Alternate Spellings of Surname: Piers, Pyers

A pre-teen when leaders from multiple southern states announced that they were intent on breaking up the United States, he was forced to grow up quickly when his father marched off to join the fight to preserve American’s Union. As his mother read his father’s letters to their family, he heard of regimental adventures in far off places, and was made increasingly aware of the very real hardships and heartaches that were being suffered by soldiers as they battled tropical diseases in the Deep South while also engaging in intense fighting with Confederate troops in often life-threatening, “minor” skirmishes and major combat situations.

His name was Samuel Hunter Pyers and, more than half a century after the American Civil War was over, he had his own tales of derring-do to tell his own children and those of his friends and neighbors.

He was, quite simply, an eyewitness to history.

Formative Years

A native of Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, Samuel Hunter Pyers was born on 13 March 1848, the son of Pennsylvania natives, William Pyers (1817-1864) and Matilda (Heddings) Pyers (1825-1908).

Court House, Sunbury, Pennsylvania, 1851 (James Fuller Queen, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

In 1860, he resided with his parents and younger brother, Franklin, in Sunbury, Northumberland County. His father supported the family through employment as a boatman.

At the age of twelve, Samuel watched his forty-one-year-old father, William Pyers, head off to war. They and other Sunbury residents were on pins and needles during that summer of 1861. The men of the local militia, also known as the “Sunbury Guards,” had just returned from their Three Months’ Service (from April to July) with Company F of the 11th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Company F held the distinction of being “early defenders” and were, in fact, the first unit to leave Northumberland County in response to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteer troops to protect the nation’s capital following the fall of Fort Sumter to Confederate forces.

Their feet had barely had the chance to make new impressions on Sunbury soil when many of these same men were informing their families that they were re-enrolling for three-year terms of military service and encouraging their neighbors and friends to join them in the fight with their new unit — the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Still calling themselves the Sunbury Guards, William Pyers and his fellow enlistees officially became part of Company C when they mustered in with the 47th Pennsylvania at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County from August through early September 1861. While there, they trained in light infantry tactics under the leadership of their company’s captain, John Peter Shindel Gobin, a Sunbury attorney who was respected within and beyond the borders of Northumberland County.

During the fall of 1861, Samuel’s father and the 47th Pennsylvania helped to defend the nation’s capital. By 1862, they were capturing Saint John’s Bluff (early October 1862). From 21-23 October, they were badly battered during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina.

Enrollment of Samuel H. Pyers for Civil War Service

Despite the all too frequent news of war casualties from Sunbury and its surrounding communities — and even efforts by his father to dissuade him from joining the fight, Samuel H. Pyers enrolled for military duty as soon as the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania deemed him old enough to serve. He enrolled at Sunbury on 23 November 1863, and mustered in as a musician with his father’s company (the Sunbury Guards/Company C) in the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, at Camp Curtin just four days later. At the age of fifteen, he was, in reality, still only a boy,

Military records describe him as being the same height as his father (5’8″ tall) with the same light hair, fair complexion and blue eyes.

Formerly a farmer by trade, he was now a “drum boy.” His new job required him to master a number of drum cadences that would be used to convey the directions of his company’s commanding officers to the company’s members. According to Civil War historian Michael Aubrecht:

Each drummer was required to play variations of the 26 rudiments. The rudiment that meant attack was a long roll. The rudiment for assembly was a series of flams while the rudiments for drummers call were a mixture of flams and rolls. The rudiment for simple cadence was open beating with a flam repeat. Additional requirements included the double stroke roll, paradiddles, flamadiddles, flam accents, flamacues, ruffs, single and double drags, ratamacues, and sextuplets….

Military drums were usually about 18” deep prior to the Civil War. Then they were shortened to 12”-14” deep and 16” in diameter in order to accommodate younger (and shorter) drummers. Ropes were joined all around the drum and were manually tightened to create tension that stiffened the drum head, making it playable. The drums were hung low from leather straps, necessitating the use of the traditional grip. Regulation drumsticks were usually made from rosewood and were 16”-17” in length. Ornamental paintings were very common for Civil War drums which often displayed pictures of Union eagles and Confederate shields.

…. The shells were usually made of ash, maple or similar pliable woods. Wooden hoops were used to reinforce the drum which was “tuned” by adjusting ropes that crisscrossed around the shell and provided tension on calfskin or sheepskin heads. The four strand snare was constructed from a bronze hoop-mounted strainer with a leather anchor.

His first duty station with Company C was at Fort Taylor in Key West, where the 47th Pennsylvania was stationed as part of the 10th Corps, U.S. Army’s Department of the South.

1864

Natchitoches, Louisiana (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 7 May 1864, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

On 25 February 1864, Samuel and William Pyers and their fellow members of the 47th set off for a phase of service in which the regiment would make history as the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign mounted by Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks from 10 March to 22 May.

“The Red River expedition started and on this we went under General Banks, and marched all the way up to Shreveport and climaxed our long tramp with a battle,” recalled Pyers in 1928 as he recounted his regiment’s Civil War experiences for the Lebanon Daily News.

Steaming aboard the Charles Thomas for New Orleans, the men arrived at Algiers, Louisiana on 28 February and were sent on by train to Brashear City. Following another steamer ride — this time to Franklin via the Bayou Teche — the 47th joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps.

From 14-26 March, the 47th battled difficult terrain and elements as it headed for the top of the L in the L-shaped state. Complicating things further, there were stretches during the campaign — sometimes five and six days long, said Pyers — that the soldiers of the 47th Pennsylvania went hungry.

On 8 April 1864, Second Lieutenant Alfred Swoyer and fifty-nine others were cut down during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (also known as the Battle of Mansfield). At that time, the village of Mansfield, Louisiana was strategically important to the Confederate States of America because it served as a vital communications hub for the Confederate Army.

After trekking roughly one hundred and fifty miles up the Red River, Banks’ Union forces were halted in their advance on Shreveport by Major-General Richard Taylor, and his Confederate troops. Both sides sparred with each other on and off all morning; that afternoon, Taylor ordered his troops to attack both flanks of the Union Army. The fighting raged until nightfall—after Banks ordered a third division into the fray.

The next day, the regiment’s sixty-eight-year-old standard bearer and fellow member of Company C, Color Sergeant Benjamin Walls, was wounded during more fierce fighting. “After the fight at Shreveport we dropped back to Pleasant Hill, Louisiana. But the name of the hill isn’t so fitting for here we had a rough and tumble fight and then went on a march that seemed to take up all over the south, so long did we tramp,” said Pyers.

Among the many members of the 47th wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill on 9 April 1864 were the regiment’s second in command, Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, and Samuel’s own father, Sergeant William Pyers, who was hit by enemy fire as he saved the flag when standard bearer Benjamin Walls fell in battle. Samuel’s father survived and continued to fight with the 47th.

Christened as “Bailey’s Dam” in reference to the Union officer who designed its construction, Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 was designed to facilitate Union gunboat travel (public domain).

“From the Hill we came back to Missouri Plain, there we fought a battle. From this place we crossed Cain [sic] River on a pontoon bridge and went to Alexandria, Louisiana.” That crossing occurred on 23 April via Monett’s Ferry, and the combat engagement came to be known as the Battle of Cane River.

“At this place we had to stop fighting and build dams. Huge dams to get the gun boats down the Mississippi River. It was a case of the army digging out the navy,” said Pyers of the Red River construction which lasted from 30 April through 10 May.

In a letter penned from Morganza, Louisiana on 29 May, fellow C Company Field Musician Henry Wharton described their mission and the weeks that followed:

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gunboats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people, will eat) so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the ironclads down the river. After a great deal labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’ The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order the day before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits [sic] on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gunboat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

On Sunday, May 15, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad wherewith the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. – We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed in line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired and we advanced ‘till dark, when the forces halted for the night, with orders to rest on their arms. – ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee.

Having entered Avoyelles Parish, they “rested on their arms” for the night, half-dozing without pitching their tents, but with their rifles right beside them. They were now positioned just outside of Marksville, Louisiana on the eve of the 16 May 1864 Battle of Mansura, which unfolded as follows, according to Wharton:

Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, the infantry advanced in line until they reached Mousoula [sic, Mansura], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain correctly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport [sic, Simmesport] on the Achafalaya [sic, Atchafalaya] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over. – The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of our army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.

After the surviving members of the 47th made their way through Simmesport and into the Atchafalaya Basin, they moved on to Morganza, where they made camp again. While there, the nine formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania in Beaufort, South Carolina (October-November 1862) and Natchitoches, Louisiana (5 April 1864) were officially mustered into the regiment between 20-24 June 1864.

The regiment then moved on once again, and arrived in New Orleans in late June.

As they did during their tour through the Carolinas and Florida, the men of the 47th had battled the elements and disease, as well as the Confederate Army, in order to continue to defend their nation.

Ironically, on the Fourth of July — “Independence Day” — the father and son duo learned from their superior officers that their independence from military life would not be happening anytime soon because the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had received new orders to return to the Eastern Theater of the war.

On 7 July 1864, Drummer Samuel Pyers and his father, Sergeant William Pyers were among the first members of his regiment to depart Bayou Country. Boarding the U.S. Steamer McClellan, they sailed out of the harbor at New Orleans with their fellow C Company soldiers, along with the members of Companies A, D, E, F, H, and I.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Following their arrival in Virginia, the members of those 47th Pennsylvania companies had a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln before joining up with the Union forces led by Major-General David Hunter and engaging in the Battle of Cool Spring in and around Snicker’s Gap, Virginia. According to C Company John Peter Shindel Gobin, an incident occurred on 12 July 1864, shortly they disembarked from their troop transport — one that “might have been exceedingly serious in the prosecution of the war” because it brought Lincoln “under the actual fire of the enemy in their attack upon Fort Stevens”:

We landed at the Navy Yard, were met by an officer with instructions to move out at once, leaving a detail to look after baggage and horses. Up the avenue and out Seventh St. we at once proceeded, and at intervals were met by handsomely uniformed officers, who urged us to hurry up double quick.

Officers and men moving along discussed the cause of all this, but with no intimation of trouble or information or instructions of what was needed until we heard the sound of artillery and later of musketry.

There appeared to be no unusual commotion in Washington – few people on the streets – nothing to indicate the presence of an enemy, until the sound of firing was heard. The day was very hot the column marched along until Fort Stevens was reached, when, to the great surprise of every one, it was evident that a fight was going on at the front. We halted, and then began the inquiry, ‘What’s up? Are those Johnnies? Where’s Grant?’

While waiting for new orders at Fort Stevens, members of the 47th struck up a conversation with an officer from another Union regiment and were told, “’Old Abe’s in the Fort.’”

This was so startling, as it was repeated from file to file, that everybody made a rush to get near enough to see him. There was no mistaking him. His tall figure and high hat made him prominent, and I think every man of the regiment had a look at him.

Our Corps badge resembled that of the 5th Corps, and to many inquiries, ‘Do you belong to the 5th Corps?’ the answer was, ‘No, to the 19th.’ Considerable curiosity was evinced to know where the 19th Corps was from, and great surprise was expressed as to how we had gotten there from New Orleans, as it was stated, just in time.

In the meantime, numerous officers had been circulating around, various orders had been received, but nobody seemed to know what to do with us, and the regiment stood awaiting definite instructions.

At last it came, to move out to the left and deploy, move forward and connect with Bidwell’s Brigade. As we came into line and moved out, a young staff officer rode down the line, shouting, ‘You are going into action under the eye of the President! He wants to see how you can fight.’ The answer was a shout and a rush. We met with but little opposition. A sparse picket line of dismounted cavalry got out of the way readily, other regiments came in on our left. We did not meet Bidwell’s Brigade, but passed over their battle ground, until, after nightfall, we passed over some of the ground they had fought over, and recognized the red cross of the 1st Division, 6th Corps, as being the fighters. They had evidently been on the extreme left of the line in action. We bivouacked that night near the remains of a burnt house which was said to be Montgomery Blair’s.

The fighting was virtually over before we arrived, but the camp was full of stories during the night as to what had occurred at Fort Stevens while the President was there. Evidently that fort was within the range of the artillery and the skirmishers of the Rebel Army, and it was rumored that General H. G. Wright had positively ordered the President to get out of the range of danger after an officer had been shot by his side.

Mr. Chittenden, Register of the Treasury, in his account of it says that when he reached the Fort, he found the President, Secretary Stanton and other civilians. A young colonel of the artillery, who appeared to be the officer of the day, was in great distress because the President would expose himself and paid little attention to his warnings. He was satisfied the Confederates had recognized him, for they were firing at him very hotly, and a soldier near him had just fallen with a broken thigh. He asked my advice, says Chittenden, for he said the President was in great danger. After some consultation the young officer walked to where the President was looking over the edge of the parapet and said, ‘Mr. President, you are standing within range of 500 Rebel rifles. Please come down to a safer place. If you do not it will be my duty to call a file of men and make you.’

‘And you would do quite right, my boy,’ said the President, coming down at once, ‘you are in command of this fort. I should be the last man to set an example of disobedience.’ He was shown to a place where the view was less extended, but where there was almost no exposure. As Mr. Chittenden was present and speaks from personal knowledge, I assume this to be a correct statement.

On 24 July, Captain Gobin was promoted to the regimental rank of major and was reassigned to the regiment’s central command staff.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Attached to the Middle Military Division, U.S. Army of the Shenandoah from August through November of 1864, it was at this time and place, under the leadership of legendary Union Major-General Philip H. Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, that the members of the 47th Pennsylvania would engage in their greatest moments of valor.

Of the experience, Samuel Pyers would later say it was “our hardest engagement.”

Records of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers confirm that the regiment was assigned to defensive duties in and around Halltown in early August 1864, and engaged in a series of back-and-forth movements between Halltown, Berryville, Middletown, Charlestown, and Winchester, Virginia as part of a “mimic war” being waged by Sheridan’s Union forces with those commanded by Confederate Lieutenant-General Jubal Early.

On 1 September 1864, First Lieutenant Daniel Oyster was promoted to the rank of captain of Company C. William Hendricks was promoted from second to first lieutenant, Sergeant Christian S. Beard was promoted to second lieutenant, Sergeant William Fry was promoted to the rank of first sergeant, and Private John Bartlow was promoted to the rank of sergeant. Private Timothy M. Snyder was also promoted to the rank of corporal that same day.

From 3-4 September, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers fought in the Battle of Berryville and engaged in related post-battle skirmishes with the enemy over subsequent days. On one of those days (5 September 1864), Captain Oyster was wounded at Berryville, Virginia.

Two weeks later, on 18 September, Color-Bearer Benjamin Walls, the oldest member of the entire regiment, was mustered out upon expiration of his three-year term of service — despite his request that he continued to be allowed to continue his service to the nation. Privates D. W. and Isaac Kemble, David S. Beidler, R. W. Druckemiller, Charles Harp, John H. Heim, former POW Conrad Holman, George Miller, William Pfeil, William Plant, and Alex Ruffaner also mustered out the same day upon expiration of their respective service terms.

Battle of Opequan

Inflicting heavy casualties during the Battle of Opequan (also known as “Third Winchester”) on 19 September 1864, Sheridan’s gallant blue jackets forced a stunning retreat of Jubal Early’s grays — first to Fisher’s Hill (21-22 September) and then, following a successful early morning flanking attack, to Waynesboro. These impressive Union victories helped Abraham Lincoln secure his second term as President. Recalling the battle years later, Sheridan noted:

My army moved at 3 o’clock that morning. The plan was for Torbert to advance with Merritt’s division of cavalry from Summit Point, carry the crossings of the Opequon at Stevens’s and Lock’s fords, and form a junction near Stephenson’s depot, with Averell, who was to move south from Darksville by the Valley pike. Meanwhile, Wilson was to strike up the Berryville pike, carry the Berryville crossing of the Opequon, charge through the gorge or cañon on the road west of the stream, and occupy the open ground at the head of this defile. Wilson’s attack was to be supported by the Sixth and Nineteenth corps, which were ordered to the Berryville crossing, and as the cavalry gained the open ground beyond the open gorge, the two infantry corps, under command of General Wright, were expected to press on after and occupy Wilson’s ground, who was then to shift to the south bank of Abraham’s creek and cover my left; Crook’s two divisions, having to march from Summit Point, were to follow the Sixth and Nineteenth corps to the Opequon, and should they arrive before the action began, they were to be held in reserve till the proper moment came, and then, as a turning-column, be thrown over toward the Valley pike, south of Winchester.”

By dawn on 19 September, the brigade from Wilson’s division, headed by McIntosh, succeeded in compelling Confederate pickets to flee their Berryville positions with “Wilson following rapidly through the gorge with the rest of the division, debouched from its western extremity with such suddenness as to capture a small earthwork in front of General Ramseur’s main line.” Although “the Confederate infantry, on recovering from its astonishment, tried hard to dislodge them,” they were unable to do so, according to Sheridan. Wilson’s Union troops were then reinforced by the U.S. 6th Army.

I followed Wilson to select the ground on which to form the infantry. The Sixth Corps began to arrive about 8 o’clock, and taking up the line Wilson had been holding, just beyond the head of the narrow ravine, the cavalry was transferred to the south side of Abraham’s Creek.

The Confederate line lay along some elevated ground about two miles east of Winchester, and extended from Abraham’s Creek north across the Berryville pike, the left being hidden in the heavy timber on Red Bud Run. Between this line and mine, especially on my right, clumps of woods and patches of underbrush occurred here and there, but the undulating ground consisted mainly of open fields, many of which were covered with standing corn that had already ripened.

“The 6th Corps formed across the Berryville Road” while the “19th Corps prolonged the line to the Red Bud on the right with the troops of the Second Division.” According to Irwin, the:

First Division’s First and Second Brigades, under Beal and McMillan, formed in the rear of the Second Division and on the right flank. Beal’s First Brigade was on the right of the division’s position, and McMillan’s Second Brigade deployed on the left and rear of Beal; in order of the 47th Pennsylvania, 8th Vermont, 160th New York, and 12th Connecticut, with five companies of the 47th Pennsylvania deployed to cover the whole right flank of his brigade and to move forward with it by the flank left in front. By this time, the Army of West Virginia had crossed the ford and was massed on the left of the west bank.

While the ground in front of the 6th Corps was for the most part open, the 19th Corps found itself in a dense wood, restricting its vision of both the enemy and its own forces.

“Much time was lost in getting all of the Sixth and Nineteenth corps through the narrow defile,” Sheridan observed, adding that, because Grover’s division was “greatly delayed there by a train of ammunition wagons … it was not until late in the forenoon that the troops intended for the attack could be got into line ready to advance.” As a result:

General Early was not slow to avail himself of the advantages thus offered him, and my chances of striking him in detail were growing less every moment, for Gordon and Rodes were hurrying their divisions from Stephenson’s depot across-country on a line that would place Gordon in the woods south of Red Bud Run, and bring Rodes into the interval between Gordon and Ramseur.

When the two corps had all got through the cañon they were formed with Getty’s division of the Sixth to the left of the Berryville pike, Rickett’s division to the right of the pike, and Russell’s division in reserve in rear of the other two. Grover’s division of the Nineteenth Corps came next on the right of Rickett’s, with Dwight to its rear in reserve, while Crook was to begin massing near the Opequon crossing about the time Wright and Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers] were ready to attack.

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union Army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces, Battle of Opequan, 19 September 1864 (Kurz & Allison, circa 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

More than a quarter of a century after the clash, Irwin conjured the spirit of the battle’s beginning:

About a quarter before twelve o’clock, at the sound of Sheridan’s bugle, repeated from corps, division, and brigade headquarters, the whole line moved forward with great spirit, and instantly became engaged. Wilson pushed back Lomax, Wright drove in Ramseur, while Emory, advancing his infantry [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers] rapidly through the wood, where he was unable to use his artillery, attacked Gordon with great vigor. Birge, charging with bayonets fixed, fell upon the brigade of Evans, forming the extreme left of Gordon, and without a halt drove it in confusion through the wood and across the open ground beyond to the support of Braxton’s artillery, posted by Gordon to secure his flank on the Red Bud road. In this brilliant charge, led by Birge in person, his lines naturally became disordered….

Sharpe, advancing simultaneously on Birge’s left, tried in vain to keep the alignment with Ricketts and with Birge…. At first the order of battle formed a right angle with the road, but the bend once reached, in the effort to keep closed upon it, at every step Ricketts was taking ground more and more to the left, while the point of direction for Birge, and equally for Sharpe, was the enemy in their front, standing almost in the exact prolongation of the defile, from which line, still plainly marked by Ash Hollow, the road … was steadily diverging.

As the battle continued to unfold, the disorganization affected the lines on both sides of the conflict. According to Irwin:

The 19th Corps Second Division was initially successful, but in its charge became disorganized; and the troops on the left in following the less obstructed area of the road which veared [sic] slightly left, soon opened up a gap on their right; while the remainder of the Union forces were moving straight ahead as they engaged the Confederates. This gap eventually reached 400 yards in width, an opportunity the Confederates soon exploited. Fortunately the Confederates were soon themselves disorganized by their advance, and encountering fresh Union troops on their right flank were halted. The Confederate attack on the right flank also achieved initial success, until halted by Beal’s first brigade.

McMillan had been ordered to move forward at the same time as Beal, and to form on his left. The five companies of the 47th Pennsylvania that had been detached to form a skirmish line on the Red Bud Run to cover McMillan’s right flank, had some how [sic] lost their way on the broken ground among the thickets, and, not finding them in place, McMillan had been obliged to send the remaining companies of the same regiment to do the same duty, and brought the rest of the brigade to the front to restore the line. The line then charged and drove the Confederates back beyond the positions where their attack had started. The initial engagement had lasted barely an hour, and by 1 PM was over. The right flank of the 19th Corps was held by the 47th Pennsylvania and 30th Massachusetts.

According to Sheridan:

Just before noon the line of Getty, Ricketts, and Grover moved forward, and as we advanced, the Confederates, covered by some heavy woods on their right, slight underbrush and corn-fields along their centre [sic], and a large body of timber on their left along the Red Bud, opened fire from their whole front. We gained considerable ground at first, especially on our left but the desperate resistance which the right met with demonstrated that the time we had unavoidably lost in the morning had been of incalculable value to Early, for it was evident that he had been enabled already to so far concentrate his troops as to have the different divisions of his army in a connected line of battle in good shape to resist.

Getty and Ricketts made some progress toward Winchester in connection with Wilson’s cavalry…. Grover in a few minutes broke up Evans’s brigade of Gordon’s division, but his pursuit of Evans destroyed the continuity of my general line, and increased an interval that had already been made by the deflection of Ricketts to the left, in obedience to instructions that had been given him to guide his division on the Berryville pike. As the line pressed forward, Ricketts observed this widening interval and endeavored to fill it with the small brigade of Colonel Keifer, but at this juncture both Gordon and Rodes struck the weak spot where the right of the Sixth Corps and the left of the Nineteenth should have been in conjunction, and succeeded in checking my advance by driving back a part of Ricketts’s division, and the most of Grover’s. As these troops were retiring I ordered Russell’s reserve division to be put into action, and just as the flank of the enemy’s troops in pursuit of Grover was presented, Upton’s brigade, led in person by both Russell and Upton, struck it in a charge so vigorous as to drive the Confederates back … to their original ground.

The success of Russell enabled me to re-establish the right of my line some little distance in advance of the position from which it started in the early morning, and behind Russell’s division (now commanded by Upton) the broken regiments of Ricketts’s division were rallied. Dwight’s division was then brought up on the right, and Grover’s men formed behind it….

No news of Torbert’s progress came … so … I directed Crook to take post on the right of the Nineteenth Corps and, when the action was renewed, to push his command forward as a turning-column in conjunction with Emory. After some delay … Crook got his men up, and posting Colonel Thoburn’s division on the prolongation of the Nineteenth Corps, he formed Colonel Duval’s division to the right of Thoburn. Here I joined Crook, informing him that … Torbert was driving the enemy in confusion along the Martinsburg pike toward Winchester; at the same time I directed him to attack the moment all of Duval’s men were in line. Wright was introduced to advance in concert with Crook, by swinging Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania and his other 19th Corps’ troops] and the right of the Sixth Corps to the left together in a half-wheel. Then leaving Crook, I rode along the Sixth and Nineteenth corps, the open ground over which they were passing affording a rare opportunity to witness the precision with which the attack was taken up from right to left. Crook’s success began the moment he started to turn the enemy’s left…

Both Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] and Wright took up the fight as ordered…. [A]s I reached the Nineteenth Corps the enemy was contesting the ground in its front with great obstinacy; but Emory’s dogged persistence was at length rewarded with success, just as Crook’s command emerged from the morass of the Red Bud Run, and swept around Gordon, toward the right of Breckenridge….”

As “Early tried hard to stem the tide” of the multi-pronged Union assault, “Torbert’s cavalry began passing around his left flank, and as Crook, Emory, and Wright attacked in front, panic took possession of the enemy, his troops, now fugitives and stragglers, seeking escape into and through Winchester,” according to Sheridan.

When this second break occurred, the Sixth and Nineteenth corps were moved over toward the Millwood pike to help Wilson on the left, but the day was so far spent that they could render him no assistance.” The battle winding down, Sheridan headed for Winchester to begin writing his report to Grant.

According to Irwin, although the heat of battle had cooled by 1 p.m., troop movements had continued on both sides throughout the afternoon until “Crook, with a sudden … effective half-wheel to the left, fell vigorously upon Gordon, and Torbert coming on with great impetuosity … the weight was heavier than the attenuated lines of Breckinridge and Gordon Could bear.” As a result, “Early saw his whole left wing give back in disorder, and as Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] and Wright pressed hard, Rodes and Ramseur gave way, and the battle was over.”

Early vainly endeavored to reconstruct his shattered lines [near Winchester]. About five o’clock Torbert and Crook, fairly at right angles to the first line of battle, covered Winchester on the north from the rocky ledges that lie to the eastward of the town…. Thence Wright extended the line at right angles with Crook and parallel with the valley road, while Sheridan drew out Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] … and sent him to extend Wright’s line to the south….

Sheridan, mindful that his men had been on their feet since two o’clock in the morning … made no attempt to send his infantry after the flying enemy….

Sheridan … openly rejoiced, and catching the enthusiasm of their leader, his men went wild with excitement when, accompanied by his corps commanders, Wright and Emory and Crook, Sheridan rode down the front of his lines. Then went up a mighty cheer that gave new life to the wounded and consoled the last moments of the dying….

Summing up the battle for Lincoln and Grant, Sheridan reported:

My losses in the Battle of Opequon were heavy, amounting to about 4,500 killed, wounded and missing. Among the killed was General Russell, commanding a division, and the wounded included Generals Upton, McIntosh and Chapman, and Colonels Duval and Sharpe. The Confederate loss in killed, wounded, and prisoners equaled about mine. General Rodes being of the killed, while Generals Fitzhugh Lee and York were severely wounded.

We captured five pieces of artillery and nine battle flags. The restoration of the lower valley – from the Potomac to Strasburg – to the control of the Union forces caused great rejoicing in the North, and relieved the Administration from further solicitude for the safety of the Maryland and Pennsylvania borders. The President’s appreciation of the victory was expressed in a despatch [sic] so like Mr. Lincoln I give a fac-simile [sic] of it to the reader. This he supplemented by promoting me to the grade of brigadier-general in the regular army, and assigning me to the permanent command of the Middle Military Department, and following that came warm congratulations from Mr. Stanton and from Generals Grant, Sherman and Meade.

“The losses of the Army of the Shenandoah, according to the revised statements compiled in the War Department, were 5018, including 697 killed, 3983 wounded, 338 missing,” per revised estimates by Irwin. “Of the three infantry corps, the 19th, though in numbers smaller than the 6th, suffered the heaviest loss, the aggregate being 2074 [314 killed, 1554 wounded, 206 missing]. Conversely, Early “lost nearly 4000 in all, including about 200 prisoners; or as other sources reported, anywhere from 5500 to 6850 killed, wounded, and missing or captured.”

Despite the significant number of killed, wounded and missing on both sides of the conflict, casualties within the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were surprisingly low. Among the wounded were C Company Corporal Timothy Matthias Snyder, who was wounded slightly in the knee, and Privates William Adams (E Company), Charles Pfeiffer (B Company), who lost the forefinger of his right hand, J. D. Raubenold (B Company), and Edward Smith (E Company).

Miraculously, the father and son duo of Sergeant William Pyers and his drummer boy-son, Samuel, had made it through without a scratch.

On 23-24 September, Colonel Tilghman H. Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander mustered out of the 47th, their contributions to a grateful nation more than met.

Heartache at Cedar Creek

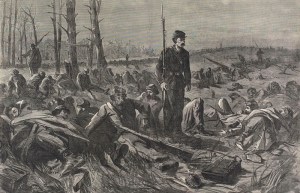

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, “Surprise at Cedar Creek,” captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle-pit positions, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

On 19 October, Early’s Confederate forces briefly stunned the Union Army, launching a surprise attack at Cedar Creek, but Sheridan was able to rally his troops during what is known today as the Battle of Cedar Creek. Intense fighting raged for hours and ranged over a broad swath of Virginia farmland. Weakened by hunger wrought by the Union’s earlier destruction of crops, Early’s army gradually peeled off, one by one, to forage for food while Sheridan’s forces fought on, and won the day.

A tide-turning day for the Union, it was an extremely costly engagement for Pennsylvania’s native sons. The 47th experienced a total of one hundred and seventy-six casualties during the Cedar Creek encounter alone, including: Captain Edward Minnich (killed at Cedar Creek 19 October), Captain John Goebel and Corporal Thomas Miller (both mortally wounded at Cedar Creek 19 October), and Sunbury Guards’ Privates James Brown (a carpenter), Jasper B. Gardner (a railroad conductor) and George W. Keiser (an eighteen-year-old farmer)—all killed in action on 19 October.

Worst of all for the young drummer, his father, Sergeant William Pyers, the very same courageous soldier who was wounded while protecting the colors at Pleasant Hill, also departed from the field of battle forever that terribly successful day at Cedar Creek.

“He was mowed down during the fight and buried on the battle ground.”

The reporter from the Lebanon Daily News who captured Pyers’ memories in 1928 noted that Samuel was still too traumatized, sixty-four years later, to talk in depth about his father’s death. (The remains of Samuel’s father, Sergeant William Pyers, were later exhumed by the federal government, and reinterred at the Winchester National Cemetery in Winchester, Virginia.)

After Cedar Creek, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers mourned their dead and recuperated. Stationed at Camp Russell near Winchester from November through most of December, they were ordered to march again — five days before Christmas — for outpost duty at Camp Fairview in Charlestown, West Virginia.

1865

Soldiers from an unidentified Union Army regiment guard The Old Nashville, the engine which powered the funeral train of President Lincoln (April 1865, public domain).

Assigned first to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah in February, the men of the 47th were ordered back to Washington, D.C. 19 April to defend the nation’s capital again — this time following President Lincoln’s assassination. “While we were still in Washington, President Lincoln was killed. I am proud to say that I was a guard at the funeral from Washington to the Relay House.”

Letters sent to family and friends back home from several other members of the 47th document that at least part of the regiment was also assigned to guard duty at the prison where the key Lincoln assassination conspirators were being held during the early days of their confinement and trial, which began on 9 May 1865. During this phase of duty, the regiment was headquartered at Camp Brightwood in the Brightwood section of Washington, D.C.

While serving in Dwight’s Division, 2nd Brigade, U.S. Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, Samuel H. Pyers and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers also participated in the Union’s Grand Review. on 23 May.

Unidentified regiment passes presidential reviewing stand, Grand Review of the Armies, 23 May 1865 (Matthew Brady, Library of Congress, public domain).

Reconstruction Duties

On their final swing through the South, the 47th served in Savannah, Georgia in early June as part of the 3rd Brigade, Dwight’s Division, U.S. Department of the South, and in Charleston and other parts of South Carolina beginning in June.

Garrisoning the city with the 47th Pennsylvania were the members of the 165th New York Volunteers, companies of the 3rd Rhode Island Artillery, and the 54th Massachusetts Volunteers. The first military unit assembled in the North comprised of Black soldiers, the trailblazing 54th was renowned for its gallantry and celebrated in the 1989 movie, Glory, starring Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman and Matthew Broderick.

Finally, on Christmas Day, 1865, at Charleston, South Carolina, the men of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers began to be honorably mustered out, a process which took more than a week.

On 2 January 1866, Samuel Pyers was finally discharged and sent home by steamship and train to Philadelphia, where, at Camp Cadwalader, he was paid for his service and given his honorable discharge papers.

Not Done

After briefly reconnecting with his family and friends back home in Northumberland County, Samuel Hunter Pyers chose to re-enlist in the military. In late 1866, he mustered in with Company I of the U.S. Army’s 30th Infantry. After initially being stationed in Omaha, Nebraska, Samuel Pyers and Company I were sent to Hot Springs, Utah to guard the Union Pacific Railway as it was being built. “Here we had a number of scrimmages with the Indians.”

He was then sent on to the Black Hills before eventually mustering out for good. “I was through the west fighting for three years and was finally discharged in 1869.”

Return to Civilian Life

Afterward, Samuel Pyers finally returned home to Northumberland County for good and, sometime around 1875, married Elizabeth Hoover. The couple welcomed a daughter, Jennie Alberta Pyers (1876-1918), on 10 January 1876. In 1880, the family resided in Sunbury, but before half a decade could pass, Samuel’s wife preceded him in death.

On 20 September 1885, Samuel married native Pennsylvanian, Sarah Ann Halderman (1869-1943), in Bellefonte, Centre County. They welcomed their first child, Samuel’s namesake — Samuel H. Pyers, in September 1886, and their first daughter Mary M. Pyers, sometime around 1888. Church records indicate, sadly, that the younger Samuel H. Pyers died on 10 December 1889, and was interred in the lower section of the Sunbury Cemetery.

Following the births of their first two children were sons William (1890-1966), Leroy (1892-1918) and Chester Grant Pyers (1894-1957), and daughter Dorathea Elizabeth Pyers (1897-1974). (Leroy Pyers died at the U.S. Army camp at Newport News, Virginia after becoming ill while serving with Company H of the 48th Infantry. Dora married Camden, New Jersey native, Robert Russell Blair, and passed away in New Jersey. Chester Pyers died in Lebanon, Pennsylvania; his older brother William passed away in Maplewood, New Jersey.)

In 1897, Jennie, Alberta Pyers, Samuel’s daughter from his first marriage, wed William Nelson (1870-1938), a native of Sweden.

On 3 April 1898, Samuel and Sarah welcomed another son, John L. Pyers (1898-1916), but, tragedy struck again when Samuel’s brother, Frank C. Pyers, passed away in Sunbury on 26 April 1899 in Sunbury at the young age of forty-five years, eleven months and thirteen days.

As the new century progressed for Samuel and Sarah, now in Lebanon County, they welcomed their final son, Nelson. Born in 1901, he survived just one year, nine months and thirteen days, and was buried in Lebanon in March 1902, according to the burial records of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church.

Daughters Alice May (1904-1990), Helen Mildred (1909-1989) and Winifred Pauline (1912-1997) completed the family. (Alice May Pyers resided in Whittier, California after marrying and taking the surname Weide. She passed away in Los Angeles County, California. Winifred Pauline Pyers married Henry Frank Boyer, and passed away in Lebanon, Pennsylvania after a long, full life. A former employee of Sowers Printing in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, Helen Mildred Pyers never married, and passed away at the Charlton Methodist Hospital in Dallas, Texas.)

In 1910, Samuel and his family were once again living in Sunbury, Northumberland County, but by 1920, he and Sarah had returned to Lebanon County with daughters Alice, Helen and Winifred. They worshipped at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Lebanon.

Samuel Hunter Pyers (with drum) was photographed with his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers at their annual reunion in Allentown in 1923 (public domain).

In 1923, he attended the reunion of the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers in Allentown, and was photographed, holding his old drum, while standing in front of the city’s Odd Fellows Hall with a group of his former comrades.

Death and Interment

On 3 November 1931, Samuel Hunter Pyers died in Lebanon, Pennsylvania from uremic poisoning related to the failure of his heart and kidneys. Three days later, he was interred at the Mount Lebanon Cemetery in Lebanon.

He was survived by his wife, Sarah, who was residing at the Pyers’ Lebanon home with daughters, Helen and Winifred Pyers; daughters Mrs. Warren Dale and Mrs. George H. Schropp (Lebanon), and Mrs. Robert Blair (Maple Shade, New Jersey); and sons Chester Pyers (Jersey City, New Jersey) and William Pyers (Maplewood, New Jersey), as well as sixteen grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Newspapers of the period briefly reported his passing on 5 November:

Pyers – In Lebanon, on the 3rd inst., Samuel H. Pyers, aged 83 years, 5 months and 80 days. Funeral on Friday morning at 10 o’clock form the late residence at 416 South Lincoln Avenue. Services at the residence. Interment at Mt. Lebanon.

The next day, local newspapers then also described his funeral:

Military Burial Given Samuel Hunter Pyres: Services at Grave in Charge of Local Body of V. F. W.: Rev. Rodney Brace Officiated at the House and Brief Words at the Cemetery

A military burial was tendered Samuel Hunter Pyers of 416 Sounth Lincoln Avenue, deceased Civil War veteran this morning, in charge of the Fuhrman Post. Veterans of Foreign Wars.

Rev. Rodney Brace, rector of the St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, officiated at the services held at the residence and a brief service at the cemetery. Burial took place at the Mt. Lebanon cemetery. All arrangements were in charge of the Arnold Undertaking Establishment, 712 Chestnut street.

* To view more of the key U.S. Civil War Pension records related to William and Samuel Pyers and their family, visit our Pyers Family Collection.

Sources:

- Aubrecht, Michael. “A History of Civil War Drummer Boys (Part 1).” Fredericksburg, Virginia: Emerging Civil War, 27 July 2016.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Civil War Veterans’ Card File. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Death and Burial Records, in Records of Zion Lutheran Church, Sunbury, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania (Reel 233), and in Records of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, Lebanon, Lebanon County, in Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- Pennsylvania Veteran’s Burial Cards (Samuel H. Pyers). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Department of Military and Veterans Affairs.

- Roberts, John. “Civil War Drum Calls” (video performance of the various calls used by Union Army drummer boys to call troops into formation and direct their movements in combat and non-combat situations; based on instructions provided to drummers in “Infantry Tactics” by Brigadier-General Silas Casey of the U.S. Army). YouTube: 19 September 2018, retrieved online 28 April 2024.

- “S. H. Pyers Was Drummer Boy in Civil War.” Lebanon, Pennsylvania: Lebanon Daily News, 16 July 1928.

- “Samuel Pyers at the Funeral of Abe Lincoln (Samuel Pyers’ obituary).” Lebanon, Pennsylvania: Lebanon Semi-Weekly News, 5 November 1931.

- “Samuel Hunter Pyers and Military Burial Given Samuel Hunter Pyers: Services at Grave in Charge of Local Body of V. F. W.: Rev. Rodney Brace Officiated at the House and Brief Words at the Cemetery (death notice and funeral description).” Lebanon, Pennsylvania: Lebanon Daily News, 5-6 November 1931.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- U.S. Census (1860, 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930). Washington, D.C. and Pennsylvania: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Wharton, Henry D. Letters from the Sunbury Guards, 1861-1868. Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American.

You must be logged in to post a comment.