Alternate Spellings of Surname: Gray, Grey

Raised to become a farmer during his formative years in the great Keystone State of Pennsylvania, Joseph Berry Gray was also encouraged by his parents, church leaders and public school teachers to become a civic leader who would have the skills, desire and wisdom to make life better not just for himself, but for his fellow Americans.

He was also the last surviving veteran of the American Civil War living in the community of Newton Hamilton, Mifflin County, Pennsylvania at the time of his death in 1927.

Formative Years

Born in Lack Township, Juniata County, Pennsylvania on 14 July 1843, Joseph Berry Gray was a son of Beale Township, Juniata County native and first-generation American Joseph Gray (1808-1898), who was a farmer, and Mary Elizabeth (Harris) Gray (1813-1851), who was a native of the town of Concord in Franklin County, Pennsylvania.

* Note: Joseph Berry Gray’s paternal grandfather, James Gray (1763-1847), had settled in Pennsylvania after emigrating from Ireland during the late 1700s. He subsequently began to homestead and farm land that was located in what later became Juniata County, and also began to raise livestock there. Married to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania native Rebecca Shafer, they became the parents of seven children: Robert, James, Samuel, John, Joseph, Catharine, and Polly, who later married a member of the Berry family.

Educated in the common schools of Juniata County, Joseph B. Gray was raised in Lack Township with his older siblings, Martha Dillon Gray (1831-1901), who had been born in Beale Township on 19 December 1831 and would later wed John R. Arnold (1833-1904), circa 1856; James Harris Gray (1835-1915), who had been born on 22 January 1835 and would later serve as a private with Company H of the 126th Pennsylvania Volunteers during the American Civil War, before marrying Margaret McWilliams (1835-1907); William S. Gray (1837-1891), who had been born in Lack Township on 11 March 1837, would also later serve with Company H of the 126th Pennsylvania Volunteers and would later wed Mary Jane Gilbert (1846-1935); John S. Gray (1839-1921), who had been born in Lack Township on 9 January 1839 and would later wed Mary Elizabeth Cook (1852-1920), circa 1868; and Thomas Gray (1841-1870), who was born on 25 May 1841 and would also later serve with Company H of the 126th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

By 1846, Joseph B. Gray was no longer the baby of the family, thanks to the arrival of his younger brothers, Alexander Cooper Gray (1846-1917), who was born in Mifflin, Juniata County on 17 June 1846 and would later wed Sarah Pilgrim McCullough (1843-1911); and Robert S. Gray (1847-1864), who was born on 2 August 1847.

As he became old enough, Joseph B. Gray began helping his father and older siblings perform the labor-intensive work on the Grays’ busy family farm. By 1850, he and his older siblings, Martha, James, William, and Thomas were all enrolled in, and regularly attending, the common schools in their county.

Sadly, their often mundane routine was destabilized the following year when their mother died at the age of thirty-eight in Beale Township on 25 April 1851. Following funeral services, she was laid to rest at the Upper Tuscarora Presbyterian Cemetery in Warerloo, Juniata County.

Later that same year, their father remarried, taking as his second wife, Leah Barton (1827-1899), who was in her mid-twenties on their wedding day. Multiple children soon followed — each of whom was a half-sibling to Joseph Berry Gray: Samuel B. Gray (1852-1873), who was born in 1852 but survived only to his early twenties; Nancy Elizabeth Gray (1853-1938), who was born in Lack Township on 30 June 1853 and would later wed William Jacob Eberts (1849-1935); Harvey Baxter Gray (1854-1930), who was born on 19 September 1854 and would later wed Hannah Jane Varner (1857-1909); George Washington Gray (1856-1891), who was born in East Waterford, Juniata County on 6 February 1856) and would later wed Annie M. Conn; Calvin B. Gray (1857-1930), who was born on 23 November 1857 and who would later wed Mary E. Crouse (1864-1934) in 1887 and work for the Lewistown and Reedsville Trolley Company; Calvin’s twin sister, Mary Mason Gray (1857-1942), who was also born on 23 November 1857, but went on to marry David Shellenberger Varner (1854-1928); and David Gray (1859-1860), who was born on 16 November 1859.

By mid-July of 1860, Joseph B. Gray and his brother Thomas were still helping their father and stepmother with many of the chores on the Gray family’s farm in Peru Mills, Lack Township. Also residing at the family’s homestead that year were their younger siblings, Alexander and Robert, and their younger half-siblings: Samuel, Nancy, Harvey, George, Calvin, Mary, and David, who subsequently died at the age of ten months, just three months later, on 13 October 1860.

“The Union Is Dissolved” (announcement of South Carolina’s secession from the United States, broadside, Charleston Mercury, 20 December 1860, U.S. Library of Congress and National Museum of American History, public domain; click to enlarge).

As if that were not enough tragedy for one family or the community they called home, they and their fellow Pennsylvanians faced a future of terrible uncertainty as eleven of fifteen slaveholding states in America were threatening to rip the United States of America apart.

Sadly, their fears were made real as the first tear in their nation’s fabric was made on 20 December 1860, when South Carolina’s leaders announced their state’s secession from the Union.

American Civil War

During the first year of the American Civil War, Joseph B. Gray and his older brothers continued to help their father keep the family farm running, as yet another half-sibling was welcomed at their home. Rebecca Ellen Gray (1862-1928), who would later wed James A. Smith (1854-1940), was born on 25 April 1862.

But their family’s harmony would be disrupted during the summer that year, as three of Joseph B. Gray’s older siblings — James, Thomas and William — made the decision to enlist in the Union Army. Following their enrollment for military service, the trio mustered in at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County on 14 August 1862 as privates with Company H of the 126th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Given basic training in light infantry tactics, they were subsequently transported by rail, on 15 August, to Washington, D.C., where they then were ordered to cross the Potomac River and make camp at Fort Albany. Breaking camp a week later, they and their fellow 126th Pennsylvanians marched to Cloud’s Mills,Virginia and were attached to the brigade of Brigadier-General E. B. Tyler, who ordered that they be given two additional weeks of training. Stationed there until 12 September, they marched toward Meridian Hill. Ordered to march toward Antietam, Maryland on 14 September, they reached the Monocacy on 16 September. Encamped there until mid-afternoon the next day, they finally reached the battlefield at Antietam the next morning and were assigned to the reserve units of the U.S. Army of the Potomac that were led by Porter. As the fighting drew to a close, without their having seen action, they were ordered to make camp at Sharpsburg, Maryland. Stationed there until 30 October, they were then moved to Falmouth, Virginia, where they remained until 19 November. According to historian Samuel P. Bates:

At four o’clock on the morning of the eleventh of December, [the 126th Pennsylvania] moved from camp for its initial battle. For two days it was held in suspense, the music of bands and the heavy booming of Burnside’s cannon filling the air. On the 13th the brigade crossed the Rappahannock, on the upper bridge, and passing up through the town, was led at half-past three out on the Telegraph Road to a low meadow on the right, where it was exposed to a heavy fire of artillery, without shelter and without the ability to offer the least resistance…. After a little delay it was ordered to the left of the road, under cover of a hill. The road was swept by the enemy’s shells, and the bullets of his sharp-shooters….Three fruitless attempts had already been made to carry the frowning heights above and now Humphreys’ Division was ordered up for a final charge…. Forming his brigade in two lines, the One Hundred and Twenty-sixth on the right of the second line, with orders to the men not to fire, but rely solely upon the bayonet, Tyler sounded the charge. Forward went that devoted brigade, uttering heroic cheers, ascending the hill in well ordered lines, and on past the brick house on Marye’s Hill, over the prostrate lines of the last charging column, and up within a moment’s dash of the stone-wall where the enemy lay. But now that fatal wall was one sheet of flame, and to add to the horror of the situation, the troops in the rear opened, every flash in the twilight visible. Bewildered, and for a moment irresolute, the troops commenced firing. This was fatal. The momentum of the charge was lost, and staggering back to the cover of the house, and desending the declivity, re-formed at the foot of the hill. At the head of his men, heroically urging them on at the farthest point in the charge Colonel Elder fell, severely wounded. The loss in that brief charge was twenty-seven killed, fifty wounded, and three missing.

Afterward, Union Major-General Joseph Hooker was reported to have said, “No prettier sight was ever seen than the charge of that division.” But the Battle of Fredericksburg had proven to be a costly loss for the Union Army, as would their next engagement — the ill-fated “Mud March” led by Union Major-General Ambrose Burnside from 20-24 January 1863.

Three days later, on 27 January, Private James H. Gray was promoted to the rank of corporal. Encamped at Falmouth until 27 April, the 126th Pennsylvania Volunteers were assigned next to the Chancellorsville Campaign through 6 May.

Participants in the carnage of the Battle of Chancellorsville, which began on 1 May 1863, the Gray brothers were nearly reduced from a trio to a duo when Corporal James Harris Gray was declared as missing in action on 3 May 1863. Fortunately for the Gray family, he was later found and given treatment for a leg wound that he had sustained in combat. He and his brothers, Privates Thomas and William S. Gray, were then all mustered out with the other members of their company — just over two weeks later (on 20 May 1863), and were sent home to Pennsylvania.

Undeterred by the brush with death that his brothers had experienced, Joseph B. Gray was determined to do his part to preserve America’s Union, and began making plans to enter the fight as the war dragged on into another New Year.

1864

On 23 February 1864, Joseph Berry Gray enrolled for military service in Harrisburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. Promised one hundred and eighty dollars of bounty pay for enlisting in the Union Army (the equivalent of roughly two thousand and twenty-four U.S. dollars in 2025), he was then officially mustered in there that same day as a private with Company C of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, which was about to make history as the only regiment from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to serve in the Union’s 1864 Red River Campaign across Louisiana.

He did not actually participate in that campaign, however, according to the 47th Pennsylvania’s muster rolls, which documented that his first activity with the regiment occurred on 18 September 1864 — when he joined the regiment from a recruiting depot, while the 47th Pennsylvania was stationed at Berryville, Virginia. as part of the U.S. Army of Shenandoah under the command of legendary Union Major-General Philip H. Sheridan.

* Note: Tragically, after Joseph B. Gray had enrolled for military service in Harrisburg, his family went through further upheaval. On 17 March 1864, his younger brother, Robert S. Gray, died at the age of sixteen and was subsequently interred at the Upper Tuscarora Presbyterian Cemetery in Waterloo, Juniata County. Then, on 29 March 1864, his father’s second wife, Leah (Barton) Gray, gave birth to yet another child — Alice Christian Gray (1864-1906), who became Joseph B. Gray’s ninth half-sibling and his sixteenth sibling all told. (Born in Waterloo, Alice would later go on to wed James Barnhart Beckenbaugh.)

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

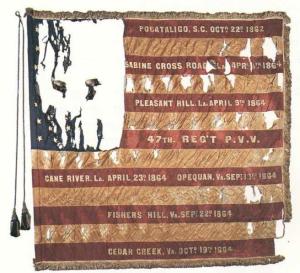

First State Color, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (presented to the regiment by Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin, 20 September 1861; retired 11 May 1865, public domain).

The day after Private Joseph B. Gray met up with his regiment, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry fought in the Battle of Opequan, helping to secure a Union Army victory on 19 September 1864 that significantly raised U.S. President Abraham Lincoln’s chance of reelection. Having just joined his regiment, Private Gray was not involved in that battle, however, according to his own post-war accounts of his war-time service. A brand new recruit, he had yet to receive his basic training in infantry tactics, and would have been deemed more of a hindrance than help to his fellow soldiers.

He was, however, deemed well enough trained to take part in the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah’s next tide-turning combat experience.

Battle of Cedar Creek

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, “Surprise at Cedar Creek,” captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle-pit positions, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

On 19 October 1864, the Confederate forces of Lieutenant-General Jubal Early briefly stunned the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah, launching a surprise attack at its Cedar Creek encampment, but that attack was ultimately blunted by Union Major-General Philip Sheridan, who mounted his horse, Rienzi, rode to the scene of the impending disaster and rallied his troops to an epic victory in what is known today as the Battle of Cedar Creek.

Intense fighting raged for hours and ranged over a broad swath of Virginia farmland. Weakened by hunger wrought by the Union’s earlier destruction of crops across the region, Early’s army gradually peeled off, one by one, to forage for food while Sheridan’s forces fought on. According to Union General Ulysses S. Grant:

On the 18th of October Early was ready to move, and during the night succeeded in getting his troops in the rear of our left flank, which fled precipitately and in great confusion down the valley, losing eighteen pieces of artillery and a thousand or more prisoners [during the Battle of Cedar Creek]. The right under General Getty maintained a firm and steady front, falling back to Middletown where it took a position and made a stand. The cavalry went to the rear, seized the roads leading to Winchester and held them for the use of our troops in falling back, General Wright having ordered a retreat back to that place.

Sheridan having left Washington on the 18th, reached Winchester that night. The following morning he started to join his command. He had scarcely got out of town, when he met his men returning, in panic from the front and also heard heavy firing to the south. He immediately ordered the cavalry at Winchester to be deployed across the valley to stop the stragglers. Leaving members of his staff to take care of Winchester and the public property there, he set out with a small escort directly for the scene of the battle. As he met the fugitives he ordered them to turn back, reminding them that they were going the wrong way. His presence soon restored confidence. Finding themselves worse frightened than hurt the men did halt and turn back. Many of those who had run ten miles got back in time to redeem their reputation as gallant soldiers before night.

Provided with inadequate intelligence by his staff by that fateful morning, Sheridan had begun his day at a leisurely pace, clearly unaware of the potential disaster in the making:

Toward 6 o’clock the morning of the 19th, the officer on picket duty at Winchester came to my room, I being yet in bed, and reported artillery firing from the direction of Cedar Creek. I asked him if the firing was continuous or only desultory, to which he replied that it was not a sustained fire, but rather irregular and fitful. I remarked: ‘It’s all right; Grover has gone out this morning to make a reconnaissance, and he is merely feeling the enemy.’ I tried to go to sleep again, but grew so restless that I could not, and soon got up and dressed myself. A little later the picket officer came back and reported that the firing, which could be distinctly heard from his line on the heights outside of Winchester, was still going on. I asked him if it sounded like a battle, and as he again said that it did not, I still inferred that the cannonading was caused by Grover’s division banging away at the enemy simply to find out what he was up to. However, I went down-stairs and requested that breakfast be hurried up, and at the same time ordered the horses to be saddled and in readiness, for I concluded to go to the front before any further examinations were made in regard to the defensive line.

We mounted our horses between half-past 8 and 9, and as we were proceeding up the street which leads directly through Winchester, from the Logan residence, where Edwards was quartered, to the Valley pike, I noticed that there were many women at the windows and doors of the houses, who kept shaking their skirts at us and who were otherwise markedly insolent in their demeanor, but supposing this conduct to be instigated by their well-known and perhaps natural prejudices, I ascribed to it no unusual significance. On reaching the edge of town I halted a moment, and there heard quite distinctly the sound of artillery firing in an unceasing roar. Concluding from this that a battle was in progress, I now felt confident that the women along the street had received intelligence from the battlefield by the ‘grape-vine telegraph,’ and were in raptures over some good news, while I as yet was utterly ignorant of the actual situation. Moving on, I put my head down toward the pommel of my saddle and listened intently, trying to locate and interpret the sound, continuing in this position till we had crossed Mill Creek, about half a mile from Winchester. The result of my efforts in the interval was the conviction that the travel of the sound was increasing too rapidly to be accounted for by my own rate of motion, and that therefore my army must be falling back.

At Mill Creek my escort fell in behind, and we were going ahead at a regular pace, when, just as we made the crest of the rise beyond the stream, there burst upon our view the appalling spectacle of a panic-stricken army – hundreds of slightly wounded men, throngs of others unhurt but utterly demoralized, and baggage-wagons by the score, all pressing to the rear in hopeless confusion, telling only too plainly that a disaster had occurred at the front. On accosting some of the fugitives, they assured me that the army was broken up, in full retreat, and that all was lost; all this with a manner true to that peculiar indifference that takes possession of panic-stricken men. I was greatly disturbed by the sight, but at once sent word to Colonel Edwards, commanding the brigade in Winchester, to stretch his troops across the valley, near Mill Creek, and stop all fugitives, directing also that the transportation be passed through and parked on the north side of the town.

As I continued at a walk a few hundred yards farther, thinking all the time of Longstreet’s telegram to Early, ‘Be ready when I join you, and we will crush Sheridan,’ I was fixing in my mind what I should do. My first thought was to stop the army in the suburbs of Winchester as it came back, form a new line, and fight there; but as the situation was more maturely considered a better conception prevailed. I was sure the troops had confidence in me, for heretofore we had been successful; and as at other times they had seen me present at the slightest sign of trouble or distress, I felt that I ought to try now to restore their broken ranks, or, failing in that, to share their fate because of what they had done hitherto.

About this time Colonel Wood, my chief commissary, arrived from the front and gave me fuller intelligence, reporting that everything was gone, my headquarters captured, and the troops dispersed. When I heard this I took two of my aides-de-camp, Major George A. Forsyth and Captain Joseph O’Keefe, and with twenty men from the escort started for the front, at the same time directing Colonel James W. Forsyth and Colonels Alexander and Thom to remain behind and do what they could to stop the runaways.

For a short distance I traveled on the road, but soon found it so blocked with wagons and wounded men that my progress was impeded, and I was forced to take to the adjoining fields to make haste. When most of the wagons and wounded were past I returned to the road, which was thickly lined with unhurt men, who, having got far enough to the rear to be out of danger, had halted without any organization, and begun cooking coffee, but when they saw me they abandoned their coffee, threw up their hats, shouldered their muskets, and as I passed along turned to follow with enthusiasm and cheers. To acknowledge this exhibition of feeling I took off my hat, and with Forsyth and O’Keefe rode some distance in advance of my escort, while every mounted officer who saw me galloped out on either side of the pike to tell the men at a distance that I had come back. In this way the news was spread to the stragglers off the road, when they, too, turned their faces to the front and marched toward the enemy, changing in a moment from the depths of depression to the extreme of enthusiasm. I already knew that even in the ordinary condition of mind enthusiasm is a potent element with soldiers, but what I saw that day convinced me that if it can be excited from a state of despondency its power is almost irresistible. I said nothing except to remark, as I rode among those on the road: ‘If I had been with you this morning this disaster would not have happened. We must face the other way; we will go back and recover our camp.’

My first halt was made just north of Newtown, where I met a chaplain digging his heels into the sides of his jaded horse, and making for the rear with all possible speed. I drew up for an instant, and inquired of him how matters were going at the front. He replied, ‘Everything is lost; but all will be right when you get there’; yet notwithstanding this expression of confidence in me, the parson at once resumed his breathless pace to the rear. At Newtown I was obliged to make a circuit to the left, to get round the village. I could not pass through it, the streets were so crowded, but meeting on this detour Major McKinley, of Crook’s staff, he spread the news of my return through the motley throng there.

According to Grant, “When Sheridan got to the front he found Getty and Custer still holding their ground firmly between the Confederates and our retreating troops.”

Everything in the rear was now ordered up. Sheridan at once proceeded to intrench [sic] his position; and he awaited an assault from the enemy. This was made with vigor, and was directed principally against Emory’s corps [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers], which had sustained the principal loss in the first attack. By one o’clock the attack was repulsed. Early was so badly damaged that he seemed disinclined to make another attack, but went to work to intrench [sic] himself with a view to holding the position he had already gained….

Sheridan Rallying His Troops, Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

What Sheridan encountered as he approached Newtown and the Valley pike from the south made him urge Rienzi on:

I saw about three-fourths of a mile west of the pike a body of troops, which proved to be Rickett’s and Wheaton’s divisions of the Sixth Corps, and then learned that the Nineteenth Corps [to which the 47th Pennsylvania had been assigned] had halted a little to the right and rear of these; but I did not stop, desiring to get to the extreme front. Continuing on parallel with the pike, about midway between Newtown and Middletown I crossed to the west of it, and a little later came up in rear of Getty’s division of the Sixth Corps. When I arrived, this division and the cavalry were the only troops in the presence of and resisting the enemy; they were apparently acting as a rear guard at a point about three miles north of the line we held at Cedar Creek when the battle began. General Torbert was the first officer to meet me, saying as he rode up, ‘My God! I am glad you’ve come.’ Getty’s division, when I found it, was about a mile north of Middleton, posted on the reverse slope of some slightly rising ground, holding a barricade made with fence-rails, and skirmishing slightly with the enemy’s pickets. Jumping my horse over the line of rails, I rode to the crest of the elevation, and there taking off my hat, the men rose up from behind their barricade with cheers of recognition. An officer of the Vermont brigade, Colonel A. S. Tracy, rode out to the front, and joining me, informed me that General Louis A. Grant was in command there, the regular division commander General Getty, having taken charge of the Sixth Corps in place of Ricketts, wounded early in the action, while temporarily commanding the corps. I then turned back to the rear of Getty’s division, and as I came behind it, a line of regimental flags rose up out of the ground, as it seemed, to welcome me. They were mostly the colors of Crook’s troops, who had been stampeded and scattered in the surprise of the morning. The color-bearers, having withstood the panic, had formed behind the troops of Getty. The line with the colors was largely composed of officers, among whom I recognized Colonel R. B. Hayes, since president of the United States, one of the brigade commanders. At the close of this incident I crossed the little narrow valley, or depression, in rear of Getty’s line, and dismounting on the opposite crest, established that point as my headquarters. In a few minutes some of my staff joined me, and the first directions I gave were to have the Nineteenth Corps [to which the 47th Pennsylvania was attached] and the two divisions of Wright’s corps brought to the front, so they could be formed on Getty’s division prolonged to the right; for I had already decided to attack the enemy from that line as soon as I could get matters in shape to take the offensive. Crook met me at this time, and strongly favored my idea of attacking, but said, however, that most of his troops were gone. General Wright came up a little later, when I saw that he was wounded, a ball having grazed the point of his chin so as to draw the blood plentifully.

Wright gave me a hurried account of the day’s events, and when told that we would fight the enemy on the line which Getty and the cavalry were holding, and that he must go himself and send all his staff to bring up the troops, he zealously fell in with the scheme; and it was then that the Nineteenth Corps [including the 47th Pennsylvania] and two divisions of the Sixth were ordered to the front from where they had been halted to the right and rear of Getty.

After this conversation I rode to the east of the Valley pike and to the left of Getty’s division, to a point from which I could obtain a good view of the front, in the mean time [sic] sending Major Forsyth to communicate with Colonel Lowell (who occupied a position close in toward the suburbs of Middletown and directly in front of Getty’s left) to learn whether he could hold on there. Lowell replied that he could. I then ordered Custer’s division back to the right flank, and returning to the place where my headquarters had been established I met near them Rickett’s division under General Kiefer and General Frank Wheaton’s division, both marching to the front. When the men of these divisions saw me they began cheering and took up the double quick to the front, while I turned back toward Getty’s line to point out where these returning troops should be place. Having done this, I ordered General Wright to resume command of the Sixth Corps, and Getty, who was temporarily in charge of it, to take command of his own division. A little later the Nineteenth Corps [including the 47th Pennsylvania] came up and was posted between the right of the Sixth Corps and Middle Marsh Brook.

All this had consumed a great deal of time, and I concluded to visit again the point to the east of the Valley pike, from where I had first observed the enemy, to see what he was doing. Arrived there, I could plainly seem him getting ready for attack, and Major Forsyth now suggested that it would be well to ride along the line of battle before the enemy assailed us, for although the troops had learned of my return, but few of them had seen me. Following his suggestion I started in behind the men, but when a few paces had been taken I crossed to the front and, hat in hand, passed along the entire length of the infantry line; and it is from this circumstance that many of the officers and men who then received me with such heartiness have since supposed that that was my first appearance on the field. But at least two hours had elapsed since I reached the ground, for it was after mid-day when this incident of riding down the front took place, and I arrived not later, certainly, than half-past 10 o’clock.

After re-arranging the line and preparing to attack I returned again to observe the Confederates, who shortly began to advance on us. The attacking columns did not cover my entire front, and it appeared that their onset would be mainly directed against the Nineteenth Corps [including the 47th Pennsylvania], so, fearing that they might be too strong for Emory on account of his depleted condition (many of his men not having had time to get up from the rear), and Getty’s division being free from assault, I transferred a part of it from the extreme left to the support of the Nineteenth Corps. The assault was quickly repulsed by Emory, however, and as the enemy fell back Getty’s troops were returned to their original place. This repulse of the Confederates made me feel pretty safe from further offensive operations on their part, and I now decided to suspend the fighting till my thin ranks were further strengthened by the men who were continually coming up from the rear, and particularly till Crook’s troops could be assembled on the extreme left.

In consequence of the despatch [sic] already mentioned, ‘Be ready when I join you, and we will crush Sheridan,’ since learned to have been fictitious, I had been supposing all day that Longstreet’s troops were present, but as no definite intelligence on this point had been gathered, I concluded, in the lull that now occurred, to ascertain something positive regarding Longstreet; and Merritt having been transferred to our left in the morning, I directed him to attack an exposed battery then at the edge of Middletown, and capture some prisoners. Merritt soon did this work effectually, concealing his intention till his troops got close in to the enemy, and then by a quick dash gobbling up a number of Confederates. When the prisoners were brought in, I learned from them that the only troops of Longstreet’s in the fight were of Kershaw’s division, which had rejoined Early at Brown’s Gap in the latter part of September, and that the rest of Longstreet’s corps was not on the field. The receipt of this information entirely cleared the way for me to take the offensive, but on the heels of it came information that Longstreet was marching by the Front Royal pike to strike my rear at Winchester, driving Powell’s cavalry in as he advanced. This renewed my uneasiness, and caused me to delay the general attack till after assurances came from Powell, denying utterly the reports as to Longstreet, and confirming the statements of the prisoners.

Launching another advance sometime mid-afternoon during which Sheridan “sent his cavalry by both flanks, and they penetrated to the enemy’s rear,” Grant added:

The contest was close for a time, but at length the left of the enemy broke, and disintegration along the whole line soon followed. Early tried to rally his men, but they were followed so closely that they had to give way very quickly every time they attempted to make a stand. Our cavalry, having pushed on and got in the rear of the Confederates, captured twenty-four pieces of artillery, besides retaking what had been lost in the morning. This victory pretty much closed the campaign in the Valley of Virginia. All the Confederate troops were sent back to Richmond with the exception of one division of infantry and a little cavalry. Wright’s corps was ordered back to the Army of the Potomac, and two other divisions were withdrawn from the valley. Early had lost more men in killed, wounded and captured in the valley than Sheridan had commanded from first to last.

The High Price of Valor

Headstone of Sergeant William Pyers, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Company C, Winchester National Cemetery, Virginia; he was killed in the fighting at the Cooley Farm during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (courtesy of Randy Fletcher, 2014).

But it was an extremely costly engagement for Pennsylvania’s native sons. The 47th experienced a total of one hundred and seventy-six casualties during the Battle of Cedar Creek alone, including Sergeants John Bartlow and William Pyers, and Privates James Brown (a carpenter), Jasper B. Gardner (a railroad conductor), George W. Keiser (an eighteen-year-old farmer), Joseph Smith, John E. Will, and Theodore Kiehl—all dead.

Most of those deceased heroes were simply described in the U.S. Army’s death ledger for 1864 as “killed in action.” Many were initially buried near where they fell and then later exhumed and reinterred at the Winchester National Cemetery in Winchester, Virginia, during the federal government’s large-scale effort to properly bury Union Army soldiers at national cemeteries.

In recounting the events of that terrible day in a letter later sent to the Sunbury American, Corporal Henry Wharton wrote, “This victory was, to us, of company C, dearly brought, and will bring with it sorrow to more than one Sunbury family.”

Soldiering On

Ordered to move from their encampment near Cedar Creek, Private Joseph B. Gray and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched to Camp Russell, a newly-erected, temporary Union Army installation that was located south of Winchester, just west of Stephens City, on grounds that were adjacent to the Opequon Creek. Housed here from November through 20 December 1864, they remained attached to the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah.

Five days before Christmas, he and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians were on the move again — this time, marching through a snowstorm to reach Camp Fairview, which was located just outside of Charlestown, West Virginia. Following their arrival, they were assigned to guard and outpost duties.

1865 — 1866

Still stationed at Camp Fairview as the old year gave way to the new, Private Joseph B. Gray and other members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry continued to help fulfill the directive of Major-General Sheridan that the Army of the Shenandoah search out and eliminate the ongoing threat posed by Confederate States guerrilla soldiers who had been attacking federal troops, railroad systems and supply lines throughout Virginia and West Virginia.

This was not “easy duty” as some historians and Civil War enthusiasts have claimed but critically important because it kept vital supply lines open for the Union Army, as a whole, as it battled to finally bring the American Civil War to a close with the surrender of General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army at Appomattox Court House on 9 April 1865.

In point of fact, it proved to be a dangerous time for 47th Pennsylvanians, as evidenced by regimental casualty reports, which noted that several members of the 47th Pennsylvania were wounded or killed by Confederate guerrillas.

Assigned in February 1865 to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade, Army of the Shenandoah, the regiment was in an “improved condition and general good health,” according to a report penned at the end of that month by Regimental Chaplain William DeWitt Clinton Rodrock to his superiors.

A large influx of recruits has materially increased our numbers; making our present aggregate 954 men, including 35 commissioned officers.

The number of sick in the Reg. is 22; all of which are transient cases, and no deaths have occurred during the month.

Whilst in a moral and religious point of view there is still a wide margin for amendment and improvement; it is nevertheless gratifying to state that all practicable and available means are employed for the promotion of the spiritual and physical welfare of the command.

The next month, Chaplain Rodrock described the regiment’s condition as “favorable and improved,” adding:

In a military sense it has greatly improved in efficiency and strength. By daily drill and a constant accession of recruits, these desirable objects have been attained. The entire strength of the Reg. rank and file is now 1019 men.

Its sanitary condition is all that can be desired. But 26 are on the sick list, and these are only transient cases. We have now our full number of Surgeons, – all efficient and faithful officers.

We have lost none by natural death. Two of our men were wounded by guerillas, while on duty at their Post. From the effects of which one died on the same day of the sad occurrence. He was buried yesterday with appropriate ceremonies. All honor to the heroic dead.

Sometime around this period, C Company’s twice-wounded Captain Daniel Oyster was authorized to take furlough; taking time out from visiting his family in Sunbury, he picked up the regiment’s Second State Colors — a replacement for the regiment’s very tattered, original battle flag. He later presented it to the regiment when he returned to duty.

Another New Mission, Another March

According to The Lehigh Register, as the end of March 1865 loomed, “The command was ordered to proceed up the valley to intercept the enemy’s troops, should any succeed in making their escape in that direction.” By 4 April 1865, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had made their way back to Winchester, Virginia and were headed for Kernstown. Five days later, they received word that Lee surrendered the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia to Union General Ulysses S. Grant.

In a letter penned to the Sunbury American on 12 April 1864, 47th Pennsylvanian Henry Wharton, described the celebration that took place, adding that Union Army operations in Virginia were still continuing in order to ensure that the Confederate surrender would hold:

Letter from the Sunbury Guards

CAMP NEAR SUMMIT POINT, Va.,

April 12, 1865Since yesterday a week we have been on the move, going as far as three miles beyond Winchester. There we halted for three days, waiting for the return or news from Torbett’s cavalry who had gone on a reconnoisance [sic] up to the valley. They returned, reporting they were as far up as Mt. Jackson, some sixty miles, and found nary an armed reb. The reason of our move was to be ready in case Lee moved against us, or to march on Lynchburg, if Lee reached that point, so that we could aid in surrounding him and [his] army, and with Sheridan and Mead capture the whole party. Grant’s gallant boys saved us that march and bagged the whole crowd. Last Sunday night our camp was aroused by the loud road of artillery. Hearing so much good news of late, I stuck to my blanket, not caring to get up, for I suspected a salute, which it really was for the ‘unconditional surrender of Lee.’ The boys got wild over the news, shouting till they were hoarse, the loud huzzas [sic] echoing through the Valley, songs of ‘rally round the flag,’ &c., were sung, and above the noise of the ‘cannons opening roar,’ and confusion of camp, could be heard ‘Hail Columbia’ and Yankee Doodle played by our band. Other bands took it up and soon the whole army let loose, making ‘confusion worse confounded.’

The next morning we packed up, struck tents, marched away, and now we are within a short distance of our old quarters. – The war is about played out, and peace is clearly seen through the bright cloud that has taken the place of those that darkened the sky for the last four years. The question now with us is whether the veterans after Old Abe has matters fixed to his satisfaction, will have to stay ‘till the expiration of the three years, or be discharged as per agreement, at the ‘end of the war.’ If we are not discharged when hostilities cease, great injustice will be done.

The members of Co. ‘C,’ wishing to do honor to Lieut C. S. Beard, and show their appreciation of him as an officer and gentleman, presented him with a splendid sword, sash and belt. Lieut. Beard rose from the ranks, and as one of their number, the boys gave him this token of esteem.

A few nights ago, an aid [sic] on Gen. Torbett’s staff, with two more officers, attempted to pass a safe guard stationed at a house near Winchester. The guard halted the party, they rushed on, paying no attention to the challenge, when the sentinel charged bayonet, running the sharp steel through the abdomen of the aid [sic], wounding him so severely that he died in an hour. The guard did his duty as he was there for the protection of the inmates and their property, with instruction to let no one enter.

The boys are all well, and jubilant over the victories of Grant, and their own little Sheridan, and feel as though they would soon return to meet the loved ones at home, and receive a kind greeting from old friends, and do you believe me to be

Yours Fraternally,

H. D. W.

Two days later, that fragile peace was shattered when a Confederate loyalist fired the bullet that ended the life of President Abraham Lincoln.

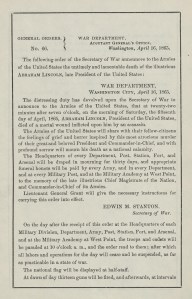

Broadside showing the text of General Orders, No. 66 issued by U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and Lieutenant-General Ulysses S. Grant on 16 April 1865 to inform Union Army troops about the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and provide instructions regarding the appropriate procedures for mourning (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain; click to enlarge).

On 16 April 1865, U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and Lieutenant-General Ulysses S. Grant issued General Orders, No. 66, confirming that President Abraham Lincoln had been murdered and informing all Union Army regiments about changes to their duties, effective immediately, in the wake of President Lincoln’s assassination. Those orders also explained to Union soldiers what the appropriate procedures were for mourning the president:

The distressing duty has devolved upon the Secretary of War to announce to the armies of the United States, that at twenty-two minutes after 7 o’clock, on the morning of Saturday, the 15th day of April, 1865, ABRAHAM LINCOLN, President of the United States, died of a mortal wound inflicted upon him by an assassin….

The Headquarters of every Department, Post, Station, Fort, and Arsenal will be draped in mourning for thirty days, and appropriate funeral honors will be paid by every Army, and in every Department, and at every Military Post, and at the Military Academy at West Point, to the memory of the late illustrious Chief Magistrate of the Nation and Commander-in-Chief of its Armies.

Lieutenant-General Grant will give the necessary instructions for carrying this order into effect….

On the day after the receipt of this order at the Headquarters of each Military Division, Department, Army, Post, Station, Fort, and Arsenal and at the Military Academy at West Point the troops and cadets will be paraded at 10 o’clock a. m. and the order read to them, after which all labors and operations for the day will cease and be suspended as far as practicable in a state of war.

The national flag will be displayed at half-staff.

At dawn of day thirteen guns will be fired, and afterwards at intervals of thirty minutes between the rising and setting sun a single gun, and at the close of the day a national salute of thirty-six guns.

The officers of the Armies of the United States will wear the badge of mourning on the left arm and on their swords and the colors of their commands and regiments will be put in mourning for the period of six months.

Spectators gather for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, beside the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half-staff following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Reassigned to defend the nation’s capital, Private Joseph B. Gray and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were stationed just outside of Washington, D.C., prepared to intercept any former Confederate soldiers or their sympathizing followers bent on wreaking more havoc in the nation’s capital.

Prohibited from attending President Lincoln’s funeral in Washington, D.C., because they were expected to remain on duty, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers joined with other Union troops in mourning him during a special, separate memorial service conducted for their brigade that same day. Officiated by the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental chaplain, the service enabled the men to voice their grief at losing their beloved former leader. Chaplain Rodrock later expressed the feelings of many 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers as he described Lincoln’s assassination as “a crime against God, against the Nation, against humanity and against liberty” and “the madness of Treason and murder!” Written as part of a report to his superiors on 30 April 1865, he added, “We have great duties in this crisis. And the first is to forget selfishness and passion and party, and look to the salvation of the Country.”

Letters penned by other 47th Pennsylvanians to family and friends back home during this period documented that C Company Drummer Samuel Hunter Pyers was given the honor of guarding the late president’s funeral train while other members of the regiment were involved in guarding the key conspirators in Lincoln’s assassination during the early days of their confinement at the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C.

On 11 May 1865, the 47th Pennsylvania’s First State Color was retired and replaced with the regiment’s Second State Color. Attached to Dwight’s Division, 2nd Brigade, U.S. Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers next flexed their muscles in an impressive show of the Union Army’s power and indomitable spirit during the Union’s Grand Review of the Armies, which was conducted in Washington, D.C. from 23-24 May 1865, under the watchful eyes of President Lincoln’s successor, President Andrew Johnson, and Lieutenant-General Grant.

Reconstruction Duties

Ruins of Charleston, South Carolina as seen from the Circular Church, 1865 (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

Assigned to provost (military police) and Reconstruction-related duties during their final phase of military service, Private Joseph B. Gray and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were sent on a final swing through America’s Deep South. Still attached to Dwight’s Division, they were initially stationed in Savannah, Georgia from 31 May to 4 June 1865, as part of the 3rd Brigade of the U.S. Army’s Department of the South.

Ordered to relieve the 165th New York Volunteers in July, they quartered in the former mansion of the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury in Charleston, South Carolina. Assigned to provost duty, they ensured the smooth operation of the local judicial system by providing guards for the area’s jails, facilitating operations of the courts and carrying out other civic governance tasks as needed.

Finally, on Christmas Day, 1865, the majority of the regiment, including Private Joseph B. Gray, mustered out for the last time at Charleston, South Carolina. Following a voyage home to New York by ship, the weary 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers were transported to Camp Cadwalader in Philadelphia, where they received their honorable discharge papers in early January 1866.

Last paid as of 30 June 1865, Private Gray’s clothing account was reported on regimental muster rolls as “Never Settled,” noting that he still owed the federal government five dollars and ninety-three cents for his uniform and six dollars for arms and accoutrements (per General Orders, No. 101, issued by the U.S. Office of the Adjutant General). He also owed three dollars to sutler W. H. Webb for supplies that he had purchased while in service to the nation.

In reality, he was not a debtor — because he was also still owed sixty of the one hundred and eighty-dollars that the federal government had promised to pay him when he enrolled for military service in 1864.

Return to Civilian Life

According to professional genealogist, Kathryn M. Doyle, during his tenure of military service, Joseph B. Gray had participated in “four cruising voyages, traveling fifteen thousand miles along the coast” of the United States. Following his honorable discharge from the military, he returned home to Juniata County, where he resumed life as a farmer.

In 1868, he married Martha A. McCullough (1846-1875), who was a daughter of Franklin County residents William McCullough (1797-1876) and Isabella (Morrow) McCullough. On 7 September 1869, they welcomed the birth of their first child — a son, James McCullough Gray (1869-1894).

* Note: Meanwhile, Joseph Berry Gray’s stepmother, Leah (Barton) Gray, was giving birth to two more children: Howard D. Gray (1866-1892), who was born on 23 August 1866, but who would also die early (at the age of twenty-five on 28 July 1892); and Jesse Franklin Gray (1869-1948), who was born in Perulack, Juniata County on 4 July 1869 and would later marry Susan May Flood (1870-1897) and become an associate judge in Union County, Pennsylvania.

During the winter of 1870, Joseph B. Gray’s brother, Thomas Gray, died from consumption (tuberculosis) in Lack Township on 2 February. Following funeral services, Thomas was laid to rest at the same cemetery where their mother had been buried (the Upper Tuscarora Presbyterian Cemetery in Waterloo, Juniata County).

By mid-July of that same year, a federal census enumerator was confirming that Joseph B. Gray was a laborer residing with his wife, Martha, and their son, James, in Noffsville, Tell Township, Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania. They were living at the home of Martha’s parents, shoemaker William McCullough and Isabella (Morrow) McCullough. The following year proved to be a joyful one with the birth of daughter Almeda Ellen Gray (1871-1959) in Waterloo, Juniata County on 25 March 1871. A second son, William Marshall Gray (1873-1902) was then born on 1 February 1873.

Sadly, Joseph B. Gray’s half-brother, Samuel B. Gray, then also died at an early age. Never married, he passed away while still in his early twenties on 21 August 1873, and was buried at the Upper Tuscarora Cemetery in Waterloo.

In 1874, Joseph B. Gray relocated with his wife and children to Shirleysburg in Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania. Sadly, while there, Joseph B. Gray’s wife, Martha A. (McCullough) Gray, widowed him while she was still just in her late twenties. Following her death in Shirleysburg in 1875, her remains were returned to Juniata County for burial at the Newton Hamilton Memorial Cemetery in Newton Hamilton.

Grief-stricken, Joseph B. Gray struggled to care for his young children, prompting his sister, Martha (Gray) Arnold to step in. (Raising his youngest son, William Marshall Gray, as her own, she would go on to supervise William’s education in the public schools of Juniata County and at the college in Shippensburg, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania.)

Meanwhile, Joseph B. Gray was trying to begin life anew — again — after returning home to Juniata County, where he worked as a farmer and as a civil servant who collected taxes from residents and business owners of Lack Township as early as the winter of 1878. Three years after his wife’s untimely death, he remarried, taking as his second wife, Jane Isabelle Fleming (1841-1925). A native of Shade Gap, Huntingdon County, she was a daughter of Huntingdon County natives James Fleming (1805-1884) and Elizabeth Matilda (Wilson) Fleming (1815-1873), and was known to family and friends as “Belle.”

Huntingdon, Pennsylvania, circa 1883 (William H. Egle, History of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 1883, public domain).

According to the Juniata Sentinel and Republican, Joseph B. Gray was still employed as a tax collector as of January 1880. By early February of that same year, however, he and his second wife, Belle, were residing with two of his children from his first marriage (James McCullough Gray and Almeda Ellen Gray) in Huntingdon County’s Germany Valley, where he and Belle welcomed the birth of their first child, Lloyd Alexander Gray (1880-1906) on 8 February 1880.

Per that year’s federal census, during which the Berry family was interviewed by a census enumerator in early June, he and his wife, Belle, were residing in Dublin Township, Huntingdon County with their three children: James, Almeda and Lloyd.

By 1890, he had returned to Mifflin County and had taken up farming in Wayne township. According to Welch, the farm owned and operated by Joseph B. Gray was located in the community of Newton Hamilton. Sometime during that same year, Joseph B. Gray’s daughter, Almeda, wed Emory Forest Bratton (1855-1940), who was a native of McVeytown in Mifflin County.

Tragedy then struck the Gray family again during the following two years when Joseph B. Gray’s half-brothers, George Washington Gray and Howard D. Gray, died, respectively, at the ages of thirty-five and twenty-five, on 29 August 1891 and 28 July 1892. A farmer, George W. Gray was subsequently buried at the Upper Tuscarora Presbyterian Cemetery in Waterloo; Howard Gray, still single, was then also buried there the following year.

Roughly three years later, Joseph B. Gray’s son, James McCullough Gray, passed away at the age of twenty-five in Newton Hamilton on 29 November 1894. Following funeral services, James was laid to rest at the Newton Hamilton Memorial Cemetery.

In 1898, Joseph B. Gray assumed responsibility for the management of his father’s two-hundred-acre farm, following his father’s death at the age of ninety in Beale Township, Juniata County on 27 October of that year. Under Joseph B. Gray’s watchful eye, the farm truly began to prosper. By early June of 1900, he was still working on that farm, where he resided with his wife, Belle, and sons, Lloyd and William, who were both enrolled in school. Also living with them while attending school was Joseph Gray’s niece, Annie Perl.

Sadly, the grim reaper claimed another of Joseph B. Gray’s children shortly thereafter. A student at Shippensburg State Normal School since 4 September 1900, William Marshall Gray had contracted typhoid fever shortly after his arrival at the college. On 22 September of that same year, he was transported to his father’s home in Wayne Township, where he was able to recover after roughly two months of treatment. Weakened by his battle with typhoid, however, William Gray then fell prey to the “White Death” (also known as consumption or tuberculosis), which caused him to gradually waste away. Realizing that his condition was precarious and desiring to spend his final months with the woman he considered to be his real mother — Martha (Gray) Arnold, the paternal aunt who had cared for him between 1875 and 1894 — William Gray had relocated to her home in Pyleton on 13 May 1902, but died there just ten days later on 23 May 1902. Just twenty-nine years, three months and twenty-three days old at the time of his passing, his remains were returned to the communuty of Newton Hamilton for burial at the Newton Hamilton Memorial Cemetery.

That same year (1902), Joseph B. Gray’s first-born child from his second marriage, Lloyd Alexander Gray, wed Illinois native Carolyn Nevin Hayes (1882-1970), who was a daughter of Robert A. Hayes (1847-1887) and Shippensburg, Pennsylvania native Annie Margaretta (Rankin) Hayes (1853-1927). Their wedding took place in Carlisle, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania on 10 December, and was officiated by the Rev. George Norcross. Roughly two years later, their son, Melvin Nevin Gray (1904-1982) was born. Lloyd A. Gray never had the chance to watch his son grow to manhood, however; a working inspector, Lloyd Gray contracted typhoid fever at the age of twenty-six in early April 1906 and died later that same month (on 23 April 1906) in Wilkinsburg, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. His remains were subsequently returned to Newton Hamilton for interment at the Newton Hamilton Memorial Cemetery (on 26 April).

Later that same year (1906), Joseph B. Gray’s younger half-sister, Alice Christian (Gray) Beckenbaugh, widowed her husband, James B. Beckenbaugh, when she succumbed to pulmonary phthisis, a wasting-away complication which frequently developed in children and adults who were battling tuberculosis. Following her death at the age of forty-two in Wayne Township, Mifflin County on 6 June, she was also buried at that county’s Newton Hamilton Memorial Cemetery.

A year later, Joseph B. Gray’s older sister, Martha Dillon (Gray) Arnold, was also gone. Also battling pulmonary tuberculosis, she had ben ailing since January of 1907. She then contracted “La Grippe” (the flu) in early July, which ended her life on 29 July 1907. Like many of her other family members, she still rests at the Upper Tuscarora Presbyterian Cemetery in Warerloo.

A Democrat, politically, Joseph Berry Gray remained active with the Grand Army of the Republic throughout his post-war life, as a member of the G.A.R.’s Surgeon Charles Bower Post (No. 457). He also served as a justice of the peace and as a school director.

Still residing with his wife, Belle, in Shirleysburg as of early May 1910, Joseph B. Gray was now retired and living off his “own income.” That summer, he and his wife traveled west in order to visit several family members. While they were away, the Mount Union Times published a report about the trip that was penned by Joseph B. Gray:

Rinard, Ill., July 16, 1910:

EDITORS TIMES:–Thinking your readers might be interested in an account of our trip towards the setting sun, which we had been contemplating for some time, I will endeavor from my memory to give you a brief sketch of the same, as I did not keep a diary.

On Saturday May 21st, Mrs. Gray and I shook the dust of Shirleysburg off our feet and boarded the 3:25 train for Mt. Union where we arrived in due time for the 4:35 train on the P. R. R. Arriving in Altoona we found my brother James and daughter, who had preceded us several days at my son’s-in-law, E. F. Bratton’s. While there, we took in quite a number of the sights of the Mountain City and in addition we took in the Ringling Bros. show. I observed some of my Shirleysburg neighbors. We also had the pleasure of participating in the Memorial Day exercises which were quite elaborate. A beautiful monument has been erected by that city on the eminence of the cemetery to the memory of our fallen heroes who rest there, and to those who may yet find their resting place there. In the circle around the monument I noticed on the markers the names of Geo. W. Miller Co. A. 49th P. V., W. Y. Gray Co. B. 49th P. V., Elijah Long 28th P. V. The oration was delivered by Rev. Pickers of Altoona a former preacher in the Juniata field, well known by a number of Shirley and Mt. Union people.

On May 31st we left Altoona for Johnstown to visit our cousin, Seibert Harris, brother of the late Wm. Harris of Concord, Pa., who was a brother-in-law of your townsman Frank Harrison. While there, Mrs. Harris took our party up the incline to the eminence that overlooks the city. While viewing the city, in my imagination, I could see the elements in their fury carrying to destruction everything in its path. On this eminence there are the finest modern residences it has ever been my lot to observe, some of them have the ancient large stone chimneys and large fireplaces.

Next we visited that eminence on which is buried the unknown dead of the flood of 1889. It makes one sad to look at the blank markers without any lettering on them. The Cemetery is enclosed with a stone fence about five feet high and the enclosure contains, I suppose 25 acres. A large number of the “old boys” are buried there.

June 2nd we left for Wilkinsburg, Pa., where my daughter-in-law lives, Mrs. J. H. McCullock. Spending a few days there we proceeded to Allegheny to my sister’s Mrs. W. J. Eberts. On June 7th at 9:25 p.m., we again set our faces westward on the B. & O. R. R. for Rinard, Ill., where we are at present located at my brother John’s, who resides 2 1/2 miles west of Rinard, on a beautiful prairie farm; we arrived here June 8th.

This is certainly a beautiful country. Prairies as far as you can see are interspersed with tracts of timberland sufficient for fuel, some farms having as much as 30 acres to which they turn their cattle to pasture. But they have abundance of pasture land besides these.

The principal source of income is from stock and red top seed.

The wheat crop in this section is small but little was put to wheat last fall on account of the chinch bug the past few years being so destructive. The hay and oats crop is large. The corn crop is also promising if the weather be favorable. A great source of income here is from poultry. Few farmers think of having less than from 200 to 500 hens. My brother realized last year net from 300 hens over $300.

Rinard is a small town not over 200 population, 2 general stores yet the 2 merchants have shipped as high as 500 crates of eggs a week. What do you think of this farmers of Penna? Awake to the fact that you have no stock on your farms that bring you the margin your poultry will if you give it the proper attention.

My brother and daughter left for Arcola, Ill., this week. We will meet last of this month in Delphi, Ind., to visit our only aunt, my mother’s sister. From there we will set our faces eastward visiting friends in Ohio and Pittsburg on our return. I will bring my article to a close lest I weary your readers. We have all been in fine health and have had an enjoyable time all along the way.

A few words more in regard to egg traffic. My nephew just informed me that he knew one farmer to bring $90 worth to Renard in one load and received cash for them. We have been here five weeks and in that time my brother has marketed two hundred and forty doz and has 42 doz on hand.

I hope this article may encourage my neighbor farmers to enter more extensively into the poultry business. No danger of it being over done, it can be made profitable at a less figure than they now receive. With kind regards to one and all.

I am respectfully yours,

J. B. Gray.

Unidentified visitors at the entrance to the Methodist Training Camp, Newton Hamilton, Pennsylvania, circa mid to late 1920s (public domain).

By the early 1920s, Joseph B. Gray and his wife were still “empty nesters” who frequently spent their summers in Shirleysburg, but wintered with their daughter at her home at the Methodist Training Camp in Newton Hamilton. A ruling elder in the Presbyterian Church for many years, he was compelled by his health to retire from many of his spiritual activities by 1915. Four years later, his second wife, Belle, fell down the stairs of their home and lacerated her face.

By September of 1925, newspapers were reporting that he had “been in Altoona under the care of a physician for some time,” while his wife, Belle, was residing at the home of their daughter, Almeda (Gray) Bratton, at the Methodist Training Camp in Newton Hamilton. Following Belle’s death there at the age of eighty-three, on 3 December of that year, she was also interred at the Newton Hamilton Memorial Cemetery. According to her obituary in the Mount Union Times:

Because of the infirmities of both Mrs. Gray and her husband, the Gray home in Shirleysburg was broken up in the early autumn and sale made of their household furnishings. The event was a great grief to Mrs. Gray and she declined rapidly since….

Funeral services were held from the Bratton home, Newton Hamilton, Saturday afternoon at 2 o’clock [12 December 1925], in charge of Rev. C. H. Goshorn, pastor of the Presbyterian church of Newton Hamilton, assisted by Rev. C. G. Weimer of the Methodist church, that place. Burial followed in the Memorial cemetery, Newton Hamilton, directed by A. J. Barben.

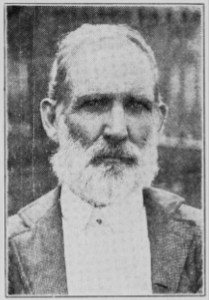

Illness, Death and Interment

Joseph Berry Gray’s gravestone, Newton Hamilton Memorial Cemetery, Newton Hamilton, Pennsylvania, 1910 (used with permission, courtesy of Mona Anderson).

Ailing and frail during his final years, due both to the chronic rheumatism which he had developed during his sevice with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers during the American Civil War, and to the valvular heart impairment and senility that he had developed, post-war, Joseph Berry Gray also spent his own final years at the home of his daughter, Almeda (Gray) Bratton, ultimately becoming a beloved figure as Newton Hamilton’s last surviving Civil War veteran.

He died there at the age of eighty-four at 2 p.m. on 31 August 1927. Following funeral services, which were held at the home of his daughter at 1:30 p.m. on 2 September 1927, he was laid to rest at the Newton Hamilton Memorial Cemetery with military honors. The graveside services were conducted by members of the Grand Army of the Republic (George Kane Post) and the American Legion (Simpson Post).

What Happened to the Other Siblings of Joseph Berry Gray?

Joseph B. Gray’s brother, James Harris Gray, continued to reside in Juniata County, where he wed Margaret McWilliams circa 1866. Their son, Robert McWilliams Gray (1867-1955) was born on 30 December 1867. Nearly two years later, they welcomed daughter Bessie (1869-1928) to the world on 29 November 1869. (Robert would later go on to wed Flora Flood, while Bessie would later go on to marry John P. Bock.) James Harris Gray supported his family by farming, according to federal census records from both 1870 and 1880. By 1900, he and his wife were still residing in Lack Township, where he continued to farm his land. Also living with them was their daughter, Bessie. Ailing from heart disease, he died from mitral regurgitation in Metal Township, Franklin County, Pennsylvania on 27 September 1915. Following funeral services, he was laid to rest at the East Waterford Cemetery in Tuscarora Township, Juniata County.

A turn-of-the-century sketch of the Yamhill River illustrated how rural Lafayette, Oregon still was after William Gray’s death (Morning Oregonian, 22 September 1900, public domain).

Unlike Joseph B. Gray, his brother, William S. Gray, opted to leave Pennsylvania after the war and then marry. Migrating west to America’s heartland, he wed Tennessee native Mary Jane Gilbert in Cass County, Indiana on 30 January 1866 and then relocated with his wife to Missouri, where he became a farmer. Their daughter, Laura Ellen (1867-1922), was born on 6 January 1867. By 1870, the trio resided in the town of Clinton in Big Creek Township, Henry County, Missouri.

Sometime after that year’s federal census, however, he and his family were on the move again — this time to Oregon, where a second daughter, Florence Martha, was born in the Village of Lafayette in Yamhill County on 1 April 1871. (Martha would later go on to marry Joseph Hammond Heald.) By 1880, they were all still living in Lafayette, but their happiness lasted barely a decade. Following William Gray’s death at the age of fifty-four in the city of Portland, Multnomah County, Oregon on 27 October, 1891, he was laid to rest at that city’s Multnomah Park Cemetery.

Meanwhile, Joseph B. Gray’s brother, John Gray, was undertaking his own migration and marriage. By 1868, he was a resident of the community of Rinard in Wayne County, Illinois, and was the husband of Mary Elizabeth (Cook) Gray (1852-1920), a native of Rinard who was a daughter of Lorenzo Payne Cook and Louisa (Price) Cook. Their first child, Martha Permelia Gray (1870-1893), was born in Wayne County on 4 March 1870, followed by the subsequent Wayne County births of: Lillian Louisa Gray (1872-1957), who was born on 29 August 1872 and later went on to marry John Henry Croughan (1869-1938) in 1896; Lorenzo Pearley Gray (1876-1936), who was born on 5 June 1876 and later wed Myrtle E. Moore (1883-1966); William Edgar Gray (1879-1879), who was born on 21 April 1879, but died at the age of three months on 21 July of that same year; Arminta May Gray (1881-1963), who was born on 12 May 1881 and later went on to marry Theodore Monroe Cunningham (1877-1966); James Earl Gray (1883-1959), who was born in Rinard, Wayne County on 2 December 1883 and later wed Nellie Mae Van Fossan (1887-1949) in 1912; and Elsie Beulah Gray (1887-1900), who was born on 5 August 1887, but died at the age of thirteen, on 8 April 1900.

Still residing in Rinard, Illinois as of 1910, John S. Gray welcomed his brother, Joseph B. Gray, for a visit during the summer that year. Joining Joseph on that visit was Joseph’s wife. In a subsequent travelogue about his trip that was published by the Mount Union Times newspaper in Mount Union, Pennsylvania, Joseph noted that his brother lived on “a beautiful prairie farm” that was located roughly two and one-half miles west of Rinard, where his brother operated a successful poultry business. Two years later, John Gray and his wife then traveled east to visit Joseph and his family in Shirleysburg, Pennsylvania in November 1912. Following a long and productive life, John S. Gray died at the age of eighty-two in Wayne County on 6 July 1921, and was laid to rest at the Bunker Cemetery in Rinard.

Joseph B. Gray’s brother, Alexander Cooper Gray, did opt to stay in Pennsylvania. Following his marriage to Sarah Pilgrim McCullough sometime during the mid-1860s, he welcomed the birth of a son, Jason Robinson Gray (1867-1920), who was born on 20 March 1867, later wed Elsie Lenore Curry (1877-1902) in 1892 and went on to work as a member of the wrecking crew for the Pennsylvania Railroad Company (also known as the “Pennsy” or “P. R.R.”). Settled with his wife and son in Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania by the fall of 1870, Alexander C. Gray subsequently welcomed the births of: Araminta Melinda Gray (1870-1967), who was born in Shirley Township, Huntingdon County on 9 November 1870 and was known to family and friends as “Mintie,” and who later wed John Harry Naylor (1870-1929) in 1892; Millie Malcena Gray (1874-1954), who was born in Shirleysburg, Huntingdon County on 19 June 1874 and later wed Ira Samuel Crouse circa 1892; Charles Emerson Gray (1878-1963), who was born in Shirleysburg on 15 June 1878 and later wed Mary Ethel Foster (1892-1945); and Edmund Campbell Gray (1886-1963), who was born in Shirleysburg on 2 December 1886 and later wed Helen A. Farnworth (1888-1962). By 1897, Alexander Cooper Gray, had relocated to McKean County, Pennsylvania. He died at the age of seventy-one at the home of his daughter, Araminta (Gray) Naylor, in Mount Jewett, McKean County on 8 December 1917. His remains were subsequently transported to Mifflin County for interment at the Newton Hamilton Memorial Cemetery.

Having wed William Jacob Eberts sometime during the early 1870s, Joseph B. Gray’s half-sister, Nancy Elizabeth (Gray) Eberts, settled with her husband in Tell Township, Huntingdon County, where their first child, Nettie M. Eberts (1874-1966), was born on 7 April 1874. (Nettie would later go on to marry Edwin D. Beck in 1891.) Five more children soon followed: Joseph Edgar Eberts (1877-1964), who was born in Juniata County, Pennsylvania on 20 February 1877 and later wed Wilhelmina Amelia Augusta Meisold (1888-1970); George W. Eberts (1880-1964), who was born in Blairs Mills, Huntingdon County on 24 May 1880) and later wed Emma Helen Yonker (1881-1971) in 1901; Samuel Calvin Eberts (1883-1930), who was born in Tell Township on 15 February 1883, and later served as a private in the United States Army; Leah Eberts (1885-1950), who was born on 12 April 1885 and later wed Henry W. Petersen (1880-1948); and Lavina Elizabeth Eberts (1894-1973), who was born in Johnsonburg, Elk County, Pennsylvania on 9 February 1894 and later wed Robert Ross Bassett (1894-1933) in 1917. Ailing with heart disease in her later years, Nancy Elizabeth (Gray) Eberts was three months shy of her eighty-fifth birthday when she passed away in Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania on 28 March 1938. Her remains were subsequently transported to Mifflin County for burial at the Newton Hamilton Memorial Cemetery.

Having wed Hannah Jane Varner sometime during the 1870s, Joseph B. Gray’s half-brother, Harvey Baxter Gray, welcomed the birth of his first child, Cora L. Gray (1880-1933), who was born on 8 July 1880 and would later wed Thomas Phillip Flood (1877-1962). Their second daughter, Mary Alice Gray (1881-1968), who would later go on to marry Turbett Lynn Eaton (1875-1962), was born in Perulack, Juniata County on 2 July 1881. More children soon followed at their Juniata County home: Rebecca M. Gray (1883-1911), who was born on 11 March 1883 and later wed James Melvin Klinger (1879-1958); Anna Grace Gray (1885-1937), who was born on 26 January 1885 and later wed Edward Washington Burdge (1878-1953) in 1902; Bessie Ada Gray (1887-1969), who was born on 26 February 1887 and later wed Oscar Banks Wolfgang (1875-1942); and Josephine Gray (1890-1916), who was born on 30 April 1890 and later wed Frank M. Reeder (1880-1971). Preceded in death in 1909 by his first wife, who had been known to family and friends as “Jennie,” Harvey Baxter Gray remarried on 15 November 1910, taking as his second wife, Amanda (Latherow) McMullen (1855-1951), a native of Huntingdon County who was a widow with two children. He subsequently preceded his second wife in death, passing away on his birthday (19 September) in 1930 at the age of seventy-six, in Lack Township, Juniata County. Following funeral services, he was interred at the Upper Tuscarora Church Cemetery in Waterloo.

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument and the Mifflin County Courthouse, Lewistown, Pennsylvania, circa late 1890s (public domain).

Meanwhile, Joseph B. Gray’s half-brother, Calvin B. Gray, left Pennsylvania on 23 February 1886 to accept a farming job in Bucyrus, Ohio “for the summer,” according to the Juniata Sentinel and Republican newspaper. Joining him on the trip was T. Vaughen. Having subsequently returned home to Juniata County, he wed Mary E. Crouse on 29 December 1887, and then welcomed the birth with her of one son, Guy E. Gray (1891-1978), who was born on 27 September 1891. Sometime around the turn of the century, Calvin relocated with his wife and son to the community of Lewistown in Mifflin County, Pennsylvania, where he was employed by the Lewistown and Reedsville Trolley Company until his retirement in 1929. In his spare time, he was active in civic affairs as a Mason (Lewistown Lodge, No. 203) and as a volunteer firefighter who helped to found Lewistown’s City Hook and Ladder Company. He also represented Lewistown’s Fifth Ward for one term as an elected member of the city council. President of City Hook and Ladder Company No. 4 in 1920, he was honored by his community in December of that year for personally raising money from Lewistown residents to pay down more than half of the volunteer fire company’s seven thousand dollar debt. That same year, The News of Newport, Perry County, Pennsylvania described him as follows:

Calvin Gray of Lewistown is one of the active and prominent firemen of his city. He is a charter memberof the City Hook & Ladder Fire Company, organized on September 25, 1904, with thirty-four members. He was the second Fire Chief of his fire company, when fire hose carts were still pulled by hand to fires. During the past few months, Mr. Gray personally secured by solicitation $3956.90 of more than half of the total cost of two new fire auto trucks recently bought by Mr. Gray’s company, to replace the hand power drawn hose carts. He has not only distinguished himself as a volunteer fireman, but also as a local trolley man. On next June 3, it will be 21 years since he entered the employ of the Lewistown & Reedsville Electric Railway Company. He came here from Altoona where he was in trolley service eight months. He is generally recognized as an exceptionally careful trolley motorman, never having had any connection with a fatal accident while operating trolley cars during his more than 20 years of experience. His right arm was three times broken in its forearm, near the same point, two times both bones being broken and once only one bone being fractured. August 30, 1904, he fell off a trolley car; November 24, 1905 he was in a trolley wreck and February 21, 1909, he slipped upon ice, causing a fracture of the same forearm each time. He is Ex-city councilman of Mt. Jewett, McKean County, and of Lewistown borough. He served three years as treasurer of Mt. Jewett borough council….

Ailing from heart disease and diabetes during his later years, Calvin Gray endured the amputation of one of his legs, from which “he never quite recovered,” according to his obituary. Following his death at the age of seventy-two in Lewistown on 15 October 1930, he was buried at that city’s St. Mark’s Cemetery.