Alternate Spellings of Surname: Sloan, Sloane

Corporal David L. Sloan in his Grand Army of the Republic Uniform, circa 1890s (used with permission, courtesy of David L. Sloan).

Described as “one of Elkton’s best-known citizens” in his later years, David Livingston Sloan was a native Pennsylvanian who helped to preserve America’s Union during the American Civil War and then helped the nation to not only recover from that disastrous war, but to grow and prosper during the eras of Reconstruction and the Gilded Age.

He was also a fireman who protected the communities where he lived—and the nation that he loved.

Formative Years

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on 4 August 1835, David Livingston Sloan was a son of William and Sarah Stone. He was baptized on 25 October of that same year by the Rev. Thomas Neale at that city’s West York Street Methodist Episcopal Church.

As he grew to manhood and experienced more of life in Philadelphia and its surrounding communities, he began to hone his interests in community fire protection during his late teens and early twenties, and ultimately chose to become a member of one of Philadelphia’s first volunteer fire companies.

Civil War

The U.S. Capitol Building, unfinished at the time of President Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration, was still not completed when the 127th Pennsylvania Volunteers arrived in Washington, D.C. in September 1861 (public domain).

A resident of Harrisburg in 1862, David Sloan initially enlisted for service in the American Civil War as a twenty-seven-year-old stone cutter. Enrolled at Camp Curtin on 31 July 1862, he mustered in that same day as a private with Company F of the 127th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, which was frequently positioned on the far-right side of the regiment during its engagements with the enemy. He was promoted to the rank of sergeant in August 1862.

His Civil War journey truly began when he and his fellow 127th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Curtin at 9:30 a.m. on 17 August 1862, marched to Harrisburg’s railroad station, hopped aboard a Northern Central Railway train, and headed to York and then Baltimore, where they disembarked around 5 p.m. Marched to a soldiers’ rest station, they had the opportunity to eat, stretch their legs and rest there before being marched back to the railroad station, where they boarded a Baltimore and Ohio train and headed for Washington, D.C. at 10 p.m. Disembarking after their arrival in the nation’s capital shortly after 1:30 a.m. on 18 August, they were marched to the soldiers’ rest area in that city, where they slept, ate breakfast, and then reassembled on orders to march for Virginia at 11 a.m.

Their first dress parade was held at Camp Welles in Virginia on Tuesday evening, 19 August. Stationed there until 23 August 1862, they marched for another Union encampment near Fort Ethan Allen. In short order, the members of the regiment’s B Company were assigned to guard the Chain Bridge. From that time until 1 December, the regiment was stationed at several different camps, and was assigned to protect the chain bridge or was posted to picket details. Their final home during this phase of duty was Camp Dauphin.

Marching forth from that camp on a rainy 1 December, they marched back to Washington, D.C., then to the Navy Yard and then on into Maryland, where they were ordered to create a new encampment near an asylum. Trekking toward Piscataway the next morning, they made camp again. Moving on the next morning, they marched and made camp—this time near Port Tobacco, now as part of a large brigade. On 4 December, they marched until ordered to make camp yet again.

The next morning (5 December 1862), a cold, rainy and snowy day, they marched an additional seven miles, arriving at Liverpool Point and the Potomac River, where they boarded a steamship and were transported to Acquia Creek Landing. Remaining there until 8 December, they marched an additional eight miles before re-pitching their tents. Assigned to the U.S. Army of the Potomac’s 3rd Brigade, Second Division, Second Corps on 9 December, the 127th Pennsylvanians were positioned at the right of their brigade, atop a hill, from which they were afforded views of Falmouth, Virginia and Fredericksburg, Maryland. Their encampment at this juncture was known as Camp Alleman.

Armed with ninety rounds of ammunition and six days’ worth of food on 11 December, they marched to the Lacey House, across a pontoon bridge and on into action near Fredericksburg, Maryland, where they fought hard, but were forced to fall back during the Battle of Fredericksburg. By 16 December, they were back at Camp Alleman, before moving on to Camp Rohrer and then Camp J. Wesley Awl.

Subsequently assigned to occupation duties near Falmouth through the end of March 1863, they took part in the Chancellorsville Campaign from 27 April through 6 May, during which time were involved in the Operations at Franklin’s Crossing (29 April to 2 May) and in Union actions near Marye’s Heights (3 May), Salem Heights (3-4 May) and Bank’s Ford (4 May). Ultimately sent back to Pennsylvania, they were officially mustered out as a regiment on 29 May 1863.

Afterward, Private David Sloan arrived at his home in the Philadelphia area, and subsequently wed Johanna Michael (1835-1901), a native Pennsylvanian who had been born on 15 November 1835, and was a sister of his friend, William M. Michael. Their wedding likely took place between June and December 1863 because their first son was born just over eight months after the start of the New Year.

1864

With the American Civil War still showing no signs of cooling by New Year’s Day, 1864, David Sloan made the decision to re-enlist and continue the fight to preserve America’s Union. Standing right beside him when he re-enrolled as a Veteran Volunteer in Philadelphia on 23 January of that year, was his friend and brother-in-law William M. Michael. Both men were officially mustered in at Philadelphia as privates with Company C of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Military records at the time described Private David Sloan as a twenty-nine-year-old native of Philadelphia, who was employed as a stone cutter, and who was five feet, seven-and-three-quarter inches tall with dark hair, brown eyes and a dark complexion. Although he likely did not know it at the time, he was leaving behind a pregnant wife to join a battle-hardened regiment that was about to make history as the only regiment from Pennsylvania to take part in the Union’s 1864 Red River Campaign across Louisiana.

Regimental muster rolls of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry appear to indicate, however, that neither Private David Sloan, nor his brother-in-law, Private William Michael, were participants in the major battles of that campaign. Bearing the notations, “Joined from recruiting depot as Vet. Vol. (as per Genl Orders No. 191-216), June 5, 1864,” for Private Sloan, and “Joined from recruiting depot Sep. 18, 1864,” for Private Michael, the muster rolls show that both men were likely transported separately— to different duty stations for the 47th Pennsylvania at different times—with Private Sloan likely transported from Pennsylvania by ship to Morganza, Louisiana, where the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were encamped with other regiments from the U.S. Army of the Gulf for most of June 1864. (Private Michael apparently did not connect with the 47th Pennsylvania until roughly three months later, when it was stationed in Virginia as part of Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign.)

What is known for certain is that, on 7 July 1864, Private David Sloan and his fellow C Company comraded boarded the U.S. Steamer McClellan and sailed out of the harbor at New Orleans with the members of Companies A, D, E, F, H, and I, under orders to return to the East Coast. (The men from Companies B, G and K would depart later that month and reconnect with the regiment at Monocacy.)

An Encounter with Lincoln and Snicker’s Gap

Following their arrival in Virginia and a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln on 12 July, the advance group of 47th Pennsylvanians joined up with Major-General David Hunter’s forces in mid-July 1864, at Snicker’s Gap, Virginia, where they fought in the Battle of Cool Spring and subsequently assisted in defending Washington, D.C. while also helping to drive Confederate troops from Maryland.

On 24 July 1864, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin was promoted from leadership of Company C to the 47th Pennsylvania’s central regimental command staff and was also awarded the rank of major. First Lieutenant Daniel Oyster was soon tapped to fill Gobin’s shoes—a promotion that was made official when he was commissioned as captain of C Company on 1 September 1864.

That same day, William Hendricks was promoted from second to first lieutenant, Sergeant Christian S. Beard was promoted to second lieutenant, Sergeant William Fry was promoted to the rank of first sergeant, Private John Bartlow was promoted to the rank of sergeant, and Private Timothy M. Snyder was promoted to the rank of corporal.

By that point, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had become part of the Middle Military Division of the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah and were serving under Major-General Philip H. Sheridan.

It was also during this time that Private David Sloan received word from home that his wife, Johanna (Michael) Sloan, had given birth to their first child—Joseph Hooker Sloan (1864-1947)—who was born in Pennsylvania on 16 August 1864 and had been named after famed Union Army General Joseph Hooker.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Berryville Pike, Virginia, as viewed from the west, with the Blue Ridge Mountains in the distance on the horizon (T. D. Biscoe DeGloyer, 1 August 1884, courtesy of Southern Methodist University).

From 3-4 September, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers fought in the Battle of Berryville, Virginia and engaged in related post-battle skirmishes with the enemy over subsequent days. On one of those days (5 September 1864), Captain Oyster and Private David Sloan, were wounded at Berryville. Both received medical treatment and returned to duty with the regiment.

Roughly two weeks later, Color-Bearer Benjamin Walls, the oldest member of the entire regiment, was mustered out upon expiration of his three-year term of service on 18 September—despite his request that he continued to be allowed to continue his service to the nation. C Company Privates D. W. and Isaac Kemble, David S. Beidler, R. W. Druckemiller, Charles Harp, John H. Heim, former prisoner of war Conrad Holman, George Miller, William Pfeil, William Plant, and Alex Ruffaner also mustered out the same day upon expiration of their respective terms of service.

Valor and Persistence

Battle of Opequan (aka Third Winchester), Virginia, 19 September 1864 (public domain; click to enlarge).

Inflicting heavy casualties during the Battle of Opequan (also known as “Third Winchester”) on 19 September 1864, Sheridan’s gallant blue jackets forced a stunning retreat of Jubal Early’s grays—first to Fisher’s Hill (21-22 September) and then, following a successful early morning flanking attack, to Waynesboro. These impressive Union victories helped Abraham Lincoln secure his second term as president. Recalling the battle years later, Sheridan noted:

My army moved at 3 o’clock that morning. The plan was for Torbert to advance with Merritt’s division of cavalry from Summit Point, carry the crossings of the Opequon at Stevens’s and Lock’s fords, and form a junction near Stephenson’s depot, with Averell, who was to move south from Darksville by the Valley pike. Meanwhile, Wilson was to strike up the Berryville pike, carry the Berryville crossing of the Opequon, charge through the gorge or cañon on the road west of the stream, and occupy the open ground at the head of this defile. Wilson’s attack was to be supported by the Sixth and Nineteenth corps, which were ordered to the Berryville crossing, and as the cavalry gained the open ground beyond the open gorge, the two infantry corps, under command of General Wright, were expected to press on after and occupy Wilson’s ground, who was then to shift to the south bank of Abraham’s creek and cover my left; Crook’s two divisions, having to march from Summit Point, were to follow the Sixth and Nineteenth corps to the Opequon, and should they arrive before the action began, they were to be held in reserve till the proper moment came, and then, as a turning-column, be thrown over toward the Valley pike, south of Winchester.”

By dawn on 19 September, the brigade from Wilson’s division, headed by McIntosh, had succeeded in compelling Confederate pickets to flee their Berryville positions with “Wilson following rapidly through the gorge with the rest of the division, debouched from its western extremity with such suddenness as to capture a small earthwork in front of General Ramseur’s main line.” Although “the Confederate infantry, on recovering from its astonishment, tried hard to dislodge them,” they were unable to do so, according to Sheridan. Wilson’s Union troops were then reinforced by the U.S. 6th Army.

I followed Wilson to select the ground on which to form the infantry. The Sixth Corps began to arrive about 8 o’clock, and taking up the line Wilson had been holding, just beyond the head of the narrow ravine, the cavalry was transferred to the south side of Abraham’s Creek.

The Confederate line lay along some elevated ground about two miles east of Winchester, and extended from Abraham’s Creek north across the Berryville pike, the left being hidden in the heavy timber on Red Bud Run. Between this line and mine, especially on my right, clumps of woods and patches of underbrush occurred here and there, but the undulating ground consisted mainly of open fields, many of which were covered with standing corn that had already ripened.

“The 6th Corps formed across the Berryville Road” while the “19th Corps prolonged the line to the Red Bud on the right with the troops of the Second Division.” According to military historian Richard Irwin, the:

First Division’s First and Second Brigades, under Beal and McMillan, formed in the rear of the Second Division and on the right flank. Beal’s First Brigade was on the right of the division’s position, and McMillan’s Second Brigade deployed on the left and rear of Beal; in order of the 47th Pennsylvania, 8th Vermont, 160th New York, and 12th Connecticut, with five companies of the 47th Pennsylvania deployed to cover the whole right flank of his brigade and to move forward with it by the flank left in front. By this time, the Army of West Virginia had crossed the ford and was massed on the left of the west bank.

While the ground in front of the 6th Corps was for the most part open, the 19th Corps found itself in a dense wood, restricting its vision of both the enemy and its own forces.

“Much time was lost in getting all of the Sixth and Nineteenth corps through the narrow defile,” Sheridan observed, adding that, because Grover’s division was “greatly delayed there by a train of ammunition wagons … it was not until late in the forenoon that the troops intended for the attack could be got into line ready to advance.” As a result:

General Early was not slow to avail himself of the advantages thus offered him, and my chances of striking him in detail were growing less every moment, for Gordon and Rodes were hurrying their divisions from Stephenson’s depot across-country on a line that would place Gordon in the woods south of Red Bud Run, and bring Rodes into the interval between Gordon and Ramseur.

When the two corps had all got through the cañon they were formed with Getty’s division of the Sixth to the left of the Berryville pike, Rickett’s division to the right of the pike, and Russell’s division in reserve in rear of the other two. Grover’s division of the Nineteenth Corps came next on the right of Rickett’s, with Dwight to its rear in reserve, while Crook was to begin massing near the Opequon crossing about the time Wright and Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers] were ready to attack.

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union Army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces, Battle of Opequan, 19 September 1864 (Kurz & Allison, circa 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

More than a quarter of a century after the clash, Irwin conjured the spirit of the battle’s beginning:

About a quarter before twelve o’clock, at the sound of Sheridan’s bugle, repeated from corps, division, and brigade headquarters, the whole line moved forward with great spirit, and instantly became engaged. Wilson pushed back Lomax, Wright drove in Ramseur, while Emory, advancing his infantry [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers] rapidly through the wood, where he was unable to use his artillery, attacked Gordon with great vigor. Birge, charging with bayonets fixed, fell upon the brigade of Evans, forming the extreme left of Gordon, and without a halt drove it in confusion through the wood and across the open ground beyond to the support of Braxton’s artillery, posted by Gordon to secure his flank on the Red Bud road. In this brilliant charge, led by Birge in person, his lines naturally became disordered….

Sharpe, advancing simultaneously on Birge’s left, tried in vain to keep the alignment with Ricketts and with Birge…. At first the order of battle formed a right angle with the road, but the bend once reached, in the effort to keep closed upon it, at every step Ricketts was taking ground more and more to the left, while the point of direction for Birge, and equally for Sharpe, was the enemy in their front, standing almost in the exact prolongation of the defile, from which line, still plainly marked by Ash Hollow, the road … was steadily diverging.

As the battle continued to unfold, the disorganization affected the lines on both sides of the conflict. According to Irwin:

The 19th Corps Second Division was initially successful, but in its charge became disorganized; and the troops on the left in following the less obstructed area of the road which veared [sic] slightly left, soon opened up a gap on their right; while the remainder of the Union forces were moving straight ahead as they engaged the Confederates. This gap eventually reached 400 yards in width, an opportunity the Confederates soon exploited. Fortunately the Confederates were soon themselves disorganized by their advance, and encountering fresh Union troops on their right flank were halted. The Confederate attack on the right flank also achieved initial success, until halted by Beal’s first brigade.

McMillan had been ordered to move forward at the same time as Beal, and to form on his left. The five companies of the 47th Pennsylvania that had been detached to form a skirmish line on the Red Bud Run to cover McMillan’s right flank, had some how [sic] lost their way on the broken ground among the thickets, and, not finding them in place, McMillan had been obliged to send the remaining companies of the same regiment to do the same duty, and brought the rest of the brigade to the front to restore the line. The line then charged and drove the Confederates back beyond the positions where their attack had started. The initial engagement had lasted barely an hour, and by 1 PM was over. The right flank of the 19th Corps was held by the 47th Pennsylvania and 30th Massachusetts.

According to Sheridan:

Just before noon the line of Getty, Ricketts, and Grover moved forward, and as we advanced, the Confederates, covered by some heavy woods on their right, slight underbrush and corn-fields along their centre [sic], and a large body of timber on their left along the Red Bud, opened fire from their whole front. We gained considerable ground at first, especially on our left but the desperate resistance which the right met with demonstrated that the time we had unavoidably lost in the morning had been of incalculable value to Early, for it was evident that he had been enabled already to so far concentrate his troops as to have the different divisions of his army in a connected line of battle in good shape to resist.

Getty and Ricketts made some progress toward Winchester in connection with Wilson’s cavalry…. Grover in a few minutes broke up Evans’s brigade of Gordon’s division, but his pursuit of Evans destroyed the continuity of my general line, and increased an interval that had already been made by the deflection of Ricketts to the left, in obedience to instructions that had been given him to guide his division on the Berryville pike. As the line pressed forward, Ricketts observed this widening interval and endeavored to fill it with the small brigade of Colonel Keifer, but at this juncture both Gordon and Rodes struck the weak spot where the right of the Sixth Corps and the left of the Nineteenth should have been in conjunction, and succeeded in checking my advance by driving back a part of Ricketts’s division, and the most of Grover’s. As these troops were retiring I ordered Russell’s reserve division to be put into action, and just as the flank of the enemy’s troops in pursuit of Grover was presented, Upton’s brigade, led in person by both Russell and Upton, struck it in a charge so vigorous as to drive the Confederates back … to their original ground.

The success of Russell enabled me to re-establish the right of my line some little distance in advance of the position from which it started in the early morning, and behind Russell’s division (now commanded by Upton) the broken regiments of Ricketts’s division were rallied. Dwight’s division was then brought up on the right, and Grover’s men formed behind it….

No news of Torbert’s progress came … so … I directed Crook to take post on the right of the Nineteenth Corps and, when the action was renewed, to push his command forward as a turning-column in conjunction with Emory. After some delay … Crook got his men up, and posting Colonel Thoburn’s division on the prolongation of the Nineteenth Corps, he formed Colonel Duval’s division to the right of Thoburn. Here I joined Crook, informing him that … Torbert was driving the enemy in confusion along the Martinsburg pike toward Winchester; at the same time I directed him to attack the moment all of Duval’s men were in line. Wright was introduced to advance in concert with Crook, by swinging Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania and his other 19th Corps’ troops] and the right of the Sixth Corps to the left together in a half-wheel. Then leaving Crook, I rode along the Sixth and Nineteenth corps, the open ground over which they were passing affording a rare opportunity to witness the precision with which the attack was taken up from right to left. Crook’s success began the moment he started to turn the enemy’s left…

Both Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] and Wright took up the fight as ordered…. [A]s I reached the Nineteenth Corps the enemy was contesting the ground in its front with great obstinacy; but Emory’s dogged persistence was at length rewarded with success, just as Crook’s command emerged from the morass of the Red Bud Run, and swept around Gordon, toward the right of Breckenridge….”

As “Early tried hard to stem the tide” of the multi-pronged Union assault, “Torbert’s cavalry began passing around his left flank, and as Crook, Emory, and Wright attacked in front, panic took possession of the enemy, his troops, now fugitives and stragglers, seeking escape into and through Winchester,” according to Sheridan.

When this second break occurred, the Sixth and Nineteenth corps were moved over toward the Millwood pike to help Wilson on the left, but the day was so far spent that they could render him no assistance.” The battle winding down, Sheridan headed for Winchester to begin writing his report to Grant.

According to Irwin, although the heat of battle had cooled by 1 p.m., troop movements had continued on both sides throughout the afternoon until “Crook, with a sudden … effective half-wheel to the left, fell vigorously upon Gordon, and Torbert coming on with great impetuosity … the weight was heavier than the attenuated lines of Breckinridge and Gordon Could bear.” As a result, “Early saw his whole left wing give back in disorder, and as Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] and Wright pressed hard, Rodes and Ramseur gave way, and the battle was over.”

Early vainly endeavored to reconstruct his shattered lines [near Winchester]. About five o’clock Torbert and Crook, fairly at right angles to the first line of battle, covered Winchester on the north from the rocky ledges that lie to the eastward of the town…. Thence Wright extended the line at right angles with Crook and parallel with the valley road, while Sheridan drew out Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] … and sent him to extend Wright’s line to the south….

Sheridan, mindful that his men had been on their feet since two o’clock in the morning … made no attempt to send his infantry after the flying enemy….

Sheridan … openly rejoiced, and catching the enthusiasm of their leader, his men went wild with excitement when, accompanied by his corps commanders, Wright and Emory and Crook, Sheridan rode down the front of his lines. Then went up a mighty cheer that gave new life to the wounded and consoled the last moments of the dying….

Summing up the battle for Lincoln and Grant, Sheridan reported:

My losses in the Battle of Opequon were heavy, amounting to about 4,500 killed, wounded and missing. Among the killed was General Russell, commanding a division, and the wounded included Generals Upton, McIntosh and Chapman, and Colonels Duval and Sharpe. The Confederate loss in killed, wounded, and prisoners equaled about mine. General Rodes being of the killed, while Generals Fitzhugh Lee and York were severely wounded.

We captured five pieces of artillery and nine battle flags. The restoration of the lower valley – from the Potomac to Strasburg – to the control of the Union forces caused great rejoicing in the North, and relieved the Administration from further solicitude for the safety of the Maryland and Pennsylvania borders. The President’s appreciation of the victory was expressed in a despatch [sic] so like Mr. Lincoln I give a fac-simile [sic] of it to the reader. This he supplemented by promoting me to the grade of brigadier-general in the regular army, and assigning me to the permanent command of the Middle Military Department, and following that came warm congratulations from Mr. Stanton and from Generals Grant, Sherman and Meade.

“The losses of the Army of the Shenandoah, according to the revised statements compiled in the War Department, were 5018, including 697 killed, 3983 wounded, 338 missing,” per revised estimates by Irwin. “Of the three infantry corps, the 19th, though in numbers smaller than the 6th, suffered the heaviest loss, the aggregate being 2074 [314 killed, 1554 wounded, 206 missing]. Conversely, Early “lost nearly 4000 in all, including about 200 prisoners; or as other sources reported, anywhere from 5500 to 6850 killed, wounded, and missing or captured.”

Despite the significant number of killed, wounded and missing on both sides of the conflict, casualties within the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were surprisingly low. Private Thomas Steffen of Company B was killed in action while F Company Private William H. Jackson’s cause of death was somewhat less clear; he was reported in Samuel Bates’ History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5 as having died on the same day on which the battle took place.

Among the injured were C Company Corporal Timothy Matthias Snyder, who was wounded in the knee, and Privates William Adams (E Company), Charles Pfeiffer (B Company), who lost the forefinger of his right hand, J. D. Rabenold (B Company), and Edward Smith (E Company).

As he penned his memoir in 1885 during the final days of his life, President Ulysses S. Grant again made clear the significance of the Battle of Opequan:

Sheridan moved at the time he had fixed upon. He met Early at the crossing of Opequon Creek [September 19], and won a most decisive victory – one which electrified the country. Early had invited this attack himself by his bad generalship and made the victory easy. He had sent G. T. Anderson’s division east of the Blue Ridge [to Lee] before I [Grant] went to Harpers Ferry and about the time I arrived there he started with two other divisions (leaving but two in their camps) to march to Martinsburg for the purpose of destroying the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad at that point. Early here learned that I had been with Sheridan and, supposing there was some movement on foot, started back as soon as he got the information. But his forces were separated and … he was very badly defeated. He fell back to Fisher’s Hill, Sheridan following.

On 23-24 September, the 47th Pennsylvania’s two most senior officers, Colonel Tilghman Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, mustered out upon expiration of their respective terms of service.

Battle of Cedar Creek

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, “Surprise at Cedar Creek,” captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle-pit positions, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

On 19 October 1864, Early’s Confederate forces briefly stunned the Union Army, launching a surprise attack at Cedar Creek, but Sheridan was able to rally his troops. Intense fighting raged for hours and ranged over a broad swath of Virginia farmland. Weakened by hunger wrought by the Union’s earlier destruction of crops, Early’s army gradually peeled off, one by one, to forage for food while Sheridan’s forces fought on, and won the day during the epic Battle of Cedar Creek.

According to Union General Ulysses S. Grant:

On the 18th of October Early was ready to move, and during the night succeeded in getting his troops in the rear of our left flank, which fled precipitately and in great confusion down the valley, losing eighteen pieces of artillery and a thousand or more prisoners [Battle of Cedar Creek]. The right under General Getty maintained a firm and steady front, falling back to Middletown where it took a position and made a stand. The cavalry went to the rear, seized the roads leading to Winchester and held them for the use of our troops in falling back, General Wright having ordered a retreat back to that place.

Sheridan having left Washington on the 18th, reached Winchester that night. The following morning he started to join his command. He had scarcely got out of town, when he met his men returning, in panic from the front and also heard heavy firing to the south. He immediately ordered the cavalry at Winchester to be deployed across the valley to stop the stragglers. Leaving members of his staff to take care of Winchester and the public property there, he set out with a small escort directly for the scene of the battle. As he met the fugitives he ordered them to turn back, reminding them that they were going the wrong way. His presence soon restored confidence. Finding themselves worse frightened than hurt the men did halt and turn back. Many of those who had run ten miles got back in time to redeem their reputation as gallant soldiers before night.

Not provided with adequate intelligence by his staff by that fateful morning, Sheridan began his day at a leisurely pace, clearly unaware of the potential disaster in the making:

Toward 6 o’clock the morning of the 19th, the officer on picket duty at Winchester came to my room, I being yet in bed, and reported artillery firing from the direction of Cedar Creek. I asked him if the firing was continuous or only desultory, to which he replied that it was not a sustained fire, but rather irregular and fitful. I remarked: ‘It’s all right; Grover has gone out this morning to make a reconnaissance, and he is merely feeling the enemy.’ I tried to go to sleep again, but grew so restless that I could not, and soon got up and dressed myself. A little later the picket officer came back and reported that the firing, which could be distinctly heard from his line on the heights outside of Winchester, was still going on. I asked him if it sounded like a battle, and as he again said that it did not, I still inferred that the cannonading was caused by Grover’s division banging away at the enemy simply to find out what he was up to. However, I went down-stairs and requested that breakfast be hurried up, and at the same time ordered the horses to be saddled and in readiness, for I concluded to go to the front before any further examinations were made in regard to the defensive line.

We mounted our horses between half-past 8 and 9, and as we were proceeding up the street which leads directly through Winchester, from the Logan residence, where Edwards was quartered, to the Valley pike, I noticed that there were many women at the windows and doors of the houses, who kept shaking their skirts at us and who were otherwise markedly insolent in their demeanor, but supposing this conduct to be instigated by their well-known and perhaps natural prejudices, I ascribed to it no unusual significance. On reaching the edge of town I halted a moment, and there heard quite distinctly the sound of artillery firing in an unceasing roar. Concluding from this that a battle was in progress, I now felt confident that the women along the street had received intelligence from the battlefield by the ‘grape-vine telegraph,’ and were in raptures over some good news, while I as yet was utterly ignorant of the actual situation. Moving on, I put my head down toward the pommel of my saddle and listened intently, trying to locate and interpret the sound, continuing in this position till we had crossed Mill Creek, about half a mile from Winchester. The result of my efforts in the interval was the conviction that the travel of the sound was increasing too rapidly to be accounted for by my own rate of motion, and that therefore my army must be falling back.

At Mill Creek my escort fell in behind, and we were going ahead at a regular pace, when, just as we made the crest of the rise beyond the stream, there burst upon our view the appalling spectacle of a panic-stricken army – hundreds of slightly wounded men, throngs of others unhurt but utterly demoralized, and baggage-wagons by the score, all pressing to the rear in hopeless confusion, telling only too plainly that a disaster had occurred at the front. On accosting some of the fugitives, they assured me that the army was broken up, in full retreat, and that all was lost; all this with a manner true to that peculiar indifference that takes possession of panic-stricken men. I was greatly disturbed by the sight, but at once sent word to Colonel Edwards, commanding the brigade in Winchester, to stretch his troops across the valley, near Mill Creek, and stop all fugitives, directing also that the transportation be passed through and parked on the north side of the town.

As I continued at a walk a few hundred yards farther, thinking all the time of Longstreet’s telegram to Early, ‘Be ready when I join you, and we will crush Sheridan,’ I was fixing in my mind what I should do. My first thought was to stop the army in the suburbs of Winchester as it came back, form a new line, and fight there; but as the situation was more maturely considered a better conception prevailed. I was sure the troops had confidence in me, for heretofore we had been successful; and as at other times they had seen me present at the slightest sign of trouble or distress, I felt that I ought to try now to restore their broken ranks, or, failing in that, to share their fate because of what they had done hitherto.

About this time Colonel Wood, my chief commissary, arrived from the front and gave me fuller intelligence, reporting that everything was gone, my headquarters captured, and the troops dispersed. When I heard this I took two of my aides-de-camp, Major George A. Forsyth and Captain Joseph O’Keefe, and with twenty men from the escort started for the front, at the same time directing Colonel James W. Forsyth and Colonels Alexander and Thom to remain behind and do what they could to stop the runaways.

For a short distance I traveled on the road, but soon found it so blocked with wagons and wounded men that my progress was impeded, and I was forced to take to the adjoining fields to make haste. When most of the wagons and wounded were past I returned to the road, which was thickly lined with unhurt men, who, having got far enough to the rear to be out of danger, had halted without any organization, and begun cooking coffee, but when they saw me they abandoned their coffee, threw up their hats, shouldered their muskets, and as I passed along turned to follow with enthusiasm and cheers. To acknowledge this exhibition of feeling I took off my hat, and with Forsyth and O’Keefe rode some distance in advance of my escort, while every mounted officer who saw me galloped out on either side of the pike to tell the men at a distance that I had come back. In this way the news was spread to the stragglers off the road, when they, too, turned their faces to the front and marched toward the enemy, changing in a moment from the depths of depression to the extreme of enthusiasm. I already knew that even in the ordinary condition of mind enthusiasm is a potent element with soldiers, but what I saw that day convinced me that if it can be excited from a state of despondency its power is almost irresistible. I said nothing except to remark, as I rode among those on the road: ‘If I had been with you this morning this disaster would not have happened. We must face the other way; we will go back and recover our camp.’

My first halt was made just north of Newtown, where I met a chaplain digging his heels into the sides of his jaded horse, and making for the rear with all possible speed. I drew up for an instant, and inquired of him how matters were going at the front. He replied, ‘Everything is lost; but all will be right when you get there’; yet notwithstanding this expression of confidence in me, the parson at once resumed his breathless pace to the rear. At Newtown I was obliged to make a circuit to the left, to get round the village. I could not pass through it, the streets were so crowded, but meeting on this detour Major McKinley, of Crook’s staff, he spread the news of my return through the motley throng there.

According to Grant, “When Sheridan got to the front he found Getty and Custer still holding their ground firmly between the Confederates and our retreating troops.”

Everything in the rear was now ordered up. Sheridan at once proceeded to intrench [sic] his position; and he awaited an assault from the enemy. This was made with vigor, and was directed principally against Emory’s corps [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers], which had sustained the principal loss in the first attack. By one o’clock the attack was repulsed. Early was so badly damaged that he seemed disinclined to make another attack, but went to work to intrench [sic] himself with a view to holding the position he had already gained….

Sheridan Rallying His Troops, Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

What Sheridan encountered as he approached Newtown and the Valley pike from the south made him urge Rienzi on:

I saw about three-fourths of a mile west of the pike a body of troops, which proved to be Rickett’s and Wheaton’s divisions of the Sixth Corps, and then learned that the Nineteenth Corps [to which the 47th Pennsylvania had been assigned] had halted a little to the right and rear of these; but I did not stop, desiring to get to the extreme front. Continuing on parallel with the pike, about midway between Newtown and Middletown I crossed to the west of it, and a little later came up in rear of Getty’s division of the Sixth Corps. When I arrived, this division and the cavalry were the only troops in the presence of and resisting the enemy; they were apparently acting as a rear guard at a point about three miles north of the line we held at Cedar Creek when the battle began. General Torbert was the first officer to meet me, saying as he rode up, ‘My God! I am glad you’ve come.’ Getty’s division, when I found it, was about a mile north of Middleton, posted on the reverse slope of some slightly rising ground, holding a barricade made with fence-rails, and skirmishing slightly with the enemy’s pickets. Jumping my horse over the line of rails, I rode to the crest of the elevation, and there taking off my hat, the men rose up from behind their barricade with cheers of recognition. An officer of the Vermont brigade, Colonel A. S. Tracy, rode out to the front, and joining me, informed me that General Louis A. Grant was in command there, the regular division commander General Getty, having taken charge of the Sixth Corps in place of Ricketts, wounded early in the action, while temporarily commanding the corps. I then turned back to the rear of Getty’s division, and as I came behind it, a line of regimental flags rose up out of the ground, as it seemed, to welcome me. They were mostly the colors of Crook’s troops, who had been stampeded and scattered in the surprise of the morning. The color-bearers, having withstood the panic, had formed behind the troops of Getty. The line with the colors was largely composed of officers, among whom I recognized Colonel R. B. Hayes, since president of the United States, one of the brigade commanders. At the close of this incident I crossed the little narrow valley, or depression, in rear of Getty’s line, and dismounting on the opposite crest, established that point as my headquarters. In a few minutes some of my staff joined me, and the first directions I gave were to have the Nineteenth Corps [to which the 47th Pennsylvania was attached] and the two divisions of Wright’s corps brought to the front, so they could be formed on Getty’s division prolonged to the right; for I had already decided to attack the enemy from that line as soon as I could get matters in shape to take the offensive. Crook met me at this time, and strongly favored my idea of attacking, but said, however, that most of his troops were gone. General Wright came up a little later, when I saw that he was wounded, a ball having grazed the point of his chin so as to draw the blood plentifully.

Wright gave me a hurried account of the day’s events, and when told that we would fight the enemy on the line which Getty and the cavalry were holding, and that he must go himself and send all his staff to bring up the troops, he zealously fell in with the scheme; and it was then that the Nineteenth Corps [including the 47th Pennsylvania] and two divisions of the Sixth were ordered to the front from where they had been halted to the right and rear of Getty.

After this conversation I rode to the east of the Valley pike and to the left of Getty’s division, to a point from which I could obtain a good view of the front, in the mean time [sic] sending Major Forsyth to communicate with Colonel Lowell (who occupied a position close in toward the suburbs of Middletown and directly in front of Getty’s left) to learn whether he could hold on there. Lowell replied that he could. I then ordered Custer’s division back to the right flank, and returning to the place where my headquarters had been established I met near them Rickett’s division under General Kiefer and General Frank Wheaton’s division, both marching to the front. When the men of these divisions saw me they began cheering and took up the double quick to the front, while I turned back toward Getty’s line to point out where these returning troops should be place. Having done this, I ordered General Wright to resume command of the Sixth Corps, and Getty, who was temporarily in charge of it, to take command of his own division. A little later the Nineteenth Corps [including the 47th Pennsylvania] came up and was posted between the right of the Sixth Corps and Middle Marsh Brook.

All this had consumed a great deal of time, and I concluded to visit again the point to the east of the Valley pike, from where I had first observed the enemy, to see what he was doing. Arrived there, I could plainly seem him getting ready for attack, and Major Forsyth now suggested that it would be well to ride along the line of battle before the enemy assailed us, for although the troops had learned of my return, but few of them had seen me. Following his suggestion I started in behind the men, but when a few paces had been taken I crossed to the front and, hat in hand, passed along the entire length of the infantry line; and it is from this circumstance that many of the officers and men who then received me with such heartiness have since supposed that that was my first appearance on the field. But at least two hours had elapsed since I reached the ground, for it was after mid-day when this incident of riding down the front took place, and I arrived not later, certainly, than half-past 10 o’clock.

After re-arranging the line and preparing to attack I returned again to observe the Confederates, who shortly began to advance on us. The attacking columns did not cover my entire front, and it appeared that their onset would be mainly directed against the Nineteenth Corps [including the 47th Pennsylvania], so, fearing that they might be too strong for Emory on account of his depleted condition (many of his men not having had time to get up from the rear), and Getty’s division being free from assault, I transferred a part of it from the extreme left to the support of the Nineteenth Corps. The assault was quickly repulsed by Emory, however, and as the enemy fell back Getty’s troops were returned to their original place. This repulse of the Confederates made me feel pretty safe from further offensive operations on their part, and I now decided to suspend the fighting till my thin ranks were further strengthened by the men who were continually coming up from the rear, and particularly till Crook’s troops could be assembled on the extreme left.

In consequence of the despatch [sic] already mentioned, ‘Be ready when I join you, and we will crush Sheridan,’ since learned to have been fictitious, I had been supposing all day that Longstreet’s troops were present, but as no definite intelligence on this point had been gathered, I concluded, in the lull that now occurred, to ascertain something positive regarding Longstreet; and Merritt having been transferred to our left in the morning, I directed him to attack an exposed battery then at the edge of Middletown, and capture some prisoners. Merritt soon did this work effectually, concealing his intention till his troops got close in to the enemy, and then by a quick dash gobbling up a number of Confederates. When the prisoners were brought in, I learned from them that the only troops of Longstreet’s in the fight were of Kershaw’s division, which had rejoined Early at Brown’s Gap in the latter part of September, and that the rest of Longstreet’s corps was not on the field. The receipt of this information entirely cleared the way for me to take the offensive, but on the heels of it came information that Longstreet was marching by the Front Royal pike to strike my rear at Winchester, driving Powell’s cavalry in as he advanced. This renewed my uneasiness, and caused me to delay the general attack till after assurances came from Powell, denying utterly the reports as to Longstreet, and confirming the statements of the prisoners.

Launching another advance sometime mid-afternoon during which Sheridan “sent his cavalry by both flanks, and they penetrated to the enemy’s rear,” Grant added:

The contest was close for a time, but at length the left of the enemy broke, and disintegration along the whole line soon followed. Early tried to rally his men, but they were followed so closely that they had to give way very quickly every time they attempted to make a stand. Our cavalry, having pushed on and got in the rear of the Confederates, captured twenty-four pieces of artillery, besides retaking what had been lost in the morning. This victory pretty much closed the campaign in the Valley of Virginia. All the Confederate troops were sent back to Richmond with the exception of one division of infantry and a little cavalry. Wright’s corps was ordered back to the Army of the Potomac, and two other divisions were withdrawn from the valley. Early had lost more men in killed, wounded and captured in the valley than Sheridan had commanded from first to last.

The High Price of Valor

Headstone of Sergeant William Pyers, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Company C, Winchester National Cemetery, Virginia; he was killed in the fighting at the Cooley Farm during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (courtesy of Randy Fletcher, 2014).

But it was another extremely costly engagement for Pennsylvania’s native sons. The 47th experienced a total of one hundred and seventy-six casualties during the Battle of Cedar Creek alone, including Sergeants John Bartlow and William Pyers, and Privates James Brown (a carpenter), Jasper B. Gardner (a railroad conductor), George W. Keiser (an eighteen-year-old farmer), Joseph Smith, John E. Will, and Theodore Kiehl—all dead.

Most of those deceased heroes were simply described in the U.S. Army’s death ledger for 1864 as “killed in action.” Many were initially buried near where they fell and then later exhumed and reinterred at the Winchester National Cemetery in Winchester, Virginia, during the federal government’s large-scale effort to properly bury Union Army soldiers at national cemeteries.

Among those who had been wounded, but survived, was Private David Sloan’s friend and brother-in-law, Private William Michael. Provided stabilizing medical care in the field, he was later transported back to Pennsylvania, where he received more advanced care.

In recounting the events of that terrible day in a letter later sent to the Sunbury American, Corporal Henry Wharton wrote, “This victory was, to us, of company C, dearly brought, and will bring with it sorrow to more than one Sunbury.”

Soldiering On

Ordered to move from their encampment near Cedar Creek, Private David Sloan and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched to Camp Russell, a newly-erected, temporary Union Army installation that was located south of Winchester, just west of Stephens City, on grounds that were adjacent to the Opequon Creek. Housed here from November through 20 December 1864, they remained attached to the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah.

It was during this phase of service that Private Sloan was promoted to the rank of corporal—on 1 December 1864. Five days before Christmas, he and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians were on the move again—this time, marching through a snowstorm to reach Camp Fairview, which was located just outside of Charlestown, West Virginia. Following their arrival, they were assigned to guard and outpost duties.

1865 – 1866

Stationed at Camp Fairview from late December 1864 through early April 1865, Corporal David Sloan and other members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry continued to help fulfill the directive of Major-General Sheridan that the Army of the Shenandoah search out and eliminate the ongoing threat posed by Confederate States guerrilla soldiers who had been attacking federal troops, railroad systems and supply lines throughout Virginia and West Virginia.

This was not “easy duty” as some historians and Civil War enthusiasts have claimed but critically important because it kept vital supply lines open for the Union Army, as a whole, as it battled to finally bring the American Civil War to a close with the surrender of General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army at Appomattox Court House on 9 April 1865. In point of fact, it proved to be a dangerous time for the regiment, as evidenced by regimental casualty reports, which noted that several members of the 47th Pennsylvania were wounded or killed by Confederate guerrillas.

Assigned in February 1865 to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade, Army of the Shenandoah, the regiment was in an “improved condition and general good health,” according to a report penned at the end of that month by Regimental Chaplain William DeWitt Clinton Rodrock to his superiors.

A large influx of recruits has materially increased our numbers; making our present aggregate 954 men, including 35 commissioned officers.

The number of sick in the Reg. is 22; all of which are transient cases, and no deaths have occurred during the month.

Whilst in a moral and religious point of view there is still a wide margin for amendment and improvement; it is nevertheless gratifying to state that all practicable and available means are employed for the promotion of the spiritual and physical welfare of the command.

The next month, Chaplain Rodrock described the regiment’s condition as “favorable and improved,” adding:

In a military sense it has greatly improved in efficiency and strength. By daily drill and a constant accession of recruits, these desirable objects have been attained. The entire strength of the Reg. rank and file is now 1019 men.

Its sanitary condition is all that can be desired. But 26 are on the sick list, and these are only transient cases. We have now our full number of Surgeons, – all efficient and faithful officers.

We have lost none by natural death. Two of our men were wounded by guerillas, while on duty at their Post. From the effects of which one died on the same day of the sad occurrence. He was buried yesterday with appropriate ceremonies. All honor to the heroic dead.

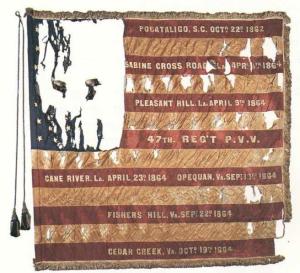

Sometime around this period, C Company Captain Daniel Oyster was authorized to take furlough; taking time out from visiting his family in Sunbury, he picked up the regiment’s Second State Colors—a replacement for the regiment’s very tattered, original battle flag. He later presented it to the regiment when he returned to duty.

Another New Mission, Another March

According to The Lehigh Register, as the end of March 1865 loomed, “The command was ordered to proceed up the valley to intercept the enemy’s troops, should any succeed in making their escape in that direction.” By 4 April 1865, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had made their way back to Winchester, Virginia and were headed for Kernstown. Five days later, they received word that Lee surrendered the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia to Union General Ulysses S. Grant.

In a letter penned to the Sunbury American on 12 April 1864, 47th Pennsylvanian Henry Wharton, described the celebration that took place, adding that Union Army operations in Virginia were still continuing in order to ensure that the Confederate surrender would hold:

Letter from the Sunbury Guards

CAMP NEAR SUMMIT POINT, Va.,

April 12, 1865Since yesterday a week we have been on the move, going as far as three miles beyond Winchester. There we halted for three days, waiting for the return or news from Torbett’s cavalry who had gone on a reconnoisance [sic] up to the valley. They returned, reporting they were as far up as Mt. Jackson, some sixty miles, and found nary an armed reb. The reason of our move was to be ready in case Lee moved against us, or to march on Lynchburg, if Lee reached that point, so that we could aid in surrounding him and [his] army, and with Sheridan and Mead capture the whole party. Grant’s gallant boys saved us that march and bagged the whole crowd. Last Sunday night our camp was aroused by the loud road of artillery. Hearing so much good news of late, I stuck to my blanket, not caring to get up, for I suspected a salute, which it really was for the ‘unconditional surrender of Lee.’ The boys got wild over the news, shouting till they were hoarse, the loud huzzas [sic] echoing through the Valley, songs of ‘rally round the flag,’ &c., were sung, and above the noise of the ‘cannons opening roar,’ and confusion of camp, could be heard ‘Hail Columbia’ and Yankee Doodle played by our band. Other bands took it up and soon the whole army let loose, making ‘confusion worse confounded.’

The next morning we packed up, struck tents, marched away, and now we are within a short distance of our old quarters. – The war is about played out, and peace is clearly seen through the bright cloud that has taken the place of those that darkened the sky for the last four years. The question now with us is whether the veterans after Old Abe has matters fixed to his satisfaction, will have to stay ‘till the expiration of the three years, or be discharged as per agreement, at the ‘end of the war.’ If we are not discharged when hostilities cease, great injustice will be done.

The members of Co. ‘C,’ wishing to do honor to Lieut. C. S. Beard, and show their appreciation of him as an officer and gentleman, presented him with a splendid sword, sash and belt. Lieut. Beard rose from the ranks, and as one of their number, the boys gave him this token of esteem.

A few nights ago, an aid [sic] on Gen. Torbett’s staff, with two more officers, attempted to pass a safe guard stationed at a house near Winchester. The guard halted the party, they rushed on, paying no attention to the challenge, when the sentinel charged bayonet, running the sharp steel through the abdomen of the aid [sic], wounding him so severely that he died in an hour. The guard did his duty as he was there for the protection of the inmates and their property, with instruction to let no one enter.

The boys are all well, and jubilant over the victories of Grant, and their own little Sheridan, and feel as though they would soon return to meet the loved ones at home, and receive a kind greeting from old friends, and do you believe me to be

Yours Fraternally,

H. D. W.

Two days later, that fragile peace was shattered when a Confederate loyalist fired the bullet that ended the life of President Abraham Lincoln.

On 16 April 1865, U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and Lieutenant-General Ulysses S. Grant issued General Orders, No. 66, confirming that President Abraham Lincoln had been murdered and informing all Union Army regiments about changes to their duties, effective immediately, in the wake of President Lincoln’s assassination. Those orders also explained to Union soldiers what the appropriate procedures were for mourning the president:

The distressing duty has devolved upon the Secretary of War to announce to the armies of the United States, that at twenty-two minutes after 7 o’clock, on the morning of Saturday, the 15th day of April, 1865, ABRAHAM LINCOLN, President of the United States, died of a mortal wound inflicted upon him by an assassin….

The Headquarters of every Department, Post, Station, Fort, and Arsenal will be draped in mourning for thirty days, and appropriate funeral honors will be paid by every Army, and in every Department, and at every Military Post, and at the Military Academy at West Point, to the memory of the late illustrious Chief Magistrate of the Nation and Commander-in-Chief of its Armies.

Lieutenant-General Grant will give the necessary instructions for carrying this order into effect….

On the day after the receipt of this order at the Headquarters of each Military Division, Department, Army, Post, Station, Fort, and Arsenal and at the Military Academy at West Point the troops and cadets will be paraded at 10 o’clock a. m. and the order read to them, after which all labors and operations for the day will cease and be suspended as far as practicable in a state of war.

The national flag will be displayed at half-staff.

At dawn of day thirteen guns will be fired, and afterwards at intervals of thirty minutes between the rising and setting sun a single gun, and at the close of the day a national salute of thirty-six guns.

The officers of the Armies of the United States will wear the badge of mourning on the left arm and on their swords and the colors of their commands and regiments will be put in mourning for the period of six months.

Matthew Brady’s photograph of spectators massing for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, at the side of the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half-mast following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Reassigned to defend the nation’s capital, Corporal David Sloan and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were stationed just outside of Washington, D.C., prepared to intercept any former Confederate soldiers or their sympathizing followers bent on wreaking more havoc in the nation’s capital.

Prohibited from attending President Lincoln’s funeral in Washington, D.C., because they were expected to remain on duty, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers joined with other Union troops in mourning him during a special, separate memorial service conducted for their brigade that same day. Officiated by the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Chaplain, the service enabled the men to voice their grief at losing their beloved former leader. Chaplain Rodrock later expressed the feelings of many 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers as he described Lincoln’s assassination as “a crime against God, against the Nation, against humanity and against liberty” and “the madness of Treason and murder!” Written as part of a report to his superiors on 30 April 1865, he added, “We have great duties in this crisis. And the first is to forget selfishness and passion and party, and look to the salvation of the Country.”

Letters penned by other 47th Pennsylvanians to family and friends back home during this period documented that C Company Drummer Samuel Hunter Pyers was given the honor of guarding the late president’s funeral train while other members of the regiment were involved in guarding the key conspirators in Lincoln’s assassination during the early days of their confinement at the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C.

It was also during this phase of duty that C Company Private William Michael, Corporal David Sloan’s friend and brother-in-law, was honorably discharged. Given advanced medical treatment at the U.S. General Hospital at the Summitt House in Philadelphia after being wounded during the Battle of Cedar Creek in October 1864, he had continued to convalesce there until he was released from active service on 20 May 1865, per General Orders, No. 77, which had been issued by the U.S. Office of the Adjutant General earlier that year, and subsequently returned home.

On 11 May 1865, the 47th Pennsylvania’s First State Color was retired and replaced with the regiment’s Second State Color. Attached to Dwight’s Division, 2nd Brigade, U.S. Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers next flexed their muscles in an impressive show of the Union Army’s power and indomitable spirit during the Union’s Grand Review of the Armies, which was conducted in Washington, D.C. from 23-24 May 1865, under the watchful eyes of President Lincoln’s successor, President Andrew Johnson, and Lieutenant-General Grant.

Reconstruction Duties

Ruins of Charleston, South Carolina as seen from the Circular Church, 1865 (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

Assigned to Provost (military police) and Reconstruction-related duties during their final phase of military service, Corporal David Sloan and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were sent on a final swing through America’s Deep South. Still attached to Dwight’s Division, they were initially stationed in Savannah, Georgia from 31 May to 4 June 1865, as part of the 3rd Brigade of the U.S. Army’s Department of the South.

Ordered to relieve the 165th New York Volunteers in July, they quartered in the former mansion of the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury in Charleston, South Carolina. Assigned to provost duty, they ensured the smooth operation of the local judicial system by providing guards for the area’s jails, facilitating operations of the courts and carrying out other civic governance tasks as needed.

Finally, on Christmas Day, 1865, the majority of the regiment mustered out for the final time at Charleston, South Carolina. Following a voyage home to New York by ship, the weary 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers were transported to Camp Cadwalader in Philadelphia, where they received their honorable discharge papers in early January 1866.

Promised a bounty of two hundred and twelve dollars when he enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania, Corporal David Sloan was still owed one hundred and ninety dollars of that bounty at the time of his final discharge, and was informed that he still personally owed the regiment’s sutler three dollars for clothing and other supplies. Astoundingly, he was also advised that he was expected to pay the federal government back for six dollars’ worth of “Arms and Accoutrements.”

Return to Civilian Life

Elkton, Maryland retained its rural appeal well into the 1900s, as evidenced by this view of the Partridge Hill area (public domain).

Following his honorable discharge from the military, David Sloan resumed work as a stone cutter. Still involved with community fire prevention activities, he also became an active member of the Veteran Firemen’s Association of Philadelphia.

Sometime in 1867, David Sloan relocated with his wife and son, Joseph, to Elkton, Maryland, where David then founded the Elkton Marble Works. Together, they welcomed the birth of two more children: Elizabeth Jane Sloan (1867-1921), who was born in October 1867 and later wed John R. Lewis (1864-1930); and James Elmer Sloan (1875-1931), who was born on 2 August 1875, was known to family and friends as “Elmer,” and who later wed Sarah Whitlock.

Over time, the Elkton Marble Works became a father-and-son concern, as David Sloan’s son, Joseph, became increasingly active in its operation. Together, they eventually operated the company that came to be known as D. L. Sloan & Son and were both respected as craftsmen of the marble and other stonework utilized in cemetery memorials and mausoleums across the region.

An active member of the Grand Army of the Republic, David L. Sloan was a frequent attendee at local chapter events at the Wingate Post in Maryland, as well as national G.A.R. conventions. He also continued to pursue his avid interests in the field of community fire protection. A member of the Volunteer Firemen’s Association, he became one of the co-founders of Elkton’s Singerly Steam Fire Engine and Hook and Ladder Company, serving as the fire company’s chief and as a member of its board of directors.

As with many of his fellow members of the 47th Pennsylvania, David Livingston Sloan’s health began to fail while he was still in his sixties. Diagnosed with heart disease, he fell ill during the winter of 1900—a condition which quickly worsened. On 12 February of that year, The Baltimore Sun reported that he was “dangerously ill with pneumonia.”

Death and Interment

The ink of that troubling newspaper edition had barely had time to dry before another edition of The Baltimore Sun was carrying the grave news that David L. Sloan had succumbed to pneumonia at the age of sixty-five. Following his passing at his home on Stockton Street in Elkton, Maryland on 13 February 1900, and funeral services that were conducted there by the Rev. T. E. Terry of the Elkton Methodist Episcopal Church before a large assembly of mourners on 16 February, he was interred at that city’s Elkton Cemetery with military honors. Pallbearers included members of the Grand Army of the Republic’s Wingate Post, the Volunteer Firemen’s Association, the Veteran Firemen’s Association of Philadelphia, and his brother firemen from Elkton’s Singerly Fire Company.

According to The Cecil Whig and the long-running Baltimore Sun:

David L. Sloan, senior member of the firm of D. L. Sloan & Son, marble cutters, died at his home on Stockton street, Elkton, this morning after several weeks’ illness, aged 65 years. He came to Elkton 33 years ago.

He was born in Philadelphia on August 4, 1833, and early in life connected himself with the Volunteer Fireman Association of Philadelphia, of which he continued a member until his death. He enlisted in Company A, Forty-seventh Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers, at the outbreak of the Civil War and served until its close. He was a member of Wingate Post No. 9, G. A. R., North East. Mr. Sloan was one of the original incorporators of the Singerly Fire Company of Elkton.

A widow and three children survive him—Joseph H. and J. E. Sloan and Mrs. J. R. Lewis, of Philadelphia.

Three months later, on 15 May 1900, his former comrades of the 127th Pennsylvania paid tribute to him as they “called the roll of honor of those who passed to the Great Beyond since last year’s reunion” during their annual meeting in Steelton, Pennsylvania.

What Happened to the Wife and Children of Corporal David Livingston Sloan?

David L. Sloan’s widow, Johanna (Michael) Sloan, survived him by just over a year, passing away in Elkton on 6 August 1901. Following funeral services, she was laid to rest beside him at the Elkton Cemetery. David L. Sloan’s children, Joseph Hooker Sloan, Elizabeth Jane (Sloan) Lewis and James Elmer Sloan, all went on to live productive lives.

- Joseph Hooker Sloan (1864-1947) wed Cornelia Elizabeth Chick in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on 28 December 1887. A Maryland native, she was a daughter of Joseph Chick of Elkton and had been born on 11 June 1862. Together, they welcomed the birth of their first child, J. Raymond Sloan (1889-1890), on 6 January 1889. Sadly, he did not survive infancy, passing away on 27 March 1890. Their second son, however, left a longer-lasting mark on the world. Named after Corporal David Livingston Sloan (1835-1900), the American Civil War veteran who had served with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, David Livingston Sloan (1891-1977) was born in Elkton, Maryland on 31 July 1891, and later wed and raised a family with Elizabeth V. Perkins (1893-1970).The third child of Joseph and Cornelia Sloan, Earle S. Sloan (1895-1895), also did not survive infancy. Born on 30 June 1895, he died on 14 August of that same year. Their fourth child, Cornelia Sloan, escaped a similar fate, however; born in 1920, she was documented as still residing with her parents, Joseph Hooker Sloan and Cornelia (Chick) Sloan, in Elkton in 1920, and as having adopted the married surname of Weldin sometime prior to the 1971 death of her father’s second wife, Lula B. Sloan (according to Lula’s obituary).Having assumed management responsibilities of D. L. Sloan & Co., following his own father’s death in February 1900, Joseph Hooker Sloan had gone on to have his own successful business career. A participant in the commissioning ceremonies of the battleship USS Alabama in Delaware on 13 October 1900, he was involved in creating the Elkton Doughboy Monument in Elkton, Maryland to honor men who had died in service to the nation during World War I, and had continued to grow his family’s business, the Elkton Marble and Granite Works, well into the 1940s.Predeceased by his ailing wife, Cornelia E. (Chick) Sloan (1862-1920), who had passed away at the age of sixty in Elkton on 12 June 1920, he had remarried sometime before 1930, when a federal census enumerator documented that he and his wife, Lula B., were residing together in Elkton. His second wife, Lula E. (Bailey) Barwick (1876-1971), had been widowed by John Seward Barwick (1874-1919) in 1919.A treasurer of his local Methodist church for thirty-five years, Joseph Hooker Sloan was also a “grand keeper of the wampum of the Maryland Grand Lodge, Improved Order or Redmen,” according to his obituary, as well as a member of the multiple other civic and social organizations, including the Elkton Lodge of Odd Fellows and the Elkton Rotary. Ailing for the final year of his life, he passed away at his home in Elkton on 26 November 1947, and was interred at the same cemetery where his Civil War soldier-father had been laid to rest—the Elkton Cemetery in Elkton, Maryland.His second wife, Lula E. (Bailey Barwick) Sloan, survived him by roughly a quarter of a century, passing away at the age of ninety-five at the Union Hospital in Elkton on 23 December 1971. She was subsequently laid to rest next to her first husband, John Seward Barwick, at the Sudlersville Cemetery in Sudlersville, Maryland.

- Elizabeth Jane Sloan (1867-1921), the second child of American Civil War veteran David Livingston Sloan, wed John R. Lewis (1864-1930) in Elkton on 12 December 1891. Together, they welcomed the births of: Robert Melvin Lewis (1892-1954), who was born in Philadelphia on 8 September 1892); Carroll Calvert Lewis (1894-1894), who was born in Philadelphia on 4 December 1894) and died in El Monte, California on 20 November 1980; Caroline Bell Clement Lewis (1895-1978), who was born in Philadelphia on 22 March 1895); and Thomas C. Lewis (1905-1994), who was born in Springfield, Delaware County, Pennsylvania on 9 April 1905. Her husband supported their family on his wages as a fireman and, later, as a railroad worker.After roughly three decades of marriage, Elizabeth Jane (Sloan) Lewis passed away at the age of fifty-four in Pennsylvania on 15 July 1921, and was interred at the Arlington Cemetery in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania.

- James Elmer Sloan (1875-1931), the third child of Civil War veteran David Livingston Sloan, was known to family and friends as “Elmer.” After marrying Sarah Whitlock in Philadelphia on 23 January 1901, they welcomed the births of: Esther May Sloan (1905-1977), who was born in Pennsylvania on 30 May 1905 and died in Maryland, at the age of seventy-two, on 16 October 1977; and Mary Ellen Sloan (1916-1916), who died in infancy in Collingswood, Camden County, New Jersey on 16 February 1916.Elmer Sloan preceded his wife in death, when he passed away at the age of fifty-six, in Sparrows Point, Baltimore County, Maryland. Like his father before him, he was interred at the Elkton Cemetery. His widow, Sarah (Whitlock) Sloan died in Maryland on 13 October 1968.

Descendants and Subsequent Namesakes of Corporal David Livingston Sloan

Corporal David Livingston Sloan’s name continued to live on, long after his passing at the dawn of the twentieth century. His grandson, David Livingston Sloan (1891-1977), was born in Elkton, Maryland on 31 July 1891 as the first surviving child of Joseph Hooker Sloan (1864-1947), and would later become known as “David L. Sloan, Sr.” before ultimately becoming known as “David L. Sloan, I.”

That path as a family patriarch began when David L. Sloan wed Elizabeth Virginia Perkins (1893-1970) sometime between 1910 and the birth of their son, David Livingston Sloan, Jr. (1916-2002), in Elkton on 20 September 1916. In 1920, the trio resided in Philadelphia’s 34th Ward. At that time, David Livingstone, Sr. (1891-1977; later David L. Sloan, I) was employed as a civil engineer for a railroad company. By 1930, they were residing in Wynnewood, Lower Merion Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, and David Sloan, Sr. was operating his own construction company.

Still operating that construction company by 1940, he and his wife, Elizabeth, were residing alone in Narberth, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. She predeceased him, passing away in the town of Wayne in Delaware County, Pennsylvania on 5 December 1970. Nearly seven years to the day later, he followed her in death when he passed away in Wayne on 3 December 1977. He was laid to rest beside her at the Elkton Cemetery.

Their son, David L. Sloan, Jr. (1916-2002), who was the great-grandson of Civil War veteran David L. Sloan (1835-1900), went on to graduate from Lower Merion High School, attend Drexel University and the University of Delaware, and marry fellow University of Delaware student Mary Louise Steel at St. John’s Roman Catholic Church in Newark, New Castle County, Delaware, on 1 July 1938. Making his home with her in 1940 in Philadelphia, he was employed as a laboratory technician for the Charles E. Hire Company, a manufacturer of soft drink products, and later became that company’s director of quality control, as well as the proprietor of Corner Cupboard Antiques, a small business that he founded in 1961. His wife was a daughter of Dr. Walter Hossinger Steele, a native of Maryland, and Catherine/Kathryn (Pie) Steel, a native of Pennsylvania. Their children were: David Livingston Sloan, III, who was born in Pennsylvania in October 1940 and later resided in Richardson, Texas and Fort Lauderdale, Florida; Kathryn Elizabeth Sloan, who was born in Pennsylvania in August 1943, was and known to family and friends as “Kathy,” and was commissioned as an officer in the United States Naval Reserve during the 1960s, and later resided in Kimberton and Phoenixville, Pennsylvania; and Karen Sloan, who was born in Pennsylvania in December 1945 and later wed and resided with Bill Flagg in Warren Point, Warwick Township, Pennsylvania.

David L. Sloan, Jr. (or “David L. Sloan, II”) divided his time in later years between Kimberton, Pennsylvania and Harbor Cove, North Port, Florida. He died at the age of eighty-five at the Phoenixville Hospital on Friday morning, 15 March 2002. Following a funeral mass at St. John’s Roman Catholic Church in Newark, he was laid to rest at that church’s cemetery. His widow, Louise (Steel) Sloan followed him in death roughly eight years later, passing away in her early nineties in 2010.

Their son, David Livingston Sloan, III (born circa 1941), graduated from Villanova University and wed Eileene Theresa Chadwick, a daughter of William Gregory Chadwick of Philadelphia, at the Old St. Mary’s Church on 26 August 1967. They subsequently welcomed the birth of son David Livingston Sloan, IV, who spent many of his formative years near Dallas, Texas, attended Florida International University and pursued a career in the tourism industry before becoming a successful author in Key West, Florida and a generous supporter of multiple civic and educational programs across the United States.

Sources:

- Alleman, H.C., F. Asbury Awl, et. al. History of the 127th Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers. Lebanon, Pennsylvania: Press of Report Publishing Company, 1902.

- Bates, Samuel. P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- “Camp Russell.” The Historical Marker Database, retrieved online December 27, 2023.

- “Civil War, 1861-1865.” Stephens City, Virginia: Newtown History Center, retrieved online December 27, 2023.

- “David L. Sloan” (mention of his illness from pneumonia), in “Burglar Sentenced.” Baltimore, Maryland: The Baltimore Sun, 12 February 1900, p. 7.

- “David L. Sloan” (obituary). Baltimore, Maryland: The Baltimore Sun, 14 February 1900, p. 7.