This home at the corner of Main and Carlisle Streets in Landisburg, Perry County, Pennsylvania was used as a stop on the Underground Railroad by men, women and children who were fleeing from slavery in America’s Deep South (photo circa 1900, public domain).

James Thomas Williamson was a tanning industry worker in Landisburg, Perry County, Pennsylvania during the outbreak of the American Civil War. His friends and family knew him as “Tom” or “J. T.”

Sadly, much more is known about his death than about his life.

Formative Years

Born in Perry County, Pennsylvania in 1826, James Thomas Williamson may have been the son or husband of a woman named Catharine McClure, according to several historical documents that have been verified to have been associated with him.

By the dawn of the American Civil War, he was a thirty-five-year-old resident of Landisburg, Perry County who was employed as a leather craftsman in Perry County’s prosperous tanning industry.

American Civil War

One of the things that is known for certain about James T. Williamson is that he enlisted for military service during the early months of the American Civil War. Following his enrollment in Bloomfield, Perry County, Pennsylvania on 20 August 1861, he officially mustered in for duty at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County as a corporal with Company D of the newly-formed 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry on 31 August.

Following a brief training period in light infantry tactics, Private J. T. Williamson and his company were sent by train with the 47th Pennsylvania to Washington, D.C. where they were stationed at “Camp Kalorama” on the Kalorama Heights near Georgetown, about two miles from the White House, beginning 20 September. Two days later, C Company Musician Henry D. Wharton penned these words to the Sunbury American newspaper in Northumberland County:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a setting [sic, set] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposefully erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men that, on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so adapt [sic, wrapped] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on discovering they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.

Col. Good, who has command of our regiment, is an excellent man and a splendid soldier. He is a man of very few words, and is continually attending to his duties and the wants of the Regiment.

…. Our Regiment will now be put to hard work; such as drilling and the usual business of camp life, and the boys expect and hope for an occasional ‘pop’ at the enemy.

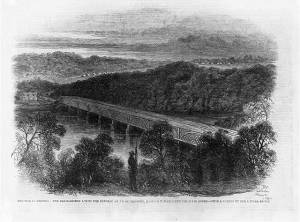

Chain Bridge across the Potomac above Georgetown looking toward Virginia, 1861 (The Illustrated London News, public domain).

Acclimated somewhat to their new life, the soldiers of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry subsequently became part of the Army of the United States when they were officially mustered into federal service on 24 September. Three days later, they were assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General Isaac Ingalls Stevens, which also included the 33rd, 49th and 79th New York regiments. By that afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were on the move again.

Ordered onward by Brigadier-General Silas Casey, the Mississippi rifle-armed 47th Pennsylvania infantrymen marched behind their Regimental Band until reaching Camp Lyon, Maryland on the Potomac River’s eastern shore. At 5 p.m., they joined the 46th Pennsylvania in moving double-quick (one hundred and sixty five steps per minute using thirty-three-inch steps) across the “Chain Bridge” marked on federal maps, and continued on for roughly another mile before being ordered to make camp.

The next morning, they broke camp and moved again. Marching toward Falls Church, Virginia, they arrived at Camp Advance around dusk. There, about two miles from the bridge they had crossed a day earlier, they re-pitched their tents in a deep ravine near a new federal fort under construction (Fort Ethan Allen). They had completed a roughly eight-mile trek, were situated close to the headquarters of Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith (also known as “Baldy”) and were now part of the massive U.S. Army of the Potomac (“Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Under Smith’s leadership, their regiment and brigade would help to defend the nation’s capital from the time of their arrival through late January when the men of the 47th Pennsylvania would be shipped south.

Once again, Company C Musician Henry Wharton recalled the regiment’s activities, noting, via his 29 September letter to the Sunbury American:

On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders.)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march the morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic, Lewinsville], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six tons of hay. A nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment….

The Big Chestnut Tree, Camp Griffin, Langley, Virginia, 1861 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Sometime during this phase of duty, as part of the 3rd Brigade, the 47th Pennsylvanians were moved to a site they initially christened “Camp Big Chestnut,” in reference to a large chestnut tree growing there. The site would eventually become known to them as “Camp Griffin,” and was located roughly ten miles from Washington, D.C.

On 11 October, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads. In a mid-October letter to his own family and friends, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin, the commanding officer of Company C, reported that Companies D, A, C, F, and I (the 47th Pennsylvania’s right wing) were ordered to picket duty after the regiment’s left-wing companies (B, E, G, H, and K) had been forced to return to camp by Confederate troops.

In his letter of 13 October, Musician Henry Wharton described the duties of the average 47th Pennsylvanian, as well as the regiment’s new home:

The location of our new camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic, chestnut] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets. Last night, however, they (the Rebels) calculated wide of their mark; some of the New York 33d boys were out on picket; some fourteen or fifteen shots were exchanged, when our side succeeded in bringing to the dust, (or rather mud,) an officer and two privates of the enemy’s mounted pickets. The officer was shot by a Lieutenant in Company H [?], of the 33d.

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually, but the hardest was on picket from last Thursday morning ’till Saturday morning – all the time four miles from camp, and both of the nights the rain poured in torrents, so much so that their clothes were completely saturated with the rain. They stood it nobly – not one complaining; but from the size of their haversacks on their return, it is no wonder that they were satisfied and are so eager to go again tomorrow. I heard one of them say ‘there was such nice cabbage, sweet and Irish potatoes, turnips, &c., out where their duty called them, and then there was a likelihood of a Rebel sheep or young porker advancing over our lines and then he could take take them as ‘contraband’ and have them for his own use.’ When they were out they saw about a dozen of the Rebel cavalry and would have had a bout with them, had it not been for … unlucky circumstance – one of the men caught the hammer of his rifle in the strap of his knapsack and caused his gun to fire; the Rebels heard the report and scampered in quick time….

On Friday morning, 22 October 1861, the 47th engaged in a divisional review, described by historian Lewis Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review that was monitored by the regiment’s founder and commanding officer, Colonel Tilghman H. Good — a formal inspection that was followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

As a reward — and in preparation for bigger things to come, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan obtained new Springfield rifles for every member of the 47th Pennsylvania.

1862

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were transported to Florida aboard the steamship S.S. Oriental in January 1862 (public domain).

Ordered to move from their Virginia encampment back to Maryland, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862. Marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church, they were transported to Alexandria, where they boarded the steamship City of Richmond and sailed the Potomac River to the Washington Arsenal, where they disembarked and were re-equipped. Subsequently marched to the Soldiers’ Rest in Washington, D.C., they were fed and given the opportunity to relax there. The next afternoon, they were marched to the railroad station, where they hopped aboard a train from the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland.

Arriving around 10 p.m., they disembarked and were marched to a barracks at the United States Naval Academy, where they bedded down for the night. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January) loading their equipment and supplies onto the S.S. Oriental.

During the afternoon of 27 January, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers began boarding the Oriental, enlisted men first, and then, per the directive of Brigadier-General Brannan, they steamed away at 4 p.m. and headed for Florida, which, despite its secession from the United States remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of several key federal installations.

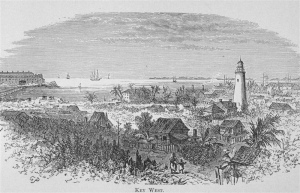

Lighthouse, Key West, Florida, early to mid-1800s (George M. Barbour, Florida for Tourists, Invalids, and Settlers,1881, public domain).

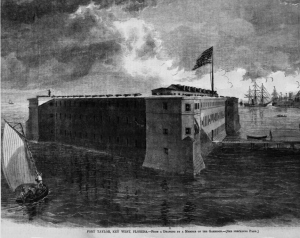

Arriving in Key West, Florida by early February 1862, the men of Company D and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers disembarked and were ordered to pitch their tents on the beach, where they rested and were subsequently directed to their respective quarters inside and outside of Fort Taylor. Assigned to garrison the fort, they drilled daily in infantry and artillery tactics, began strengthening the fortifications of this key federal installation and also began making infrastructure improvements to the city by felling trees and building new roads.

On 6 February 1862, Private J. T. Williamson put pen to paper to describe the regiment’s recent voyage. His account was subsequently published two weeks later in the 20 February edition of The Perry County Democrat:

For the Democrat

Army Correspondence.

Key West, Florida, Feb. 6th, 1862.

MR. J. A. MAGEE:Dear Sir — This day two weeks ago we pulled up stakes in Camp Griffin, Virginia, and started for the “Sunny South.” We left our Tents stand for the use of the 86th N. Y., who now occupy them and slung our Knapsack’s which we carried to the Vienna Railroad. We then got aboard the cars and went to Alexandria where we were then placed aboard a crazy steam Propeller which managed to carry us to Washington City. We landed at the Navy Yard and there exchanged our old arms for new improved Springfield Rifles. We remained in the city one night and next morning took the cars for Annapolis, where the Steam Ship Oriental was directed to report to receive us. We arrived at Annapolis in advance of the ship and were quartered in one of the buildings belonging to the Naval School, where, it is said, some of the most promising officers in the Pirate Navy were educated. The school was removed last Spring, I believe, to Fortress Monroe. — The buildings are numerous and the grounds splendidly laid out and includes about forty Acres; but everything now about the place indicated that the foul Fiend, Secession, has cast his blight upon it.

We remained in Annapolis from Friday until Tuesday morning at 9 o’clock, when we commenced embarking, (the Oriental having arrived in port the day after us.) The regiment was all aboard by four o’clock. She is a noble vessel. She was built last season and this was her second voyage. The Government has chartered her at one thousand dollars per day for six months as a Transport. By half-past four steam was up and the 47th bid farewell to Annapolis — many of us, perhaps, for ever. But a more joyous party never stepped aboard an Ocean Steamer. The Signal Gun was fired and our noble ship was ploughing through the briny waters of the Chesapeake. About seven o’clock on the first night we cast anchors, on account of the darkness, and in doing so, lost one of our anchors which caused us next day to stop at Fortress Monroe to procure another, which, by-the-dy, we failed to do, none being there not in use. Nothing of interest occurred in our passage down the Chesapeake to the fort, a distance of one hundred and four miles. We remained at anchor under the guns of the Fort one night. So much has been written about Fortress Monroe and the Rip-Raps, of late, that it would be a matter of supererogation in me to say anything about them, save that I do not want to be aboard the Fleet that attacks them. It strikes me it would be a very dangerous undertaking. Next morning, by daylight, we were rapidly steaming down the day. — About ten o’clock were opposite Cape Henry Light House, discharged our Pilot, “and went it alone,” the face of the Bay remained comparatively smooth until about four o’clock in the afternoon when the vessel began to pitch considerably more than was agreeable, but it was only a foretaste of what was to come. We were nearing Cape Hatteras, the Seven Heaven of Storms. The 47th will have cause long to remember the night we passed that Cape. Morning at length dawned to show us we were surrounded by a mad and surging ocean. We were crossing the Gulf stream with a heavy gale right ahead of us. Oh, how old Ocean pitched into us. I now can fully realize what a gale at sea means. During the entire day and night following the decks were washed by the waves breaking over the vessel. I got several most splendid duckings. During this day and night the regiment sickened with very few exceptions and such a scene as was enacted by the 47th I will not attempt to describe. It was both amusing and disgusting to those that were fortunate enough to be spared this cruel sickness.

Among the fortunate few that escaped was your humble servant, and hurrah for Perry county, the only officers aboard that escaped were Captains Woodruff and Kacy. Lieutenants Auchmuty and Stroop had a serious time of it for a day or two, but soon regained their usual health and are now looking better than ever. But I must hurry on. We went out some four hundred and fifty miles to sea in order to escape the Gulf stream; the water continued rough until we reached the Bahama Channel. We came in sight of the Bahama Islands on Sunday morning, about 9 o’clock. On that day we passed what mariners call the Hole in the Wall, a ledge of rocks extending out into the sea from Bbacca [sic] Island, through which the waters have worked an apparently round hole. — The Ocean here became perfectly calm, scarcely a ripple to be seen. In the mean time we had passed, in five days, from mid winter to mid summer. The weather here is delightful. On Sunday evening we came in sight of the Florida reefs and on Monday evening reached Key West, Florida — the most southern point of land in the United States. Not being able to enter the harbor at night, we lay on and off until morning, when we steamed into port and landed at the dock. In doing so we passed the Fort and it looks as though it might defy the navies of the world. We commenced disembarking soon after reaching the dock, our Company [Company D] among the first, and here the most beautiful scenery met my wondering eyes that I ever beheld. I cannot find language to express my admiration of the village of Key West. The Island is about seven miles long and two broad and is situated between the 24th and 25th degrees of north latitude. The village is on the extreme west end of it and contains about four thousand inhabitants, who appear to be courteous and polite in their manners and many of them intelligent, and what may be interesting to some of your readers, the judges in our Company say, the ladies are beautiful; but what pleases we [sic, me] most, or rather interests me most, is the beautiful gardens and plats [sic, plants] that surround each house in the village. Cocoa trees in any quantity in every direction, with clusters of fruit hanging to them; Almond trees, the Tree of Knowledge, upon which grows a fruit called the “Forbidden,” that partakes of both the nature of the Lemon and Orange, but much larger than either, said to be quite palatable. No wonder that a certain individual of distinction at an early day succeeded in fooling Mrs. Adam, if this be the same fruit he offered her. It is the most splendid looking fruit I ever saw. These, together with an hundred other varieties of trees, plants and shrubbery adorn every garden on the Island. If Eden were as beautiful as this village no doubt Adam felt the loss severely. We marched out of the village a short distance, stacked our arms, and commenced clearing off the ground to pitch our tents. The whole Island is covered clear up to the village with a growth of what we would call at home a thicket of underbrush. — There are fifty different kinds of bushes and plants, among those that grow so luxuriantly is the different varieties of the caxtus [sic, cactus], some of which reach a fabulous size. There is one standing close by me at least fifteen feet in height and the main stem near the roots would measure 9 inches in diameter. A soldier just told me it is called the Snake Caxtus [sic, Cactus] at home, on account of the numerous small stem that shoot strait up from the main stock [sic, stalk]. It will take us some time to clear off a spot large enough to encamp on, meantime we sleep in the open air and very pleasantly at that. Well, are we sons to stay here? My opinion is not. A large expedition is fitting out here. We are the advance. — Perhaps next letter from me may tell of scenes of blood. Twenty-seven mortar vessels are already following us from the North and no doubt many others are ordered. There was on board our own vessel 18 rifled cannon. Those on board the mortar vessels are said to be the largest ever cast. No doubt but a very extensive expedition is to be started from here to some important point on the coast of Florida. My letter has run to an unpardonable length and must close. The Company are all well with but two exceptions and they are not serious. Sergeants Cozier [sic, Kosier], Fertig, Topley, Corporal Reed, indeed all from Bloomfield, look and appear to enjoy themselves better than ever. Capt. Woodruff is the very picture of health and good humor and now, as the General said after an uninterrupted march of forty miles, it is about time to Halt.

Yours sincerely,

James T. Williamson.

Mr. J. A. Magee

P.S. My compliments and warmest thanks to Mrs. Magee for a splendid pair of socks I was so fortunate as to draw of her own knitting. The mail closes at 12 o’clock and it is now 11. All is hurry here as the Oriental will leave to-day. — When anything of importance occurs I will keep you posted. Remember us to all. Sun hot as ____ to-day.

J. T. W.

During the weekend of 14 February, the regiment introduced itself to area residents via a parade through the city’s streets. That Sunday, the 47th Pennsylvanians began mingling with locals at area church services.

Among the lighter moments, the regiment commemorated the birthday of President George Washington with a parade, a special ceremony involving the reading of Washington’s farewell address to the nation (first delivered in 1796), the firing of cannon at the fort, and a sack race and other games on 22 February. The festivities resumed two days later when the Regimental Band hosted an officers’ ball at which “all parties enjoyed themselves, for three o’clock of the morning sounded on their ears before any motion was made to move homewards,” according to Musician Henry Wharton. This was then followed by a concert by the regimental band on Wednesday evening, 26 February.

Next ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina, from early June through July, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers camped near Fort Walker before relocating roughly thirty-five miles away in the Beaufort District in the U.S. Army’s Department of the South.

Bay Street Looking West, Beaufort, South Carolina, circa 1862 (Sam A. Cooley, 10th Army Corps, photographer, public domain).

Frequently assigned to hazardous picket duty north of their main camp, they faced an increased risk of enemy sniper fire. Despite this danger, though, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan” for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing,” according to historian Samuel P. Bates.

Detachments from the regiment were also assigned to the Expedition to Fenwick Island (9 July) and the Demonstration against Pocotaligo (10 July).

But this phase of duty would be the last for Private J. T. Williamson, who was discharged on a surgeon’s certificate of disability from Beaufort, South Carolina on 5 August 1862. By that point in this phase of duty for the 47th Pennsylvania, multiple members of the regiment had been felled by one of several variants of intermittent fever, dysentery from the frequently unsanitary conditions and unsafe drinking water that the men were required to endure — or from the far more dangerous and often deadly typhoid fever.

Whatever had sickened Private Williamson had made him so frail that he was no longer able to perform even the most basic duties of a corporal — let alone endure any future marches or combat engagements under the hot southern sun. So, he was honorably discharged from the Union Army and sent home to Perry County, Pennsylvania by ship and train.

Just over three weeks later, he was gone.

Death and Interment

Corporal James T. Williamson’s military headstone, Landisburg Cemetery, Landisburg, Pennsylvania, 2002 (used with permission, courtesy of Judith Warner Bookwalter).

Described by a local news reporter as “sick and weary” when he reached Perry County, but also as a man who “still retained all that humor and kindliness of heart for which he was so well known,” James T. Williamson died while still in his mid-thirties on 29 August 1862. The complications from the disease he had contracted while in service to the nation with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had just simply been too much for his body to withstand.

According to The Perry County Democrat, he “reached home in time to die among his friends.”

Poor Tom! How often we have been regaled with his wit. After life’s fitful fever he sleeps well.

Following funeral services, J. T. Williamson was “buried with the honors of war by the citizens of Landisburg” at that community’s Landisburg Cemetery.

What Happened to James Williamson’s Family?

Researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story are still researching the lives of James Williamson’s family. Among the facts that have been uncovered so far are the confirmation that he was survived by a woman named “Catharine McClure,” who was identified on one federal government document (a U.S. Civil War Pension General Index Card) as his widow, but who was identified as his mother on another (the special 1890 federal census of Civil War soldiers, sailors and their dependents).

From those two documents it appears that this woman filed for, but may not have been not awarded, a U.S. Civil War Mother’s Pension (at least not initially). The date on which Catharine McClure filed that application, from Pennsylvania, was 24 November 1888.

It also appears, from the special veterans’ census, that Catharine McClure was a resident of Shippensburg in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania by the time that census was conducted in 1890.

Unfortunately, the trail goes cold from there.

Can You Help Solve This Mystery?

If you’re a descendant of James T. Williamson and can shed more light on his early years, please contact our researchers. He deserves to be remembered for more than just the circumstances of his death.

Sources:

- “Another Soldier Gone” (obituary of J. T. Williamson). New Bloomfield, Pennsylvania: The Democrat, 4 September 1862.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5;, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- “Florida’s Role in the Civil War,” in Florida Memory. Tallahassee, Florida: State Archives of Florida.

- Hain, Harry Harrison. History of Perry County, Pennsylvania. Including Descriptions of Indians and Pioneer Life from the Time of Earliest Settlement. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Hain-Moore Company, 1922.

- “McClure, Catherine, Mother of William, James T.” (mother of James T. Williamson), in U.S. Census (“Special Schedule. — Surviving Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, and Widows, etc.”: Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, 1890). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- “The History of the Forty-Seventh Regt. P. V.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Lehigh Register, 20 July 1870.

- Williamson, James T. “Army Correspondence: Key West, Florida, Feb. 6th, 1862” (letter sent by James T. Williamson to Mr. J. A. Magee). Bloomfield, Pennsylvania: The Perry County Democrat, 20 February 1862.

- Williamson, James T., in Civil War Muster Rolls (Company D, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Williamson, James T., in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 (Company D, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Williamson, James T. and McClure, Catharine, in U.S. Civil War Pension General Index Cards (widow’s application no.: 384479, filed from Pennsylvania, 24 November 1888). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.