With Gratitude:

This biography is sponsored by Amy (Lowers) Maurer and her family, proud descendants of H. B. Robinson. The Maurer family’s generous financial and in-kind support have helped the founder of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story to research, preserve and share key details about H. B. Robinson’s life before, during and after the American Civil War.

Alternate Spellings of Surname: Robison, Robinson

Alternate Given Names: H. B., Brad, Brady, Horace

Brilliant. Well-read, well-educated and greatly respected by his army buddies, business colleagues and civic leaders. A problem solver with the soul of an adventurer.

His name was H. B. Robinson, and he was an underaged soldier who survived the American Civil War to return to school, earn a university degree in civil engineering and gain the trust of pioneering oil and gas industry executives across the United States, becoming a valuable advisor who oversaw the construction of multiple, first-of-their-kind, oil pipelines that changed America’s future forever.

Formative Years

Born as Horace Brady Robison in Academia, Juniata County, Pennsylvania on 22 March 1849, H. B. Robinson (alternate surname spelling: “Robison”) was a son of Mifflin County, Pennsylvania native John Albert Robison (1822-1884) and Pennsylvania native Sarah Ann (Armstrong) Robison (1819-1892), and the sibling of: Thomas Robison (1847-1901), who had been born in Academia in July 1847, was ordained as a minister in the Presbyterian Church in 1875, and then wed Ella T. Wilson in 1876; Mary Ellen Robison (1851-1851), who was born in Juniata County on 11 January 1851, but died in infancy on 18 June of that same year; Clara Robison (1851-1945), who was also born in Juniata County on 11 January 1851, but survived and went on to wed New Jersey native Emley J. Wilbur (1852-1936); John Albert Robison, Jr. (1853-1899), who was born in Milford Township on 1 February 1853 and later wed Margaret Azele Brown (1857-1947); Mary Genevieve Robison (1856-1936), who was born on 2 March 1856 and later wed Charles H. Burtis (1858-1910); Sarah Grace Armstrong Robison (1858-1924), who was born on 16 March 1858; Katharine Maude Florence Robison (1861-1922), who was born in Juniata County on 27 April 1861 and later wed Josiah Holcomb Dean (1861-1925); and Jessie Benton Robison (1863-1875), who was born in 1863 and was known to family and friends as “Benton.”

Descended from the Alexander Robison who had settled in Pennsylvania’s Tuscarora Valley during the mid-1700s, H. B. Robinson and his siblings were raised on the Robison family’s farm in Milford Township, Juniata County. The spelling of their family surname was spelled as “Robison” on some federal census records and gravestones, but as “Robinson” on others.

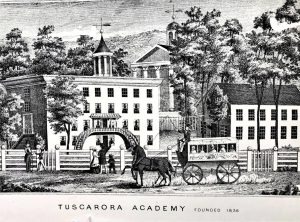

Raised and educated at the highly regarded Tuscarora Academy in Academia, H. B. Robinson and his siblings were given the inspiration they needed to become enthusiastic, lifelong learners.

By 1860, the federal census enumerator was documenting that their family’s partriarch, John A. Robinson, was the owner of personal property and real estate that was valued at twenty-two thousand dollars (the equivalent of roughly eighty-four thousand U.S. dollars in 2025). That year, the household included John Sr. and his wife, Sarah, as well as their children: Thomas A., Horace (who was listed on the federal census as “Orris B.” but ultimately came to be known by his initials “H. B.” for much of his lifetime), Clara, John A. Jr., Mary G., and Grace A. Also residing with the family were John’s mother, Catherine, who was described as a “Lady.” Thomas and H. B. were documented as being current students at that time, while Clara, John Jr. and Mary Genevieve were described as having attended school within the last year. Also residing with the family was sixty-six-year-old housekeeper Elizabeth Swiler and three-year-old Parker Brant.

“The Union Is Dissolved” (broadside announcement of South Carolina’s secession from the United States, Charleston Mercury, 20 December 1860, U.S. Library of Congress and National Museum of American History, public domain; click to enlarge).

The relatively untroubled lives of the Robisons and their neighbors were about to change, however, in ways they could never have imagined, as their nation began its slide into one of its darkest periods in history with the secession of South Carolina from the United States on 20 December 1860.

The American Civil War

Mississippi, Florida and Alabama (9-11 January 1861). Georgia (19 January). Louisiana (26 January). Texas (1 February). The fall of Fort Sumter to Confederate States Army troops (13 April 1861).

The United States of America had fallen into a state of disunion through a rapid-fire series of events that stunned its citizens and quickly propelled them into a war of brother and cousin against brothers and cousins. Pennsylvanians by the hundreds, and then thousands, swiftly stood and marched for Washington, D.C. in answer to a call by President Abraham Lincoln for seventy-five thousand volunteers to defend the nation’s capital from a likely invasion by Confederate States troops.

Watching the hurried preparations of his parents’ friends and neighbors as they roused and readied themselves for war, the flames of H. B. Robinson’s adventurous spirit were also kindled. According to a later News-Herald account of his life, he “ran away from Tuscarora at the age of 13 and tried to enlist in the Union army, but was turned down on account of his age.” When the army commanded by Confederate General Robert E. Lee stormed across the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania, igniting the tide-turning Battle of Gettysburg during the fateful summer of 1863, he tried to enlist again, but was sternly rejected by Union Army recruiters again and sent back home.

Just fifteen years old when he was finally able to successfully enlist for military service with the Union Army, H. B. Robinson was enrolled in Mifflintown, Juniata County on 20 November 1863 by First Lieutenant William Wallace Geety of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Grievously wounded during the Battle of Pocotaligo South Carolina on 22 October 1862, Geety had been reassigned by his superiors to recruitment duties for the regiment to allow him more time to recover from his injuries. Eight days later (on 28 November 1863), H. B. Robinson officially mustered in for duty at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County as a private with Company C of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

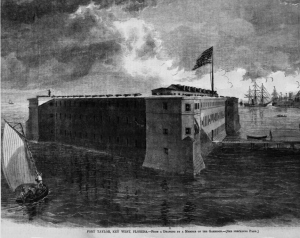

Subsequently referred to as “Brad” or “Brady” by at least one member of his regiment, according to descendants, he had connected with his regiment on 15 December via a recruiting depot and learned that he would be stationed with the other members of his company at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida.

Previously a large regiment with more than a thousand men swelling its ranks when it first arrived in America’s Deep South, the appearance of the 47th Pennsylvania had been radically reshaped in 1863 by the ravages of disease, which had thinned its ranks, and by orders from senior Union Army leaders that it be divided in two, with roughly half of the regiment assigned to garrison Fort Taylor and the other half sent to Fort Jefferson, which was located in the Gulf of Mexico, approximately seventy miles off the coast of Florida, and accessible only by ship.

Unidentified Union Army artillerymen standing next to one of the fifteen-inch Rodman guns installed on the third level of Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas, Florida, beginning in 1862. This smoothbore Rodman weighed twenty-five tons, and was able to fire four hundred and fifty-pound shells more than three miles (U.S. National Park Service, public domain).

The job of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers throughout 1863 had been to prevent the possible capture of both forts by the Confederate States Army or Navy, thereby ensuring that no foreign country would gain power over the United States by rendering aid to leaders of the Confederacy. According to Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan, “Seizure of these forts by coup de main” might very well have been the “first act of hostilities instituted by foreign powers” as Great Britain and other European countries altered their goal of abetting the secession of America’s southern states to taking control of territories that they now considered to be independent from the United States.

In response to that assignment, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were drilled regularly in artillery and infantry tactics at their respective duty stations. They also engaged in building rapport with the citizens of Union-occupied villages, towns and cities, as they strengthened the fortifications and other infrastructure aspects in those locations.

1864

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was altered further in response to orders that it expand the Union’s reach north by sending part of the regiment toward Fort Myers to retake possession of a federal installation that had been abandoned in 1858 after the federal government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. In response, Captain Richard Graeffe and a group of his soldiers from Company A, refurbished it and turned it into a shelter for pro-union supporters, escaped slaves, Confederate deserters, and others fleeing Rebel troops. They also began conducting cattle raids to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across Florida.

Red River Campaign

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had begun preparing for the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding the steamer Charles Thomas, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by the men from Companies E, F, G, and H.

Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost-fully-reunited regiment moved by train to Brashear City (now Morgan City, Louisiana) before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps (XIX Corps), and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks. (Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the soldiers from Company A were assigned to detached duty while awaiting transport that enabled them to reconnect with their regiment at Alexandria, Louisiana on 9 April).

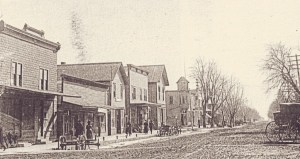

Natchitoches, Louisiana (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 7 May 1864, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

The early days on the ground quickly woke the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers up to just how grueling their new phase of duty would be. From 14-26 March, most members of the 47th marched for Alexandria and Natchitoches, near the top of the L-shaped state. Among the towns that the 47th Pennsylvanians passed through during their long marches were New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington.

From 4-5 April 1864, the regiment added to its roster of young Black soldiers when Aaron Bullard (later known as Aaron French), James Bullard, John Bullard, Samuel Jones, and Hamilton Blanchard (also known as John Hamilton) enrolled for military service with the 47th Pennsylvania at Natchitoches. According to their respective entries in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives and on regimental muster rolls, the men were officially mustered in for duty on 22 June at Morganza, Louisiana. Several of their entries noted that they were assigned the rank of “Colored Cook” while others were given the rank of “Under Cook.”

Often short on food and water throughout their long, harsh-climate trek, as part of the U.S. Army of the Gulf, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill (now the Village of Pleasant Hill) the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day.

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the second division, sixty members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were cut down on 8 April 1864 during the intense volley of fire unleashed in the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (also known as the Battle of Mansfield due to its proximity to the town of Mansfield). The fighting waned only when darkness fell. The exhausted, but uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded and dead. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate Major-General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner who was the son of Zachary Taylor, former president of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the Union force, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

During that engagement (now known as the Battle of Pleasant Hill), the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers succeeded in recapturing a Massachusetts artillery battery that had been lost during the earlier Confederate assault. Unfortunately, the regiment’s second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, and its two color-bearers, Sergeants Benjamin Walls and William Pyers, were wounded. Alexander sustained wounds to both of his legs, and Walls was shot in the left shoulder as he attempted to mount the 47th Pennsylvania’s colors on caissons that had been recaptured, while Pyers was wounded as he grabbed the flag from Walls to prevent it from falling into Confederate hands.

All three survived the day, however, and continued to serve with the regiment, but many others, like K Company’s Second Lieutenant Alfred Swoyer, were killed in action during those two days of chaotic fighting, or were wounded so severely that they were unable to continue the fight. (Swoyer’s final words were, “They’re coming nine deep!” Shot in the right temple shortly afterward, his body was never recovered.)

Still others were captured by Confederate troops, marched roughly one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford, a Confederate Army prison camp near Tyler, Texas, and held there as prisoners of war until they were released during prisoner exchanges that began on 22 July and continued through November. At least two members of the regiment never made it out of that prison camp alive; another died at a Confederate hospital in Shreveport.

Meanwhile, as the captured 47th Pennsylvanians were being spirited away to Camp Ford, the bulk of the regiment was carrying out orders from senior Union Army leaders to head for Grand Ecore, Louisiana. Encamped there from 11-22 April, they engaged in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications.

They then moved back to Natchitoches Parish on 22 April. While en route, they were attacked again, this time, at the rear of their retreating brigade, but they were able to end the encounter quickly and move on to reach Cloutierville at 10 p.m. that same night (after a forty-five-mile march).

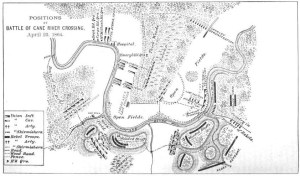

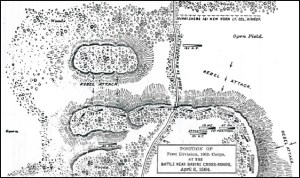

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were stationed just to the left of the “Thick Woods” with Emory’s 2nd Brigade, 1st Division as shown on this map of Union troop positions for the Battle of Cane River Crossing at Monett’s Ferry, Louisiana, 23 April 1864 (Major-General Nathaniel Banks’ official Red River Campaign Report, public domain).

The next morning (23 April), episodic skirmishing quickly roared into the flames of a robust fight. As part of the advance party led by Union Brigadier-General William Emory, the 47th Pennsylvanians took on the Confederate cavalry of Brigadier-General Hamilton P. Bee in the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry” or the “Cane River Crossing”).

Responding to a barrage from the Confederate artillery’s twenty-pound Parrott guns and raking fire from enemy troops positioned near a bayou and atop a bluff, Brigadier-General Emory directed one of his brigades to keep Bee’s Confederates busy while sending two other brigades to find a safe spot for the Union force to cross the Cane River. As part of the “beekeepers,” the 47th Pennsylvania supported Emory’s artillery.

Meanwhile, additional troops under Smith’s command, attacked Bee’s flank to force a Rebel retreat, and then erected a series of pontoon bridges that enabled the 47th Pennsylvania and other Union troops to make the Cane River Crossing by the next day. As the Confederates retreated, they torched their own food stores, as well as the cotton supplies of their fellow southerners. In a letter penned from Morganza, C Company Musician Henry Wharton described what had happened:

Our sojourn at Grand Ecore was for eleven days, during which time our position was well fortified by entrenchments for a length of five miles, made of heavy logs, five feet high and six feet wide, filled in with dirt. In front of this, trees were felled for a distance of two hundred yards, so that if the enemy attacked we had an open space before us which would enable our forces to repel them and follow if necessary. But our labor seemed to the men as useless, for on the morning of 22d April, the army abandoned these works and started for Alexandria. From our scouts it was ascertained that the enemy had passed some miles to our left with the intention of making a stand against our right at Bayou Cane, where there is a high bluff and dense woods, and at the same attack Smith’s forces who were bringing up the rear. This first day was a hard one on the boys, for at 10 o’clock at night they made Cloutierville, a distance of forty-five miles. On that day the rear was attacked which caused our forces to reverse their front and form in line of battle, expecting too, to go back to the relief of Smith, but he needed no assistance, sending word to the front that he had ‘whipped them, and could do it again.’ It was well that Banks made so long a march on that day, for on the next we found the enemy prepared to carry out their design of attacking us front and rear. Skirmishing commenced early in the morning and as our columns advanced he fell back towards the bayou, when we soon discovered the position of their batteries on the bluff. There was then an artillery duel by the smaller pieces, and some sharp fighting by the cavalry, when the ‘mule battery,’ twenty pound Parrott guns opened a heavy fire, which soon dislodged them, forcing the chivalry to flee in a manner not at all suitable to their boasted courage. Before this one cavalry, the 3d Brigade of the 1st Div., and Birges’ brigade of the second, had crossed the bayou and were doing good service, which, with the other work, made the enemy show their heels. The 3d brigade done some daring deeds in this fight, as also did the cavalry. In one instance the 3d charged up a hill almost perpendicular, driving the enemy back by the bayonet without firing a gun. The woods on this bluff was so thick that the cavalry had to dismount and fight on foot. During the whole of the day, our brigade, the 2d, was supporting artillery, under fire all the time, and could not give Mr. Reb a return shot.

While we were fighting in front, Smith was engaged some miles in the rear, but he done his part well and drove them back. The rebel commanders thought by attacking us in the rear, and having a large face on the bluffs, they would be able to capture our train and take us all prisoners, but in this they were mistaken, for our march was so rapid that we were on them before they had thrown up the necessary earthworks. Besides they underrated the amount of our artillery, calculating from the number engaged at Pleasant Hill. The rebels say ‘it seems as though the Yankees manufacture, on short notice, artillery to order, and the men are furnished with wings when they wish to make a certain point.’

The damage done to the Confederate cause by the burning of cotton was immense. On the night of the 22d our route was lighted up for miles and millions of dollars worth of this production was destroyed. This loss will be felt more by Davis & Co., than several defeats in this region, for the basis of the loan in England was on the cotton in Louisiana.

After the rebels had fled from the bluff the negro troops put down the pontoons, and by ten that night we were six miles beyond the bayou safely encamped. The next morning we moved forward and in two days were in Alexandria. Johnnys followed Smith’s forces, keeping out of range of his guns, except when he had gained the eminence across the bayou, when he punished them (the rebs) severely.

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” in reference to the Union officer who oversaw its construction, Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 facilitated Union gunboat passage (public domain).

Having finally reached Alexandria on 26 April, they learned they would remain at their latest new camp for at least two weeks. Placed temporarily under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, they were assigned yet again to the hard labor of construction work, helping to erect “Bailey’s Dam,” a timber structure that was designed to enable Union Navy gunboats to safely navigate the fluctuating waters of the Red River. According to Wharton:

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gun boats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people will eat), so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the iron clads down the river. After a great deal of labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic, chute], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’ The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gun boat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

Continuing their march, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers headed toward Avoyelles Parish. According to Wharton:

On Sunday, May 15th, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of the Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad where with the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. – We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed in line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired, and we advanced ’till dark, when the forces halted for the night with orders to rest on their arms. – ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee.

“Sleeping on Their Arms” by Winslow Homer (Harper’s Weekly, 21 May 1864).

“Resting on their arms,” (half-dozing, without pitching their tents, and with their rifles right beside them), they were now positioned just outside of Marksville, on the eve of the 16 May 1864 Battle of Mansura, which unfolded as follows, according to Wharton:

Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, they reached Missoula [sic, Mansura], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic, maneuvering] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic, were] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain correctly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport [sic, Simmesport] on the Achafalaya [sic, Atchafalaya] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over. – The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of the army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic, there] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.

Union Army base at Morganza Bend, Louisiana, circa 1863-1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Continuing on, Private H. B. Robinson and the other surviving members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry marched for Simmesport and then Morganza, where they made camp again. While encamped there, the nine formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the regiment in Beaufort, South Carolina (October 1862) and Natchitoches, Louisiana (April 1864) were officially mustered into the regiment between 20-24 June 1864.

The regiment then moved on and arrived in New Orleans in late June. On the Fourth of July, members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry received news that dampened the spirit of Independence Day for many. Their war was not yet over; they were heading back to the Eastern Theater of battle.

Three days later, on 7 July, Private H. B. Robinson and his fellow C Company comrades boarded the U.S. Steamer McClellan and sailed out of the harbor at New Orleans with the members of Companies A, D, E, F, H, and I. (The men from Companies B, G and K would depart later that month and reconnect with the regiment at Monocacy.)

An Encounter with Lincoln and Snicker’s Gap

Following their arrival in Virginia and a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln on 12 July, the advance group of 47th Pennsylvanians joined up with Major-General David Hunter’s forces in mid-July 1864, at Snicker’s Gap, Virginia, where they fought in the Battle of Cool Spring and subsequently assisted in defending Washington, D.C. while also helping to drive Confederate troops from Maryland.

On 24 July 1864, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin was promoted from leadership of Company C to the 47th Pennsylvania’s central regimental command staff and was also awarded the rank of major. First Lieutenant Daniel Oyster was soon tapped to fill Gobin’s shoes—a promotion that was made official when he was commissioned as captain of C Company on 1 September 1864.

That same day, William Hendricks was promoted from second to first lieutenant, Sergeant Christian S. Beard was promoted to second lieutenant, Sergeant William Fry was promoted to the rank of first sergeant, Private John Bartlow was promoted to the rank of sergeant, and Private Timothy M. Snyder was promoted to the rank of corporal.

By that point, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had become part of the Middle Military Division of the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah and were serving under Major-General Philip H. Sheridan.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

General Crook’s Battle Near Berryville, Virginia, September 3, 1864 (James E. Taylor, public domain).

From 3-4 September, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers fought in the Battle of Berryville, Virginia and engaged in related post-battle skirmishes with the enemy over subsequent days. On one of those days (5 September 1864), Captain Oyster and Private David Sloan, were wounded at Berryville. Both received medical treatment and returned to duty with the regiment.

Roughly two weeks later, Color-Bearer Benjamin Walls, the oldest member of the entire regiment, was mustered out upon expiration of his three-year term of service on 18 September—despite his request that he continued to be allowed to continue his service to the nation. C Company Privates D. W. and Isaac Kemble, David S. Beidler, R. W. Druckemiller, Charles Harp, John H. Heim, former prisoner of war Conrad Holman, George Miller, William Pfeil, William Plant, and Alex Ruffaner also mustered out the same day upon expiration of their respective terms of service.

Valor and Persistence

Inflicting heavy casualties during the Battle of Opequan (also known as “Third Winchester”) on 19 September 1864, Sheridan’s gallant blue jackets forced a stunning retreat of Jubal Early’s grays—first to Fisher’s Hill (21-22 September) and then, following a successful early morning flanking attack, to Waynesboro. These impressive Union victories helped Abraham Lincoln secure his second term as president. Recalling the battle years later, Sheridan noted:

My army moved at 3 o’clock that morning. The plan was for Torbert to advance with Merritt’s division of cavalry from Summit Point, carry the crossings of the Opequon at Stevens’s and Lock’s fords, and form a junction near Stephenson’s depot, with Averell, who was to move south from Darksville by the Valley pike. Meanwhile, Wilson was to strike up the Berryville pike, carry the Berryville crossing of the Opequon, charge through the gorge or cañon on the road west of the stream, and occupy the open ground at the head of this defile. Wilson’s attack was to be supported by the Sixth and Nineteenth corps, which were ordered to the Berryville crossing, and as the cavalry gained the open ground beyond the open gorge, the two infantry corps, under command of General Wright, were expected to press on after and occupy Wilson’s ground, who was then to shift to the south bank of Abraham’s creek and cover my left; Crook’s two divisions, having to march from Summit Point, were to follow the Sixth and Nineteenth corps to the Opequon, and should they arrive before the action began, they were to be held in reserve till the proper moment came, and then, as a turning-column, be thrown over toward the Valley pike, south of Winchester.

By dawn on 19 September, the brigade from Wilson’s division, headed by McIntosh, had succeeded in compelling Confederate pickets to flee their Berryville positions with “Wilson following rapidly through the gorge with the rest of the division, debouched from its western extremity with such suddenness as to capture a small earthwork in front of General Ramseur’s main line.” Although “the Confederate infantry, on recovering from its astonishment, tried hard to dislodge them,” they were unable to do so, according to Sheridan. Wilson’s Union troops were then reinforced by the U.S. 6th Army.

I followed Wilson to select the ground on which to form the infantry. The Sixth Corps began to arrive about 8 o’clock, and taking up the line Wilson had been holding, just beyond the head of the narrow ravine, the cavalry was transferred to the south side of Abraham’s Creek.

The Confederate line lay along some elevated ground about two miles east of Winchester, and extended from Abraham’s Creek north across the Berryville pike, the left being hidden in the heavy timber on Red Bud Run. Between this line and mine, especially on my right, clumps of woods and patches of underbrush occurred here and there, but the undulating ground consisted mainly of open fields, many of which were covered with standing corn that had already ripened.

“The 6th Corps formed across the Berryville Road” while the “19th Corps prolonged the line to the Red Bud on the right with the troops of the Second Division.” According to military historian Richard Irwin, the:

First Division’s First and Second Brigades, under Beal and McMillan, formed in the rear of the Second Division and on the right flank. Beal’s First Brigade was on the right of the division’s position, and McMillan’s Second Brigade deployed on the left and rear of Beal; in order of the 47th Pennsylvania, 8th Vermont, 160th New York, and 12th Connecticut, with five companies of the 47th Pennsylvania deployed to cover the whole right flank of his brigade and to move forward with it by the flank left in front. By this time, the Army of West Virginia had crossed the ford and was massed on the left of the west bank.

While the ground in front of the 6th Corps was for the most part open, the 19th Corps found itself in a dense wood, restricting its vision of both the enemy and its own forces.

“Much time was lost in getting all of the Sixth and Nineteenth corps through the narrow defile,” Sheridan observed, adding that, because Grover’s division was “greatly delayed there by a train of ammunition wagons … it was not until late in the forenoon that the troops intended for the attack could be got into line ready to advance.” As a result:

General Early was not slow to avail himself of the advantages thus offered him, and my chances of striking him in detail were growing less every moment, for Gordon and Rodes were hurrying their divisions from Stephenson’s depot across-country on a line that would place Gordon in the woods south of Red Bud Run, and bring Rodes into the interval between Gordon and Ramseur.

When the two corps had all got through the cañon they were formed with Getty’s division of the Sixth to the left of the Berryville pike, Rickett’s division to the right of the pike, and Russell’s division in reserve in rear of the other two. Grover’s division of the Nineteenth Corps came next on the right of Rickett’s, with Dwight to its rear in reserve, while Crook was to begin massing near the Opequon crossing about the time Wright and Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers] were ready to attack.

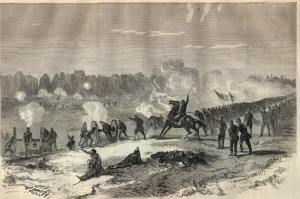

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union Army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces, Battle of Opequan, 19 September 1864 (Kurz & Allison, circa 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

More than a quarter of a century after the clash, Irwin conjured the spirit of the battle’s beginning:

About a quarter before twelve o’clock, at the sound of Sheridan’s bugle, repeated from corps, division, and brigade headquarters, the whole line moved forward with great spirit, and instantly became engaged. Wilson pushed back Lomax, Wright drove in Ramseur, while Emory, advancing his infantry [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers] rapidly through the wood, where he was unable to use his artillery, attacked Gordon with great vigor. Birge, charging with bayonets fixed, fell upon the brigade of Evans, forming the extreme left of Gordon, and without a halt drove it in confusion through the wood and across the open ground beyond to the support of Braxton’s artillery, posted by Gordon to secure his flank on the Red Bud road. In this brilliant charge, led by Birge in person, his lines naturally became disordered….

Sharpe, advancing simultaneously on Birge’s left, tried in vain to keep the alignment with Ricketts and with Birge…. At first the order of battle formed a right angle with the road, but the bend once reached, in the effort to keep closed upon it, at every step Ricketts was taking ground more and more to the left, while the point of direction for Birge, and equally for Sharpe, was the enemy in their front, standing almost in the exact prolongation of the defile, from which line, still plainly marked by Ash Hollow, the road … was steadily diverging.

As the battle continued to unfold, the disorganization affected the lines on both sides of the conflict. According to Irwin:

The 19th Corps Second Division was initially successful, but in its charge became disorganized; and the troops on the left in following the less obstructed area of the road which veared [sic] slightly left, soon opened up a gap on their right; while the remainder of the Union forces were moving straight ahead as they engaged the Confederates. This gap eventually reached 400 yards in width, an opportunity the Confederates soon exploited. Fortunately the Confederates were soon themselves disorganized by their advance, and encountering fresh Union troops on their right flank were halted. The Confederate attack on the right flank also achieved initial success, until halted by Beal’s first brigade.

McMillan had been ordered to move forward at the same time as Beal, and to form on his left. The five companies of the 47th Pennsylvania that had been detached to form a skirmish line on the Red Bud Run to cover McMillan’s right flank, had some how [sic] lost their way on the broken ground among the thickets, and, not finding them in place, McMillan had been obliged to send the remaining companies of the same regiment to do the same duty, and brought the rest of the brigade to the front to restore the line. The line then charged and drove the Confederates back beyond the positions where their attack had started. The initial engagement had lasted barely an hour, and by 1 PM was over. The right flank of the 19th Corps was held by the 47th Pennsylvania and 30th Massachusetts.

First State Color, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (presented to the regiment by Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin, 20 September 1861; retired 11 May 1865, public domain).

According to Sheridan:

Just before noon the line of Getty, Ricketts, and Grover moved forward, and as we advanced, the Confederates, covered by some heavy woods on their right, slight underbrush and corn-fields along their centre [sic], and a large body of timber on their left along the Red Bud, opened fire from their whole front. We gained considerable ground at first, especially on our left but the desperate resistance which the right met with demonstrated that the time we had unavoidably lost in the morning had been of incalculable value to Early, for it was evident that he had been enabled already to so far concentrate his troops as to have the different divisions of his army in a connected line of battle in good shape to resist.

Getty and Ricketts made some progress toward Winchester in connection with Wilson’s cavalry…. Grover in a few minutes broke up Evans’s brigade of Gordon’s division, but his pursuit of Evans destroyed the continuity of my general line, and increased an interval that had already been made by the deflection of Ricketts to the left, in obedience to instructions that had been given him to guide his division on the Berryville pike. As the line pressed forward, Ricketts observed this widening interval and endeavored to fill it with the small brigade of Colonel Keifer, but at this juncture both Gordon and Rodes struck the weak spot where the right of the Sixth Corps and the left of the Nineteenth should have been in conjunction, and succeeded in checking my advance by driving back a part of Ricketts’s division, and the most of Grover’s. As these troops were retiring I ordered Russell’s reserve division to be put into action, and just as the flank of the enemy’s troops in pursuit of Grover was presented, Upton’s brigade, led in person by both Russell and Upton, struck it in a charge so vigorous as to drive the Confederates back … to their original ground.

The success of Russell enabled me to re-establish the right of my line some little distance in advance of the position from which it started in the early morning, and behind Russell’s division (now commanded by Upton) the broken regiments of Ricketts’s division were rallied. Dwight’s division was then brought up on the right, and Grover’s men formed behind it….

No news of Torbert’s progress came … so … I directed Crook to take post on the right of the Nineteenth Corps and, when the action was renewed, to push his command forward as a turning-column in conjunction with Emory. After some delay … Crook got his men up, and posting Colonel Thoburn’s division on the prolongation of the Nineteenth Corps, he formed Colonel Duval’s division to the right of Thoburn. Here I joined Crook, informing him that … Torbert was driving the enemy in confusion along the Martinsburg pike toward Winchester; at the same time I directed him to attack the moment all of Duval’s men were in line. Wright was introduced to advance in concert with Crook, by swinging Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania and his other 19th Corps’ troops] and the right of the Sixth Corps to the left together in a half-wheel. Then leaving Crook, I rode along the Sixth and Nineteenth corps, the open ground over which they were passing affording a rare opportunity to witness the precision with which the attack was taken up from right to left. Crook’s success began the moment he started to turn the enemy’s left…

Both Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] and Wright took up the fight as ordered…. [A]s I reached the Nineteenth Corps the enemy was contesting the ground in its front with great obstinacy; but Emory’s dogged persistence was at length rewarded with success, just as Crook’s command emerged from the morass of the Red Bud Run, and swept around Gordon, toward the right of Breckenridge….”

As “Early tried hard to stem the tide” of the multi-pronged Union assault, “Torbert’s cavalry began passing around his left flank, and as Crook, Emory, and Wright attacked in front, panic took possession of the enemy, his troops, now fugitives and stragglers, seeking escape into and through Winchester,” according to Sheridan.

When this second break occurred, the Sixth and Nineteenth corps were moved over toward the Millwood pike to help Wilson on the left, but the day was so far spent that they could render him no assistance.” The battle winding down, Sheridan headed for Winchester to begin writing his report to Grant.

According to Irwin, although the heat of battle had cooled by 1 p.m., troop movements had continued on both sides throughout the afternoon until “Crook, with a sudden … effective half-wheel to the left, fell vigorously upon Gordon, and Torbert coming on with great impetuosity … the weight was heavier than the attenuated lines of Breckinridge and Gordon Could bear.” As a result, “Early saw his whole left wing give back in disorder, and as Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] and Wright pressed hard, Rodes and Ramseur gave way, and the battle was over.”

Early vainly endeavored to reconstruct his shattered lines [near Winchester]. About five o’clock Torbert and Crook, fairly at right angles to the first line of battle, covered Winchester on the north from the rocky ledges that lie to the eastward of the town…. Thence Wright extended the line at right angles with Crook and parallel with the valley road, while Sheridan drew out Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] … and sent him to extend Wright’s line to the south….

Sheridan, mindful that his men had been on their feet since two o’clock in the morning … made no attempt to send his infantry after the flying enemy….

Sheridan, mindful that his men had been on their feet since two o’clock in the morning … made no attempt to send his infantry after the flying enemy….

Summing up the battle for Lincoln and Grant, Sheridan reported:

My losses in the Battle of Opequon were heavy, amounting to about 4,500 killed, wounded and missing. Among the killed was General Russell, commanding a division, and the wounded included Generals Upton, McIntosh and Chapman, and Colonels Duval and Sharpe. The Confederate loss in killed, wounded, and prisoners equaled about mine. General Rodes being of the killed, while Generals Fitzhugh Lee and York were severely wounded.

We captured five pieces of artillery and nine battle flags. The restoration of the lower valley – from the Potomac to Strasburg – to the control of the Union forces caused great rejoicing in the North, and relieved the Administration from further solicitude for the safety of the Maryland and Pennsylvania borders. The President’s appreciation of the victory was expressed in a despatch [sic] so like Mr. Lincoln I give a fac-simile [sic] of it to the reader. This he supplemented by promoting me to the grade of brigadier-general in the regular army, and assigning me to the permanent command of the Middle Military Department, and following that came warm congratulations from Mr. Stanton and from Generals Grant, Sherman and Meade.

“The losses of the Army of the Shenandoah, according to the revised statements compiled in the War Department, were 5018, including 697 killed, 3983 wounded, 338 missing,” per revised estimates by Irwin. “Of the three infantry corps, the 19th, though in numbers smaller than the 6th, suffered the heaviest loss, the aggregate being 2074 [314 killed, 1554 wounded, 206 missing]. Conversely, Early “lost nearly 4000 in all, including about 200 prisoners; or as other sources reported, anywhere from 5500 to 6850 killed, wounded, and missing or captured.”

Despite the significant number of killed, wounded and missing on both sides of the conflict, casualties within the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were surprisingly low. Private Thomas Steffen of Company B was killed in action while F Company Private William H. Jackson’s cause of death was somewhat less clear; he was reported in Samuel Bates’ History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5 as having died on the same day on which the battle took place.

Among the injured were C Company Corporal Timothy Matthias Snyder, who was wounded in the knee, and Privates William Adams (E Company), Charles Pfeiffer (B Company), who lost the forefinger of his right hand, J. D. Rabenold (B Company), and Edward Smith (E Company).

As he penned his memoir in 1885 during the final days of his life, President Ulysses S. Grant again made clear the significance of the Battle of Opequan:

Sheridan moved at the time he had fixed upon. He met Early at the crossing of Opequon Creek [September 19], and won a most decisive victory – one which electrified the country. Early had invited this attack himself by his bad generalship and made the victory easy. He had sent G. T. Anderson’s division east of the Blue Ridge [to Lee] before I [Grant] went to Harpers Ferry and about the time I arrived there he started with two other divisions (leaving but two in their camps) to march to Martinsburg for the purpose of destroying the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad at that point. Early here learned that I had been with Sheridan and, supposing there was some movement on foot, started back as soon as he got the information. But his forces were separated and … he was very badly defeated. He fell back to Fisher’s Hill, Sheridan following.

On 23-24 September, the 47th Pennsylvania’s two most senior officers, Colonel Tilghman Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, mustered out upon expiration of their respective terms of service.

The Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, “Surprise at Cedar Creek,” captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle-pit positions, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

On 19 October 1864, Early’s Confederate forces briefly stunned the Union Army, launching a surprise attack at Cedar Creek, but Sheridan was able to rally his troops. Intense fighting raged for hours and ranged over a broad swath of Virginia farmland. Weakened by hunger wrought by the Union’s earlier destruction of crops, Early’s army gradually peeled off, one by one, to forage for food while Sheridan’s forces fought on, and won the day during the epic Battle of Cedar Creek.

According to Union General Ulysses S. Grant:

On the 18th of October Early was ready to move, and during the night succeeded in getting his troops in the rear of our left flank, which fled precipitately and in great confusion down the valley, losing eighteen pieces of artillery and a thousand or more prisoners [Battle of Cedar Creek]. The right under General Getty maintained a firm and steady front, falling back to Middletown where it took a position and made a stand. The cavalry went to the rear, seized the roads leading to Winchester and held them for the use of our troops in falling back, General Wright having ordered a retreat back to that place.

Sheridan having left Washington on the 18th, reached Winchester that night. The following morning he started to join his command. He had scarcely got out of town, when he met his men returning, in panic from the front and also heard heavy firing to the south. He immediately ordered the cavalry at Winchester to be deployed across the valley to stop the stragglers. Leaving members of his staff to take care of Winchester and the public property there, he set out with a small escort directly for the scene of the battle. As he met the fugitives he ordered them to turn back, reminding them that they were going the wrong way. His presence soon restored confidence. Finding themselves worse frightened than hurt the men did halt and turn back. Many of those who had run ten miles got back in time to redeem their reputation as gallant soldiers before night.

Not provided with adequate intelligence by his staff by that fateful morning, Sheridan had begun his day at a leisurely pace, clearly unaware of the potential disaster in the making:

Toward 6 o’clock the morning of the 19th, the officer on picket duty at Winchester came to my room, I being yet in bed, and reported artillery firing from the direction of Cedar Creek. I asked him if the firing was continuous or only desultory, to which he replied that it was not a sustained fire, but rather irregular and fitful. I remarked: ‘It’s all right; Grover has gone out this morning to make a reconnaissance, and he is merely feeling the enemy.’ I tried to go to sleep again, but grew so restless that I could not, and soon got up and dressed myself. A little later the picket officer came back and reported that the firing, which could be distinctly heard from his line on the heights outside of Winchester, was still going on. I asked him if it sounded like a battle, and as he again said that it did not, I still inferred that the cannonading was caused by Grover’s division banging away at the enemy simply to find out what he was up to. However, I went down-stairs and requested that breakfast be hurried up, and at the same time ordered the horses to be saddled and in readiness, for I concluded to go to the front before any further examinations were made in regard to the defensive line.

We mounted our horses between half-past 8 and 9, and as we were proceeding up the street which leads directly through Winchester, from the Logan residence, where Edwards was quartered, to the Valley pike, I noticed that there were many women at the windows and doors of the houses, who kept shaking their skirts at us and who were otherwise markedly insolent in their demeanor, but supposing this conduct to be instigated by their well-known and perhaps natural prejudices, I ascribed to it no unusual significance. On reaching the edge of town I halted a moment, and there heard quite distinctly the sound of artillery firing in an unceasing roar. Concluding from this that a battle was in progress, I now felt confident that the women along the street had received intelligence from the battlefield by the ‘grape-vine telegraph,’ and were in raptures over some good news, while I as yet was utterly ignorant of the actual situation. Moving on, I put my head down toward the pommel of my saddle and listened intently, trying to locate and interpret the sound, continuing in this position till we had crossed Mill Creek, about half a mile from Winchester. The result of my efforts in the interval was the conviction that the travel of the sound was increasing too rapidly to be accounted for by my own rate of motion, and that therefore my army must be falling back.

At Mill Creek my escort fell in behind, and we were going ahead at a regular pace, when, just as we made the crest of the rise beyond the stream, there burst upon our view the appalling spectacle of a panic-stricken army – hundreds of slightly wounded men, throngs of others unhurt but utterly demoralized, and baggage-wagons by the score, all pressing to the rear in hopeless confusion, telling only too plainly that a disaster had occurred at the front. On accosting some of the fugitives, they assured me that the army was broken up, in full retreat, and that all was lost; all this with a manner true to that peculiar indifference that takes possession of panic-stricken men. I was greatly disturbed by the sight, but at once sent word to Colonel Edwards, commanding the brigade in Winchester, to stretch his troops across the valley, near Mill Creek, and stop all fugitives, directing also that the transportation be passed through and parked on the north side of the town.

As I continued at a walk a few hundred yards farther, thinking all the time of Longstreet’s telegram to Early, ‘Be ready when I join you, and we will crush Sheridan,’ I was fixing in my mind what I should do. My first thought was to stop the army in the suburbs of Winchester as it came back, form a new line, and fight there; but as the situation was more maturely considered a better conception prevailed. I was sure the troops had confidence in me, for heretofore we had been successful; and as at other times they had seen me present at the slightest sign of trouble or distress, I felt that I ought to try now to restore their broken ranks, or, failing in that, to share their fate because of what they had done hitherto.

About this time Colonel Wood, my chief commissary, arrived from the front and gave me fuller intelligence, reporting that everything was gone, my headquarters captured, and the troops dispersed. When I heard this I took two of my aides-de-camp, Major George A. Forsyth and Captain Joseph O’Keefe, and with twenty men from the escort started for the front, at the same time directing Colonel James W. Forsyth and Colonels Alexander and Thom to remain behind and do what they could to stop the runaways.

For a short distance I traveled on the road, but soon found it so blocked with wagons and wounded men that my progress was impeded, and I was forced to take to the adjoining fields to make haste. When most of the wagons and wounded were past I returned to the road, which was thickly lined with unhurt men, who, having got far enough to the rear to be out of danger, had halted without any organization, and begun cooking coffee, but when they saw me they abandoned their coffee, threw up their hats, shouldered their muskets, and as I passed along turned to follow with enthusiasm and cheers. To acknowledge this exhibition of feeling I took off my hat, and with Forsyth and O’Keefe rode some distance in advance of my escort, while every mounted officer who saw me galloped out on either side of the pike to tell the men at a distance that I had come back. In this way the news was spread to the stragglers off the road, when they, too, turned their faces to the front and marched toward the enemy, changing in a moment from the depths of depression to the extreme of enthusiasm. I already knew that even in the ordinary condition of mind enthusiasm is a potent element with soldiers, but what I saw that day convinced me that if it can be excited from a state of despondency its power is almost irresistible. I said nothing except to remark, as I rode among those on the road: ‘If I had been with you this morning this disaster would not have happened. We must face the other way; we will go back and recover our camp.’

My first halt was made just north of Newtown, where I met a chaplain digging his heels into the sides of his jaded horse, and making for the rear with all possible speed. I drew up for an instant, and inquired of him how matters were going at the front. He replied, ‘Everything is lost; but all will be right when you get there’; yet notwithstanding this expression of confidence in me, the parson at once resumed his breathless pace to the rear. At Newtown I was obliged to make a circuit to the left, to get round the village. I could not pass through it, the streets were so crowded, but meeting on this detour Major McKinley, of Crook’s staff, he spread the news of my return through the motley throng there.

According to Grant, “When Sheridan got to the front he found Getty and Custer still holding their ground firmly between the Confederates and our retreating troops.”

Everything in the rear was now ordered up. Sheridan at once proceeded to intrench [sic] his position; and he awaited an assault from the enemy. This was made with vigor, and was directed principally against Emory’s corps [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers], which had sustained the principal loss in the first attack. By one o’clock the attack was repulsed. Early was so badly damaged that he seemed disinclined to make another attack, but went to work to intrench [sic] himself with a view to holding the position he had already gained….

Sheridan Rallying His Troops, Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

What Sheridan encountered as he approached Newtown and the Valley pike from the south made him urge Rienzi on:

I saw about three-fourths of a mile west of the pike a body of troops, which proved to be Rickett’s and Wheaton’s divisions of the Sixth Corps, and then learned that the Nineteenth Corps [to which the 47th Pennsylvania had been assigned] had halted a little to the right and rear of these; but I did not stop, desiring to get to the extreme front. Continuing on parallel with the pike, about midway between Newtown and Middletown I crossed to the west of it, and a little later came up in rear of Getty’s division of the Sixth Corps. When I arrived, this division and the cavalry were the only troops in the presence of and resisting the enemy; they were apparently acting as a rear guard at a point about three miles north of the line we held at Cedar Creek when the battle began. General Torbert was the first officer to meet me, saying as he rode up, ‘My God! I am glad you’ve come.’ Getty’s division, when I found it, was about a mile north of Middleton, posted on the reverse slope of some slightly rising ground, holding a barricade made with fence-rails, and skirmishing slightly with the enemy’s pickets. Jumping my horse over the line of rails, I rode to the crest of the elevation, and there taking off my hat, the men rose up from behind their barricade with cheers of recognition. An officer of the Vermont brigade, Colonel A. S. Tracy, rode out to the front, and joining me, informed me that General Louis A. Grant was in command there, the regular division commander General Getty, having taken charge of the Sixth Corps in place of Ricketts, wounded early in the action, while temporarily commanding the corps. I then turned back to the rear of Getty’s division, and as I came behind it, a line of regimental flags rose up out of the ground, as it seemed, to welcome me. They were mostly the colors of Crook’s troops, who had been stampeded and scattered in the surprise of the morning. The color-bearers, having withstood the panic, had formed behind the troops of Getty. The line with the colors was largely composed of officers, among whom I recognized Colonel R. B. Hayes, since president of the United States, one of the brigade commanders. At the close of this incident I crossed the little narrow valley, or depression, in rear of Getty’s line, and dismounting on the opposite crest, established that point as my headquarters. In a few minutes some of my staff joined me, and the first directions I gave were to have the Nineteenth Corps [to which the 47th Pennsylvania was attached] and the two divisions of Wright’s corps brought to the front, so they could be formed on Getty’s division prolonged to the right; for I had already decided to attack the enemy from that line as soon as I could get matters in shape to take the offensive. Crook met me at this time, and strongly favored my idea of attacking, but said, however, that most of his troops were gone. General Wright came up a little later, when I saw that he was wounded, a ball having grazed the point of his chin so as to draw the blood plentifully.

Wright gave me a hurried account of the day’s events, and when told that we would fight the enemy on the line which Getty and the cavalry were holding, and that he must go himself and send all his staff to bring up the troops, he zealously fell in with the scheme; and it was then that the Nineteenth Corps [including the 47th Pennsylvania] and two divisions of the Sixth were ordered to the front from where they had been halted to the right and rear of Getty.

After this conversation I rode to the east of the Valley pike and to the left of Getty’s division, to a point from which I could obtain a good view of the front, in the mean time [sic] sending Major Forsyth to communicate with Colonel Lowell (who occupied a position close in toward the suburbs of Middletown and directly in front of Getty’s left) to learn whether he could hold on there. Lowell replied that he could. I then ordered Custer’s division back to the right flank, and returning to the place where my headquarters had been established I met near them Rickett’s division under General Kiefer and General Frank Wheaton’s division, both marching to the front. When the men of these divisions saw me they began cheering and took up the double quick to the front, while I turned back toward Getty’s line to point out where these returning troops should be place. Having done this, I ordered General Wright to resume command of the Sixth Corps, and Getty, who was temporarily in charge of it, to take command of his own division. A little later the Nineteenth Corps [including the 47th Pennsylvania] came up and was posted between the right of the Sixth Corps and Middle Marsh Brook.

All this had consumed a great deal of time, and I concluded to visit again the point to the east of the Valley pike, from where I had first observed the enemy, to see what he was doing. Arrived there, I could plainly seem him getting ready for attack, and Major Forsyth now suggested that it would be well to ride along the line of battle before the enemy assailed us, for although the troops had learned of my return, but few of them had seen me. Following his suggestion I started in behind the men, but when a few paces had been taken I crossed to the front and, hat in hand, passed along the entire length of the infantry line; and it is from this circumstance that many of the officers and men who then received me with such heartiness have since supposed that that was my first appearance on the field. But at least two hours had elapsed since I reached the ground, for it was after mid-day when this incident of riding down the front took place, and I arrived not later, certainly, than half-past 10 o’clock.

After re-arranging the line and preparing to attack I returned again to observe the Confederates, who shortly began to advance on us. The attacking columns did not cover my entire front, and it appeared that their onset would be mainly directed against the Nineteenth Corps [including the 47th Pennsylvania], so, fearing that they might be too strong for Emory on account of his depleted condition (many of his men not having had time to get up from the rear), and Getty’s division being free from assault, I transferred a part of it from the extreme left to the support of the Nineteenth Corps. The assault was quickly repulsed by Emory, however, and as the enemy fell back Getty’s troops were returned to their original place. This repulse of the Confederates made me feel pretty safe from further offensive operations on their part, and I now decided to suspend the fighting till my thin ranks were further strengthened by the men who were continually coming up from the rear, and particularly till Crook’s troops could be assembled on the extreme left.

In consequence of the despatch [sic] already mentioned, ‘Be ready when I join you, and we will crush Sheridan,’ since learned to have been fictitious, I had been supposing all day that Longstreet’s troops were present, but as no definite intelligence on this point had been gathered, I concluded, in the lull that now occurred, to ascertain something positive regarding Longstreet; and Merritt having been transferred to our left in the morning, I directed him to attack an exposed battery then at the edge of Middletown, and capture some prisoners. Merritt soon did this work effectually, concealing his intention till his troops got close in to the enemy, and then by a quick dash gobbling up a number of Confederates. When the prisoners were brought in, I learned from them that the only troops of Longstreet’s in the fight were of Kershaw’s division, which had rejoined Early at Brown’s Gap in the latter part of September, and that the rest of Longstreet’s corps was not on the field. The receipt of this information entirely cleared the way for me to take the offensive, but on the heels of it came information that Longstreet was marching by the Front Royal pike to strike my rear at Winchester, driving Powell’s cavalry in as he advanced. This renewed my uneasiness, and caused me to delay the general attack till after assurances came from Powell, denying utterly the reports as to Longstreet, and confirming the statements of the prisoners.

Launching another advance sometime mid-afternoon during which Sheridan “sent his cavalry by both flanks, and they penetrated to the enemy’s rear,” Grant added:

The contest was close for a time, but at length the left of the enemy broke, and disintegration along the whole line soon followed. Early tried to rally his men, but they were followed so closely that they had to give way very quickly every time they attempted to make a stand. Our cavalry, having pushed on and got in the rear of the Confederates, captured twenty-four pieces of artillery, besides retaking what had been lost in the morning. This victory pretty much closed the campaign in the Valley of Virginia. All the Confederate troops were sent back to Richmond with the exception of one division of infantry and a little cavalry. Wright’s corps was ordered back to the Army of the Potomac, and two other divisions were withdrawn from the valley. Early had lost more men in killed, wounded and captured in the valley than Sheridan had commanded from first to last.

The High Price of Valor

Headstone of Sergeant William Pyers, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Company C, Winchester National Cemetery, Virginia; he was killed in the fighting at the Cooley Farm during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (courtesy of Randy Fletcher, 2014).

But it was an extremely costly engagement for Pennsylvania’s native sons. The 47th experienced a total of one hundred and seventy-six casualties during the Battle of Cedar Creek alone, including Sergeants John Bartlow and William Pyers, and Privates James Brown (a carpenter), Jasper B. Gardner (a railroad conductor), George W. Keiser (an eighteen-year-old farmer), Joseph Smith, John E. Will, and Theodore Kiehl—all dead.

Most of those deceased heroes were simply described in the U.S. Army’s death ledger for 1864 as “killed in action.” Many were initially buried near where they fell and then later exhumed and reinterred at the Winchester National Cemetery in Winchester, Virginia, during the federal government’s large-scale effort to properly bury Union Army soldiers at national cemeteries.

In recounting the events of that terrible day in a letter later sent to the Sunbury American, Corporal Henry Wharton wrote, “This victory was, to us, of company C, dearly brought, and will bring with it sorrow to more than one Sunbury family.”

A Warrior-Poet Pays Tribute to the Courage of His Comrades

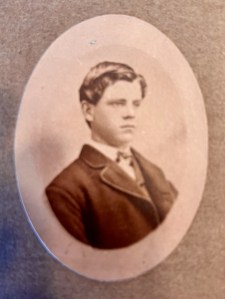

H. B. Robinson’s 1865 photo is presented through the generosity of Amy (Lowers) Maurer, and is being used with her permission. It may not be reproduced, repurposed, or shared without the permission of Amy Maurer.

Sometime after that epic engagement with the Confederate Army, Private H. B. Robinson sat down to record his thoughts about his combat experience.

The words that flowed from his pen produced the following poem, which is being reprinted here through the generosity of Horace’s descendant, Amy Maurer:

THE BATTLE OF CEDAR CREEK, 1864

On the 19th of October while Sheridan was away

The bloody fight was opened just at break of day

On the right three volleys sounded, on the left began the boom

And the rattle of the musketry spoke many a brave man’s doom

The soldiers in their tents were peacefully reposed

But by the canons’ thundering were hastily aroused

To arms! to arms! we heard brave Thomas say

Then to the Eighth Corp’s camp he hurried us away

The line moved on, heedless of the running crowd

Till they met in deadly conflict where the battle sounded loud

Ten minutes did the work for McMillan’s old Brigade

And they were hurried back by the rebel Kershaw’s raid

The colors there were knocked from the color Sergeant’s hand

But were very quickly raised at Oyster’s stern command

Again the colors fell and the second bearer reeled

So the Major told brave Pratt to leave the bloody field

Then Oyster grasped the colors–the balls flew thick around

One of which was fairly aimed and brought him to the ground

The colors did not fall but were held high up in the air

Till they were seized by Feeley, a man who knew no fear

“Don’t give up the colors” was Oyster’s parting word

“I’d rather see them burned” said he “Than possessed by rebel horde”

The men who heard the captain make this last request

Resolved to fight beneath its fold if needs be sink to rest

Two companies yet remained to bear the battle’s brunt

They now were fiercely charged by Kershaw’s right and front

On the left Ramseur by his tremendous sway

Quickly forced the last of McMillan’s old Brigade away

At the bayonet’s point he left the bloody stand

And began the sad retreat at Lynch’s stern command

The distance was but short, when a line was quickly formed

Here they fought most bravely and twice were fiercely stormed

But now they are no longer able to face the foe

And from their fiery lines are paying a fearful toll

Soon the voice of General Emery, a clear and manly tone

Announced the welcome tidings “Phil Sheridan has come”

A wild hurrah burst forth from all the brave but beaten men

And Sheridan today will soon our camp regain

The lines reformed and an effort then was made

To stop for once and all the furious rebel raid

Charge! charge! charge! rang out loud and long

As the Federal line moved forward on the Confederate throng.

Sly Early in his turn was forced to yield away

Before our Springfield rifles and the canon’s deadly play

Their flight was then more hurried than it ever was before

For they learned much to their sorrow of the fight in Brick Top’s Corps

Brave Custer and his men were somewhere there about

And they burst forth upon them with a wild and deafening shout

Every eye was glaring wildly, every saber raised on high

Every man was in his saddle for to conquer or to die

And many a bleeding hearts in the last desperate fray

Grew cold, its last thought turning to the loved ones far away

When the camp had been regained, the weary stopped to rest

For the arms of brave Phil Sheridan God with victory had blessed.

Just fifteen years old when he wrote those words, Private H. B. Robinson had not only had the presence of mind and skill to survive the intensity of a battle that wreaked havoc on his regiment, but had demonstrated his strength of heart and hard-earned wisdom by preserving for posterity all that he had heard and seen that day when the 47th Pennsylvania lost nearly two full companies of men (killed, wounded, missing in action, or captured by Confederate troops).

Soldiering On

Ordered to move from their encampment near Cedar Creek, Private H. B. Robinson and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched to Camp Russell, a newly-erected, temporary Union Army installation that was located south of Winchester, just west of Stephens City, on grounds that were adjacent to the Opequon Creek. Housed here from November through 20 December 1864, they remained attached to the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah.

Five days before Christmas, he and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians were on the move again — this time, marching through a snowstorm to reach Camp Fairview, which was located just outside of Charlestown, West Virginia. Following their arrival, they were assigned to guard and outpost duties.

1865

Still stationed at Camp Fairview as the old year gave way to the new, Private H. B. Robinson learned that his military tenure was about to end sooner than anticipated. On 24 January 1865, he was honorably discharged by the U.S. War Department, due to his status as an underage minor, and was sent home.

Return to Civilian Life

Following his honorable discharge from the military, H. B. Robinson returned to Juniata County, Pennsylvania, where he resumed life with his parents and siblings on the family farm, which was located near Port Royal in Milford Township. By 1870, the Robison/Robinson household included patriarch John Robison, whose personal property and real estate were valued by that year’s federal census enumerator at more than forty-six thousand dollars (the equivalent of more than one million U.S. dollars in 2025); family matriarch Sarah Robison; twenty-three-year-old Thomas Robison, who was documented as “attending school” that year; twenty-one-year-old H. B. Robison, who was listed as “Brady” and was documented as being employed as a teacher; nineteen-year-old Clara Robison, who was also documented as being employed as a teacher; seventeen-year-old John Robison, Jr.; and their younger siblings Mary, Grace, Maude, and Benton Robison.

In 1871, H. B. Robinson enrolled in the civil engineering program at Cornell University. He graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in Civil Engineering in June 1874.

During this same period of time, his younger sister, Clara Robison was a student in “School No. 2” of the Mifflintown School system in Juniata County. Her teacher was J. E. Nolan. According to an 1874 edition of the Juniata Sentinel and Republican, she was “present at every roll-call” during the month of February 1873. The academic achievements of his younger sisters, Mary Genevieve and Sarah Grace Armstrong Robison, were also recognized in June of that same year (1873) when both were awarded silver medals for scholarship by the Tuscarora Female Seminary at its annual commencement exercises.

In 1875, their older brother, Thomas Alexander Robinson, was ordained as a minister in the Presbyterian Church. He was subsequently posted to a position as the pastor of a church in the village of Hebron, Illinois. Sadly, that same year, their younger brother, Jesse Benton Robison, died at the age of eleven. Just two months shy of his twelfth birthday, Benton was buried at the Lower Tuscarora Church Cemetery. In 1876, the Rev. Thomas A. Robinson wed Ella T. Wilson.

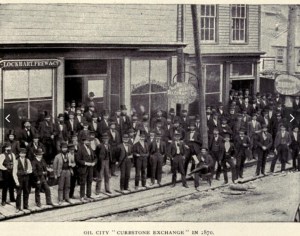

The “Curbstone Exchange” in Oil City, Pennsylvania, 1870 (McLaurin, John J. Sketches in Crude Oil Illustrated, 1902, public domain).

Meanwhile, H. B. Robinson was also making a name for himself professionally; employed as the assistant engineer for the Cincinnati and Eastern Railroad from 1876 to 1877, he was then hired by the City of Oil City in Venango County, Pennsylvania to serve as its city engineer–a position he held from 1878 to 1881, according to Cornell University alumni records.

Around this same time, according to Franklin, Pennsylvania’s News-Herald, he was hired by the United Pipe Line Co. of Franklin, Pennsylvania in January 1878. Recruited and promoted by the American Transfer Company in 1879, he was “placed in charge of surveys, plans and construction of the Cleveland pipe line, the first long pipe line to be built by [that company].”

Sometime around 1880, H. B. Robinson’s younger sister, Mary Genevieve Robinson, wed New Jersey native Charles H. Burtis. Sent to Bradford, Pennsylvania by the National Transit Company in 1881, H. B. subsequently worked on a number of different projects there over the next several years.