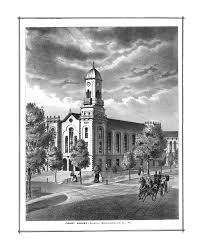

The Court House in Sunbury, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, was most likely where Charles L. Marshall enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers as “Thomas Lothard” (circa 1850s, public domain).

Charles L. Marshall is one of the “mystery men” of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Union Army clerks who entered his name on regimental muster rolls noted that he was a Pennsylvanian who enlisted for military service in Sunbury, Northumberland County while records created later in his life by local, state and federal officials indicated that he was born in Virginia.

What researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story have determined for certain is that he enlisted for Civil War military duty at the age of 19 using the alias of “Thomas Lothard.”

Now, thanks to the digitization of his 1918 death certificate, more details about his life are finally coming to light.

Formative Years

Born in Virginia in 1841, Charles L. Marshall was a son of Virginia natives Charles and Lula Marshall. Employed as a miner at the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, he was a resident of Luzerne County, Pennsylvania at that time.

American Civil War

Rather than enlisting near his hometown in Virginia or joining a Union Army unit near the site of his workplace in Pittston, Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, Charles L. Marshall chose to enlist for military service on 19 August 1861 in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania (nearly eighty miles away), and he chose to do so under an assumed name. Why he made both of those decisions remains a mystery.

Most likely enrolled at the courthouse building in Sunbury, Northumberland County, Charles L. Marshall officially mustered for duty as Private Thomas Lothard with Company C of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Captain Hastings processed his paperwork at Camp Curtin, Harrisburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania on 2 September 1861.

* Note: Known more commonly as the “Sunbury Guards, Company C was a military unit with an already distinguished history. Established initially as a small town militia group, the Sunbury Guards had, according to several historians, protected the United States of America in every major military engagement since the American Revolution. By the time Charles Marshall enlisted, the Sunbury Guards had further distinguished itself as the first of Northumberland’s militia units to respond to President Abraham Lincoln’s 15 April 1861 call for seventy-five thousand volunteers “to maintain the honor, the integrity, and the existence of our National Union.” Fighting as part of Company F, 11th Pennsylvania Volunteers at Falling Waters, Martinsburg and Bunker Hill, Virginia, the Sunbury Guards mustered out honorably in July 1861. Most, within weeks of their return, re-nrolled for three-year terms with Company C, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

Military records at the time of enlistment by Charles L. Marshall/Thomas Lothard in August 1861 described him as being five feet, three inches tall with black hair, black eyes and a dark complexion. Later records place his height at five feet, eight inches tall.

While at Camp Curtin, Private Thomas Lothard received training with the 47th Pennsylvania in light infantry tactics before being transported with his regiment to Washington, D.C. Stationed roughly two miles from the White House, at “Camp Kalorama” on the Kalorama Heights near Georgetown beginning 21 September, Lothard and the other 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were mustered into federal service with the U.S. Army with great ceremony on 24 September 1861.

Assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith’s Army of the Potomac on 27 September, and armed with Mississippi rifles supplied by their beloved Keystone State, the 47th was given marching orders to head for Camp Lyon, Maryland on the eastern side of the Potomac River. Arriving during the late afternoon, they joined the 46th Pennsylvania in marching double-quick across a chain bridge before marching on toward Falls Church, Virginia.

Arriving at Camp Advance around dusk, Private Thomas Lothard and his fellow Sunbury Guards/Company C pitched their tents in a deep ravine near Fort Ethan Allen, a new federal military facility still under construction. Here, as part of the 3rd Brigade and Brigadier-General Smith’s Army of the Potomac, they helped to defend the nation’s capital.

On 11 October, after having been ordered with the 3rd Brigade to “Camp Big Chestnut” (so named because of a prominently located chestnut tree and later renamed as Camp Griffin), the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads.

In a letter home in mid-October, Thomas Lothard’s commanding officer, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin, reported that the right wing of the 47th Pennsylvania (companies A, C, D, F and I) was ordered to picket duty after the left wing (companies B, G, K, E, and H) was forced to return to camp by Confederate troops.

On Friday morning, 22 October 1861, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers participated in a Divisional Review, described by historian Lewis Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.”

Half of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, including Company C, were next ordered to join parts of the 33rd Maine and 46th New York in extending the reach of their division’s picket lines, which they did successfully to “a half mile beyond Lewinsville,” according to Gobin. On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review by Colonel Tilghman H. Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.”

Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.” As a reward, Brannan obtained new Springfield rifles for every member of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

1862

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were transported to Florida aboard the steamship U.S. Oriental in January 1862 (public domain).

Next ordered to move from their Virginia encampment back to Maryland, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862. Marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church, they were transported by rail to Alexandria, and then sailed the Potomac via the steamship City of Richmond to the Washington Arsenal, where they were reequipped before they were marched off for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington, D.C. The next afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvanians hopped railcars on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland. Arriving around 10 p.m., they were assigned quarters in barracks at the Naval Academy. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship Oriental.

By the afternoon of Monday, 27 January 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had commenced boarding the Oriental. Ferried to the big steamship by smaller steamer, the enlisted men boarded first, followed by the officers. Then, per the directive of Brigadier-General Brannan, the Oriental steamed away for the Deep South at 4 p.m. They were headed for Florida which, despite its secession from the Union, remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Key West and the Dry Tortugas.

Woodcut depicting the harsh climate at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida during the Civil War (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

In early February 1862, they arrived at Fort Taylor in Key West. On 14 February, the regiment made itself known to area residents via a parade through the city’s streets.

On garrison duty, they drilled daily in military strategy, including heavy artillery tactics. Their time was made more difficult by the presence of tropical diseases, as well as the always likely dysentery from soldiers living in close, unsanitary conditions.

Next ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina from mid-June through July, they camped near Fort Walker and then quartered in the Beaufort District, Department of the South. Frequently assigned to hazardous picket detail north of their main camp, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers became known for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing,” and “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan,” according to historian Samuel P. Bates.

On 30 September 1862, C Company and the 47th Pennsylvania were sent back to Florida where they participated with Union troops in capturing Saint John’s Bluff from 1 to 3 October. Under the command of Brigadier-General Brannan, the fifteen-hundred-plus Union force left their gunboat-escorted troop carriers at Mayport Mills and Mount Pleasant Creek. On point with the 47th Pennsylvania and braving alligators, snakes and Rebel troops, the men pushed through twenty-five dense miles of forests and swamps to capture the bluff and pave the way for the Union’s occupation of Jacksonville, Florida.

Highlighted version of the U.S. Army map of the Coosawhatchie-Pocotaligo Expedition, 22 October 1862 (public domain).

From 21-23 October, Company C and the 47th engaged Confederate forces in the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina. Landing at Mackay’s Point under the brigade command of 47th Pennsylvania founder, Colonel Tilghman H. Good, and regimental command of Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, the 47th led the way once again.

This time, however, the luck of Private Thomas Lothard and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers ran out. Bedeviled by snipers, the brigade faced resistance from an entrenched Confederate battery and withering fire as they entered an exposed cotton field. Those headed for the Frampton Plantation’s higher ground were pounded by artillery and infantry secreted away in the surrounding forests. Undaunted, they charged and forced the Rebels into a four-mile retreat to the Pocotaligo Bridge. At this juncture, the 47th relieved the 7th Connecticut but, after two hours of exchanging fire while attempting to take the ravine and bridge, the 47th ran low on ammunition, and withdrew to Mackay’s Point.

Two officers and eighteen enlisted men from the 47th were killed during the expedition, including Private Seth Deibert; two officers and one hundred and fourteen enlisted men were wounded, including Private Thomas Lothard, who had been shot in the head. Treated behind the lines, he was transported back to Hilton Head, where he received more advanced care at the Union Army’s post hospital there.

1863

By 1863, Captain J. P. S. Gobin and the men of C Company were once again based with the 47th Pennsylvania in Florida. Having been ordered back to Key West on 15 November, they spent 1863 at Fort Taylor with Companies A, B, and D while Companies E through K were sent to garrison Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas.

While here, Private Thomas Lothard was discharged per General Order 191 on 11 October 1863 at Fort Taylor, Key West, Florida. He then promptly re-enlisted for another three-year term of service, earning the coveted designation of “Veteran Volunteer.”

1864

On 25 February 1864, Private Thomas Lothard and the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers began a phase of service during which the regiment would make history. Boarding the steamer Charles Thomas, he and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers traveled from New Orleans to Algiers, Louisiana. Arriving on 28 February, they then traveled by train to Brashear City before moving to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union General Nathaniel P. Banks.

From 14-26 March, the 47th passed through New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington while en route to Alexandria and Natchitoches. Often short on food and water, the regiment encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day, marching until mid-afternoon.

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division, sixty members of the 47th were cut down on during the back-and-forth volley of fire during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (also known as the Battle of Mansfield). The fighting waned only when darkness fell. Exhausted, the uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded and the dead. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill.

C Company’s Private Jeremiah Haas was one of the many killed; Private Thomas Lothard was one of the even larger number wounded. Lothard had been shot again in the head, this time suffering a gunshot wound to the top of his head; he had also been shot in the side and left shin.

As his regiment continued the fight the next day at Pleasant Hill, Sunbury Guardsman and sixty-eight-year-old Company C Color-Sergeant Benjamin P. Walls and Sergeant William Pyers were wounded during the Battle of Pleasant Hill. Many died; many more were wounded; still others were taken prisoner, and held in substandard Confederate prison camps until released during a prisoner exchange on 22 July 1864.

Due to his battle injuries, Private Lothard would almost certainly not have taken part in the fight at Pleasant Hill, and was also likely “on the sidelines” when his regiment fought again on 23 April in the Battle of Cane River near Monett’s Ferry. And he may also have still been recuperating from 30 April to 10 May, when his regiment was involved in erecting a timber dam across the Red River to enable Union gunboats to travel more easily to and from the mighty Mississippi River.

Depending on the severity of his injuries, he may not even have been involved with the regiment’s march toward New Orleans.

New Orders

Battered by the Bayou but undaunted, and leaving behind the grievously wounded and seriously ill who were convalescing from the various diseases they had contracted during their lengthy Louisiana expedition, the majority of men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I sailed for Washington, D.C. via the steamer McClellan beginning 7 July 1864.

Following their arrival in Virginia and a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln, they then joined Major-General David Hunter’s forces at Snicker’s Gap in mid-July where they assisted, once again, in defending the nation’s capital while also helping to drive Confederate forces from Maryland.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Attached to the Middle Military Division, U.S. Army of the Shenandoah from August through November 1864, it was at this time and place, under the leadership of legendary Union General Philip H. Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, that Private Thomas Lothard and his fellow members of the 47th Pennsylvania would engage in their greatest moments of valor. Of the experience, Company C’s Samuel Pyers said it was “our hardest engagement.”

Inflicting heavy casualties during the Battle of Opequan (“Third Winchester”) on 19 September 1864, Sheridan’s gallant blue jackets forced a stunning retreat of Jubal Early’s grays—first to Fisher’s Hill (21-22 September) and then, following a successful early morning flanking attack, to Waynesboro. These impressive Union victories helped Abraham Lincoln secure his second term as President.

On 19 October 1864, Early’s Confederate forces briefly stunned the Union Army, launching a surprise attack at Cedar Creek, but Sheridan was able to rally his troops. Intense fighting raged for hours and ranged over a broad swath of Virginia farmland. Weakened by hunger wrought by the Union’s earlier destruction of crops, Early’s army gradually peeled off, one by one, to forage for food while Sheridan’s forces fought on, and won the day.

Although the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers sustained heavy casualties during Sheridan’s campaign, Private Thomas Lothard appears to have survived unscathed. Stationed at Camp Russell near Winchester, Virginia from November through December, the men mourned their dead and recuperated from their injuries. Five days before Christmas, they were ordered to march again—this time, for outpost duty at Camp Fairview in Charlestown, West Virginia.

1865

Spectators gather for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, beside the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half-mast following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Assigned first to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Army of the Shenandoah in February 1865, Private Thomas Lothard and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered back to Washington, D.C. 19 April to defend the nation’s capital again, following the assassination of President Lincoln.

Letters home from several members of the 47th and later media coverage confirm that at least one member of the regiment was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train while others from the 47th Pennsylvania were assigned to guard duty at the prison where the Lincoln assassination conspirators were held and tried.

Attached to Dwight’s Division, 2nd Brigade, U.S. Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania also marched in the Union’s Grand Review on 23-24 May.

On its final swing through the South, the 47th served in Savannah, Georgia from 31 May to 4 June 1865 as part of the 3rd Brigade, Dwight’s Division, U.S. Army Department of the South, and at Charleston and other parts of South Carolina beginning in June.

Mistakenly Labeled as a Deserter

Although a muster roll indicates that Private Thomas Lothard deserted at Savannah, Georgia on 5 July 1865, the entry made by “Cap Bowers” was made in error. The confusion may have resulted from the gunshot wounds to the head that Charles L. Marshall sustained twice in battle, the often sloppy record keeping by Union Army personnel who failed to properly identify wounded soldiers admitted to Union hospitals, and/or the confusion over the alias used at his time of enlistment (“Thomas Lothard”) versus his real name (“Charles L. Marshall”).

More than a decade later, that ledger entry was modified in April 1887 with a handwritten notation in red ink indicating that the War Department had re-investigated his case. Private Thomas Lothard’s listing in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania also contains a notation to this effect: “Re-enlisted 10-12-63. Correct Name: Marshall, Charles L. See Circular from Washington Dated 4-9-87.”

Further confirming that there was no desertion, a Civil War Pension Index entry indicates that a pension application was filed by the veteran as “Charles L. Marshall” with the alias of “Thomas Lothard” in 1892 from Kansas. Additionally, he received care and pension payments at the U.S. National Home for Disabled Union Soldiers in Leavenworth, Kansas in later years, and was buried at the Marion National Cemetery in Marian, Indiana—all actions by the federal government which would not have occurred had he truly been a deserter.

Honorable Discharge from the Military

A 1915 Grand Army of the Republic entry for Charles L. Marshall notes that he was discharged from service on 7 January 1866; however, entries for him in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives and U.S. National Home for Disabled Union Soldiers at Leavenworth place the discharge date as 3 July 1865. That Soldiers’ Home entry also noted that his discharge was granted at the “Close of War” at Washington, D.C., possibly signaling that he had been hospitalized before or at the time of discharge.

What Actually Happened to Charles Marshall After He Returned to Civilian Life?

Post-war, Charles Marshall shed his assumed name of “Thomas Lothard.” Multiple documents, including state and federal census records confirm this fact; therefore, it appears that whatever had caused him to adopt an alias no longer appeared to be an issue. He also appears not to have returned to Pennsylvania or Virginia for any length of time, however; he chose, instead, to make his way west.

For the remainder of his life, though, he would battle persistent health issues related to the wounds he had sustained during the war. By the turn of the century, his health was much worse.

On 7 October 1905, Charles L. Marshall was admitted to the Western Branch (Leavenworth, Kansas) of the network of U.S. National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. Dropped from the roster by General Order H33 on 7 May 1906, he was readmitted to the same branch home on 27 September 1907, where he remained until checking out under his own authority in March 1908.

Soldiers’ Home records indicate that his residence subsequent to discharge was Topeka, Kansas, that he was a widower, and that his nearest living relative was Cyrus Heurrel (sp?) in Granada, Kansas. A Protestant by faith and laborer by trade at the time of his first Soldiers’ Home admission, the ledger confirms that he was wounded multiple times in battle:

- G.S. Wound Head, Wounded Oct 22 – 1862, Pocotaliga [sic] S.C.; and

- G.S. wound right side, left shin & top of head.

Based on other records, it appears that the second set of gunshot wounds was incurred on 8 April 1864 during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield, Louisiana. Other complaints detailed on the medical ledger entry (likely due to aging but also possibly developed due to his having been wounded in action), were: “Prostatic hyper,” lumbar, myalgia, and “chr. cystitis.”

On 5 March 1910, Charles L. Marshall was again readmitted to the Soldiers’ Home at Leavenworth, Kansas, and remained there until checking out under his own authority on March 1911. This pattern repeated as follows:

- Admitted 15 March 1912, checked out 2 January 1914;

- Admitted 14 November 1914, checked out 17 March 1915; and

- Admitted 24 July 1915, checked out 21 March 1916.

During 1915, while residing at the Soldiers’ Home in Leavenworth, Charles L. Marshall served as a member of the Grand Army of the Republic, Gen. U.B. Pearsall Post No. 500. Aged 72 at the time, his former occupation was listed as “Clerk.”

On 8 August 1916, he was again admitted to the Soldiers’ Home at Leavenworth, and checked out again on his own authority on 17 October of that same year. The pattern repeated yet again with Charles Marshall being granted admission to the U.S. National Soldiers’ Home at Leavenworth Kansas on 17 January 1917. He remained there until checking himself out on 10 October 1918.

Based on information contained in his death certificate, it appears that he had traveled to Indiana shortly thereafter, and was admitted, within a few short weeks of his arrival, to the U.S. Soldiers’ Home in Marion, Indiana on 23 October 1918. Diagnosed there with hypertension and cystitis, he died on 31 October 1918. His federal burial ledger supports this data, listing both his given name, “Charles L. Marshall,” and his alias “Thomas L. Lothard,” as well as his service with Company C of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

In addition, it contained the following notation: “Remains taken to Receiving Dis, Ind for Burial.”

Questions about his seemingly itinerant existence were finally answered by his soldiers’ home admissions records and his death certificate. A cattleman by trade, he had lived in multiple states after the war, including Kansas and New Mexico before spending his final days in Indiana. Grievously injured in battle multiple times, he suffered from multiple chronic health problems that were compounded by aging-related issues, all of which were exacerbated by living the grueling life of a cattleman.

Final Resting Place

Finally, after serving his nation faithfully, on 2 November 1918, this old soldier, who d chosen to join the fight to preserve his nation’s Union, rather than support secession by his state of birth, was laid to rest at the Marion National Cemetery in Section 4, Row 9, Grave Number 2716 in Marion, Indiana.

The name inscribed on his marker was “Charles L. Marshall.”

Sources:

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Burial Ledgers (Charles L. Marshall/Thomas Lothard), The National Cemetery Administration, U.S. Departments of Veterans Affairs (Record Group 15), Defense, and Army (Quartermaster General, Record Group 92). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Civil War Muster Rolls and Related Records (Thomas Lothard), Pennsylvania Department of Military and Veterans’ Affairs (Record Group 19, Series 19.11). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

- Civil War Veterans’ Card File (“Lothard, Thomas”). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Grand Army of the Republic, Department of Kansas, Post Records (Bound Manuscript Collection 126 (Charles L. Marshall, Gen. U.B. Pearsall Post No. 500, 1915). Topeka, Kansas: Kansas Historical Society.

- Historical Register of National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (Western Branch/Leavenworth, Kansas: Charles L. Marshall, alias Thomas Lothard; Record Group 15, Microfilm M1749). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Charles L. Marshall” (death certificate, file no.: 32348, registered no.: 39; death date: 31 October 1918. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana State Board of Health.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

You must be logged in to post a comment.