was smaller and, therefore, “more easily cared for.” But as Camp Ford’s POW population skyrocketed in 1864, fueled by the capture of thousands of Union soldiers during multiple Red River Campaign battles, those living conditions quickly deteriorated.

As food, safe drinking water and adequate shelter became increasingly scarce, more and more of the Union soldiers confined there grew weak from starvation, fell ill and died due to the spread of typhoid and other infectious diseases, as well as the cases of dysentery and chronic diarrhea that were caused by the unsanitary placement of outdoor latrines near the camp’s water source.

On 12 June 1864, Private Samuel Kern, a D Company comrade of Private Clouser who had also been captured at Pleasant Hill, became one of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers who died at Camp Ford. Buried somewhere on the camp’s grounds, his precise final resting place remains unknown.

Four days later, Private Ephraim Clouser was reportedly one of a group of Union POWs who were being paroled at Red River Landing, Louisiana (on 16 June 1864, as part of a prisoner exchange agreement between the armies of United States and Confederate States). But that report turned out to be a false one.

Private Clouser was actually being held back from release by his Camp Ford captors — for a reason which has yet to be identified by researchers. Forced to languish there as a POW for an additional five months, during which time he was at increasing risk of starvation, physical and mental illness, or death, he was finally released to the Union Army on 25 November 1864.

*Note: The total number of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers captured by Confederate troops during the Red River Campaign was seventeen, according to Camp Ford prison rosters that are maintained by the Smith County Historical Society in Tyler, Texas. In addition to the aforementioned Samuel Kern of Company D, that list included the following members of D Company: Sergeant James Crownover, who had been shot in the right shoulder during the Battle of Pleasant Hill; Private Charles Brown, who was a bugler, according to his military records; Private Charles Buss (altername surname spelling: “Bress”); Private James Downs; Corporal John Garber Miller; and Private William J. Smith.

Held as prisoners of war (POWs) at Camp Ford, Bress, Brown, Downs, Miller, and Smith were released from captivity on 22 July 1864; Crownover was released on 25 November 1864 (the same day as Private Ephraim Clouser). While held as a POW, Crownover had been commissioned, but not mustered as, a second lieutenant on 31 August 1864, because regimental leaders hoped that his status as a higher-ranking officer might prompt his Confederate captors to treat him more leniently.

Unidentified Union soldiers in a ward of the U.S. Army General Hospital in Penn Park, York, Pennsylvania (circa 1864, public domain).

Placed on the sick rolls of the Army of the United States following his release from captivity, Private Ephraim Clouser appears to have been dropped from the muster rolls of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry for the remainder of the American Civil War.

Although the precise details of what happened to Private Clouser remain unclear, researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story have been able to determine that, following his release from Camp Ford, he was hospitalized at the Union Army’s Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, Missouri before being transferred to a Union Army hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio for more advanced care. From there, he was sent home to Pennsylvania to convalesce at the Union Army’s general hospital in York, Pennsylvania.

Clearly, Private Clouser’s battle wound, alone, had been serious enough to warrant a sustained period of medical treatment by a series of Union Army physicians. It may, in fact, have caused so much damage to his body that he was in terrible pain that required those Union physicians to prescribe opioids. According to the editors of Ballistic Trauma: A Practical Guide, “There are three mechanisms whereby a projectile can cause tissue injury”:

1. In a low-energy transfer wound, the projectile crushes and lacerates tissue along the track of the projectile, causing a permanent cavity. In addition, bullet and bone fragments can act as secondary missiles, increasing the volume of tissue crushed.

2. In a high-energy transfer wound, the projectile may impel the walls of the wound track radially outwards, causing a temporary cavity lasting 5 to 10 milliseconds before its collapse in addition to the permanent mechanical disruption produced….

3. In wounds where the firearm’s muzzle is in contact with the skin at the time of firing, tissues are forced aside by the gases expelled from the barrel of the fire, causing a localized blast injury.

And being imprisoned at an enemy POW camp, with little to no access to medical care — let alone access to the highest quality medical care available at large Union Army hospitals while trying to heal from that wound — likely made Private Clouser’s injury difficult to treat, even when he was finally being given the standard of care he needed.

Honorably discharged sometime after his convalescence at the Union hospital in York, Pennsylvania, his exact muster out date remains unclear.

Return to Civilian Life

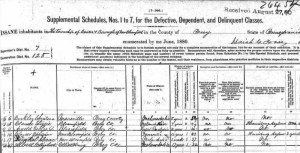

Entries of Ephraim and Lizzie Clouser, U.S. Census, Special Schedules: Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent Classes, Perry County, Pennsylvania, 1880 (U.S. National Archives and Records Administation, public domain; click to enlarge).

Sadly, the return home for Ephraim Clouser did not offer the peace he expected. Like many of his fellow American Civil War veterans, he suffered from mental health issues, which worsened over time. On 22 January 1866, he filed for an invalid’s pension through the U.S. Civil War Pension system, which was subsequently approved by the federal government. Further illustrating the depth of his suffering, the 1880 supplemental census of “Defective, Dependent, anhd Delinquent Classes” noted that he had already begun showing signs of “dementia” as early as 1868.

In reality, it is more likely that, having been a POW for so long, he may have actually developed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) — or “Soldier’s Heart,” as it was known during the Civil War.

* Note: We now know, thanks to decades of mental health research, that PTSD is an illness that can strike anyone at any time and can severely affect normal human functioning for many years after its symptoms first begin. Those who suffer from PTSD may experience anxiety, depression, difficulty maintaining work or social relationships, drug and/or alcohol abuse, eating disorders, and/or suicidal tendencies because this illness’s symptoms (hypervigilance to, and avoidance of, anyone or anything that might cause flashbacks, hallucinations, nightmares, or other intrusive memories about the germinative incident; an exaggerated startle response and difficulty concentrating; dyspnea/shortness of breath; effort fatigue; feelings of guilt, hopelessness, or shame; emotional or physical numbing and a flat affect; irritability or anger; heart palpitations; sleep disturbance or insomnia; sweating, etc.) take a terrible toll on the body, as well as the mind.

“Soldiers’ Heart” was researched and written about in the late 1860s and early 1870s by Jacob Mendes da Costa, M.D., a graduate of Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College who had served as a physician at Turner’s Lane Hospital in Philadelphia during the Civil War. He described what he was witnessing in his patients as an anxiety disorder linked to heart disease.

Why Ephraim Clouser may have developed Soldiers’ Heart/PTSD or another form of mental illness, when friends and neighbors of his did not, is still an unsolved mystery, but the origins of his condition and later difficulties in life can certainly be traced back to a war that left deep emotional scars on many of its participants because of the ways in which it was waged. It was a war that was “concentrated and personal, featuring large-scale battles in which bullets … caused over 90 percent of the carnage,” according to the late journalist Tony Horwitz.

Most troops fought on foot, marching in tight formation and firing at relatively close range, as they had in Napoleonic times. But by the 1860s, they wielded newly accurate and deadly rifles, as well as improved cannons. As a result, units were often cut down en masse, showering survivors with the blood, brains and body parts of their comrades.

Many soldiers regarded the aftermath of battle as even more horrific, describing landscapes so body-strewn that one could cross them without touching the ground….

Wounded men who survived combat were subject to pre-modern medicine, including tens of thousands of amputations with unsterilized instruments…. Opiates were widely available and generously dispensed for pain and other ills, causing another problem: drug addiction.

Though geographically less distant from home than soldiers in foreign wars, most Civil War servicemen were farm boys, in their teens or early 20s, who had rarely if ever traveled far from family and familiar surrounds. Enlistments typically lasted three years….

These conditions contributed to what Civil War doctors called ‘nostalgia,’ a centuries-old term for despair and homesickness so severe that soldiers became listless and emaciated and sometimes died. Military and medical officials recognized nostalgia as a serious ‘camp disease,’ but generally blamed it on ‘feeble will,’ ‘moral turpitude’ and inactivity in camp. Few sufferers were discharged or granted furloughs, and the recommended treatment was drilling and shaming of ‘nostalgic’ soldiers….

Consider the known facts about Ephraim Clouser. Wounded during the bloody Battle of Pleasant Hill — in a state that was more than thirteen hundred miles away from his hometown and was totally unfamiliar to him, he was then captured by Confederate soldiers during that same battle. Dragged off by those enemy troops to a prisoner of war camp that was located in an even more unfamiliar state that was even farther away from home (roughly sixteen hundred miles from Pennsylvania), he was still wounded as he was being force marched or transported, and likely received minimal to no medical care (and quite possibly with little to no anesthesia prior to being moved to that prison camp). He also likely was not given not much, if any, medical care after he arrived there.

Compounding his pain and suffering, he was taken to a prison where he was starved, exposed to extremes of heat and cold (due to a lack of adequate shelter), exposed to infectious diseases that were killing men all around him, and likely made sick himself by dysentery and chronic diarrhea caused by the lack of safe drinking water and unsanitary camp conditions that he was forced to endure.

And just when he thought he saw a spark of hope — the promise of his release during a June 1864 prisoner exchange — that spark was cruelly snuffed out when his captors failed to honor the release that had been negotiated and, instead, continued to keep him confined as a POW in the dismal and dangerous conditions at Camp Ford.

Combined with the knowledge that, even if he could escape somehow, he was so far from home, in such unfamiliar territory, that he would likely either be recaptured and punished severely, or that he would die during any attempt to get back to his regiment, how could his ordeal not have harmed his mind to some degree?

A Shattered Soul

Postcard depiction of the Pennsylvania State Lunatic Asylum, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, circa late 1800s (public domain).

Multiple newspapers that were published across Pennsylvania during the 1890s make clear just how serious Ephraim Clouser’s post-war condition was. On 22 September 1898, editors of the Harrisburg Telegraph noted that:

Ephraim Clouser, of Centre township, has been jailed as a dangerous character. A commission will look into his sanity.

Two years prior to that, the 18 February 1896 editions of The York Daily and the Altoona Tribune had reported on his increasing deterioration, and had also documented the heartbreaking news that one unkind and unethical man had taken advantage of Ephraim:

NEW BLOOMFIELD, Pa., February 17.- In the Perry county court, tonight, Judge Lyons committed William A. Sponsler, formerly president of the wrecked Perry County bank, to prison for contempt. Sponsler was the committee for Ephraim Clouser, an insane veteran, and collected over $3,000 of Clouser’s money, for which he failed to account. Sponsor was committed to prison until he would purge himself of this contempt.

The Altoona Tribune added the following details in its 19 February 1896 edition:

William A. Sponsler, for many years a leading attorney at the Perry County bar and president of the defunct Perry County bank, was remanded to jail by Judge Lyons at New Bloomfield on Monday evening for contempt of court, and almost immediately was taken into custody by the Sheriff of Perry county and lodged behind bars. Sponsler’s contempt arises from the misappropriation of money to the amount of $3,100 belonging to Ephraim Clouser, a wounded veteran of the late war. Clouser years ago was declared a lunatic and W. A. Sponsler was appointed by the court a committee to conduct his affairs. Sponsler became insolvent and was unable to pay this and a number of other claims of like character. A rule of court was asked for and granted ordering him to pay the claim. The rule was made answerable on several dates, but the final action was taken Monday evening. The order was imprisonment in the Perry county jail until the prisoner shall have been purged of the contempt – [by repayment]of the money.

Mr. Sponsler is about 70 years of age and was one of the Perry county nominees for president judge in the last contest for that honor in the Perry-Juniata district, being defeated by Judge Lyons, of Juniata. He was the republican candidate for congress at one time in the old York-Cumberland-Perry district, being defeated by Hon. John A. Magee, of the Perry County Democrat.

The Times of Philadelphia provided its own take on the situation on 21 February 1896:

William A. Sponsler, one of the oldest and long one of the most successful members of the New Bloomfield bar, has been committed to prison by Judge Lyons for contempt of court for failing, as committee, to pay to Ephraim Clouser the sum of $3,189.61, of trust funds as ordered by the Court on the 23d of November last. Mr. Sponsler was the senior member of the banking firm of Sponsler, Junkin & Co., and along with ex-Judge Junkin was convicted of technical embezzlement for receiving deposits when they knew that their banking house was insolvent. They were sentenced to prison for one year, but the Supreme Court admitted them to bail pending the hearing of the case, and reversed the verdict of conviction. Since then no new criminal prosecutions have been instituted. Mr. Sponsler being long a prominent and highly-respected member of the bar, had numerous trust funds in his hands, and among them the Clouser fund of over $3,000, that was doubtless lost in the broken bank. The Court having ordered the payment of the trust fund, the failure on the part of Sponsler to make the payment constituted a contempt of court, and he can be relieved of imprisonment only by the payment of the money.

Today, we would use the phrase “abuse of an adult with a physical or mental disability” to define the sickening, unbridled greed of William Sponsler. The amount that he stole from Ephraim Clouser’s soldiers’ pension would equal more than one hundred and ten thousand U.S. dollars in 2025, and was a large enough theft of critically needed funds that it clearly hastened Ephraim Clouser’s decline and death.

* Note: There were times when Ephraim Clouser was deemed well enough to return to his community, but his status, even during those lucid moments, was clearly viewed by those around him as precarious. In June 1880, for example, he was employed as a blacksmith in the Borough of New Bloomfield, where he also resided as a boarder at the hotel operated by George Ensminger; however, that year’s federal census enumerator made a point of documenting that Ephraim continued to be unwell. (The enumerator did so by checking boxes on that year’s census sheet for the categories of “Insane” and “Maimed, Crippled, Bedridden, or otherwise disabled” on the same line where Ephraim’s name was listed.)

Failing Health, Death and Interment

Harrisburg State Hospital (formerly known as the Pennsylvania State Lunatic Asylum), Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, circa 1890s (public domain).

On 13 January 1899, the Harrisburg Telegraph reported that “Ephraim Clouser, of Centre township, Perry County, [was] seriously ill in this city with heart disease and dropsy.” Three months later, the 16 March 1899 edition of that same newspaper reported on Ephraim Clouser’s funeral:

Funeral services were held in New Bloomfield Tuesday evening over the body of the late Ephraim Clouser, a war veteran, who died at the State Lunatic Hospital the other day from heart disease and dropsy, aged about 58 years. He was a native of Perry County and during the war was both wounded and captured. He was unmarried and leaves a considerable estate.

A long-time inmate at the Pennsylvania State Lunatic Asylum in Harrisburg (later known as the Harrisburg State Hospital), Ephraim Clouser passed away there, at the age of sixty-one, on 11 March 1899. His remains were returned to his community, where he was interred at the Bloomfield Cemetery in New Bloomfield, Perry County, Pennsylvania. The Harrisburg Daily Independent reported this news in its 18 March 1899 as follows:

The remains of Ephraim Clouser, who died at the insane asylum at Harrisburg, on Monday, were brought to Newport by express Tuesday morning and taken to his late home in Centre township for burial.

His wounded Soldier’s Heart now at rest, his war was finally over.

Sources:

- “A Perry County Sensation.” Altoona, Pennsylvania: Altoona Tribune, 18 February 1896.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Clouser, Ephraim, in, Civil War Muster Rolls (Company D, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Clouser, Ephraim, in, Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 (Company D, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Clouser, Ephraim, in Records of Burial Places of Veterans (New Bloomfield Cemetery, New Bloomfield, Pennsylvania; date of death: 11 March 1899). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Clouser, Ephraim, in U.S. Census (Special Schedule: Surviving Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, and Widows, etc., Centre Township, Perry County, Pennsylvania, 1890). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Clouser, Ephraim, in U.S. Civil War Pension General Index Cards (pension type: invalid, application no.: 100598, certificate no.: 72734, filed on 22 June 1866). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Clouser, Ephraim, Lizzie and Jacob, in U.S. Census (Supplemental Schedules, Nos. 1 to 7, for the Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent Classes: Insane Inhabitants in the Township of Centre and Borough of New Bloomfield, Perry County, Pennsylvania, 1880). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Clouser, William (father), Elizabeth (mother), Ephraim, Mary J., William H., Sarah E., and Elizabeth (daughter), in U.S. Census (Centre Township, Perry County, Pennsylvania, 1850). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- da Costa, Jacob Mendez. “Observations on the diseases of the heart noticed among soldiers, particularly the organic diseases,” in Contributions relating to the Causation and Prevention of Disease, and to Camp Diseases; together with a Report of the Diseases, etc., Among the Prisoners at Andersonville, GA.” New York: United States Sanitary Commission and Hurd and Houghton, 1867.

- “Deaths and Funerals: Ephraim Clouser.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Harrisburg Telegraph, 16 March 1899.

- Ensminger, George (hotel keeper), Villie (his wife and the hotel’s cook, Wilson M. (son), Minnie M. (daughter), and “Baby” (son); four hotel servants; and six boarders, including Ephraim Clouser), in U.S. Census (Borough of New Bloomfield, Perry County, Pennsylvania, 1880). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Florida’s Role in the Civil War,” in Florida Memory. Tallahassee, Florida: State Archives of Florida.

- Hain, Harry Harrison. History of Perry County, Pennsylvania. Including Descriptions of Indians and Pioneer Life from the Time of Earliest Settlement. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Hain-Moore Company, 1922.

- Horwitz, Tony. “Did Civil War Soldiers Have PTSD?”, in Smithsonian Magazine, January 2015. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

- Jones, Jonathan S. “Opium Slavery: Civil War Veterans and Opiate Addiction,” in The Journal of the Civil War Era, vol. 10, no. 2, June 2020, pp. 185-212. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press.

- “Lawyer Sponsler Committed.” York, Pennsylvania: The York Daily Record, 18 February 1896.

- Mahoney, Peter F., James Ryan, et. al. Ballistic Trauma: A Practical Guide, Second Edition, pp. 31-66, 91-121, 168-179, 356-395, 445-464, 535-540, 596-605. London, England: Springer-Verlag London Limited, 2005.

- “Newport: Special Correspondence” (notice documenting Ephraim Clouser’s confinement and later death at the asylum in Harrisburg). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Harrisburg Daily Independent, 18 March 1899.

- Notice of Ephraim Clouser’s Illness. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Harrisburg Telegraph, 13 January 1899.

- “Pennsylvania Notes” (update regarding the embezzlement charges against William A. Sponsler, the court-appointed guardian for Ephraim Clouser). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Times, 21 February 1896.

- Pollard, Harvey, Chittari Shivakumar, et. al. “‘Soldier’s Heart’: A Genetic Basis for Elevated Cardiovascular Disease Risk Associated with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder,” in Frontiers in Neuromolecular Science, 23 September 2016. Switzerland: Frontiers Research Foundation.

- “Roster of the 47th P. V. Inf.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 26 October 1930.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- “The History of the Forty-Seventh Regt. P. V.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Lehigh Register, 20 July 1870.

- “W. A. Sponsler In Prison: The President of the Defunct Perry County Bank Jailed for Contempt.” Altoona, Pennsylvania: Altoona Tribune, 19 February 1896.

- “Up In Perry” (notice of Ephraim Clouser’s arrest and sanity hearing). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Harrisburg Telegraph, 22 September 1892.

You must be logged in to post a comment.