A grandson of a twice-wounded veteran of the American Civil War and the youngest child of a telephone industry pioneer, Willard Emery Snyder began his work life as an employee of a communications company that was co-founded by his father.

A veteran of World War II, he helped to install and maintain telephone and telegraph cables, lines and other equipment in Africa and the Pacific Theater of operations before embarking on a nearly thirty-year career with the Bell Telephone Company of Pennsylvania and raising a family in the Great Keystone State.

Formative Years

Born on 31 July 1917 in the Village of Lavelle, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, Willard Emery Snyder was the eighth child born to John Hartranft Snyder and Minnie Rebecka (Strohecker) Snyder. His mother, Minnie, was the daughter of Samuel and Annie (Troutman) Strohecker, of the town of Gordon in Schuylkill County. His father, John, was the first surviving son of Catharine (Boyer) Snyder and Timothy Matthias Snyder, who had served with the color-bearer unit (Company C) of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry during the American Civil War.

* Note: The middle name of Willard Snyder’s father “Hartranft,” was first used in this branch of the Snyder family when Willard’s grandparents, Timothy Matthias Snyder and Catharine (Boyer) Snyder, made the decision to give each of their male children middle names that honored the Union Army generals that Tim had served under and respected during the American Civil War. “Hartranft” was the surname of Major-General John Frederick Hartranft, the Union Army officer who was placed in charge of the federal prison where the key conspirators in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln were held during their imprisonment and trial. (Major-General Hartranft was also the Union Army officer who read the execution warrant to the subsequently convicted conspirators shortly before their hanging at that prison. Post-war, Hartranft was elected as the seventeenth governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.)

The name of “Emery,” which was given to Willard E. Snyder, the subject of this biography, was a middle name that Willard shared with his paternal uncle, William Emery Snyder (1885-1944), the youngest son of Timothy Matthias Snyder and the youngest brother of John Hartranft Snyder. It was a spelling variant of “Emory,” the surname of Brigadier-General William Hemsley Emory, the commanding officer of the Army of the United States’ 19th Corps in Louisiana and Virginia in 1864. (Timothy M. Snyder had been a private serving with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers in Louisiana under Emory during the spring of that year and a corporal serving with the 47th Pennsylvania in Virginia during that summer and fall.)

Although Willard E. Snyder never had the opportunity to meet his Civil War veteran grandfather in person, he was still close enough, chronologically, to feel as if he had. Cradled in the arms of his paternal grandmother, Catharine (Boyer) Snyder, who died a year after he was born, Willard grew up hearing stories about his Civil War veteran grandfather from his father and older siblings (who had all been born early enough to interact with their paternal grandmother during their elementary/high school years). In addition, Willard knew and interacted with his paternal uncles and aunt, Timothy Grant Snyder (1876-1925), William Emery Snyder (1885-1944) and Lillie May Snyder (1887-1956), who had all grown up hearing their father’s stories, firsthand, about his experiences during the American Civil War.

In addition to an early childhood shaped by reliable accounts of what the American Civil War had really been like for the Pennsylvanians who lived through it, Willard Snyder spent his formative years as a member of a household that had been transformed by two tragedies. By the time that he opened his eyes for the first time in Lavelle, his family had survived the 1911 destruction by fire and rebuilding of the family’s home and had then also endured the tragic death of his oldest brother, Timothy Peter Snyder (1898-1913), who had been killed in a work-related accident at the Potts Colliery in nearby Locustdale on 22 April 1913.

Willard E. Snyder’s older sister, H. Corrine Snyder, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, circa 1930s, who was nicknamed “Eenie” (Snyder Family Archives, used with permission).

As the youngest child of a large family, Willard’s world was also one that taught him that a person’s age and gender had no bearing on an individual’s ability to succeed. Both of his parents were in their mid-forties when he was born and both had been successful business owners. And his oldest siblings — Nona Mae Snyder (1900-1987), Helen Corrine Snyder (1901-1988), John Sylvester Snyder (1904-1969), Catharine Rebecka Snyder (1906-1995), Chester Hartranft Snyder (1910-1983), and Lillian Estelle Snyder (1908-2001), were all already enrolled in or completing their education in Schuylkill County’s public school system.

* Note: Nine years before Willard was born, his father, John Hartranft Snyder, had co-founded the Lavelle Telegraph and Telephone Company. Officially incorporated in 1908, the company’s main communications center was based at the Snyder family home on Main Street in Lavelle, which was located directly across the street from the Lavelle School. John H. Snyder, would later be credited with installing the first telephone lines in the Lavelle Valley, as well as in rural areas south of the city of Ashland in Schuylkill County.

In addition, Willard Snyder’s mother, Minnie, operated a dry goods store from the ground floor of the family’s home, with help from his oldest sisters, Nona and Corrine, with whom he would forge a close bond. Largely responsible for raising Willard while their parents managed the family’s businesses and kept the family afloat during an increasingly challenging economy, Willard was the person who created Corrine’s nickname. Unable to pronounce her name (as Koh-REEN) when he was just a toddler, he had called her “Eenie,” a beloved moniker for the greatly loved sister and aunt (that was used even by longtime friends who thought it suited her kindhearted nature).

1920s — 1930s

By 1920, Willard Snyder was residing at home in Lavelle with his parents and siblings: Nona, Corrine, John S., Catharine R., Lillian E., and Chester H. Snyder. According to that year’s federal census, Nona was a nineteen-year-old “saleslady” in a clothing store, and was the only one of her siblings who was employed at that time. Their father, John H. Snyder, was described as a carpenter who was employed in the “coal mines.” It would prove to be a memorable year for his mother and aunts because they and other women across the United States of America, who were twenty-one years of age or older, were finally granted the right to vote, following the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution on 18 August 1920.

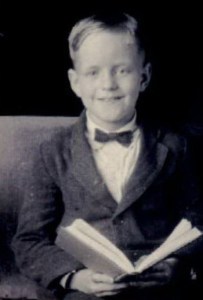

Willard Emery Snyder, shown here at the age of nine in 1926, gave Corrine Snyder the nickname of “Eenie” (Snyder Family Archives, used with permission).

By the mid to late 1920s, Willard’s older brother, Ches, was graduating from Ashland High School, while their three sisters, Eenie, Catharine (who was known as “Kitty” or “Kit”) and Lillian, had moved out of the Snyder family home in Lavelle and had relocated to the city of Reading. Both Eenie and Kitty, who had been working as a bookkeeper and a stenographer, respectively, had been living together in an apartment at 1037 North 4th Street in Reading when Lillian moved in with them during the winter of 1927 in order to pursue training at the Reading Hospital School of Nursing. Following her graduation on 9 May 1929, Lillian was appointed to the nursing faculty and clinical staff of the Reading Hospital. Sometime around this same time, Willard Snyder’s older brother, John Sylvester Snyder, had relocated to Mount Carmel in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania. By 1928, John S. Snyder was employed there as a construction estimator and superintendent of construction for the E. R. Bastress Company.

Through it all, Willard Snyder had diligently been attending to his studies at the Lavelle School — directly across the street from his house. A good student, he enjoyed reading, math, science, and history.

But once again, the strength of the Snyder family would be tested — this time when a major reversal of fortune shook their community, state and nation during the fall of 1929. Between 28 and 29 October of that unstable year, the Dow Jones (America’s stock market) suffered a twenty-five percent loss, sparking a worldwide financial disaster that would ultimately come to be known as the Great Depression. “By mid-November, the Dow had lost almost half its value,” according to historians at the United States Federal Reserve.

The slide continued through the summer of 1932, when the Dow closed at 41.22, its lowest value of the twentieth century, 89 percent below its peak. The Dow did not return to its pre-crash heights until November 1954.

By 1930, Willard Snyder was still living at his parents’ home in Lavelle. Also living there were Willard’s older siblings: Nona M. Snyder, who was unmarried and unemployed (due to the Great Depression); and John Sylvester Snyder, who was unmarried but employed as a laborer at a lumber company. Also bringing in much-needed income was Willard’s father, who was described by that year’s federal census enumerator as a coal mine laborer.

* Note: During this same time, Willard Snyder’s older brother, Ches Snyder, was still single and living nearby in Ashland while working for the company that their father had co-founded — Lavelle Telegraph and Telephone. That same year, a census enumerator in neighboring Berks County confirmed that Eenie, Kit and Lillian Snyder (Willard Snyder’s other older siblings), were still living and working in the city of Reading. Eenie was a bookkeeper employed by the Jewel Tea Company, Kit was a stenographer working for the Reading Iron Company, and Lillian was a registered nurse serving on the faculty of the Reading Hospital School of Nursing.

Despite the persistence of economic uncertainty throughout the 1930s, multiple Snyder siblings still managed to make multiple, forward-thinking changes to their lives — forging new paths that they hoped and prayed would lead them toward brighter days. On 3 June 1931, John Sylvester Snyder wed Catherine M. Rissmiller (1906-1996) in Gordon, Schuylkill County. Known to family and friends as “Kitty,” she was a daughter of Albert and Emma Rissmiller. Then, on 15 June 1933, Ches Snyder wed Roma May Haas (1914-2003). A daughter of Palmer C. Haas and Mayme J. (Dietz) Haas of Pitman, Schuylkill County, she was known to family and friends as “May.”

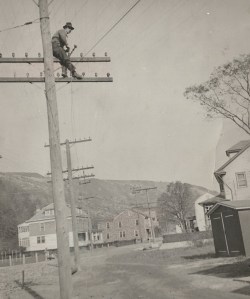

Willard Emery Snyder at work in 1938, Millersville, Pennsylvania (U.S. Works Progress Administration and Snyder Family Archives, used with permission).

A student at Ashland High School in Ashland, Schuylkill County between 1931 and 1935, Willard Snyder kept busy with his studies in algebra, chemistry, German, music, physics, and woodshop. A member of his school’s basketball team, he also enjoyed ice skating and numismatics (the collection and study of coins), and became a skilled, classical pianist who performed in area recitals. After graduating from Ashland High School in June of 1935, he entered the workforce later that same month as an employee of his father’s company, Lavelle Telegraph and Telephone.

Employed by the U.S. Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1938, he was photographed by the WPA while working atop a telephone poll in Millersville, Pennsylvania in mid-October.

1940s

Still employed by Lavelle Telegraph and Telephone during the early 1940s, Willard E. Snyder worked as a “Combination Man” whose duties involved the installation of magneto-type telephones and telephone lines, as well as troubleshooting and repair work in rural communities, during which he functioned as the supervisor of a four-man crew of linemen. A hard worker, he was paid just twenty-five dollars per week (equivalent to an annual salary of roughly twenty-seven thousand U.S. dollars in 2025).

Hired by the Bell Telephone Company of Pennsylvania in August of 1941, he was based out of the company’s facility at 103 Lancaster Avenue in Reading, and initially worked as an assistant cable splicer for the company’s outside plant department, performing preventive, troubleshooting and maintenance work in Schuylkill and Berks counties that involved identifying and repairing trouble spots along telephone cables, cable splicing and “boiling out” wet cables.

Brothers Willard, Chester, and John Sylvester Snyder, Lavelle, Pennsylvania, circa 1940 (Snyder Family Archives, used with permission).

While continuing to work for Bell Telephone’s outside plant department during the summer of 1942, he resided with his older sister, Eenie Snyder, at her apartment at 713-1/2 North 5th Street in the city of Reading. On 17 June of that year, he enlisted with the United States Navy. Military records at the time described him as a twenty-four-year-old who weighed one hundred and sixty-five pounds and was five feet, six and one-half inches tall with blonde hair, blue eyes and a light complexion.

After saying his goodbyes to his sister in September, he packed a few of his belongings and headed for Rhode Island, where he had been ordered to report for basic training.

World War II Naval Service

Willard Emery Snyder began his World War II-era basic training at the U.S. Naval Construction Training Center (USNCTC) in Davisville, Rhode Island on 28 September 1942. Located roughly eighteen miles south of the city of Providence, naval personnel at the USNCTC “specialized in training the Navy’s Construction Battalions, or ‘Seabees,’ to meet the challenges of building new bases, often in remote overseas areas,” according to military historians of the U.S. Navy.

After completing his training at the USNCTC on 11 December 1942, Willard E. Snyder was then assigned to the U.S. Naval Reserves’ Construction Battalion Detachment 1002 (a branch of the “Seabees”) as an electrician’s mate on 11 December 1942. Transported by ship to Gourock, Renfrewshire, Scotland, he remained there with his unit until 31 December of that same year, when he traveled with his unit by ship to what was then British West Africa. Arriving in early January 1943, he was stationed in Freetown, Sierra Leone in British West Africa (now Freetown, Sierra Leone) with the U.S. Naval Reserves’ Construction Battalion Detachment 1002 and assigned to guard and general detail duties until 31 March 1943, when he was transferred to the United States Naval Reserves’ 65th Construction Battalion (also part of the “Seabees”). Assigned to guard and general detail duties with the 65th Construction Battalion in and around Freetown, he served there with his unit until early June 1943, when he was transported by ship back to Boston, Massachusetts in the United States.

Subsequently enrolled in the carbine and submachine gun marksmanship program and the communications school at the U.S. Navy’s Naval Construction Training Center (NCTC) in Davisville, Rhode Island, beginning on 13 and 25 August 1943, respectively, he was then also enrolled in the NCTC radio and telephone communications training program in Davisville on 8 September 1943.

Willard Emery Snyder, U.S. Navy Seabees, Hawaiian Islands, circa 1943 (Snyder Family Archives, used with permission).

After completing his training, he was transferred to the U.S. Naval Reserves’ Construction Battalion Maintenance Unit 530 (CBMU 530) on 21 September 1943, and was subsequently transported with his unit to the Port Hueneme Air Base in Ventura County, California on 24 September. Stationed at Port Hueneme until 25 October, he and his unit were then transported north to San Francisco, where they boarded the USS Prairie with hundreds of other officers and enlisted members of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps. On 15 November, they headed out to sea. He was bound for Marine Corps Air Station Ewa (MCAS) Ewa. The “forward Marine Corps airfield in the Hawaiian Islands during World War II,” according to the Historic Hawai’i Foundation, it was located on the island of Oahu, roughly seven miles west of Pearl Harbor, and “became known to Marine aviators as their ‘Crossroads of the Pacific.'”

Upon his arrival at MCAS Ewa, Electrician’s Mate Willard Snyder was initially assigned to duties as an outside electrical lineman. Promoted up through the ranks of CBMU 530, he was reassigned to interior wiring operations on 1 April 1944, and also assigned a range of administrative responsibilities, including dispatch and reporting duties. During his tenure with CBMU 530, his unit was commanded by an officers’ corps of six men and composed of between two hundred and twenty-eight and two hundred and eighty-four enlisted men.

But all was not well back home. Letters from his mother and siblings began to reveal troubling details about the health of his father, John Hartranft Snyder, who had been diagnosed with stomach cancer.

Emergency Leave

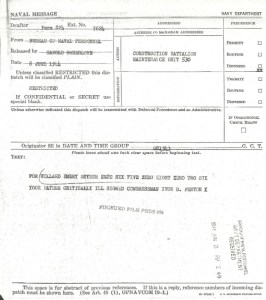

U.S. Congressman Ivor Fenton’s June 1944 telegram to Electrician’s Mate Willard E. Snyder at MCAS Ewa, Hawaii regarding his father’s terminal illness (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain; click to enlarge).

As spring turned to summer, letters from family and friends carried the news that Willard’s father would need to undergo major surgery at the Geisinger Hospital in Danville, Pennsylvania. That surgery, which took place on 22 May 1944, did little to improve his father’s prognosis. Later that month, a representative of the American Red Cross worked with a representative from the U.S. Bureau of Naval Personnel in Arlington, Virginia to send a telegram to the commanding officer of CBMU 530, directing that Electrician’s Mate Willard Snyder be advised that his father, John H. Snyder, was “critically ill.”

When no response was received, friends of the Snyder family contacted U.S. Congressman Ivor D. Fenton for help. Congressman Fenton, who had been a captain in the U.S. Army and a practicing physician in Schuylkill County before taking his seat as a Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1939, personally contacted Vice Admiral Randall Jacobs, the chief of the U.S. Bureau of Naval Personnel, in early June of 1944 and secured his help in bringing Willard Snyder home to see his dying father.

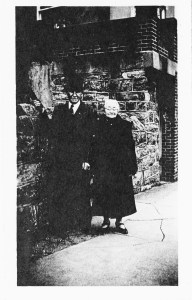

John Hartranft Snyder and Minnie R. Snyder, Snyder Family Home, Main Street, Lavelle, Pennsylvania, circa 1943. The doorway seen behind Minnie’s left shoulder was the entrance to their former dry goods store (Snyder Family Archives, used with permission; click to enlarge).

Vice Admiral Jacobs then worked with his staff and CBMU 530’s commanding officer to authorize a thirty-day emergency leave for Willard, “by first available government transportation including air,” from Midway Atoll to Pennsylvania. Departing from Midway on 8 June 1944, Willard was transported across the country to Schuylkill County, where he then made his way to his family’s home Lavelle.

While that drama was unfolding, Willard’s older sister, Lillian Snyder, was being asked by her siblings to resign from her position as a head nurse at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston “to come back home to stay with her parents,” according to “Lavelle Nurse Home,” a news report that was published in the 18 July 1944 edition of the Mount Carmel Item. (In doing so, she ultimately ended a promising career with one of the leading academic medical centers in the United States, causing her to spend the remainder of her nursing career striving to regain the power and prestige she had accrued during one of the happiest and most fulfilling periods of her life.)

Return to Duty

When his leave ended, Electrician’s Mate Willard Snyder reported for duty in San Francisco, California on 12 July 1944. Nine days later, on 21 July, he boarded the USS White Marsh L&D with hundreds of other officers and enlisted members of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps and headed out to sea. The ship’s manifest noted that they were bound for “Iron,” which, meant that they disembarked at MCAS Ewa on the island of Oahu. He was then transported to Midway, where he rejoined his unit (CBMU 530) on 28 July.

Roughly three weeks later, he received word at his duty station that his father, John Hartranft Snyder, had succumbed to cancer-related complications on 5 August 1944, and had been buried at the Citizens’ Cemetery in Lavelle. Following a brief mourning period, Willard’s sister, Kit, returned to the Boston apartment that she had previously shared with Lillian, and resumed work as a private secretary for the A. M. Byers Co., while Lillian remained behind at the Snyder family home in Lavelle to care for their grieving mother. Eenie, who was still living in Allentown, but was close enough to visit her mother regularly, returned to her job at Jewel Tea.

U.S. Navy helicopters like this one, which was photographed by Electrician’s Mate Willard E. Snyder at MCAS Ewa in Hawaii or on Midway Atoll, circa 1944, carried Seabee personnel and mail to and from the Hawaiian archipelago (Snyder Family Archives, used with permission).

Just over a month after his father’s death, Willard Snyder updated his military insurance paperwork, changing the name of his primary beneficiary from his now-deceased father to his mother, and adding his sister, Eenie, as his secondary beneficiary on 13 September. A month later, on 12 October 1944, he was reassigned to communications operations, and was transferred from the U.S. Naval Reserves’ CBMU 530 to Construction Battalion Maintenance Unit 531 (CBMU 531) on Midway Atoll in the North Pacific Ocean, for which he continued to provide communications services until he was transferred to Construction Battalion Maintenance Unit 524 (CBMU 524) on Midway on 20 November 1944. According to Walt Burgoyne, the former assistant director of education for interpretation at the National WWII Museum in New Orleans, Midway Atoll was (and remains) “the furthest western point of the Hawaiian archipelago,” and “has been a stopping point for flyers since time immemorial.”

Midway is the name of the atoll, which is comprised of three main islands, Sand, Spit and Eastern; as well as smaller ones. Atolls form, as oceanic volcanoes erupt and grow above the water line, then erode to sea level. In the case of Midway, that process began 28 million years ago, making it the second oldest of the Hawaiian chain….

In 1938, the Navy began dredging a channel between Eastern and Sand Islands, and constructed an air base on Eastern Island and sub and seaplane facilities on Sand.

* Note: Four years after that naval construction began, the United States Navy waged an epic battle against the Imperial Navy of Japan (in early June 1942) to maintain control of Midway and provide greater security for its naval bases at Ewa and Pearl Harbor. Later that same month, Willard E. Snyder enlisted in the U.S. Navy.

Still based on Midway Atoll in December 1944, but now a member of CBMU 524’s roster — a roster that would fluctuate between five hundred and fifty and six hundred officers and enlisted men moving forward — Willard E. Snyder was assigned once again to communications duties. As his time on Midway wore on, his unit would be divided into three companies — two of which would be stationed on Sand Island, with the other stationed at Eastern Island (by March of 1945).

* Note: Willard Snyder’s transfer from CBMU 531 to CBMU 524 was a direct result of the U.S. Navy’s decision to consolidate its myriad units. As a result, CBMU 531 was deactivated on 20 November 1944, and its personnel were absorbed by CBMU 524.

1945

U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt with childhood polio survivors, Warm Springs, Georgia, early 1940s (public domain).

Soldiering on in their respective military and civilian capacities, the Snyder siblings continued to grieve the loss of their patriarch. Their worries also increased when they read the shocking news that U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had died on 12 April 1945. Although they understood, intellectually, that there would be a smooth transition of power at their nation’s highest level, as Vice President Harry Truman became the next president of the United States, they worried about what might happen next as the nation’s sailors and soldiers continued their fight to bring an end to World War II under the leadership of a new commander-in-chief. Joining with others across the nation who mourned the late president, they read news coverage of his death and funeral, which included memorable images in Life Magazine and other publications that were created by renowned photographers Wayne F. Miller, Ed Clark, et. al.

Their fears gradually morphed into halting feelings of hope, however, as word spread that an end to the global conflict might be closer than they had dared dream. Buoyed by a radio broadcast on 8 May 1945, during which senior U.S. military officials proclaimed that Victory in Europe had finally been achieved, Willard Snyder’s older sisters joined with other Pennsylvanians in V-Day celebrations that were tempered, for them, by the knowledge that their beloved “baby brother” was still in harm’s way in the war’s Pacific Theater of operations.

During the summer of 1945, the Snyder sisters were finally able to relax as radio stations and newspapers announced, in mid-August, that the Empire of Japan had surrendered and, on 2 September, had formally signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender, sparking V-J (Victory over Japan) celebrations across Pennsylvania and worldwide.

They would soon see Willard again.

That reunification process began that fall when, after spending more than a year on Midway Atoll (now an insular area of the United States), Electrician’s Mate Willard E. Snyder was transferred to San Francisco, California. Departing on 18 October 1945, he arrived in San Francisco on 26 October, and was subsequently transferred to the U.S. Naval Air Station in Olathe, Kansas, where he became so ill that he was redirected by a superior officer to the U.S. Naval Hospital in Great Lakes, Illinois. Admitted there on 9 November, he was given roughly two weeks of treatment for malaria, which he had contracted while in service to the nation. Transferred to the U.S. Navy Processing Center in Bainbridge, Maryland on 20 November 1945, he finally received his honorable discharge from the U.S. Navy on 24 November 1945.

He then returned home to Schuylkill County, where he began a nearly thirty-year career with the Bell Telephone Company of Pennsylvania.

A Civilian — But Still a Public Servant

Post-war, Willard Snyder quickly began to rebuild his life. After moving back into the Snyder family home on Main Street in Lavelle, where his sister, Lillian, was still providing nursing care to their aging mother, he secured his old job with Bell Telephone, ensuring that government, business and residential customers had reliable telephone service — especially in dangerous weather conditions. Their older sister, Eenie, continued to live and work in Allentown.

Still residing in Massachusetts two years later, their younger sister, Kit, married steel industry salesman Charles Francis Courtney, Jr. in Boston on 12 July 1947, enjoyed a brief honeymoon, and then began to make a new life with him in the city of Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

1950s

The abandoned Lavelle School, at left, and the former Snyder family home, at right, on Main Street in Lavelle, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, circa 1980s (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

In April of 1950, a federal census enumerator confirmed that Willard Snyder was employed as a repairman for the Bell Telephone Company of Pennsylvania and was residing in the Snyder siblings’ childhood home on Main Street in Lavelle as the head of a household that included his wife, Genevieve (Krupa) Snyder (1918-1997), and their daughter, Judy Leah Snyder (1947-2023). Also living with them were Willard’s mother, Minnie, and his still-unmarried sister, Lillian E. Snyder, who was now employed as a registered nurse at a nearby hospital.

* Note: Sometime after April 1950, Lillian Snyder opted to join the clinical nursing faculty at the Allentown General Hospital in Lehigh County. At that time, the still-single Lillian moved into an apartment in Allentown with her older sister, Eenie, who was also still single and still working for Jewel Tea as a bookkeeper. From that point forward, they would continue to live together for the remainder of Eenie’s life (first in Allentown, then in Baltimore, Maryland, and finally in Lancaster, Pennsylvania).

Still residing in Lancaster with her husband, Charles Courtney, at the dawn of the 1950s, their sister, Catharine (Snyder) Courtney, lived with him in an apartment building at 912 New Holland Avenue. Their happy times were cut short, however, when Charlie died, leaving Kit as a grief-stricken, forty-four-year-old widow. Felled by an acute coronary occlusion on 1 December, “Cholly” (as Kit called him) had passed away at the Lancaster General Hospital at 1:01 a.m. on 2 December. Subsequently cremated, his remains were later inurned in the columbarium at the Charles Evans Cemetery in Reading.

Around the same time that Willard Snyder’s mother moved to Allentown — to allow for her daughters to give her daily, professional nursing care while she battled cancer, Willard Snyder moved his wife and daughter, Judy, into the first true home of their own — at 154 Centre Street in the Borough of Frackville, Schuylkill County. During the fall of 1951, Willard and Genevieve Snyder welcomed the birth of their second daughter, Madge Beverly Snyder, who was subsequently christened at Frackville’s Trinity Evangelical Congregational Church during a ceremony that was officiated by the Reverend Kenneth R. Maurer.

Graves of Willard Emery Snyder’s parents, John Hartranft Snyder and Minnie R. (Strohecker) Snyder, and Willard’s older brother, Tim, Citizens’ Cemetery, Lavelle, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania (Snyder Family Archives, used with permission).

But, Willard Snyder’s mother, would not have long to watch her granddaughters grow. After a long and challenging life, Minnie R. (Strohecker) Snyder died in Allentown at the age of eighty, on 28 April 1952, and was laid to rest beside her husband at the Citizens’ Cemetery in Lavelle, Schuylkill County.

Then, during the summer of 1953, Willard and Genevieve Snyder welcomed the birth of their third daughter, Christine Lenore Snyder, at the Ashland Hospital in Ashland. A month later, Willard Snyder’s fifty-three-year-old sister, Nona, wed Allen Adam Albert (1907-1993), the owner of Albert’s clothing store in Pine Grove, Schuylkill County. Their wedding ceremony was held at the First Evangelical Congregational Church in Lebanon, Pennsylvania at 8 a.m., on 23 September 1953.

Three years later, Eenie and Lillian Snyder relocated to Baltimore, Maryland, where Lillian had accepted a position as a registered nurse with Merck Sharp & Dohme, the pharmaceutical company known for its development of streptomycin, the first medication proven to be effective in the treatment of tuberculosis — the disease which had sickened and killed their paternal grandmother, Catharine (Boyer) Snyder. During Lillian’s tenure at Merck, her employer would become increasingly renowned and profitable for its research and development of medications to treat heart disease and vaccinations that prevented the spread of measles, mumps and rubella, saving the lives of countless children worldwide.

Roughly three years after his sisters’ relocation to Baltimore, Willard Snyder was transferred to the Bell Telephone Exchange in the city of Reading, which was located at 413 Washington Street. A key corporate hub, the large building housed telephone operators and telephone technology personnel — the inside line and switching maintenance workers who kept local and long distance telephone services functioning for a region with more than half a million residents.

A forty-two-year-old father, Willard Snyder was now employed as a switchman, enabling him to further raise his family’s standard of living. So, he and his wife, Genevieve, went house hunting and ultimately found the perfect spot to raise their three school-aged daughters — a three-bedroom, split-level home in the Borough of West Lawn in Berks County with front and back yards that were large enough for playing badminton, baseball and croquet (and even better for reenacting epic “military battles” from well-built forts in the winter and summer).

They then promptly enrolled their daughters with the Wilson School District in West Lawn — a public school system that was and still is widely respected for its rigorous academic programs and diverse arts, humanities and sports electives. Later that same year (1959), Willard and Genevieve Snyder welcomed the birth of their youngest daughter, Laurie Elizabeth Snyder, at the Reading Hospital in West Reading, Berks County.

1960s — 1970s

The Zephyr train ride was a “must do” for Willard Snyder’s youngest daughter every time he took her to Dorney Park (Zephyr and Journey to the Center of the Earth attractions, Dorney Park, Allentown, Pennsylvania, public domain).

During the mid-1960s, Willard Snyder was transferred to Bell Telephone’s smaller exchange building on South Hull Street in the Borough of Sinking Spring in Berks County, where he worked with a small staff to maintain the crossbar switching system that was located there, before Bell Telephone opened its new exchange building just around the corner — on Penn Avenue in Sinking Spring. After helping the new Sinking Spring exchange to open and operate smoothly, he was then transferred to Bell Telephone’s exchange in Shillington, Berks County.

A proud dad, Willard became a fixture at band concerts, school science fairs and sporting events. He also took his wife and children on regular “Sunday drives,” that were often lengthened by enthusiastic, “Where does that road go, Daddy?” prompts by his daughters to turn this way or that, taking them through Pennsylvania’s beautiful countryside as they hunted for wayside historical markers and farm stands, where they found the sweetest ears of summer corn and the sharpest of Amish sharp cheeses. (Like their father and mother before them, all four of Willard and Genevieve Snyder’s daughters were also raised in a household filled with music, the melodies of Beethoven and Chopin mingling with the Big Band rhythms of Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller and the marches of John Philip Sousa. All four became pianists like their father, and three were active in their school district’s nationally renowned instrumental music program.)

Longer outings took the family to Dorney Park in Allentown, Dutch Wonderland in Lancaster and to Baltimore to visit Willard’s sisters, Eenie and Lillian, who also became regular fixtures at the West Lawn dinner table of Willard, Genevieve and their daughters as the 1960s wound down. When he wasn’t driving his kids to and fro, though, Willard Snyder could be found in the kitchen making his mincemeat pie for Christmas dessert — or out on his family’s backyard patio, firing up the grill during the summer in order to try out the latest recipe he’d found in Parade magazine. (His peanut butter-glazed ham became a family favorite, but his “seafood surprise” was never repeated.)

Sadly, the largely happy years of the 1960s ended on a sad note when Willard Snyder’s older brother suffered a stroke during the fall of 1969. Hospitalized for roughly a week, John Sylvester Snyder (“Uncle Johnny”) died in Allentown on 12 November and was then laid to rest at that city’s Cedar Hill Memorial Park.

Illness, Death and Interment

Graves of Willard Emery Snyder (1917-1972) and his wife, Genevieve (Krupa) Snyder (1918-1997), Sinking Spring Cemetery, Berks County, Pennsylvania (public domain).

Ailing with heart disease for a decade (a disease that may actually have had its genesis in the malaria that he contracted while serving with the U.S. Seabees in the Pacific Theater during World War II), Willard Snyder had already recovered from one heart attack in 1965 when he suffered a major coronary event on Friday, 10 November 1972. Transported from the Bell Telephone office in Shillington, where he had been working that day, to the Reading Hospital in West Reading, he was pronounced dead at the hospital later that same day. Just fifty-five years old at the time of his passing, he had been scheduled to begin vacation that weekend.

Following funeral services at the Lamm and Whitman Funeral Home in Wernersville, Berks County on a cold and rainy day, Willard Emery Snyder was laid to rest on a hillside at that county’s Sinking Spring Cemetery.

A wonderful father and a genuinely good man, he is still greatly missed by his daughters.

Sources:

- “100 Years Ago–1911” (news brief regarding the 1911 fire which destroyed the family home of Chester H. Snyder, Sr.’s parents). Pottsville, Pennsylvania: Pottsville Republican, 17 March 2011.

- Attendance, Graduation and Employment Records of Lillian Estelle Snyder, Reading Hospital School of Nursing, 1927-1939 (Willard E. Snyder’s older sister). West Reading, Pennsylvania: Office of the Registrar, School of Nursing, Reading Hospital.

- “Baptism” (christening announcement of Willard E. Snyder’s second daughter), in “Frackville News.” Mahanoy City, Pennsylvania: The Record-American, 11 December 1951.

- Beyerle, Emma; and Snyder, H. Corinne [sic, Corrine], Catharine R. and Lillian E., in U.S. Census (City of Reading, Fourteenth Ward, City of Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1930). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Burgoyne, Walt. “Midway Before and After.” New Orleans, Louisiana: The National WWII Museum, 30 May 2020.

- Catharine Snyder (paternal grandmother of Willard E. Snyder), in Death Certificates (file no.: 91429, registered no.: 1242, date of death: 8 August 1918). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- Charles F. Courtney (brother-in-law of Willard E. Snyder), in Death Certificates (file no.: 103378, registered no.: 912, date of death: 2 December 1950). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- Courtney, Charles F. and Catharine R., in Polk’s Lancaster City Directory, 1950. Boston, Massachusetts: R. L. Polk & Co., Inc., Publishers, 1950.

- Courtney, Charles F. and Catharine R., in Polk’s Lancaster City Directory, 1960. Boston, Massachusetts: R. L. Polk & Co., Inc., Publishers, 1960.

- “Daughter Born” (birth of Willard E. Snyder’s third daughter), in “Frackville News.” Shenandoah, Pennsylvania: Evening Herald, 3 August 1953.

- “Ewa Plain Battlefield,” in “Historic Places.” Honolulu, Hawaii: Historic Hawai’i Foundation, retrieved online 29 July 1931.

- “Former Naval Construction Battalion Davisville,” in BRAC Bases: Northeast.” San Diego, California: U.S. NAVFAC (Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command), retrieved online 29 July 2025.

- Godcharles, Frederic. Biological and Genealogical Sketches from Central Pennsylvania, vol. 4, p. 257: “John S. Snyder” (regarding the life of Willard E. Snyder’s older brother). New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, Inc., 1944.

- “Great Depression Facts.” Hyde Park, New York: FDR Library & Museum, retrieved online 16 February 2025.

- “J. S. Snyder, 65 Once of Sunbury” (obituary of Willard E. Snyder’s older brother, John Sylvester Snyder). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Daily Item, 13 November 1969.

- John H. Snyder (father of Willard E. Snyder), in Death Certificates (file no.: 73704, registered no.: 184, date of death: 5 August 1944). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- “John H. Snyder” (father of Willard E. Snyder), in “Deaths.” Pottsville, Pennsylvania: Pottsville Republican, 7 August 1944.

- “John H. Snyder, Lavelle, Phone Official, Dies” (obituary of Willard E. Snyder’s father). Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania: Mount Carmel Item, 7 August 1944.

- “John H. Snyder, Lavelle Businessman, Dies at 70” (obituary of Willard E. Snyder’s father). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Daily Item, 8 August 1944.

- John S. Snyder (older brother of Willard E. Snyder), in Death Certificates (no.: 109888, date of death: 12 November 1969). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- John Sylvester Snyder (older brother of Willard E. Snyder), in Applications for Membership, 1946. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania Society of the National Society Sons of the American Revolution.

- Kauffman, Dana. “Malaria May Impact the Heart More Than Previously Thought.” Washington, D.C.: American College of Cardiology, 2022.

- “Lavelle Nurse Home” (article about the resignation of Willard E. Snyder’s older sister, Lillian E. Snyder, from her position as a head nurse at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts to return home to Lavelle, Pennsylvania to care for their dying father). Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania: Mount Carmel Item, 18 July 1944.

- “Lavelle Seabee Home from Africa on 30-Day Furlough” (report on the return home of Willard E. Snyder to visit his dying father). Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania: Mount Carmel Item, 12 July 1943.

- Maurer, Russ. “Lavelle Telegraph Telephone Company Chartered in 1908” (article presenting the history of the Snyder family’s involvement in the telephone industry with photo of the Snyder family home in Lavelle, Pennsylvania, where Willard E. Snyder was raised), in “Memories of Russ Maurer.” Hegins, Pennsylvania: The Citizen-Standard, circa 1990s.

- “Miss Nona Snyder Is Married Today to Pine Grove Man” (article describing the wedding ceremony of Willard E. Snyder’s oldest sister, Nona M. Snyder, to clothing store owner Allen A. Albert). Lebanon, Pennsylvania: Lebanon Daily News, 23 September 1953.

- “Mrs. John H. Snyder” (obituary of Willard E. Snyder’s mother). Pottsville, Pennsylvania: Pottsville Republican, 29 April 1952.

- “Mrs. Minnie Snyder” (obituary of Willard E. Snyder’s mother), in “Recent Deaths.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 30 April 1952.

- “Naval Construction Maintenance Unit 524.” Washington Navy Yard, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, retrieved online 29 July 2025.

- “Naval Construction Maintenance Unit 530.” Washington Navy Yard, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, retrieved online 29 July 2025.

- “Naval Construction Maintenance Unit 531.” Washington Navy Yard, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, retrieved online 29 July 2025.

- “No. 5 Crossbar Tour” (video of a working crossbar switching system similar to the one maintained by Willard E. Snyder for the Bell Telephone Company of Pennsylvania’s Sinking Spring Exchange during the late 1960s). Seattle, Washington: Connections Museum, 2016.

- Nona, Corrine and “Kitty” Snyder (newspaper mention of Willard E. Snyder’s older sisters), in “Personal Mention.” Reading, Pennsylvania: The Reading Eagle, 26 August 1926.

- Norris, L. David, James C. Milligan and Odie B. Faulk. William H. Emory: Soldier-Scientist. Tucson, Arizona: The University of Arizona Press, 1998.

- Resnick, Ben. “Resurrection of a Lost Battlefield: Ewa Plain.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Park Service, June 2019.

- Snyder, Catharine R. and Courtney, Charles F., in “Massachusetts Vital Records Index to Marriages” (documentation of the marriage of Willard E. Snyder’s older sister, Catharine, in Boston in 1947). Boston, Massachusetts: New England Historic Genealogical Society.

- Snyder, Catharine R. and Lillian, E., in The Boston Directory for the Year Commencing July 1, 1942 (Boston, Massachusetts, 1942). Chicago, Illinois: R. L. Polk Publishers, 1942.

- Snyder, Chester (Willard E. Snyder’s older brother), May and Corinne, in U.S. Census (Borough of Ashland, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, 1940). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Snyder, Chester H. (Willard E. Snyder’s older brother), May R., Corinne M., Susan K., Chester H. Jr., and Barbara H., in U.S. Census (Mount Carmel, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, 1950). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Snyder, Corrine and Catharine (address listings for Willard E. Snyder’s older sisters), in Reading City Directory, 1926. Reading, Pennsylvania: Boyd’s City Directories.

- Snyder, Corrine, Lillian E. and Catharine R. (Willard E. Snyder’s older sisters), in U.S. Census (City of Reading, Fourteenth Ward, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1940). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Snyder, H. Corrine (Willard E. Snyder’s older sister), in U.S. Census (Allentown, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, 1950). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Snyder, John H. (Willard E. Snyder’s father), Minnie R., Timothy P. and Nona M., in U.S. Census (Butler Township, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, 1900). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Snyder, John H. (Willard E. Snyder’s father), Minnie R., Timothy P., Nona M., H. Corrine, John S., Catharine R., and Lillian E., in U.S. Census (Lavelle, Northwest Butler Township, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, 1910). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Snyder, John H., Minnie R., Nona, Corrine, John S., Catharine R., Lillian E., Chester H., and Willard E. in U.S. Census (Butler Township, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, 1920). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Snyder, John H., Minnie, Nona M., John S., and Willard E. in U.S. Census (Butler Township, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, 1930). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Snyder, John S. (Willard E. Snyder’s older brother), Catherine R., John A., and David C., in U.S. Census (Sunbury, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, 1950). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Snyder, Willard E., in “Applications for World War II Compensation — To Be Used by Honorably Discharged Veteran or Person Still in Service” (18 January 1950). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, World War II Veterans’ Compensation Bureau.

- Snyder, Willard E., et. al., in “Report of Changes of U.S.S. White Marsh L&D” (date of sailing from San Francisco to IRON: U.S. Navy, 21 July 1944). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Snyder, Willard E., et. al., in “Report of Changes of U.S.S. Prairie” (date of sailing from San Francisco: U.S. Navy, 15 November 1943. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Snyder, Willard E., Genevieve Krupa, and Judy Leah, in Texas Birth Index (Houston, Harris County, Texas, 23 February 1947). Austin, Texas: Texas Department of State Health Services.

- Snyder, Willard E. (head of household), Jene M. [sic, Genevieve; wife of Willard], Judy L. (daughter of Willard), Minnie R. (Willard’s mother), and Lillian E., in U.S. Census (Lavelle, Butler Township, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, 1950). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Snyder, Willard E., in “Records of Burial Places of Veterans” (Sinking Spring Cemetery, Spring Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1972). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Military Affairs.

- “Stock Market Crash of 1929,” in “The Great Depression,” in “Federal Reserve History.” Washington, D.C.: Federal Reserve, retrieved online 16 February 2025.

- “Two New Telephone Companies” (mention of the telephone company co-founded by Willard E. Snyder’s father). Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: The Wilkes-Barre Record, 10 October 1908. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Willard E. Snyder, in Beneficiary Identification Records Locator Subsystem (BIRLS) Death Files, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (10 November 1972). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Willard E. Snyder, in Death Certificates (local reg. no.: 1921, primary dist. no.: 06812-085, date of death: 10 November 1972). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- Willard E. Snyder, in U.S. Social Security Death Index (November 1972). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Willard E. Snyder in San Francisco.” Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania: Mount Carmel Item, 2 November 1945.

- Willard E. Snyder, Genevieve K. Snyder, and Laurie E. Snyder, in “Application for Junior Life Insurance” (24 November 1959). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Penn Mutual Life Insurance Company.

- Willard Emery Snyder, in Birth Certificates (file no.: 150561, registered no.: 183, date of birth: 31 July 1917). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- Willard Emery Snyder, in U.S. Draft Registration Cards (Local Board No. 5, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, 16 October 1940).

You must be logged in to post a comment.